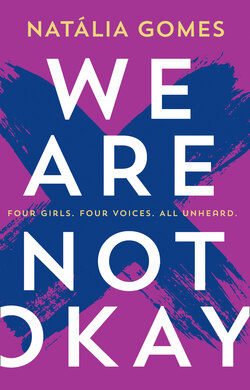

Читать книгу We Are Not Okay - Natália Gomes - Страница 10

ОглавлениеULANA

Those girls.

With their short skirts and heels. Crisp white shirts with the first two buttons undone. Flickers of lace bras during Gym. Edges of pink thongs peeking out from freshly ironed black school trousers.

Those girls.

I feel bad for those girls. They don’t know any different. They see images on TV and in magazines and aspire to be just that, not casting any doubt on the images they’re being sold. They want their hair longer – not creepy long though – shinier, straighter, curlier, blonder but not too blonde. They want to be taller but, of course, not taller than any boy, thinner but…actually, there’s never too thin. They open a magazine and all they see are skinny girls becoming skinnier, and getting praise for it. I see those girls at lunch, conflicted with the daunting choices of calories. Some don’t even eat. Some have just a piece of fruit then say they had a big breakfast. They sip on water. Too much sugar in juice. Too many calories in a smoothie. Too much fat in a hot chocolate. Black coffee works too.

Then they go to the girls’ toilets straight after. Some throw up, others readjust their short skirts and unbuttoned shirts. Most reapply their make-up for the afternoon. Glossy pink pouts. Thick dark eyebrows. Rosy cheeks. Matte noses. Black spider leg eyelashes. Contoured facial bones shimmering in highlighter. They dot concealer under their eyes, hiding the wrinkles they don’t have but always see when they look in the mirror.

I hope they do it for themselves, and not for others. That they’re not just parts of a game, being played, manipulated, moved onto tiny coloured squares for the next position. If not, I feel sorry for those girls. But they probably feel sorry for me. They think that I don’t belong here. That I’m different. That I’m not free, like them. They’re not free, not if they dress and look that way for others, for boys.

I feel a small tug on my hijab and it yanks a kirby grip from my hair. It slides down a little. When I turn I see those girls walking away. They look back at me and laugh. It’s not like this all the time. But when it happens, it’s always the same.

‘Terrorist.’

Some whisper it, while others say it loud enough so I can hear and so can all those around me. I’d be lying if I said it didn’t bother me, of course it does. But that’s what they want. They want to see me angry, see me cry. But I won’t because I’m not ashamed or embarrassed. I know I won’t be any less Muslim if I take off the hijab, I’ll still be me. But I want to wear it because it’s a part of who I am, where I’m from, and what I believe in. So they should be the ones who are ashamed and embarrassed. My parents gave me a choice when we first moved here, and although I don’t wear a face veil like some girls and women back home, I’ve kept the hijab. I remain devoted to my faith, to my family, and to myself.

In all but one way.

Some might say, the worst way.

Sometimes I wish I wasn’t the only Muslim here at this school, that I had someone else my age to talk to. I have Sophia, I know. She’s a good friend to me. But sometimes I wish I had someone who understood more about my background. Someone who, maybe, was also going through what I’m going through – so I could speak to them about it. But I don’t have anyone like that. Surely my parents considered that I’d be the only Muslim high-school student in this small village. The nearest mosque is almost a forty-five minute bus ride away.

‘Hey!’ Aiden from my chemistry class starts to chase them down the hallway but I hold my arm out to block him, being careful not to touch him or for him to touch me.

‘Don’t bother,’ I say, bending down to pick up my folder.

‘I’ll get it.’ He gets down there first and scoops it up. ‘Here.’

‘Thanks.’ But when my fingers latch on, he doesn’t let go.

‘You shouldn’t let those girls get away with that.’

‘It’s fine. Really. Hardly ever happens.’

‘Liar.’ He smiles at me, and slowly I feel the muscles in my face soften.

I tug at the folder again. This time he releases it, but his fingers brush against mine. It startles me and I look back to see if anyone saw it. Around us, people move in all directions, some darting into classrooms, others hanging out in the hallway. No one is looking at us.

No one sees us.

No one sees me.

I take a deep breath and walk away.

When I look back, he’s still standing there.

My shoulder skims the corner of the wall, then I’m in a new hallway and I don’t see him anymore.

I’m not used to being at a mixed-gender school. Boys sitting beside girls in classes. The girls’ changing room next door to the boys’ changing room. Girls standing in front of or behind boys in the lunch queue. Boys eating with girls they barely know. Nobody else here thinks this is strange but me.

Room 17 is dark, having not been used for classes all day. It’s stuffy so one of the students cracks open a window. Cool clean air seeps in from the gap and I take a deep breath. The room is full. Classmates sit on desks, in chairs, lean against bookshelves. No one will notice me here.

I stand by the door in the back. The door handle jabs into my spine a little but I stay. This is the perfect spot. This is my spot. I stand here every week.

Some people take notes, while others hide their phones under the desks and text their friends. I don’t know why they come. Most won’t be applying to university and some won’t get in even if they do. I know why I come. Not because we’re obligated to sign up to one of the many UCAS sessions held throughout the school week. And not because I don’t know how to navigate the online system, or don’t know what universities are looking for in applicants. My grades are impeccable and I will certainly obtain unconditional offers for all the universities that I apply to. I could probably teach this class. In the second week, the instructor spent an hour walking us through how to complete the first page of the application form – ‘Personal Information’. I’m pretty confident we can all recall our full name, address, date of birth and a contact telephone number.

That’s not why I come here.

I wait until the lights dim, then watch as the instructor struggles to bring up the first slide of his PowerPoint presentation. Perfect time to slip out. No one turns. Anyone who does see me leave will probably just assume I’m going to the toilet and not question it.

The hallway is already quiet, even though it’s only been fifteen minutes since the last bell. Those girls are long gone now. They’re probably shopping for a new eyeliner in Boots on the way home, or picking up the new Glamour or InStyle from WHSmith. Sometimes I dislike them. Other times, I envy them. I don’t have that luxury of ‘free time’. Between waking up and going to sleep, my day is mapped out for me. What I wouldn’t give for one afternoon after school where I could stay out as late as I want, skip dinner with the family, skip my evening readings, skip everything. Maybe I could leave school early, fake a sore belly, and have hours to myself – hours to lose to nothing, to lose to everything. But time slips by me, never glancing back. Time bumps into me in the hallway, and sits too close to me in the cafeteria. Time sits behind me in class, and ticks against my wrist, reminding me that seconds are passing, but that they don’t belong to me. They belong to everyone else. They belong to those girls.

Time.

When I reach the top of the hill, I look down at the watch on my wrist and adjust the alarm. I have thirty-five minutes. A deep breath escapes my lips. A flutter in my belly. Heat in my cheeks.

Boys sitting beside girls.

Girls meeting boys.

I bite my lip, feel the pressure between the teeth build.

And then I see him, waiting for me on the hill. He turns. He sees me. Finally someone sees me.

Then there comes that smile.