Читать книгу Settler Colonialism, Race, and the Law - Natsu Taylor Saito - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

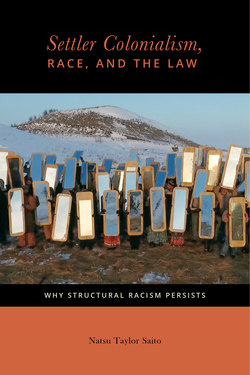

The Violence of Colonization

ОглавлениеThe lived realities of Indigenous peoples and others who, as a rule, have been excluded from the settler class are notably absent from the master narrative. While the specifics of their experiences differ widely, the most consistent shared theme may be the violence visited upon them as a means of achieving the colonizers’ objectives; a violence that always seems to be minimized, distorted, or erased by the silent spaces of the dominant narrative. This warrants emphasis as we think about social transformation because maintaining the status quo is almost inevitably portrayed as a nonviolent—usually, the nonviolent—option; the violence inherent to constructing and preserving that status quo is rarely acknowledged.

American history as disseminated through the popular media and public education generally provides a highly sanitized version of the exploitation of Indigenous peoples, persons of African descent, externally colonized peoples, and certain immigrant groups. As a result, the violence attending such exploitation becomes invisible. Thus, for example, American Indians are typically depicted as “inadvertently” being killed by disease or miraculously “vanishing.” When violence on the part of the colonizers is admitted at all, it is almost invariably characterized as individual or collective self-defense.63

The horrors of enslavement endured—and resisted—by African as well as American Indian peoples for several centuries are collapsed into a sidebar, the main story of slavery being the conflicts it engendered within the settler class and their eventual (triumphal) resolution. Several hundred years of slavery and economic exploitation, exclusions from citizenship or political participation, and legalized apartheid are depicted as passing phases in the gradual extension of democratic rights to White women and to people of color.64 To the extent that violence in the interest of racialized repression is admitted, the mainstream narrative relegates it to a past for which no one is today responsible.65 And the violence faced by people on a daily basis as a result of their (perceived) race, ethnicity, national origin, or religion is continuously dismissed as anomalous.66

The legitimacy of acquiring Indigenous lands in violation of treaties, by aggressive warfare, or through agreements with other colonial powers is never seriously questioned, for the narrative begins from the premise that the United States was divinely ordained to exist in its current form. The seizure of northern Mexico in 1848, the “purchase” of Alaska in 1868, the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i in 1893 and its subsequent annexation, the colonization of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines beginning in 1898—these are just color-coded building blocks on the map of US territorial expansion, evidence of the settlers’ “manifest destiny.”67 Neither the violence entailed in these invasions nor their consistently questionable legal rationales are acknowledged. In essence, all the United States’ wars have been “good” wars, enabling its territorial consolidation as well as its rise to global power and influence. The underlying realities cannot be interrogated for fear of exposing the conflict between the means used and the “ideals of justice, political representation, and opportunity” central to the settlers’ justification for the establishment and maintenance of “their” country.68

All of this is important to understanding where we are, collectively, and how we got here. But if we want to develop liberatory visions of the future, we will need to look beyond the silent spaces of the narrative that is being told to the narratives that are not being told. This means making the effort to understand what was here before the colonizers arrived and opening our minds to the fact that there are many perspectives from which the world around us, and all of our relationships, can be and is understood.