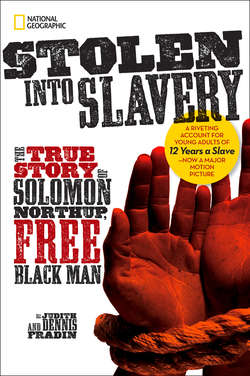

Читать книгу Stolen into Slavery: The True Story of Solomon Northup, Free Black Man - National Kids Geographic - Страница 8

(Illustration Credits 1.5)

ОглавлениеALL 13 AMERICAN COLONIES ALLOWED SLAVERY DURING the 1600s and 1700s. Not until 1780—four years after the colonies declared themselves to be the United States of America—did Pennsylvania become the first state to outlaw slavery. Other northern states also made slavery illegal, but some took their time doing so. Solomon Northup’s home state, New York, didn’t outlaw slavery until 1827.

The black mother’s status determined that of her children in the slave states. If the mother was a slave, her children were, too. If the mother was a free black, so were her children.

Solomon Northup was born in Minerva, New York, 100 miles south of the Canadian border and 200 miles north of New York City. Solomon claimed that he had entered the world “in the month of July, 1808.” Since Solomon’s mother was a free black woman, he was born free.

On his father’s side, Solomon’s ancestors had been slaves belonging to a white family named Northup. Around the year 1800 Solomon’s father, Mintus, had been freed by the terms of his owner’s will. Mintus had adopted the last name Northup to honor the family that had liberated him.

Solomon was a serious, hardworking child. When he wasn’t helping around the family farm, he loved to read. His favorite pastime, however, was playing the violin. By his teens Solomon was so skillful a fiddler that friends and neighbors hired him to perform at dances and parties.

On Christmas Day of 1829, 21-year-old Solomon Northup married Anne Hampton. Solomon liked to say that the blood of three races flowed through Anne’s veins: Native American, white, and black. The couple had three children—daughters Elizabeth and Margaret and a son, Alonzo.

In the spring of 1834 Solomon and his family settled in Saratoga Springs, a vacation resort 30 miles from Albany, the capital of New York. During the warm months when tourists flocked to Saratoga Springs to bathe in its mineral spring waters, Solomon drove a carriage for the hotels. At other times he worked as a carpenter, helping to build area railroads. In addition, Solomon earned an income from playing his violin. Meanwhile, Anne found employment as a cook in hotels and inns. By pinching pennies, Solomon and Anne managed to squeak by financially. Around Saratoga Springs, the Northups had a reputation for being a close and loving family.

One morning in late March of 1841 Solomon went for a walk in hope of finding an odd job. At the time, Anne was 20 miles away working as a cook at Sherrill’s Coffee House in Sandy Hill, now known as Hudson Falls, for a few weeks. Anne had taken nine-year-old Elizabeth with her. Seven-year-old Margaret and five-year-old Alonzo were being cared for by an aunt in or near Saratoga Springs.

At the corner of Congress and Broadway, Solomon spied an acquaintance of his talking to two white strangers. “Solomon is an expert player on the violin,” his acquaintance explained, while introducing him to the two men. The strangers, who said their names were Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton, claimed to be in need of a violinist. They were headed to Washington, D.C., to meet the circus they worked for—or so they said—and a violinist would attract customers to the small shows they would present along the way. Brown and Hamilton offered to pay Solomon a dollar a day for driving them in their carriage as far as New York City, plus three dollars for each performance and enough money for his return to Saratoga Springs.

Before he was kidnapped into slavery, Solomon drove a carriage like those waiting in front of the United States Hotel in Saratoga Springs, New York, in this early 20th-century photo. (Illustration Credits 1.6)

Excited by the prospect of a windfall, Solomon hurried home and grabbed a suitcase, a few clothes, and his violin. Since he expected to be back home before Anne’s return, he didn’t even stop to leave his wife a note about where he was going. Solomon climbed into the driver’s seat of Brown and Hamilton’s carriage and drove away from Saratoga Springs as happy as he had ever been in his life.

Thirty miles into their journey, they stopped to present a show in Albany. Hamilton sold the tickets, Solomon provided violin music, and Brown amused the audience by juggling balls, walking on a tightrope, and making invisible pigs squeal. This proved to be their only performance en route to New York City, for Brown and Hamilton said they were worried that they wouldn’t reach Washington in time to join up with the main body of the circus.

Once in New York City Solomon expected to be paid and then return home to Saratoga Springs. However, Brown and Hamilton had another exciting proposal. They promised that if Solomon continued with them to Washington, D.C., the circus would hire him for a more permanent job. Touring with the big show for a few weeks, he would earn more money than he made in an entire year in Saratoga Springs.

Solomon accepted the offer. His family could use the money. Besides, he trusted Brown and Hamilton, who seemed to be concerned for his welfare. For example, before leaving New York City they took Solomon to a government office to obtain free papers for him. That way if someone in Washington claimed he was a slave, Solomon could present written proof that he was free. This was important because slavery was legal in Washington, D.C. Any black person in our nation’s capital risked being mistaken for a slave.

When they reached Baltimore, Maryland, Solomon parked the carriage. He and his two new friends boarded a train. With his free papers securely in his pocket, Solomon arrived in the U.S. capital with Brown and Hamilton on April 6, 1841. They checked in at Gadsby’s, the city’s top hotel, on Pennsylvania Avenue down the street from the White House.

Solomon Northup spent the first 32 years of his life a free man in upstate New York. He was then lured to Washington, D.C., where he was sold into slavery. (Illustration Credits 1.7)

Solomon and his companions arrived in the national capital at a time of mourning. Two days earlier President William Henry Harrison had died in the White House after being in office for only 30 days, making Vice President John Tyler the new President. After supper Brown and Hamilton invited Solomon to their room, where they counted out $43 and handed it to him. That was more than he was due, but the two circus men insisted that he take a few extra dollars because it wasn’t his fault that they had presented fewer performances than expected on the way to Washington. They invited Solomon to attend President Harrison’s funeral procession with them the next day. Afterward, they promised, they would introduce Solomon to the circus company owners.

The next day, April 7, a giant funeral honoring the late President was held in Washington. Bells were tolled, cannons were fired, and thousands of people joined the procession on foot and in carriages. Several times during the ceremony Brown and Hamilton invited Solomon to join them for drinks in a nearby saloon. Unaccustomed to liquor, Solomon was soon drunk. While he wasn’t looking, either Brown or Hamilton placed a drug in his drink to make him even drowsier. More than a century later doctors at Tulane University Medical School in New Orleans concluded that Solomon was drugged with belladonna or laudanum, or with a mixture of both potent drugs.

When Solomon returned to Gadsby’s Hotel, his head began to hurt, and he felt sick to his stomach. He lay down, but his head ached too much for him to sleep. Solomon slipped into a delirium. In the dead of night several people entered his room—he thought Hamilton and Brown were among them—who said they were taking him to a doctor. Staggering through the streets, Solomon was led into a building, where he lost consciousness. Instead of coming to in a doctor’s office, however, he awoke in the slave trader James Birch’s slave pen.

Locked in his cell most of each day, Solomon had plenty of time to think. Looking back, he realized that from the morning he had met Brown and Hamilton in Saratoga Springs, the men had tried to win his confidence. They had lured him farther and farther south by convincing him that the circus offered plenty of easy money. By insisting that he obtain his free papers, they had created the illusion that they cared about his welfare. The truth was, there was no fortune to be made working for the circus. In fact, there was no circus. The whole thing had been a scheme to sell him as a slave to Birch.

What about Birch? Had he known he was buying a free man? Solomon was certain of it. But buying a free man was illegal. If it became known that Solomon was no slave, Birch would have to let him go, losing his entire investment. Birch might even be sent to prison for enslaving a black man he knew to be free. Birch had beaten Solomon savagely for claiming to be free so that he would keep quiet about it in the future.

Solomon had learned something from that beating: If he wanted to survive, he couldn’t talk about being free anymore. His wisest course was to keep his eyes open for a chance to escape and to try to send word home that he had been kidnapped.

Two weeks after Solomon arrived in the slave pen, Birch and his assistant entered his cell late one night, carrying lanterns. They woke him up and ordered him to prepare to depart. Before being led outside, Solomon and four of Birch’s other slaves—Clemens Ray, a young woman named Eliza, and Eliza’s young daughter Emily and son Randall—were handcuffed together. As they were marched through Washington, Solomon thought about calling out for help. But the streets were practically deserted, and in a city where buying and selling slaves was legal, who would pay attention to a black man’s claim that he had been kidnapped? He thought of trying to run away, but how far could he get with his left hand cuffed to Clem Ray’s right hand?

Birch led the five slaves to the Potomac River, where he ordered them into the hold of a steamboat, among boxes and barrels of freight. The vessel was soon steaming down the Potomac. When it passed George Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon, the steamer tolled its bell in honor of the Father of His Country. Now that he was a slave Solomon saw things differently. It seemed odd to him that the same people who practically worshiped George Washington for winning his country’s freedom thought nothing of denying slaves theirs.

In the morning Birch allowed his slaves onto the steamer’s deck to eat breakfast. Some birds flying along the shore caught Solomon’s eye. “I envied them,” he later recalled. “I wished for wings like them.”

After a two-day journey via steamboat, stagecoach, and train, Birch and his slaves arrived in Richmond, the capital of Virginia. There Birch brought Solomon, Clem, Eliza, and her two children to a slave pen operated by a Mr. Goodin.

Goodin examined the five captives. When it was Solomon’s turn, Goodin felt his muscles. He also inspected his teeth and skin, as if considering the purchase of a racehorse. “Well, boy, where did you come from?” Goodin asked, after finishing his examination of Solomon.

Without stopping to recall Birch’s insistence that he was a runaway slave from Georgia, Solomon answered, “From New York.”

“New York!” said Goodin, aware that it was a state where many free blacks lived. “Hell, what have you been doing up there?”

When up for sale, slaves had to act agreeable while having their muscles and teeth inspected. Failure to do so could result in a whipping. (Illustration Credits 1.8)

Birch looked like he was about to kill him, so Solomon quickly explained that he had just been visiting New York. This seemed to satisfy Birch. For some unknown reason, Birch decided to keep Clemens Ray, whom he later took back to Washington with him.

Solomon spent only one day in Goodin’s slave pen. Just as Brown and Hamilton had sold Solomon to Birch in Washington, Goodin planned to send him farther south for sale at an even higher price. The next afternoon Solomon and 40 other slaves, including Eliza and her two children, were marched onto the Orleans, a sailing vessel bound for New Orleans, Louisiana.

The Orleans floated down the James River, entered the Chesapeake Bay, then worked its way into the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Having studied geography, Solomon had a much better idea of their course than the other slaves did. They were heading down the East Coast, intending to reach New Orleans by sailing west around Florida.

The Orleans was manned only by its captain and a crew of six. They needed help with the shipboard tasks, so the slaves’ handcuffs were removed and each of them was assigned a job, such as cleaning the vessel or waiting on the crew. Solomon headed the cooking unit and organized the distribution of food and water.

Off the coast of Florida the Orleans was battered by a violent storm that placed the ship in danger of sinking. Hoping to keep the vessel afloat, the captain sought shelter in the islands of the Bahamas. There, while they awaited a favorable wind to continue their journey, Solomon decided that the time had come to make a bold strike for freedom. He was by nature a gentle man, and the prospect of killing members of the ship’s crew repulsed him, but he knew that he might have to do so if he ever expected to be free.

From Washington, D.C., Solomon was shipped to New Orleans, where he was purchased by William Ford. (Illustration Credits 1.9)

Solomon had befriended two fellow slaves on the Orleans with whom he had a lot in common. One of them was another free black man named Robert who had a wife and two children in Cincinnati, Ohio. Robert had been promised a job in Virginia, but upon arriving there he was kidnapped and sold to Goodin’s slave pen in Richmond.

Arthur, his other shipboard friend, was also a free black man with a family. Arthur had been a bricklayer in Norfolk, Virginia. Late one night while returning home from work through an unfamiliar neighborhood, he was attacked by a gang of white thugs who had sold him into slavery.

Solomon discussed his plan to take over the Orleans with Robert and Arthur. He pointed out that when the sailors locked the slaves in the cargo hold at night, they never did a head count to make sure everyone was present. There was a small boat on the deck of the Orleans. By hiding beneath it, Solomon could avoid being locked in the hold at night. Then, while the others slept, he would climb out from under the little boat and release Robert and Arthur from the hold.

Next, the three of them would grab the pistols and cutlass in the captain’s cabin and take the captain and crew prisoner, shooting anyone who resisted. They would then sail the ship up to New York City, where authorities were likely to sympathize with them. Solomon and his two accomplices kept their plan secret because slaves caught plotting a revolt could be put to death.

Soon after Robert and Arthur agreed to his plan, Solomon tested whether the little boat was a good hiding place. When the slaves were ordered into the hold for the night, he slipped away and hid beneath the boat. At dawn he sneaked out without anyone noticing and joined the other slaves emerging from the hold.

The three men decided to strike as soon as the Orleans departed the Bahamas. Finally, a favorable wind stirred, and the Orleans pulled up anchor and set sail. But before they could seize the vessel, Robert became ill with smallpox and died. He was buried at sea, a thousand miles from his home and family in Cincinnati. The plan for seizing control of the ship died with Robert because Solomon and Arthur could not do it by themselves.

An evening or two after Robert’s death, Solomon was resting on the deck when a sailor asked why he was so downhearted. The sailor, Englishman John Manning, seemed sympathetic, so Solomon decided to take a chance. He explained that he was a free man from New York with a wife and three children and that he had been kidnapped. Manning listened closely and then offered his help.

Before they parted, Solomon asked Manning to meet him in a front section of the ship called the forecastle at a certain time the following night, and to bring pen, ink, and paper with him. The next night Solomon once again avoided being locked in the hold by hiding under the little boat. In the middle of the night he crawled out and went to meet Manning.

When Solomon reached the forecastle, Manning motioned him to sit at a table where he had placed pen, ink, and paper. Solomon then began to do what very few slaves could do: write a letter. White Southerners feared that educated slaves might pass notes to each other and plan a big rebellion. That was why southern states had numerous laws forbidding slaves, and sometimes even free blacks, from learning how to read and write. White people who dared teach African Americans in defiance of the laws faced punishment themselves.

For example, in 1829 Georgia passed a law providing a fine of $500—about $12,000 in 2011 dollars—and possible imprisonment for any white man or woman who taught a black person—slave or free—to write. In 1830 Louisiana and North Carolina passed laws forbidding the teaching of reading and writing to slaves. The penalty for educating a slave in Louisiana was a year in prison. Two years later Alabama and Virginia enacted laws subjecting white people to a fine and a whipping if they were caught teaching blacks to read and write.

As a free black person growing up in New York, Solomon had obtained a fine education, so he could read and write very well. Sitting at the table with John Manning, he wrote a long letter to Henry B. Northup, a lawyer from Sandy Hill, New York, who was a member of the family that had owned Solomon’s forebears. In his letter Solomon said that he had been kidnapped and was headed for New Orleans aboard the Orleans. Unfortunately, he didn’t know who would buy him and where he would live, but he hoped Mr. Northup would inform his family that he was still alive and in the New Orleans area so they could track him down and rescue him.

John Manning promised to mail Solomon’s letter from the New Orleans post office. A day or two later the ship arrived at the Crescent City with its cargo of slaves. Shortly after the Orleans docked, Solomon witnessed a remarkable scene. Two men boarded the vessel and informed Arthur that he was a free man and that his kidnappers had been arrested and jailed. As he left the ship, Arthur danced about with happiness. But when Solomon looked at the crowd on the wharf, he saw no familiar faces come to liberate him.

Yet he knew he had one friend among the crew. As he left the Orleans, John Manning looked at Solomon over his shoulder. Solomon thought Manning’s glance was to let him know that he hadn’t forgotten about mailing his letter.