Читать книгу Surrealism - Nathalia Brodskaya - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

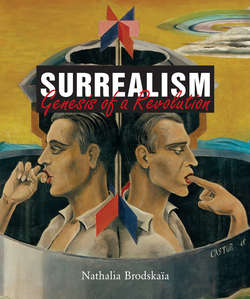

Surrealism

Dada in Paris

ОглавлениеThe beginnings of Surrealism within Dada are connected, in the first instance, to poetry rather than to the visual arts. At the centre, as the symbol that united the Dadaist poets, was Guillaume Apollinaire. After he left the hospital, Apollinaire saw his disciples every Tuesday at gatherings at the Café de Flore on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. Earlier on, he had met the young poet André Breton who had visited him in the hospital in 1916, immediately after the trepanation of his skull.

André Breton himself contained all the immense energy which led to the emergence of Surrealism. He was born in 1896 in the little town of Tinchenbray, in Normandy in the north of France. His parents strove to give their only son a good education. In 1913, he began to study medicine in Paris, and was preparing for a future as a psychiatrist. The war got in the way. Breton was drafted into the artillery, but, as a future doctor, he was ordered to serve as a medic. In the Val-de-Grace hospital, he encountered another medical student and poet, Louis Aragon.

Aragon, the illegitimate son of a prefect of police, was born in 1897 in Paris. He was a refined, slim and delicate young man who admired Stendhal and had studied at the Sorbonne. The companions of his youth never doubted that he was going to be a poet. During the war, he twice obtained a deferment, but doctors were needed at the front and Aragon was sent into the rapid training programme for “doctor’s assistants” at Val-de-Grace. After this he went to the front, where he acted heroically. Breton even criticised him for his excessive selflessness and patriotism: “Nothing in him at that moment rose up in revolt. He had been teasing us in some ways with his ambition to overthrow absolutely everything, but when it came down to it, he conscientiously obeyed every military order and fulfilled all his professional (medical) obligations.”[29] His military experience, without a doubt, played a big role in his Dadaist and Surrealist poetry.

Federico Castellon, Untitled (Horse), c. 1938.

Oil on board, 37.2 × 32.4 cm.

Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York.

Leonora Carrington, The Inn of the Dawn Horse, 1937–1938.

Private Collection.

It looked as though a medical future also awaited a third poet, a man of the same age, Philippe Soupault. He came from the family of a famous doctor, and studied jurisprudence, but his greatest enthusiasm was poetry. In 1914, while in London, he wrote his first notable poem: “Chanson du mal aimé”. In 1916, he obtained a deferment, but was then drafted into the artillery and sent to officers’ school, though he never actually got to the front. Soupault spent many weeks in hospital after the officers had been given an anti-typhoid serum in an experiment. There he wrote poems which he sent to Apollinaire. In 1917, Apollinaire published a poem of Soupault’s in the journal SIC, and introduced him to Breton and Aragon. None of them was thinking about medicine any more. The three poets planned to found a literary journal.

The journal Littérature came out in February 1919, taking over from SIC and Nord-Sud. Many in the world of letters hailed the birth of the journal, including Marcel Proust. As well as their own poems, the three printed those of Apollinaire, Isidore Ducasse, Rimbaud and the Zürich Dadaist Tzara. An unknown serviceman, Paul Éluard, submitted a poem to the journal. His real name was Eugène Grendel, but he used his maternal grandmother’s surname, Éluard, as a pseudonym. After he left school, he contracted tuberculosis and spent two years in Switzerland in a sanatorium. In Davos, Éluard met a Russian girl, Elena Diakonova, whom he married in 1917. Elena entered the world of the Dadaists, and later, by which time she was known as Gala, “the muse of the Surrealists. “At the front, Éluard was exposed to German poison gas, and, following a period in the hospital, he made his way to Paris.

Later, after he arrived in Paris, Picabia joined the group, followed by Duchamp as well. In the spring of 1919, Littérature published the first chapters of a work by Soupault and Breton entitled “Magnetic Fields”. They wrote these pieces together, and one can only guess at the authorship of the individual poems. Soupault later stated that in the course of his experiments, he had tried using “automatic writing” – a method which makes it possible to become liberated from the weight of criticism and the habits formed at school, and which generates images as opposed to logical calculations:

Trace smell of sulphur

Marsh of public health

Red of criminal lips

Walk twice brine

Whim of monkeys

Clock colour of day.[30]

Breton wrote that the “Magnetic Fields” constituted the first Surrealist, as opposed to Dadaist, work, although Surrealism was destined to appear officially only in 1924. Granted, one can find there much evidence of the influence of the French Symbolists and Lautréamont. Granted, the nihilist character of Dada is still present. However, the poems of Soupault and Breton did not make a complete break, either with logic, romanticism, or reflection on aspects of real life and modern times. A new style of literature and fine art was prefigured in the combination of all these qualities.

Opening of sorrows one two one two

These are toads the red flags

The saliva of the flowers

The electrolysis of the beautiful dawn

Balloon of the smoke of the suburbs

The clods of earth cone of sand

Dear child whom they tolerate you are getting your breath back

Never pursued the mauve light of the brothels…[31]

James Guy, Venus on Sixth Avenue, 1937.

Oil on paperboard, 59.7 × 74.9 cm.

Columbus Museum, Columbus.

The appearance of Tzara in the home of Francis Picabia in Paris coincided with the start of an event staged by the Parisian Dadaists. Tzara’s experience of work in the Cabaret Voltaire instilled new energy into the plans of Breton and Soupault’s set. The first evening took place on January 23, 1920, in the hall of the Palais des Fêtes at the Porte Saint-Martin. The show included a reading by Breton of poems about artists, and a display of paintings by Léger, Gris and de Chirico. When Picabia’s pictures were shown to the public, their obscene content provoked a storm of indignation. The audience left the hall, and the organisers felt that Dadaist art had brought them closer together. They were very young, they regarded the audience with contempt, and they were openly aiming to destroy the rules and norms that had been inherited from the past. They usually got together at the home of Picabia, where they discussed their plans.

The second public event took place in the Grand Palais on February 5. Tzara published a provocative announcement in the newspapers that Charlie Chaplin was going to be present, and this brought in the crowds. The Dadaist manifestos also sounded provocative when they were read aloud. “The audience reacted with fury”, Ribemont-Dessaignes later recalled. “The organisers of the evening had achieved their main objective. It was essential to incite hostility, even at the risk of being taken for utter fools.”[32] Someone accused them of promoting German propaganda. All the same, the owner of the Club du Faubourg in the Paris suburb of Puteaux offered the Dadaists his hall for the next event, which took place two days later on February 7. A naughty speech by Aragon incited a squabble between the anarchists and the socialists, which was brought to an end by Breton’s reading of Tristan Tzara’s “Dada Manifesto 1918”. Afterwards a demonstration was held in the People’s University in the suburb of Saint-Antoine. The following evening, on March 27, there was a musical and theatrical event at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre. There, Breton read aloud Picabia’s “Cannibal Manifesto”, which was a parody of the kind of patriotic orations which were used to encourage audiences in the rear. Picabia once again offended bourgeois taste with his ensemble painting. A furry stuffed animal, an ape, was attached to the canvas, surrounded by Picabia’s: Portrait of Cezanne, Portrait of Rembrandt, Portrait of Renoir and Still Life.

Salvador Dalí, The Old Age of William Tell, 1931.

Oil on canvas, 98 × 140 cm.

Private Collection.

A Dada festival was held two months later, on May 26, 1920, in the spacious Salle Gaveau on the Rue La Boétie. It was their most sensational event in Paris. There were music and sketches, and plays by Breton and Soupault were staged. The unusual dynamism of Dada shows in 1920 attracted new and younger disciples to their ranks, among whom were the poets Robert Desnos and Benjamin Peret, and the artist Serge Charchoune. The last sensational performance of 1920 was held in December. Picabia once again organised a provocative exhibition, and Jean Cocteau led a jazz band in which random performers played on random instruments. Tzara read out his manifesto with the instructions on how to compose poems. In 1920, Marcel Duchamp, whose works were shown under the pseudonym of Rrose Sélavy (in French, sounds like “Eros, c’est la vie”, in English, “Eros is life”), exhibited his famous L. H. O.O.Q., one of his Ready-Mades – a reproduction of the Mona Lisa to which the artist had added a beard and a moustache in pencil. It contained all the Dadaist denial of the classics and all their contempt for art in general. However, the excessive strain, the incredible rhythm of the performances, and the clashes among the incompatible personalities called for a breathing-space in their activity.

The year 1921 was marked by a new outburst of Dadaist activity. The year started with the implementation of the “visits” project, conceived by Breton – a Dadaist parody of the traditional code of polite society in past times. However, the act near the church of Saint-Julien-le-pauvre virtually came to nothing on account of rain. Nor did the trial of the writer Maurice Barres have the success they expected of it. A tribunal chaired by Breton found him guilty of the nationalism and extremism of the war years. The song sung by Tristan Tzara, “Dada Song”, livened up the event.

The song of a Dadaist

Who had Dada at heart

Overtired his motor

Which had Dada at heart

The lift was carrying a king

Heavy fragile enormous

He cut off his big right arm

And sent it to the Pope in Rome

This is why

The lift

No longer had Dada at heart

Eat chocolate

Wash your brain

Dada

Dada

Drink water.[33]

Toyen (Marie Cermínová), The Sleeper, 1937.

Private Collection.

More interesting still, in the context of the gestation of Surrealism, was the exhibition of Max Ernst which opened on May 2. Until then, the main figure from the visual arts that had made an appearance under the aegis of Dada was Picabia. Around that time, he was distancing himself more and more from Breton and Aragon’s company. Ernst was invited, to a large extent, out of a desire to play a joke on Picabia. They rented the bookshop Sans Pareil on the Rue Kleber for the exhibition. The invitation – the so-called “Pink Prospectus” – was couched in a half-nonsensical, derisive tone: “Entry is free, hands in pockets. The exit is guarded, painting under the arm.”[34] Everybody who mattered attended the viewing. One of the Dadaists, who had hidden himself in a cupboard, shouted out absurd phrases from inside it, along with the names of famous people: “Attention. Here is Isadora Duncan”, “Louis Vauxcelle, André Gide, van Dongen.” As it happened, both Gide and van Dongen were among those who attended. The stage was in the basement, all the lights were turned out, and heart-rending cries could be heard coming from a trap-door. …Breton struck matches, Ribemont-Dessaignes repeatedly shouted out the phrase “It’s dripping onto the skull”, Aragon meowed, Soupault played hide-and-seek with Tzara, while Peret and Charchoune spent the whole time shaking hands. As always, poems were read.

Even Parisians who had seen many sights were surprised by the exhibition itself. Ernst showed the most varied pieces: there were “mechano-plastic” works inspired by mechanical forms, objects, painted canvasses and drawings. Ernst’s collages were fundamentally different from the collages in which the Cubists had already given lessons – they had a poetic quality and provoked numerous associations. Ernst gave inexplicable titles to his works – for example, the Little Eskimo Venus, The Slightly Ill Horse, Dada Degas – and accompanied them with “verbal collages”. His poems were close in spirit to those of Breton’s circle. Indeed, it was after this exhibition of Max Ernst that Breton worked out a few fundamental principles of Surrealism for his later manifesto.

Yves Tanguy, Landscape with Red Cloud, 1928.

Private Collection.

Roland Penrose, Seeing is believing, 1937.

Oil on canvas, 100 × 75 cm.

The Roland Penrose Collection, Sussex.

The next exhibition was that of the Salon Dada which opened on June 6, 1921 on the Champs-Elysees, and lasted until June 18, extending over all the evenings which entered into the Salon Dada programme. In the exhibition hall, a very wide range of objects hung from the ceiling: an opened umbrella, a soft hat, a smoker’s pipe, and a cello wearing a white tie. Since the exhibition was advertised as an international one, invitations were sent out to Arp in Switzerland, Ernst and Baargeld in Germany, Man Ray in America, as well as other artists. Ernst exhibited his Cereal Bicycle with Bells for the first time. One picture by Benjamin Peret showed a nutcracker and a rubber pipe, and it was called The Beautiful Death, while another showed the Venus de Milo with a man’s shaven head. Under a mirror belonging to Philippe Soupault and reflecting the visitor’s own face was the inscription: Portrait of an Unknown Figure. Other works by Soupault were titled The Garden of My Hat, Sympathy with Oxygen, and Bonjour, Monsieur. In addition to all the other absurd inscriptions, a placard hung in the lift-cage which read “Dada is the biggest swindle of the century”. This exhibition already clearly pointed to Surrealism.

Despite the very serious contradictions between the strong individual personalities in the Dadaist movement, Breton designed one further “big swindle” in 1922. The Dadaists decided to hold their own Paris Congress – “The International Congress for the Determination of Directives and the Defence of the Modern Mind”. Despite almost six months of preparation, a wealth of publications, and a lively correspondence between Tzara, Picabia, Breton and others, this plan experienced a setback. André Breton was forced to admit that the movement was already dead and buried, and that there was no point in trying to resurrect it. However, just at that moment, in the spring of 1922, an event took place heralding the birth of Surrealism from within the Dadaist movement. A new number of Littérature, a journal which had not come out for some time, appeared on March 1, 1922. In it were published Breton’s “Three Tales of Dreams”, and his article entitled “Interview with Professor Freud in Vienna”. In 1921, at the time of his visit to Vienna, Breton failed to get an interview with Freud, but both publications testified to the author’s interest in using psychoanalysis for the expression of the unconscious in art. From the fourth number of the journal onwards, Breton took the entire management of the journal on himself. Appealing to those who remained in his camp, Picabia, Duchamp, Picasso, Aragon and Soupault, Breton wrote: “It cannot be said that Dadaism served any purpose other than to support us in a state of lofty emancipation, which we now reject, being of sound mind and memory, in order to serve a new vocation.”[35] The Dada movement bade farewell to its child. “I have closed Dada’s eyes”, wrote Peret in the fifth number of the journal, “and now I am ready to go, I look to see from where the wind is blowing, unconcerned about what will happen next or where it will take me.”[36]

Breton’s lead article in the following number was called “The Outlet of the Medium”. The former Dadaists found their means of tapping the subconscious in the enthusiasm for spiritualism and for everything supernatural that was common in Paris after the war: in spiritualist séances, automatic writing and the narration of dreams. They were drawn to word-play, and preoccupied with the mystery of the telepathic link between Duchamp, who was in America, and his young protégé in Paris, the poet Robert Desnos. Later, Breton recalled his first encounter with the mystery of the dream: “In 1919, my attention focussed on the sentences, more or less fragmentary, which, when one is in complete solitude, just before going to sleep, one’s mind is able to pick up without being able to detect any prior purpose behind them. One evening, in particular, before going to sleep, I apprehended, clearly articulated, …a fairly bizarre sentence, which reached me without carrying any trace of the events in which, according to my consciousness, I found myself involved at that moment, a sentence which struck me as insistent, a phrase, I would venture to say, that felt like it was banging at the window-pane… it was something like: “There is a man cut in half by the window.”“[37] At that moment Breton was passionate about the methods of research into the human psyche which Freud had used, and which he himself tried to use in the course of his professional experience with patients during the war. He came to the conclusion that “the speed of thought is no greater than that of words, and that it does not necessarily challenge the tongue, or even the pen moving across the paper.” Breton shared his revelation with Philippe Soupault, and it was actually then that they got down to work on “Magnetic Fields”, putting into practice the method of automatic writing.

Yves Tanguy, The Hand in the Clouds, 1927.

Oil on canvas, 65 × 54 cm.

Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart.

Oscar Domínguez, The Hunter, 1933.

Oil on canvas, 61 × 50 cm.

Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao.

The young Parisian poet René Crevel turned out to be a medium, and when in a state of hypnotic trance he would utter strange phrases. Crevel had brought out the Dadaist journal Aventure in 1921 along with Francois Baron, Georges Limbourg, Max Moris and Roger Vitraque. He agreed to Breton’s proposal to participate in spiritualist séances. As a result, his gift drew the future Surrealists into the passion for spiritualism. In this way, according to Aragon, by the end of 1922 “an epidemic of sleeping hit the Surrealists… Seven or eight of them came to live only for those instances of forgetfulness when, once the lights were out, they spoke unconsciously, like drowned people in the open air…”[38] After that there arose a fashion for “speaking one’s dreams”, even though for this there was actually no need to sleep. This period in the history of Surrealism was later called “the era of rest”.

Unable to resign himself to the death of Dada, Tristan Tzara tried in July 1923 to organise a performance at the Michel Théâtre in Paris entitled “Evening of the Bearded Heart”. Although the evening did have the expected impact, it ended with a fight on the stage between Éluard and Tzara, and the involvement of the police. The Dada era was already in the past. Dada had performed its destructive role, and on its ruins a new movement was now in the process of being constructed – Surrealism. Dada had assembled so many outstanding people in Paris from many different countries, that a brigade of construction workers was already on stand-by. Dada had developed numerous new concepts and ideas, which Surrealism was later to use. But the main thing was that through Dada, the major artists of Surrealism became Surrealists.

However, it seems that too much was destroyed. Dada strove to deprive literature and art of everything in it that was romantic and lyrical, of everything that stirred and roused the impulses of the soul. When the science of psychoanalysis, the spirituality of Symbolism, and the romanticism of all the centuries of the past were all combined together and then added to the anarchism and absurdism of Dada, the result was Surrealism.

Frida Kahlo, The Love Embrace of the Universe, The Earth (Mexico), I, Diego and Señor Xólotl, 1949.

Oil on canvas, 70 × 60.5 cm.

Private Collection, Mexico.

Charles Rain, The Green Enchanter, 1946.

Oil on masonite, 20.3 × 20.3 cm.

Phillip J. and Suzanne Schiller Collection.

29

Quoted in Michel Sanouillet, op. cit., p. 87

30

“Les Sentiments sont gratuits”, André Breton, Philippe Soupault, Les Champs magnétiques, Paris, 1971

31

“L’Eternité”, André Breton, Philippe Soupault, ibid., p. 110

32

Quoted in Michel Sanouillet, op. cit., p. 141

33

Tristan Tzara, op. cit., p. 188

34

Quoted in Michel Sanouillet, op. cit., p. 228

35

Ibid., p. 325

36

Ibid.

37

Quoted in Maurice Nadeau, Histoire du surréalisme, Paris, 1964, p. 44

38

Aragon, “Une vague de reves”, Nadeau, ibid., p. 47