Читать книгу Settler Colonialism, Race, and the Law - Natsu Taylor Saito - Страница 46

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Looking Ahead

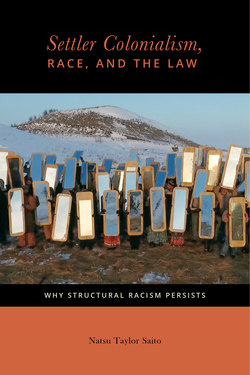

ОглавлениеBetween April 2016 and February 2017, some ten thousand water protectors gathered in prayer camps just north of the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota to contest construction of the Dakota Access oil pipeline.136 The pipeline, which now threatens the water supply of the Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Reservations, was initially slated to run slightly north of Bismarck, a city that is over 90 percent White, but the Army Corps of Engineers rejected this route because it would endanger the municipal water supply of a “high consequence area.”137 In an act described by the Reverend Jesse Jackson as “the ripest case of environmental racism I’ve seen in a long time,”138 the pipeline was rerouted through unceded lands in the Great Sioux Nation, as recognized by the 1851 and 1868 Fort Laramie treaties.139

The resistance camps were located where the pipeline would ultimately cross the Missouri, known as Inyan Makangapi Wakpa, the River That Makes Sacred Stones, because of whirlpools that created large sandstone spheres.140 Pointing out the historical significance of that land as well as the burial grounds and other sacred sites located along the river, LaDonna Bravebull Allard, who established the Sacred Stone camp in April 2016, explained:

This river holds the story of my entire life. . . . The US government is wiping out our most important cultural and spiritual areas. And as it erases our footprint from the world, it erases us as a people. These sites must be protected, or our world will end, it is that simple. . . . If we allow an oil company to dig through and destroy our histories, our ancestors, our hearts and souls as a people is that not genocide? . . . We are the river, and the river is us. We have no choice but to stand up.141

The local settler population had a very different perspective, of course, and their hostility toward the water protectors, and to American Indians generally, was palpable. In the surrounding, overwhelmingly White counties, residents received “reverse 911” calls to warn them about areas that were “unsafe” because prayer circles or demonstrations were occurring, and local businesses were encouraged to deny service to persons supporting the occupation.142 Prior to the trials of arrested water protectors, a National Jury Project survey found that well over three-quarters of the juror-eligible population was already convinced of the defendants’ guilt.143 The local White residents’ reactions reflected a deep-seated fear that the legitimacy of their presence on Indigenous lands was being questioned. “I’m the son of farmers, and we worked hard for everything we have,”144 a local sheriff’s deputy explained. In this simple statement, the deputy sheriff captured the essence of the settler narrative.

The state’s response to the nonviolent opposition manifest at Standing Rock reveals the extent to which American settler society will still go to ensure hegemonic control over its claimed territorial base. Responding to the North Dakota governor’s request for assistance in this “state of emergency,” counties and cities across ten states sent law enforcement personnel to help quash the resistance and clear the camps. In this process, the water protectors—men, women, children, and elders, often in prayer—were attacked with mace and dogs, concussion grenades, water cannons in subzero winter weather, and “less than lethal” weaponry.145 The violence deployed by a virtual army recruited from over seventy law enforcement and security agencies was severe enough to warrant quick condemnation by six United Nations special rapporteurs and other UN officials.146

Why would President Obama—who just months earlier had denounced police brutality as “an American issue” about which “all fair-minded people should be concerned”—decide to simply “let it play out” at Standing Rock?147 When confronted with anti-Indian racism, one senses a consciousness, or dis-ease, about who has a right to be on the land. Patrick Wolfe has described settler colonialism as “a winner-take-all project,”148 and it is clear that, from the settler perspective, the occupancy of North America continues to be an either/or proposition.

Ultimately over eight hundred water protectors were arrested and, in February 2017, the main camps were destroyed by heavily armed police units.149 Throughout the occupation, the pipeline owners also deployed private contractors from TigerSwan, a mercenary firm employed by the US government in global counterterrorism missions. A TigerSwan assessment, written after the water protectors had been removed, compared the water protectors to “jihadist insurgents” and concluded that “aggressive intelligence preparation of the battlefield and active coordination between intelligence and security elements are now a proven method of defeating pipeline insurgencies.”150 In a very literal sense, the “Indian Wars” are not over.

American Indians and other Indigenous peoples under the United States’ purported jurisdiction have not disappeared, but continue to survive and resist after more than five centuries of colonization. Currently, the federal government recognizes some 566 Indian nations,151 and about 5.4 million people, or 2 percent of the total population, identify as American Indian or Alaska Native, with almost half that number identifying exclusively as such.152 Nearly one-third of this population is under the age of eighteen, as compared to about a quarter of the population as a whole,153 indicating that the Indigenous population is rebounding, to some extent, from the sterilization programs and slow death measures imposed upon it over the past several generations. This does not mean, however, that settler society has come to terms with the fact of Indigenous existence. Instead, it continues to use every means available to it to deny, suppress, and subvert the sovereignty of Indigenous nations and their peoples’ right to self-determination.

Indigenous peoples’ claims to their traditional lands are consistently disregarded. This cannot be dismissed as “a phenomenon of the past” because, as law professor Joseph Singer observes, “the law continues to confer—and withhold—property rights in a way that provides less protection” for American Indian nations than non-Indian individuals or entities.154 Today, American Indian nations hold approximately fifty million acres of land—about 2 percent of the country’s continental land base155—but their control over even these lands and resources remains subject to the absolute, plenary power of the federal government. The meager revenues they generate are held “in trust” by the government, which has so grossly mismanaged them that it cannot account for perhaps $140 billion of individual Indian trust monies.156

American Indians and Alaska Natives, like African Americans, are approximately three times more likely to be killed by law enforcement officials than their White counterparts.157 They are subjected to violent assault, rape, and murder at levels that far exceed the general population, and have less police protection than other demographic groups.158 Today American Indians and Alaska Natives are the poorest “racial group” in the United States.159 They have higher rates of unemployment and incarceration than other demographic subgroups, less education, poorer health, and lower life expectancies, are subject to higher levels of violence on a daily basis, and have by far the highest suicide rate.160 These are conditions common to colonized peoples, and directly attributable to the strategies of dispossession and elimination by which the American settler state has appropriated and maintained control of its territorial base.

The continued colonization of the lands appropriated by the United States, and the concomitant dispossession of the peoples indigenous to those lands, is foundational to any analysis of, or attempt to address, racial injustice in America for at least two reasons. First, until underlying Indigenous claims are addressed, claims by other peoples to an “equal right” to the fruits of that colonization legitimize the genocidal policies and practices upon which the wealth of America is built. As Singer observes, “If those who benefit from this history of injustice claim a vested right to its benefits, they should be aware that what they claim is a right to the benefits of a system of racial hierarchy.”161

Second, other manifestations of racial hierarchy cannot be effectively dismantled until colonial occupation and appropriation are addressed. If land is the fundamental prerequisite of the settler colonial state, and the settlers’ claims to that land rest squarely—still—on the racialization of its original owners as savage and subhuman, those in power cannot, and will not, abandon hierarchical racialization within American society, for that would undermine the basis for the state’s claimed prerogative to defend its “territorial integrity.”162

This chapter has focused on the desire for land as the primary driving force of settler colonial societies and, therefore, has emphasized strategies employed to eliminate, or “disappear,” the original owners of the land. Historically, as the colonizers consolidated their territorial control, they enlisted labor to render “their” lands profitable, a process that, from the beginning, included the enslaved labor of both American Indian and African peoples. Enslaved Africans, of course, were also colonized Indigenous peoples, and many people ultimately classified as “Black” were of American Indian as well as African descent. But settler priorities were most effectively realized by eliminating as many American Indians as possible while encouraging the expansion of a subjugated Afrodescendant population. It is in this sense that Patrick Wolfe says “the two societies, Red and Black, were of antithetical but complementary value to White society.”163 “The outcome was a triangular transcontinental relationship in which the labour of enslaved Africans was mixed with the land of dispossessed Americans to produce European property.”164 This process and its contemporary consequences are the subjects of the next two chapters.