Читать книгу Beyond Evil - Inside the Twisted Mind of Ian Huntley - Nathan Yates - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

THE FIND

It was an everyday scene in the Suffolk countryside. A bright August sun shining on a land of low hillocks and copses, the trees heavy with the green leaves of late summer. At this isolated spot a mile and a half north of the nearest village, Lakenheath, there was little to disturb the silence apart from the occasional deep boom of a jet landing or taking off from the adjacent airbase. In the quiet earth track leading up to the twelve-foot-high wire fence shielding the military property, the only movement to be seen were the walking figures of local gamekeeper Keith Pryer and his friends Adrian Lawrence and Helen Sawyer, who were treading the bank of the roadway a few yards from a pheasant pen.

Keith had parked his four wheel drive Isuzu where the track, called Common Drove, ran between two rows of beech trees and entered a wooded area known as The Carr. At this point, around 12.30pm on Saturday August 17 2002, the trio were wading through the overgrown verge 600 yards from where Common Drove joined the partially tarmacked road to the hamlet of Wangford. The trees, the sunshine, the sound of the 600 fledgling pheasants cheeping softly in the wood – there was nothing to suggest that the scene of pastoral peace was about to be ruptured by the most unimaginable horror. Nothing, that is, except for the strange, terrible smell which seemed to emanate from somewhere in the ditch.

Keith was used to the odours of the countryside, but there was something unusual about the pungent, sickening stench he had noticed in this area over the past few days. It was so distinctively unpleasant that he and his companions had decided to find out what was causing it. They thought perhaps a farmer had dumped manure in the woods, or maybe a dead sheep. In their darkest nightmares they could not have imagined the truth. Suddenly, Adrian, who was leading the party, gave a shout. He turned, his face white with shock, and yelled to his girlfriend: ‘Don’t come any further Helen – get back in the van.’

Keith approached and peered into the ditch. What happened next was to stay fixed in his memory, probably forever. Scanning the damp soil in the bottom of the five-foot-deep cutting, he could see there was a strange object lying there. For a split second, he could not make out what it was – then the shapes leaped into focus. He could make out the outline of what could only be a body. Covered in a shallow coating of grime, it was a body so small and fragile it had to be that of a child. It was badly disfigured, blackened and burnt to the point where the tiny skeleton was showing through the charred remains of the flesh. And lying next to it was another, equally pitiful, equally blackened figure. They were barely recognisable as human. They had been placed carefully side by side. As police officers would later relate with revulsion and astonishment, it appeared as if whoever had put them there had taken meticulous pains to destroy them. Their flesh had been burnt to the point where they had become, in the words of pathologist Dr Nat Cary, ‘partially skeletonised’.

The heartbreaking sight left Keith instantly sick, as if his stomach had turned inside out in a split second. Staggering in a state of confusion, he had no idea what to do or what to think. The 48-year-old gamekeeper is himself the father of two grown-up children, and he had been following the events in Soham, just across the county border in Cambridgeshire, with the fear and foreboding shared by much of the nation during this period of August 2002. This quiet, moustached figure is regarded as a capable character, not easily put off his stride. His work looking after game birds on a 4,000 acre estate made him familiar with the natural cycle of life and death, and he was not at all squeamish when it came to carrying out his job. But nothing in his experience looking after pheasants could have prepared him for this. Somehow he and Adrian managed to get back to the jeep and call the police.

To this day, the gamekeeper finds it disturbing to talk about the horror he witnessed. ‘I wasn’t prepared for what I saw,’ he said. ‘There were what appeared to be two very badly decomposed human bodies lying side by side. I noticed the smell of rotting flesh.’

According to Keith’s friend, farmer Brian Rutterford who works the surrounding land, what Keith saw on that day was truly the stuff of nightmares. ‘It was horrific,’ said Brian, who rents the fields in this area from the well-known East Anglian landlords Elvedon Estates. ‘Keith is a proper family man and this has really shaken him. I think it’s worse if you’ve got kids of your own because you can imagine all too well what the parents are going through. I was one of the few people he managed to talk to just after he had found them and he told me exactly how he had found them, exactly what they looked like. Apparently they were very badly destroyed, so you couldn’t tell straight away what they were. And whoever did it put them side by side in the ditch. It was horrible, not the sort of thing anyone would ever want to see. He was trembling all over, very, very shocked and scared.’

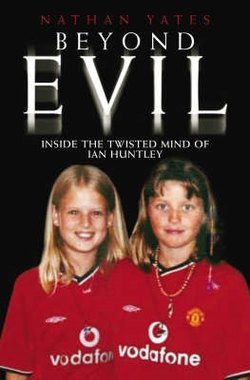

Keith would be reminded of his grisly discovery the next day and every day for months afterwards as he was forced to walk past the spot to continue feeding his birds. The walk would become a matter of endurance for him as he struggled to come to terms with what he had found, and each time he went past that place he would wish that he had not been in the group which made the discovery. But those details of analysis would come later. At that moment he retained just enough composure to realise what the rest of the world realised soon afterwards: that these were the remains of Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman, two healthy, happy young girls just 10 years old, who had vanished without trace 13 days ago from the town of Soham, in neighbouring Cambridgeshire.

Over the past fortnight, hundreds of police officers had been scouring the countryside for signs of the girls, digging up hedges, dredging rivers and carrying out door-to-door enquiries. Their parents, Kevin and Nicola Wells and Leslie and Sharon Chapman, had endured a living hell as everyone – local people, policemen, journalists and the public watching the television news or reading the papers – hoped against hope that the girls would be found alive. Since Holly and Jessica disappeared from the Wellses’ home shortly after 5pm on Sunday, 4 August, the search for them had become a national event. In workplaces, pubs and cafés across the land people were talking about the missing schoolgirls and hoping they would be found safe and well. The two families had suffered a very public ordeal as the search went on; they staged a series of agonising press conferences, facing the cameras to speak of their torment in a desperate attempt to move an abductor to pity. Detectives struggled to piece together the minute detail of the girls’ final movements but, of all the theories voiced by all the witnesses, few suggested the girls had been snatched by a 28-year-old caretaker whom they knew and trusted. Only hardened policemen and reporters thought there was something odd about Ian Huntley’s part in the story.

Privately, there were many, including the parents, who had a gut feeling from the beginning that this was a case of kidnapping. Experienced policemen and journalists at the scene knew it was unlikely the girls would ever be found alive. As the days ticked by, those uncomfortable private views came more and more to the forefront of people’s minds. Yet still, just under a fortnight after Holly and Jessica had vanished, there was the temptation to hope against hope. When Keith Pryer found the bodies in the ditch, the hope shared by millions was finally demolished. All the theories had turned out to be wrong, all the searching had come to nothing. It was a sickening blow, and it is little wonder that the man who suffered it first-hand felt physically ill.

Thousands of people from all over the world had been sending in their messages of support for the families of Holly and Jessica. Soon they would be sending their messages of mourning instead, either by email or by letter or in the form of bunches of flowers. The bouquets would pile high in the grounds of St Andrew’s Church in Soham, in scenes reminiscent of the public mourning for Princess Diana or the Queen Mother.

For Keith and Brian, as for others involved in this extraordinary case, its most puzzling and perhaps most disturbing feature was the senseless savagery of the murders, a savagery cloaked in a sick appearance of care. Someone had committed a double child murder, a crime which could hardly be surpassed in its gruesome and callous nature. Yet this same person had driven these girls to an idyllic spot in the countryside and laid them to rest side by side. It would later emerge that that someone had also posed as the girls’ friend, almost like an older brother, and that his girlfriend, who helped conceal his guilt, was regarded as a kind of sister to them.

Those responsible were not paedophiles who snatched the girls from the street and bundled them into the back of a van, but a young man and woman who knew them and their families, who were well thought of in the local community. These were the disturbing paradoxes of a killer who acted as though he cared, of a caretaker who killed.