Читать книгу Deserted - Nathan Roberts - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеI remember being a little kid and lying on the carpet as I stared at the pictures in the illustrated children’s Bible while adults read me the stories about Moses and Pharoah, Noah, and Eve. The characters were all drawn as doe-eyed white people with washed hair and long, clean robes. They didn’t look like the people who lived under a hot sun in the middle of the desert. They looked more like adults from my church playing dress-up. My Sunday School teacher had sang to us, Father Abraham, had many sons. And I am one of them and so are you, so I assumed pale skin was a family trait that went all the way back.

When I was in 3rd grade I was given my own copy of the full Bible, the adult Bible. I eagerly reread all my favorite stories and I found, much to my delight, that there were many salacious details that my picture Bible had conveniently omitted. There was sex and violence on practically every page. I was in possession of a book I would have never been allowed to read if it didn’t have the word “Holy” on the cover. By the time I graduated high school, I had read the full Bible cover to cover four times.

It wasn’t until my mid 20s that I began to read theses stories in the original Hebrew language. The stories felt very different. The verses in English had felt smooth and reliable. The tone and vocabulary was even and polished. But when I read these same verses in Hebrew, they felt stilted. The story of Noah and the ark bore the scars of being edited. The sentences had been broken and mended. The tone and phrasing shifted sometimes in the middle of a story. As I reread Genesis it happened in story after story. The whole book of Genesis felt collaged together from different writers. All this had been polished over by the English translators.

I began to research. That’s when I discovered the Source Theory. I learned that the stories I had grown up reading in the Bible, were actually retellings of stories. Hebrew fathers told their sons about Isaac and the goat as they wandered the hills in search of fresh grazing land. Mothers told their daughters about Eve and a talking snake around the cooking fire. These were family stories told and retold across the desert for hundreds of years. And like so many family stories, they changed and grew with each retelling.

Then around 1000 B.C. Hebrew priests in Jerusalem began collecting these stories, and for 500 years they filled scroll after scroll. Until 587 B.C. when Israel lost a long, brutal war with the Babylonian empire and the capital city of Jerusalem was destroyed. The Hebrew people were enslaved, children were separated from their parents, scrolls were burned, and for the first time Hebrew stories fell under threat of being lost and forgotten.

So the Hebrew priests decided to collect their people’s stories, poems, and songs, and place them alongside laws and rituals. These enslaved priests become the editors of what we now know as the Hebrew Bible.

The original Hebrew text still bears the scars of their editing. Over the centuries different versions had emerged in different villages. And when there were two treasured versions of a story, the editors sometimes chose to catalog them side-by-side in the text. The starkest example of this is the two creation stories—the story of the all-powerful creator of the universe, placed beside the very emotional Yahweh walking next to Adam and Eve in a small garden. Sometimes they wove two versions together, as in the story of Noah and the ark. If you read closely you can see that everything happens twice. The animals are loaded on the ark twice, earth is flooded twice, Noah sends out a raven first, then a dove. And in the Hebrew these couplets make the text feel stilted. Broken and mended.

When I learned this, I felt, well, shocked. I felt lied to by the English translators and tricked by the pastors who told me over and over again that the Bible was a historical account. These stories were what really happened, they’d told me.

But it was around this same time that I met a village elder from the Pokot tribe of northern Kenya. Michael Kimpur grew up in a nomadic community. He herded cows and listened to his village elders retell stories around campfires. When I asked him if there was a written collection of the stories of his people, he told me something that changed my perspective on the Bible. “There are no official versions of our stories,” he said. “It is the responsibility of the elders in each generation to retell these stories in a way that meets the needs of the next generation.”

Shortly after this exchange, I was in the religion section of an old bookstore, my head tilted sideways reading book titles. I stumbled across a collection of Jewish folk retellings of Biblical stories called midrash. The collection contained wild and fantastic retellings that had been told and retold by rabbis over thousands of years. These rabbis played with the details. In one retelling of Adam and the garden, Adam is created as a giant, so big he can barely fit on the earth, his head reaches all the way to the stars. And when this oversized and overconfident Adam begins to question the judgment of the angels, he is shrunk down to normal human size. The story ends with Adam sleeping, dreaming of being a giant and walking among the stars.

In comic books they call these types of stories an Elseworld story. A story set in a world where things are just a little different. A great example of an Elseworld story is Superman Red Son by Mark Millar. In Red Son baby Superman’s alien shuttle flies from the exploding planet of Krypton through space, but it doesn’t land in the Kent family farm in Kansas. Instead, his shuttle lands in the Soviet Union on a collective farm with a Ukrainian family. Changing this one detail about Superman’s story, changes so much.

Superman still has the power of flight and super strength. But he doesn’t fight for “Truth, justice, and the American Way.” Instead Superman is heralded on Soviet radio broadcasts “as the Champion of the common worker who fights a never-ending battle for Stalin, socialism, and the international expansion of the Warsaw Pact.” And readers are suddenly faced with the harsh reality of how terrifying Superman’s power is when he is working for Stalin.

Sometimes all it takes is changing one detail to see a familiar story in a whole new light.

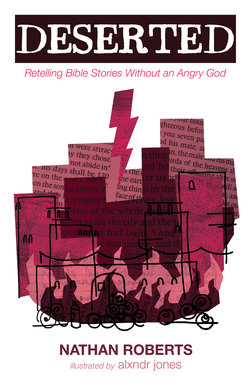

The book you are holding is a collection of reimagined stories from Genesis and Exodus set in a Biblical Elseworld. If you grew up with Bible stories, I suspect the setting and characters will feel familiar, but I did change one little detail–in these stories the Hebrew God, Yahweh, doesn’t exist. Why take Yahweh out of the Bible you ask? Because I wanted to see what would happen next.

I hope my stories inspire you to play with the Biblical details so that we can meet the needs of this and the next generation.

Nathan Roberts