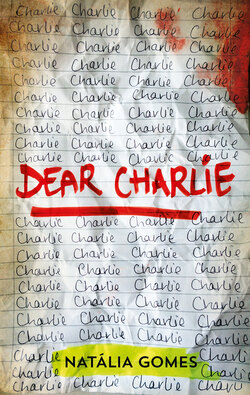

Читать книгу Dear Charlie - Natália Gomes - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter 2

‘Everything Must Go’ (Manic Street Preachers, Summer 1996)

‘So, how do you feel?’

Although this was only my third session, Dr Albreck had already fed into every stereotype one could have about a therapist – leather sofa, plant in the corner of the room, box of tissues within reach, and the occasional smile and nod to remind me that she was still listening. And, of course, she always asked me, ‘How do you feel?’

Honestly, I didn’t know how I felt. I never did. Even if I could identify just one of the emotions that stirred within me, I wouldn’t want to give it to her. All she would do with those words is write them down in her black leather notepad. She wouldn’t absorb them. She wouldn’t understand them. And she certainly wouldn’t help me feel any differently.

‘Fine,’ I finally answered.

‘What does “fine” mean, Sam?’

‘I’m not sure how to exactly describe it. I don’t have a dictionary with me.’

She smiled, although I could tell it wasn’t genuine. ‘What I mean is, “fine” isn’t a feeling.’

I stared at her, biting my lip while waiting for a chance to unload all of my thoughts like a heavy suitcase being unpacked after a long journey. There had been so many words written in the newspapers about how my family should feel – ashamed, guilty, ignorant. It didn’t matter how I felt, or what words I used to describe it because there would always be someone ready to tell me what to feel. I just wished someone would tell me what to say.

‘I can see this is a difficult question for you, as usual. So, let’s start with something easier. When is your first day of school?’

‘Two weeks on Monday.’

‘And how do you feel about that?’

There it is again – the need to talk about feelings. ‘Well, I’ll be starting a new school where everyone will know my name before I even step into the building, so I guess I don’t feel fine.’

‘Good.’ She leaned forward in her chair, apparently pleased with my response. ‘Sam, everyone who has faced – and survived – a traumatic event like you have finds themselves at what I like to call a “Turning Point”. It’s at this point where you decide whether you want to let go of everything and move forward, or stay stuck in the past. This new school could be your turning point. You should consider giving it your all. Keeping that in mind, are you planning on joining any clubs or afterschool programmes? They provide wonderful opportunities to make friends. How about the music club?’

‘I was thinking of joining Teens Against Violence. What are your thoughts?’ I said, crossing my arms and leaning back in the chair.

For a moment I thought she was going to smile but she didn’t. ‘I think that’s a very good idea, Sam. Getting involved in your new school will be the fastest route to immersing yourself into that community. Immersing means – ’

‘ – I know what immersion means.’

‘Of course. You’re a bright young man Sam. Are you still playing the cello?’

‘Piano. Not so much, any more.’ I intertwined my fingers, pressing deep into my knuckles. Resting my hands on my lap, my eyes skimmed over the walls thick with framed certificates and awards. I wondered how much each session with the great Dr Elizabeth Albreck cost. Fifty pounds an hour? Less? More? I considered asking her directly, but I had a more important question on my mind. ‘How long do I have left?’

‘Why do you ask?’

‘Because you don’t have a clock in here.’ I thought that was obvious. Maybe she didn’t know.

‘I prefer not to remind my clients of the passing of time. I want them to feel safe and heard, without the pressure of a clock hurrying them along.’

‘How do you know when the session is over?’

‘It’s over when it’s over.’

‘So, what if I was to sit here all morning?’

‘Why would you do that, Sam?’

‘It’s just a hypothesis, Dr Albreck,’ I smiled. Getting dismissed from therapy might be easier than I had thought.

‘I guess I would ask you to bring whatever thoughts were going through your mind to our next session?’

‘You mean, hurry me along?’

‘No, not hurry you along. But gently inform you that I have other clients to see other than you.’

‘So, you do keep track of time?’

‘Not exactly. Again I don’t like to remind my clients – ’

‘ – But by “gently informing” me, you’d be reminding me of the passing of time, thus adding pressure.’

‘Sam, we’re getting way off topic. Let’s go back to talking about your new school,’ she sighed, uncrossing her legs and then re-crossing them.

‘But we can’t,’ I shrugged, getting up off the sofa and grabbing my hoodie off the edge.

‘And why is that?’ she asked, sliding her glasses off her thin face that wore a tired expression.

‘Because according to the large watch on your wrist that you kept glancing down at, we’re all out of time.’ I leaned over and popped a green mint into my mouth from the glass bowl that sat on the table by her black-skinned planner. And as I pushed open the door to the waiting room, I heard her notebook slam shut.

Unlocking my bike from the metal grid in the car park, I swung a leg over and pushed my foot down hard on the pedal. Dr Albreck’s office shrank behind me until it became no more than a dot in the distance. Only seven more sessions to go. Four hundred and twenty more minutes that I would have to sit on that leather sofa and face questions that I didn’t have the answers to.

The late summer wind whipped at my face, a non-existent chill stinging my skin. I pedalled harder and harder, faster and faster. The wheels spun wildly like a washing machine, going around and around. I lifted off the seat and leaned to the left, the bike curving around Knockturn Lane onto Knockothie Brae. Small square semi-detached houses lined the streets, their brick roofs blending into one thick blurry stream of red as I sped past. Around the corner into Findhorn Drive, past Market Brae, down onto Pembrook Road – I slammed the brakes on.

There it was. Pembrook Academy. How could I have gone down this way? I should’ve taken the right onto Golfview Road and gone past the golf course. But I didn’t think. Or perhaps I did, and this was where I really wanted to be. My body was ready to confront my ghosts before I was.

My chest heaved in and out, as my lungs struggled to gasp air. Lips parted, eyes open wide, I just stared at the pale-yellow building. It was bigger than I remembered. Or maybe smaller. The rectangular windows, methodically spaced out only inches from each other, were in darkness. Wooden boards covered up the broken windows on the first floor, where students and teachers had tried to escape. A chair lay on its side, having been thrown through the window to break it. Shards of glass still lay on the tarmac beneath the frames. Yellow strips of ‘Do Not Enter’ tape crossed the exit doors and the main entrance. On the front steps lay a black shoe, as if someone had left it behind as they ran from the building.

Several contractors had publicly turned down the opportunity of ‘refurbishing’ Pembrook Academy. I guess no price was high enough to clean blood off the walls. As far as I knew, the school council was trying to hire a company from the city, where the echo of screams was slightly quieter.

I squeezed my eyes shut, biting down on my lip until I tasted warm blood. I could hear them even though I hadn’t been there – the desperate screams, the frantic 999 calls, the smashing of the windows. It was so loud in my ears. I pressed my hands into my ears. ‘Stop,’ I whispered, ‘please stop.’ But it didn’t stop. The screams got louder, more high-pitched, and the sound of glass shattering became deafening.

‘Sam?’

I blinked my eyes open and saw the outline of someone that I used to know, someone that used to be my friend. I opened my mouth to say hello but suddenly that felt stupid. A simple hello wouldn’t be enough. It wouldn’t even come close.

Geoff stood in front of me, his hands trembling as they held a small bouquet of carnations wrapped in thin plastic and tied with yellow ribbon at the bottom. As my eyes skimmed the ground by his feet, I noticed more bouquets and ribbons like his. Flowers, small teddy bears and cards littered the pavement all around the perimeter of the school. Most lay on the ground, resting against the knee wall while others were tied to the metal bars of the gate. There were so many flowers, gifts, messages to loved ones and missed ones. I shouldn’t have been there. I mounted my bike and turned around, slamming down on the pedals as they propelled me away from the school and the people I used to know. And from the friends I used to have.

I could hear Geoff calling to me as I pedalled faster and harder, until I reached my street. A couple of children playing skip rope in a front garden stopped when I cycled past, letting the rope drop to the ground. As I pulled into my driveway, a neighbour across the street stood frozen outside his door, groceries still in hand. I could feel his eyes burning into my back as I pushed open the front door.

‘Sam, is that you?’ my mum called out.

‘Who else would it be,’ I muttered, walking past my dad sitting in his chair with the television remote in one hand and a beer in the other. I shuffled into the kitchen and saddled into one of the bar stools.

‘I had to go all the way to Watford,’ she quietly said, unpacking groceries from a beige straw recycled bag, the edges frayed with use. Having been told by six retailers that she was unwelcome, Mum now needed to shop at a grocer’s fifteen miles away.

I watched as she unloaded the heavy bag – milk, apples, bananas, brown sugar and cinnamon Pop Tarts. I stared at them, the box achingly familiar. ‘Mum – ’

‘ – What is that, Linda?’

My dad carefully edged towards the kitchen counter, setting his beer can down on the granite. He lifted up the box of Pop Tarts, his hand slightly trembling. ‘What is this?’ he asked again, hanging on longer to each word spoken.

‘Charlie will only eat the brown sugar and cinnamon kind. He won’t try any other flavour,’ she stammered, trying to grasp the box back from Dad’s hand. But he shook her off, pulling the box in closer to his chest.

‘Enough,’ he whispered, squeezing his eyes shut.

‘Do you remember when we tried to make him eat the strawberry kind?’ she continued, a nervous smile stretching across her face.

‘I said, enough!’ He slammed the box against the kitchen wall. It caved in upon impact, sending small pieces of the buttery crust flying out in a dust of sugar. It hit the floor, more large crumbs spilling out from the broken open edges.

My mum dropped to the ground, tears spilling from her eyes as she picked up the box and cradled it, as if it was alive. Her back broke into tiny spasms as her tears became louder and deeper, until they violently shook her whole body. I waited for Dad to walk over and comfort her, already knowing that it wouldn’t happen. He turned around and walked back to the living room, sliding into his chair and taking a long swig of beer.

I inched down from the stool and walked over to the linen cabinet. I eased out the broom and dustpan, and gingerly approached Mum on the floor. She huddled protectively over the mess. So I placed the dustpan on the floor and leaned the broom against the wall, and slumped up the stairs.

When I reached the top of the stairs, I noticed Charlie’s door was slightly ajar. Not looking in, I leaned forward and closed it tight. Walking past the framed photos of him as a smiling toddler on a swing and a laughing child at Disney World, I shuffled into my bedroom and leaned on the door. I stumbled back as the door pitched and shut behind me then I slid down until my legs hit the floor and splayed out in front of me.

I tilted my head back, staring at the glow-in-the-dark stickers that had been on my ceiling for almost six years. I remembered the day Charlie and I put them up there. Dad had just taken us to the newsagent’s around the corner. He did that every Wednesday after school. He said it was to help us get through the rest of the school week, although I think he also did it for himself. While he slid a six-pack of lager out from the fridge in the back of the shop, Charlie and I counted out our weekly allowance. We didn’t get much, but it was always enough to pick out a comic or magazine, and a sweet.

On this particular afternoon, I had really wanted a special-edition comic about aliens and distant planets. But I didn’t have enough money, even if I skipped the sweet. Charlie gave me his share. He always did stuff like that for me.

Together with our coins combined, we bought the comic and eagerly ran home with it, Dad trying to keep up behind us. While Mum cooked dinner and Dad sipped beer and watched the football highlights, Charlie and I lay on my bedroom floor and read the comic from front to back. And on the back page were free stickers that promised to glow in the dark. Charlie ripped them out, and balanced on my nightstand as I pointed out the spots in my ceiling I wanted to fill with planetary shapes and intergalactic stars.

At bedtime, when Mum thought we were brushing our teeth, we turned off the lights in the room and stared up at the ceiling in awe. They weren’t bright and didn’t really resemble any planets I had seen in picture books, but they were amazing. They were ours, and no matter how much we drifted apart in our later childhood years, they remained on my ceiling as a reminder of the memories we built together. Now, they reminded me of the lives that were lost that June day and of the earsplitting gunshots I heard in my head at night.