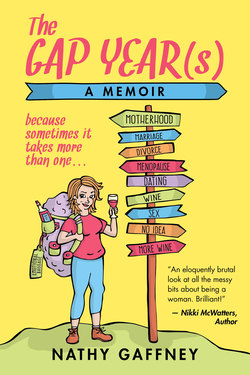

Читать книгу The Gap Year(s) - Nathy Gaffney - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Past Its Use By Date The beginning of the end…

ОглавлениеI have a habit of ignoring warning signs. There have been mornings I’ve gone to the fridge to get milk for my tea, only to find that the milk is out of date. For many people, even the faintest hint of sour means turfing the lot immediately. They’ll bin it without a second thought.

Not me. Maybe it’s my optimistic nature, but I like to give situations the benefit of the doubt, and so I’m conflicted. The dilemma freezes me in mid-air, fridge door open, cold air spilling onto my bare feet.

I need my morning cuppa. My heart doesn’t start beating until I’ve had it. It’s been my daily ritual since I was a little girl, when I would wake pre-dawn and hear my grandma already busy in the kitchen preparing meals for the day. She would offer me hot Milo, but I wanted what she was having, so she would make me strong milky tea with one sugar and we would sit at the yellow laminated Formica table and talk about the ducks.

While many country people keep chickens for eggs and the odd Sunday roast, my Grandma kept ducks. Although Grandma Eileen was quintessential in many ways – blue rinsed hair, and spent most of her time cooking, cleaning, sewing, and tending her garden and her beloved ducks – she also had a fearless side, once beheading a six-foot Mulga snake (also known as the King Brown snake and highly venomous) in the backyard with a shovel, then proudly draping the headless carcass over the hills hoist, so the men could see it when they got home. She also taught me how to pluck feathers from the very ducks she fed and loved, in order to create the ultimate roast duck dinner. These days, my wonderful grandma is long gone (and so are the ducks), but the morning ritual lives on.

A lack of tea can (and has been known to) unhinge the start of a perfectly lovely day. It’s all but unthinkable to go without it.

I check the date again (it hasn’t changed). I rummage through the fridge, peering behind the forgotten jars of anchovies and the massive family-size block of cheddar cheese that now resembles a yellow house brick due to its not being resealed after opening. There is no other milk. This one is two days out of date... should I take the chance? Clearly, it was okay yesterday, because I either didn’t notice or didn’t care, but two days?

I open the bottle and cautiously lower my nose. The smell doesn’t knock me out with that ‘Congratulations! you’ve just made yogurt’ smell. This is a good sign. My tea sits forlornly on the bench, the English Breakfast tea bag slowly releasing the irresistible flavour that will help me face the day.

‘Bugger it!’ I think, and I pour.

It’s risky business, I know, but there is tea at stake here!

What happens next is one of two things. The milk will either curdle immediately, like someone has dropped a tablespoon of cottage cheese into my tea, the result of which is a quick realisation that my olfactory radar is way off, and I’ll tip the whole of it down the sink.

Or, I’ll sip my morning cuppa with a tentative internal holding of the nose: my attempt to shut my taste buds off to the undeniable fact that I’m willingly imbibing something that would not pass a food safety audit.

Either way, not an ideal outcome.

I’d like to say I’ve done this only once, that I learned my lesson and now ditch anything past its use-by date. But I’d be lying. I’ve done it countless times over the years.

My marriage was like that milk. Past its use-by date. Yet, with it, too, I had stubbornly and dutifully persisted, attached to the hope that it would somehow get better and become the marriage, the union, the partnership I willed it to be. Attached to the ritual of it maybe… the morning kiss, living together, the dream. The fairy tale. My ex-husband – if you asked him would be highly likely to give you a different version of events. I am neither blameless nor unsullied in the demise of my marriage. Things just went wrong, or were wrong. Hell, maybe we were mismatched from the start. We tried to fix ‘us’, and we tried to grow together, but it just didn’t seem to work. Little things that got swept under the carpet in order for us to not deal with them gathered more and more dust, but didn’t disappear. It was a bit like telling yourself you’re spring cleaning, but really you’re just shoving shit in cupboards and hoping the doors will hold.

Differences in our personal styles were part of it. I’m a morning person, love the sunrise, and am brightest in the a.m. Andy, on the other hand, is a night owl. 11 p.m. ticks around and he would be just waking up. He’s a photographer, and many latenight hours were spent in his dark room. Whilst I loved the fact that I was married to this creative soul, in my early 30s I was living in the bubble of how perfect relationships are supposed to operate and I hated going to bed on my own.

We had disagreements, sure. No surprises there, as most couples do, but it was the handling of our differences that didn’t fit. When I wanted to talk things through, he withdrew. I wanted to save money for our future; he didn’t see the point. I wanted to fill our weekends with friends and socializing, but he preferred having me to himself. We connected in many areas, for sure (that’s why we were together in the first place, and there were good times – great times!). There are good times in all relationships before they go wrong, but that’s not what this book is about. The fact is that, as many factors as there were that drew us together, there were more that flagged warning signs to tell us this was NOT a match made in heaven.

Should we have married at all? If it hadn’t been for visa reasons, we possibly wouldn’t have. When we met, I’d been back in Australia (after four years overseas) for less than twelve months and Andy was on a tourist visa, which was going to expire. We were in the heady throws of a fledgling love affair that we didn’t want to end, and we took the advice of a friendly immigration lawyer who, after meeting with us, said: “Honestly, guys, if neither of you are opposed to the idea, the cheapest, fastest, and most guaranteed way of being able to stay together in Australia is to just get married.”

(Note to reader: Kids – don’t try this at home. It was the early 90s then, and Australia’s immigration laws have since tightened up… a lot!)

So, we walked out of his office in Bondi Junction, and it pretty much went like this.

Me: “What do you reckon?”

Him: “Oh yeah, I’m okay with it. You?” Me: “Yeah, why not?”

And that was that. No bended knee, no engagement ring, no fanfare. Andy returned to the UK for 3 months when his visa expired, and then re-entered Australia with a fiancé visa on the proviso that we would tie the knot within six months. Eighteen people attended our small, intimate wedding about five and a half months later, and that was it; in the eyes of state and church, we were hitched.

Not quite the romantic ‘I can’t imagine my life without you’ declaration, but once you’ve committed, once you’ve married – ‘til death do we part and all that – it’s not comfortable to admit that you think you might have been too hasty. I wanted to believe that this was my forever. I really, truly, Catholically did. (Amazing what that conditioning does to/for you, eh?)

I loved being married, and for the first few years we did all the ubiquitous newlywed things. We set up house, bought furniture, decorated, nested, entertained friends, partied, and travelled, but when the distractions of all the ‘stuff we did’ were laid to one side, I’m not sure our marriage ever had the solid foundations marriages need in order to endure over a lifetime. It was in the still moments when I noticed the little cracks that were starting to emerge. We busied ourselves papering them over, but there was no doubting they were there.

Our marriage was like an old house on a great block of land with fantastic views. Overall, the project had potential, but we could never decide whether to renovate or detonate.

Five years prior to the ultimate death knell and our final parting, we trial separated for six months, but reconciled, hopeful (if not determined) that, with effort and the best of intentions, we could make our marriage work.

We couldn’t.

When we separated the second (and final) time, we both agreed on one thing: we should have stayed apart the first time. But the combination of a young child, a persistent and opinionated therapist, genuine love for each other, and a desire for things to get better saw us working at our marriage for another five years, until we could no longer pretend anything but the truth. The milk was sour. In fact, more than just sour, it had well and truly curdled. We were no longer fighting the good fight; we were just fighting. It was time to concede.

And just like off-milk, it left a bad aftertaste. Sad bitter discontent mixed with regret and resentment: both for each other and for our marriage. It was like watching an investment portfolio freefall from glory, knowing deep down that you didn’t get out in time and that the market is never going to bounce back.

Nothing we could do for each other was good enough. When we were together, I felt so constricted that I couldn’t breathe properly. The only thing I could do to catch oxygen was to lift my shoulders and gasp. It was like my nose was pressed against the roof of a car that had free-fallen off a bridge and was sinking. Shallow, heaving gasps, and I still couldn’t get enough air. I was trapped inside my body, suffocating in a vacuum of grief, which in turn radiated outwards. My friends could see it, my family could see it, and worst of all, our son could see it.