Читать книгу Impressionism - Nathalia Brodskaya - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

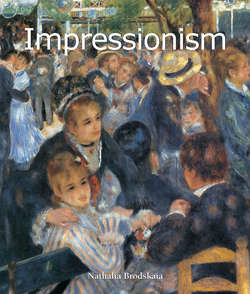

The Impressionists and Academic Painting

Оглавление2. Pierre Auguste Renoir, Nude, 1876.

Oil on canvas, 92 × 73 cm.

The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

3. Edgar Degas, Woman Combing her Hair, c.1888–1890.

Pastel on paper, 78.7 × 66 cm.

Mr. and Mrs. A. Alfred Taubman Collection.

The young men who would become the Impressionists formed a group in the early 1860s. Claude Monet, son of a Le Havre shopkeeper, Frédéric Bazille, son of a wealthy Montpellier family, Alfred Sisley, son of an English family living in France, and Pierre Auguste Renoir, son of a Parisian tailor had all come to study painting in the independent studio of Charles Gleyre, whom in their view was the only teacher who truly personified neo-classical painting.

The formal qualities of his female nudes can only be compared to the work of the great Dominique Ingres. In Gleyre’s independent studio, pupils received traditional training in neo-classical painting, but were free from the official requirements of the École des beaux-arts.

All four artists burned with desire to grasp the principles of painting and neo-classical technique: after all, this was the reason that they had come to Gleyre’s studio. They applied themselves to the study of the nude figure and successfully passed all their required exam competitions, receiving prizes for drawing, perspective, anatomy, and likeness. Each of the future Impressionists received Gleyre’s praise on some occasion.

One day Renoir decided to impress his teacher by painting a nude according to all the rules, as he put it: “tan flesh emerging from bitumen black as night, backlighting caressing the shoulder, and the tortured look that accompanies stomach cramps.” (Jean Renoir, Pierre Auguste Renoir, mon père, Paris, Gallimard, 1981, p. 119). Gleyre was struck by Renoir’s impertinence and his shock and indignation were not unwarranted: his student had proved that he was perfectly capable of painting as the teacher required, whereas all the other youths were bent on depicting their models “as they are in everyday life” (J. Renoir, op. cit., p. 120). Monet remembers the way Gleyre reacted to one of his own nudes: “Not bad,” he exclaimed, “not bad at all, this business here. But it is too much about this particular model. You have a heavyset man. He has huge feet, which you depict as such. It’s all very ugly. So remember young man, when we draw a figure, we must always keep in mind the antique. Nature, my friend, is a very admirable aspect of research, but it provides no interest.” (François Daulte, Frédéric Bazille et son temps, Geneva, Pierre Cailler, 1952, p. 30).

To the future Impressionists, nature was exactly what interested them most. Renoir remembered what Frédéric Bazille had told him when they first met: “Large-scale classical compositions are over. The spectacle of everyday life is more fascinating.” (J. Renoir, op. cit., p. 115). All of them preferred living nature and bristled at Gleyre’s disdain for landscape. But in reality the students enjoyed complete freedom. They were acquiring indispensable knowledge of the technique and craft of painting, mastery of classical composition, precision in drawing, and beautiful paint handling, although later critics often rightly noted their lack of such achievements.

4. Alfred Sisley, Avenue of Chestnut Trees at La Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1867.

Oil on canvas, 95.5 × 122.2 cm.

Southampton City Art Gallery, Southampton.

On their way home from Gleyre’s studio, Bazille, Monet, Sisley and Renoir stopped at the Closerie des Lilas, a café on the corner of boulevard Montparnasse and avenue de l’Observatoire, where they had long discussions about the future direction of painting. Bazille brought along his new friend, Camille Pissarro, who was a few years older than the others. The members of this small group called themselves the “intransigents” and together they dreamt of a new Renaissance.

Many years later, the elder Renoir spoke enthusiastically about this period to his son. “The intransigents wanted to put their immediate impressions on canvas, without any translation,” writes Jean Renoir. “Official painting, imitating imitations of the masters, was dead. Renoir and his companions were bon vivants… Meetings of the intransigents were impassioned. They longed to share their discovery of the truth with the public. Ideas came from all sides and intermingled; opinions came thick and fast. One of them seriously suggested burning down the Louvre.” (J. Renoir, op. cit., p. 120–121). Sisley apparently was the first to take his friends landscape painting in Fontainebleau forest.

5. Camille Pissarro, Edge of the Woods near L’Hermitage, 1879.

Oil on canvas, 125 × 163 cm.

Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland.

Now, instead of a model skilfully placed upon a pedestal, they had nature before them and the infinite variations of the shimmering foliage of trees constantly changing colour in the sunlight. “Our discovery of nature opened our eyes,” said Renoir. (J. Renoir, op. cit., p. 118). No doubt an equally important influence on their passion for nature was the public exhibition that same year (1863) of Édouard Manet’s painting Luncheon on the Grass. The painting astonished the future Impressionists, as well as critics and observers. Manet had begun to accomplish what they dreamt of: he had taken the first steps away from neo-classical painting and moved closer to modern life. Truth be told, “burning down the Louvre” was little more than a spontaneous expression bandied about in the heat of discussion, not a conviction. When asked if he had got anything out of Gleyre’s neo-classical studio, the elder Renoir replied to his son: “A lot, in spite of the teachers. Having to copy the same écorché (anatomical study) ten times is excellent. It’s boring, and if you weren’t paying for it, you wouldn’t be doing it. But to really learn, nothing beats the Louvre.” (J. Renoir, op. cit., p. 112–113).