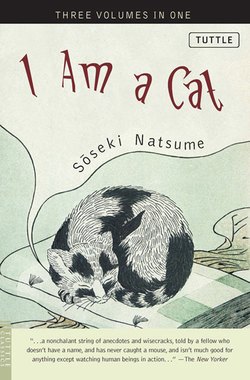

Читать книгу I Am A Cat - Natsume Soseki - Страница 8

ОглавлениеII

SINCE New Year’s Day I have acquired a certain modest celebrity: so that, though only a cat, I am feeling quietly proud of myself. Which is not unpleasing.

On the morning of New Year’s Day, my master received a picture-postcard, a card of New Year greetings from a certain painter-friend of his. The upper part was painted red, the lower deep green; and right in the center was a crouching animal painted in pastel. The master, sitting in his study, looked at this picture first one way up and then the other. “What fine coloring!” he observed. Having thus expressed his admiration, I thought he had finished with the matter. But no, he continued studying it, first sideways and then longways. In order to examine the object he twists his body, then stretches out his arms like an ancient studying the Book of Divinations and then, turning to face the window, he brings it in to the tip of his nose. I wish he would soon terminate this curious performance, for the action sets his knees away and I find it hard to keep my balance. When at long last the wobbling began to diminish, I heard him mutter in a tiny voice, “I wonder what it is.” Though full of admiration for the colors on the picture-postcard, he couldn’t identify the animal painted in its center. Which explained his extraordinary antics. Could it perhaps really be a picture more difficult to interpret than my own first glance had suggested? I half-opened my eyes and looked at the painting with an imperturbable calmness. There could be no shadow of a doubt: it was a portrait of myself. I do not suppose that the painter considered himself an Andrea del Sarto, as did my master; but, being a painter, what he had painted, both in respect of form and of color, was perfectly harmonious. Any fool could see it was a cat. And so skillfully painted that anyone with eyes in his head and the mangiest scrap of discernment would immediately recognize that it was a picture of no other cat but me. To think that anyone should need to go to such painful lengths over such a blatantly simple matter. . . I felt a little sorry for the human race. I would have liked to have let him know that the picture is of me. Even if it were too difficult for him to grasp that particularity, I would still have liked to help him see that the painting is of a cat. But since heaven has not seen fit to dower the human animal with an ability to understand cat language, I regret to say that I let the matter be.

Incidentally, I would like to take the occasion of this incident to advise my readers that the human habit of referring to me in a scornful tone of voice as some mere trifling “cat” is an extremely bad one. Humans appear to think that cows and horses are constructed from rejected human material, and that cats are constructed from cow pats and horse dung. Such thoughts, objectively regarded, are in very poor taste though they are no doubt not uncommon among teachers who, ignorant even of their ignorance, remain self-satisfied with their quaint puffed-up ideas of their own unreal importance. Even cats must not be treated roughly or taken for granted. To the casual observer it may appear that all cats are the same, facsimiles in form and substance, as indistinguishable as peas in a pod; and that no cat can lay claim to individuality. But once admitted to feline society, that casual observer would very quickly realize that things are not so simple, and that the human saying that “people are freaks” is equally true in the world of cats. Our eyes, noses, fur, paws—all of them differ. From the tilt of one’s whiskers to the set of one’s ears, down to the very hang of one’s tail, we cats are sharply differentiated. In our good looks and our poor looks, in our likes and dislikes, in our refinement and our coarsenesses, one may fairly say that cats occur in infinite variety. Despite the fact of such obvious differentiation, humans, their eyes turned up to heaven by reason of the elevation of their minds or some such other rubbish, fail to notice even obvious differences in our external features, that our characters might be characteristic is beyond their comprehension. Which is to be pitied. I understand and endorse the thought behind such sayings as, the cobbler should stick to his last, that birds of a feather flock together, that rice-cakes are for rice-cake makers. For cats, indeed, are for cats. And should you wish to learn about cats, only a cat can tell you. Humans, however advanced, can tell you nothing on this subject. And inasmuch as humans are, in fact, far less advanced than they fancy themselves, they will find it difficult even to start learning about cats. And for an unsympathetic man like my master there’s really no hope at all. He does not even understand that love can never grow unless there is at least a complete and mutual understanding. Like an ill-natured oyster, he secretes himself in his study and has never once opened his mouth to the outside world. And to see him there, looking as though he alone has truly attained enlightenment, is enough to make a cat laugh. The proof that he has not attained enlightenment is that, although he has my portrait under his nose, he shows no sign of comprehension but coolly offers such crazy comment as, “perhaps, this being the second year of the war against the Russians, it is a painting of a bear.”

As, with my eyes closed, I sat thinking these thoughts on my master’s knees, the servant-woman brought in a second picture-postcard. It is a printed picture of a line of four or five European cats all engaged in study, holding pens or reading books. One has broken away from the line to perform a simple Western dance at the corner of their common desk. Above this picture “I am a cat” is written thickly in Japanese black ink. And down the right-hand side there is even a haiku stating that “on spring days cats read books or dance.”The card is from one of the master’s old pupils and its meaning should be obvious to anyone. However my dimwitted master seems not to understand, for he looked puzzled and said to himself, “Can this be a Year of the Cat?” He just doesn’t seem to have grasped that these postcards are manifestations of my growing fame.

At that moment the servant brought in yet a third postcard. This time the postcard has no picture, but alongside the characters wishing my master a happy New Year, the correspondent has added those for, “Please be so kind as to give my best regards to the cat.” Bone-headed though he is, my master does appear to get the message when it’s written out thus unequivocally: for he glanced down at my face and, as if he really had at last comprehended the situation, said, “hmm.” And his glance, unlike his usual ones, did seem to contain a new modicum of respect. Which was quite right and proper considering the fact that it is entirely due to me that my master, hitherto a nobody, has suddenly begun to get a name and to attract attention.

Just then the gate-bell sounded: tinkle-tinkle, possibly even ting-ting. Probably a visitor. If so, the servant will answer. Since I never go out of my way to investigate callers, except the fishmonger’s errand-boy, I remained quietly on my master’s knees. The master, however, peered worriedly toward the entrance as if duns were at the door. I deduce that he just doesn’t like receiving New Year’s callers and sharing a convivial tot. What a marvellous way to be. How much further can pure bigotry go? If he doesn’t like visitors, he should have gone out himself, but he lacks even that much enterprise. The inaudacity of his clam-like character grows daily more apparent. A few moments later the servant comes in to say that Mr. Coldmoon has called. I understand that this Coldmoon person was also once a pupil of my master’s and that, after leaving school, he so rose in the world to be far better known than his teacher. I don’t know why, but this fellow often comes round for a chat. On every such visit he babbles on, with a dreadful sort of coquettishness, about being in love or not in love with somebody or other; about how much he enjoys life or how desperately he is tired of it. And then he leaves. It is quaint enough that to discuss such matters he should seek the company of a withered old nut like my master, but it’s quainter still to see my mollusk opening up to comment, now and again, on Coldmoon’s mawkish maunderings.

“I’m afraid I haven’t been round for quite some time. Actually, I’ve been as busy as, busy since the end of last year, and, though I’ve thought of going out often enough, somehow shanks’ pony has just not headed here.” Thus, twisting and untwisting the fastening-strings of his short surcoat, Coldmoon babbled on.

“Where then did shanks’ pony go?” my master enquired with a serious look as he tugged at the cuffs of his worn, black, crested surcoat. It is a cotton garment unduly short in the sleeves, and some of its nondescript, thin, silk lining sticks out about a half an inch at the cuffs.

“As it were in various directions,” Coldmoon answered, and then laughed. I notice that one of his front teeth is missing.

“What’s happened to your teeth?” asks my master, changing the subject.

“Well, actually, at a certain place I ate mushrooms.”

“What did you say you ate?”

“A bit of mushroom. As I tried to bite off a mushroom’s umbrella with my front teeth, a tooth just broke off.”

“Breaking teeth on a mushroom sounds somewhat senile. An image possibly appropriate to a haiku but scarcely appropriate to the pursuit of love,” remarked my master as he tapped lightly on my head with the palm of his hand.

“Ah! Is that the cat? But he’s quite plump! Sturdy as that, not even Rickshaw Blacky could beat him up. He certainly is a most splendid beast.” Coldmoon offers me his homage.

“He’s grown quite big lately,” responds my master, and proudly smacks me twice upon the head. I am flattered by the compliment but my head feels slightly sore.

“The night before last, what’s more, we had a little concert,” said Coldmoon going back to his story.

“Where?”

“Surely you don’t have to know where. But it was quite interesting, three violins to a piano accompaniment. However unskilled, when there are three of them, violins sound fairly good. Two of them were women and I managed to place myself between them. And I myself, I thought, played rather well.”

“Ah, and who were the women?” enviously my master asks. At first glance my master usually looks cold and hard; but, to tell the truth, he is by no means indifferent to women. He once read in a Western novel of a man who invariably fell partially in love with practically every woman that he met. Another character in the book somewhat sarcastically observed that, as a rough calculation, that fellow fell in love with just under seven-tenths of the women he passed in the street. On reading this, my master was struck by its essential truth and remained deeply impressed. Why should a man so impressionable lead such an oysterish existence? A mere cat such as I cannot possibly understand it. Some say it is the result of a love affair that went wrong; some say it is due to his weak stomach; while others simply state that it’s because he lacks both money and audacity. Whatever the truth, it doesn’t much matter since he’s a person of insufficient importance to affect the history of his period. What is certain is that he did enquire enviously about Coldmoon’s female fiddlers. Coldmoon, looking amused, picked up a sliver of boiled fishpaste in his chopsticks and nipped at it with his remaining front teeth. I was worried lest another should fall out. But this time it was all right.

“Well, both of them are daughters of good families. You don’t know them,” Coldmoon coldly answered.

The master drawled “Is—th-a-t—,” but omitted the final “so” which he’d intended.

Coldmoon probably considered it was about time to be off, for he said, “What marvellous weather. If you’ve nothing better to do, shall we go out for a walk? As a result of the fall of Port Arthur,” he added encouragingly, “the town’s unusually lively.”

My master, looking as though he would sooner discuss the identity of the female fiddlers than the fall of Port Arthur, hesitated for a moment’s thought. But he seemed finally to reach a decision, for he stood up resolutely and said, “All right, let’s go out.” He continues to wear his black cotton crested surcoat and, thereunder, a quilted kimono of hand-woven silk which, supposedly a keep-sake of his elder brother, he has worn continuously for twenty years. Even the most strongly woven silk, cannot survive such unremitting, such preternaturally, perennial wear. The material has been worn so thin that, held against the light, one can see the patches sewn on here and there from the inner side. My master wears the same clothes throughout December and January, not bothering to observe the traditional New Year change. He makes, indeed, no distinction between workaday and Sunday clothes. When he leaves the house he saunters out in whatever dress he happens to have on. I do not know whether this is because he has no other clothes to wear or whether, having such clothes, he finds it too much of a bore to change into them. Whatever the case, I can’t conceive that these uncouth habits are in any way connected with disappointment in love.

After the two men left, I took the liberty of eating such of the boiled fishpaste as Coldmoon had not already devoured. I am, these days, no longer just a common, old cat. I consider myself at least as good as those celebrated in the tales of Momokawa Joen or as that cat of Thomas Gray’s, which trawled for goldfish. Brawlers such as Rickshaw Blacky are now beneath my notice. I don’t suppose anyone will make a fuss if I sneak a bit of fishpaste. Besides, this habit of taking secret snacks between meals is by no means a purely feline custom. O-san, for instance, is always pinching cakes and things, which she gobbles down whenever the mistress leaves the house. Nor is O-san the only offender: even the children, of whose refined upbringing the mistress is continually bragging, display the selfsame tendency. Only a few days ago that precious pair woke at some ungodly hour, and, though their parents were still sound asleep, took it upon themselves to sit down, face-to-face, at the dining-table. Now it is my master’s habit every morning to consume most of a loaf of bread, and to give the children scraps thereof which they eat with a dusting of sugar. It so happened that on this day the sugar basin was already on the table, even a spoon stuck in it. Since there was no one there to dole them out their sugar, the elder child scooped up a spoonful and dumped it on her plate. The younger followed her elder’s fine example and spooned an equal pile of sugar onto another plate. For a brief while these charming creatures just sat and glared at each other. Then the elder girl scooped a second spoonful onto her plate, and the younger one proceeded to equalize the position. The elder sister took a third spoonful and the younger, in a splendid spirit of rivalry, followed suit. And so it went on until both plates were piled high with sugar and not one single grain remained in the basin. My master thereupon emerged from his bedroom rubbing half-sleepy eyes and proceeded to return the sugar, so laboriously extracted by his daughters, back into the sugar-basin. This incident suggests that, though egotistical egalitarianism may be more highly developed among humans than among cats, cats are the wiser creatures. My advice to the children would have been to lick the sugar up quickly before it became massed into such senseless pyramids, but, because they cannot understand what I say, I merely watched them in silence from my warm, morning place on top of the container for boiled rice.

My master came home late last night from his expedition with Coldmoon. God knows where he went, but it was already past nine before he sat down at the breakfast table. From my same old place I watched his morose consumption of a typical New Year’s breakfast of rice-cakes boiled with vegetables, all served up in soup. He takes endless helpings. Though the rice-cakes are admittedly small, he must have eaten some six or seven before leaving the last one floating in the bowl. “I’ll stop now,” he remarked and laid his chopsticks down. Should anyone else behave in such a spoilt manner, he could be relied upon to put his foot down: but, vain in the exercise of his petty authority as master of the house, he seems quite unconcerned by the sight of the corpse of a scorched rice-cake drowning in turbid soup. When his wife took taka-diastase from the back of a small cupboard and put it on the table, my master said, “I won’t take it, it does me no good.”

“But they say it’s very good after eating starchy things. I think you should take some.” His wife wants him to take it.

“Starchy or not, the stuff’s no good.” He remains stubborn.

“Really, you are a most capricious man,” the mistress mutters as though to herself.

“I’m not capricious, the medicine doesn’t work.”

“But until the other day you used to say it worked very well and you used to take it every day, didn’t you?”

“Yes, it did work until that other day, but it hasn’t worked since then,” an antithetical answer.

“If you continue in these inconsistencies, taking it one day and stopping it the next, however efficacious the medicine may be, it will never do you any good. Unless you try to be a little more patient, dyspepsia, unlike other illnesses, won’t get cured, will it?” and she turns to O-san who was serving at the table.

“Quite so, madam. Unless one takes it regularly, one cannot find out whether a medicine is a good one or a bad one.” O-san readily sides with the mistress.

“I don’t care. I don’t take it because I don’t take it. How can a mere woman understand such things? Keep quiet.”

“All right. I’m merely a woman,” she says pushing the taka-diastase toward him, quite determined to make him see he is beaten. My master stands up without saying a word and goes off into his study. His wife and servant exchange looks and giggle. If on such occasions I follow him and jump up onto his knees, experience tells me that I shall pay dearly for my folly. Accordingly, I go quietly round through the garden and hop up onto the veranda outside his study. I peeped through the slit between the paper sliding doors and found my master examining a book by somebody called Epictetus. If he could actually understand what he’s reading, then he would indeed be worthy of praise. But within five or six minutes he slams the book down on the table, which is just what I’d suspected. As I sat there watching him, he took out his diary and made the following entry.

Took a stroll with Coldmoon round Nezu, Ueno, Ikenohata and Kanda. At Ikenohata, geishas in formal spring kimono were playing battledore and shuttlecock in front of a house of assignation. Their clothes beautiful, but their faces extremely plain. It occurs to me that they resemble the cat at home.

I don’t see why he should single me out as an example of plain features. If I went to a barber and had my face shaved, I wouldn’t look much different from a human. But, there you are, humans are conceited and that’s the trouble with them.

As we turned at Hotan’s corner another geisha appeared. She was slim, well-shaped and her shoulders were most beautifully sloped. The way she wore her mauve kimono gave her a genuine elegance. “Sorry about last night, Gen-chan—I was so busy. . .” She laughed and one glimpsed white teeth. Her voice was so harsh, as harsh as that of a roving crow, that her otherwise fine appearance diminished in enchantment. So much so that I didn’t even bother to turn around to see what sort of person this Gen-chan was, but sauntered on toward Onarimachi with my hands tucked inside the breast-fold of my kimono. Coldmoon, however, seemed to have become a trifle fidgety.

There is nothing more difficult than understanding human mentality. My master’s present mental state is very far from clear; is he feeling angry or lighthearted, or simply seeking solace in the scribblings of some dead philosopher? One just can’t tell whether he’s mocking the world or yearning to be accepted into its frivolous company; whether he is getting furious over some piddling little matter or holding himself aloof from worldly things. Compared with such complexities, cats are truly simple. If we want to eat, we eat; if we want to sleep, we sleep; when we are angry, we are angry utterly; when we cry, we cry with all the desperation of extreme commitment to our grief. Thus we never keep things like diaries. For what would be the point? No doubt human beings like my two-faced master find it necessary to keep diaries in order to display in a darkened room that true character so assiduously hidden from the world. But among cats both our four main occupations (walking, standing, sitting, and lying down) and such incidental activities as excreting waste are pursued quite openly. We live our diaries, and consequently have no need to keep a daily record as a means of maintaining our real characters. Had I the time to keep a diary, I’d use that time to better effect; sleeping on the veranda.

We dined somewhere in Kanda. Because I allowed myself one or two cups of saké (which I had not tasted for quite a time), my stomach this morning feels extremely well. I conclude that the best remedy for a stomach ailment is saké at suppertime. Taka-diastase just won’t do. Whatever claims are made for it, it’s just no good. That which lacks effect will continue to lack effect.

Thus with his brush he smears the good name of taka-diastase. It is as though he quarreled with himself, and in this entry one can see a last flash of this morning’s ugly mood. Such entries are perhaps most characteristic of human mores.

The other day, Mr. X claimed that going without one’s breakfast helped the stomach. So I took no breakfast for two or three days but the only effect was to make my stomach grumble. Mr. Y strongly advised me to refrain from eating pickles. According to him, all disorders of the stomach originate in pickles. His thesis was that abstinence from pickles so dessicates the sources of all stomach trouble, that a complete cure must follow. For at least a week no pickle crossed my lips, but, since that banishment produced no noticeable effect, I have resumed consuming them. According to Mr. Z, the one true remedy is ventral massage. But no ordinary massage of the stomach would suffice. It must be massage in accordance with the old-world methods of the Minagawa School. Massaged thus once, or at most twice, the stomach would be rid of every ill. The wisest scholars, such as Yasui Sokuken, and the most resourceful heroes, such as Sakamoto Ryoma, all relied upon this treatment. So off I went to Kaminegishi for an immediate massage. But the methods used were of inordinate cruelty. They told me, for instance, that no good could be hoped for unless one’s bones were massaged; that it would be difficult properly to eradicate my troubles unless, at least once, my viscera were totally inverted. At all events, a single session reduced my body to the condition of cotton-wool and I felt as though I had become a lifelong sufferer from sleeping sickness. I never went there again. Once was more than enough. Then Mr. A assured me that one shouldn’t eat solids. So I spent a whole day drinking nothing but milk. My bowels gave forth heavy plopping noises as though they had been swamped, and I could not sleep all night. Mr. B states that exercising one’s intestines by diaphragmic breathing produces a naturally healthy stomach and he counsels me to follow his advice. And I did try. For a time. But it proved no good for it made my bowels queasy. Besides, though every now and again I strive with all my heart and soul to control my breathing with the diaphragm, in five or six minutes I forget to discipline my muscles. And if I concentrate on maintaining that discipline I get so midriff-minded that I can neither read nor write. Waverhouse, my aesthete friend, once found me thus breathing in pursuit of a naturally healthy stomach and, rather unkindly, urged me, as a man, to terminate my labor-pangs. So diaphragmic breathing is now also a thing of the past. Dr. C recommends a diet of buckwheat noodles. So buckwheat noodles it was, alternately in soup and served cold after boiling. It did nothing, except loosen my bowels. I have tried every possible means to cure my ancient ailment, but all of them are useless. But those three cups of saké which I drank last night with Coldmoon have certainly done some good. From now on, I will drink two or three cups each evening.

I doubt whether this saké treatment will be kept up very long. My master’s mind exhibits the same incessant changeability as can be seen in the eyes of cats. He has no sense of perseverance. It is, moreover, idiotic that, while he fills his diary with lamentation over his stomach troubles, he does his best to present a brave face to the world; to grin and bear it. The other day his scholar friend, Professor Whatnot, paid a visit and advanced the theory that it was at least arguable that every illness is the direct result of both ancestral and personal malefaction. He seemed to have studied the matter pretty deeply for the sequence of his logic was clear, consistent, and orderly. Altogether it was a fine theory. I am sorry to say that my master has neither the brain nor the erudition to rebut such theories. However, perhaps because he himself was actually suffering from stomach trouble, he felt obliged to make all sorts of face-saving excuses. He irrelevantly retorted, “Your theory is interesting, but are you aware that Carlyle was dyspeptic?” as if claiming that because Carlyle was dyspeptic his own dyspepsia was an intellectual honor. His friend replied, “It does not follow that because Carlyle was a dyspeptic, all dyspeptics are Carlyles.” My master, reprimanded, held his tongue, but the incident revealed his curious vanity. It’s all the more amusing when one recalls that he would probably prefer not to be dyspeptic, for just this morning he recorded in his diary an intention to take treatment by saké as from tonight. Now that I’ve come to think of it, his inordinate consumption of rice-cakes this morning must have been the effect of last night’s saké session with Coldmoon. I could have eaten those cakes myself.

Though I am a cat, I eat practically anything. Unlike Rickshaw Blacky, I lack the energy to go off raiding fishshops up distant alleys. Further, my social status is such that I cannot expect the luxury enjoyed by Tortoiseshell whose mistress teaches the idle rich to play on the two-stringed harp. Therefore I don’t, as others can, indulge myself in likes and dislikes. I eat small bits of bread left over by the children, and I lick the jam from bean-jam cakes. Pickles taste awful, but to broaden my experience I once tried a couple of slices of pickled radish. It’s a strange thing but once I’ve tried it, almost anything turns out edible. To say, “I don’t like that” or “I don’t like this” is mere extravagant willfulness, and a cat that lives in a teacher’s house should eschew such foolish remarks. According to my master, there was once a novelist whose name was Balzac and he lived in France. He was an extremely extravagant man. I do not mean an extravagant eater but that, being a novelist, he was extravagant in his writing. One day he was trying to find a suitable name for a character in the novel he was writing, but, for whatever reason, could not think of a name that pleased him. Just then one of his friends called by, and Balzac suggested they should go out for a walk. This friend had, of course, no idea why, still less that Balzac was determined to find the name he needed. Out on the streets, Balzac did nothing but stare at shop signboards, but still he couldn’t find a suitable name. He marched on endlessly, while his puzzled friend, still ignorant of the object of the expedition, tagged along behind him. Having fruitlessly explored Paris from morning till evening, they were on their way home when Balzac happened to notice a tailor’s signboard bearing the name “Marcus.” He clapped his hands. “This is it,” he shouted. “It just has to be this. Marcus is a good name, but with a Z in front of Marcus it becomes a perfect name. It has to be a Z. Z. Marcus is remarkably good. Names that I invent are never good. They sound unnatural however cleverly constructed. But now, at long, long last, I’ve got the name I like.” Balzac, extremely pleased with himself, was totally oblivious to the inconvenience he had caused his friend. It would seem unduly troublesome that one should have to spend a whole day trudging around Paris merely to find a name for a character in a novel. Extravagance of such enormity acquires a certain splendor, but folk like me, a cat kept by a clam-like introvert, cannot even envisage such inordinate behavior. That I should not much care what, so long as it’s edible, I eat is probably an inevitable result of my circumstances. Thus it was in no way as an expression of extravagance that I expressed just now my feeling of wishing to eat a rice-cake. I simply thought that I’d better eat while the chance offered, and I then remembered that the piece of rice-cake which my master had left in his breakfast bowl was possibly still in the kitchen. So round to the kitchen I went.

The rice-cake was stuck, just as I saw it this morning, at the bottom of the bowl and its color was still as I remembered it. I must confess that I’ve never previously tasted rice-cake. Yet, though I felt a shade uncertain, it looks quite good to eat. With a tentative front paw I rake at the green vegetables adhering to the rice-cake. My claws, having touched the outer part of the rice-cake, become sticky. I sniff at them and recognize the smell that can be smelt when rice stuck at the bottom of a cooking-pot is transferred into the boiled-rice container. I look around, wondering, “Shall I eat it, shall I not?” Fortunately, or unfortunately, there’s nobody about. O-san, with a face that shows no change between year end and the spring, is playing battledore and shuttlecock. The children in the inner room are singing something about a rabbit and a tortoise. If I am to eat this New Year speciality, now’s the moment. If I miss this chance I shall have to spend a whole, long year not knowing how a rice-cake tastes. At this point, though a mere cat, I perceived a truth: that golden opportunity makes all animals venture to do even those things they do not want to do. To tell the truth, I do not particularly want to eat the rice-cake. In fact the more I examined the thing at the bottom of the bowl the more nervous I became and the more keenly disinclined to eat it. If only O-san would open the kitchen door, or if I could hear the children’s footsteps coming toward me, I would unhesitatingly abandon the bowl; not only that, I would have put away all thought of rice-cakes for another year. But no one comes. I’ve hesitated long enough. Still no one comes. I feel as if someone were hotly urging me on, someone whispering, “Eat it, quickly!” I looked into the bowl and prayed that someone would appear. But no one did. I shall have to eat the rice-cake after all. In the end, lowering the entire weight of my body into the bottom of the bowl, I bit about an inch deep into a corner of the rice-cake.

Most things that I bite that hard come clean off in my mouth. But what a surprise! For I found when I tried to reopen my jaw that it would not budge. I try once again to bite my way free, but find I’m stuck. Too late I realize that the rice-cake is a fiend. When a man who has fallen into a marsh struggles to escape, the more he thrashes about trying to extract his legs, the deeper in he sinks. Just so, the harder I clamp my jaws, the more my mouth grows heavy and my teeth immobilized. I can feel the resistance to my teeth, but that’s all. I cannot dispose of it. Waverhouse, the aesthete, once described my master as an aliquant man and I must say it’s rather a good description. This rice-cake too, like my master, is aliquant. It looked to me that, however much I continued biting, nothing could ever result: the process could go on and on eternally like the division of ten by three. In the middle of this anguish I found my second truth: that all animals can tell by instinct what is or is not good for them. Although I have now discovered two great truths, I remain unhappy by reason of the adherent rice-cake. My teeth are being sucked into its body, and are becoming excruciatingly painful. Unless I can complete my bite and run away quickly, O-san will be on me. The children seem to have stopped singing, and I’m sure they’ll soon come running into the kitchen. In an extremity of anguish, I lashed about with my tail, but to no effect. I made my ears stand up and then lie flat, but this didn’t help either. Come to think of it, my ears and tail have nothing to do with the rice-cake. In short, I had indulged in a waste of wagging, a waste of ear-erection, and a waste of ear-flattening. So I stopped.

At long last it dawned on me that the best thing to do is to force the rice-cake down by using my two front paws. First I raised my right paw and stroked it around my mouth. Naturally, this mere stroking brought no relief whatsoever. Next, I stretched out my left paw and with it scraped quick circles around my mouth. These ineffectual passes failed to exorcize the fiend in the rice-cake. Realizing that it was essential to proceed with patience, I scraped alternatively with my right and left paws, but my teeth stayed stuck in the rice-cake. Growing impatient, I now used both front paws simultaneously. Then, only then, I found to my amazement that I could actually stand up on my hind legs. Somehow I feel un-catlike. But not caring whether I am a cat or not, I scratch away like mad at my whole face in frenzied determination to keep on scratching until the fiend in the rice-cake has been driven out. Since the movements of my front paws are so vigorous I am in danger of losing my balance and falling down. To keep my equilibrium I find myself marking time with my hind legs. I begin to tittup from one spot to another, and I finish up prancing madly all over the kitchen. It gives me great pride to realize that I can so dextrously maintain an upright position, and the revelation of a third great truth is thus vouchsafed me: that in conditions of exceptional danger one can surpass one’s normal level of achievement. This is the real meaning of Special Providence.

Sustained by Special Providence, I am fighting for dear life against that demonic rice-cake when I hear footsteps. Someone seems to be approaching. Thinking it would be fatal to be caught in this predicament, I redouble my efforts and am positively running around the kitchen. The footsteps come closer and closer. Alas, that Special Providence seems not to last forever. In the end I am discovered by the children who loudly shout, “Why look! The cat’s been eating rice-cakes and is dancing.” The first to hear their announcement was that O-san person. Abandoning her shuttlecock and battledore, she flew in through the kitchen door crying, “Gracious me!” Then the mistress, sedate in her formal silk kimono, deigns to remark, “What a naughty cat.” And my master, drawn from his study by the general hubbub, shouts, “You fool!” The children find me funniest, but by general agreement the whole household is having a good old laugh. It is annoying, it is painful, it is impossible to stop dancing. Hell and damnation! When at long last the laughter began to die down, the dear, little five-year-old piped up with an, “Oh what a comical cat,” which had the effect of renewing the tide of their ebbing laughter. They fairly split their sides. I have already heard and seen quite a lot of heartless human behavior, but never before have I felt so bitterly critical of their conduct. Special Providence having vanished into thin air, I was back in my customary position on all fours, finally at my wit’s end, and, by reason of giddiness, cutting a quite ridiculous figure. My master seems to have felt it would be perhaps a pity to let me die before his very eyes, for he said to O-san, “Help him get rid of that rice-cake.” O-san looks at the mistress as if to say, “Why not make him go on dancing?” The mistress would gladly see my minuet continued, but, since she would not go so far as wanting me to dance myself to death, says nothing. My master turned somewhat sharply to the servant and ordered, “Hurry it up, if you don’t help quickly the cat will be dead.” O-san, with a vacant look on her face, as though she had been roughly wakened from some peculiarly delicious dream, took a firm grip on the rice-cake and yanked it out of my mouth. I am not quite as feeble-fanged as Coldmoon, but I really did think my entire front toothwork was about to break off. The pain was indescribable. The teeth embedded in the rice-cake are being pitilessly wrenched. You can’t imagine what it was like. It was then that the fourth enlightenment burst upon me: that all comfort is achieved through hardship. When at last I came to myself and looked around at a world restored to normality, all the members of the household had disappeared into the inner room.

Having made such a fool of myself, I feel quite unable to face such hostile critics as O-san. It would, I think, unhinge my mind. To restore my mental tranquillity, I decided to visit Tortoiseshell, so I left the kitchen and set off through the backyard to the house of the two-stringed harp. Tortoiseshell is a celebrated beauty in our district. Though I am undoubtedly a cat, I possess a wide general knowledge of the nature of compassion and am deeply sensitive to affection, kind-heartedness, tenderness, and love. Merely to observe the bitterness in my master’s face, just to be snubbed by O-san, leaves me out of sorts. At such times I visit this fair, lady friend of mine and our conversation ranges over many things. Then, before I am aware of it, I find myself refreshed. I forget my worries, hardships, everything. I feel as if reborn. Female influence is indeed a most potent thing. Through a gap in the cedar-hedge, I peer to see if she is anywhere about. Tortoiseshell, wearing a smart new collar in celebration of the season, is sitting very neatly on her veranda. The rondure of her back is indescribably beautiful. It is the most beautiful of all curved lines. The way her tail curves, the way she folds her legs, the charmingly lazy shake of her ears—all these are quite beyond description. She looks so warm sitting there so gracefully in the very sunniest spot. Her body holds an attitude of utter stillness and correctness. And her fur, glossy as velvet that reflects the rays of spring, seems suddenly to quiver although the air is still. For a while I stood, completely enraptured, gazing at her. Then as I came to myself, I softly called, “Miss Tortoiseshell, Miss Tortoiseshell,” and beckoned with my paw.

“Why, Professor,” she greeted me as she stepped down from the veranda. A tiny bell attached to her scarlet collar made little tinkling sounds. I say to myself, “Ah, it’s for the New Year that she’s wearing a bell,” and, while I am still admiring its lively tinkle, find she has arrived beside me. “A happy NewYear, Professor,” and she waves her tail to the left; for when cats exchange greetings one first holds one’s tail upright like a pole, then twists it round to the left. In our neighborhood it is only Tortoiseshell who calls me Professor. Now, I have already mentioned that I have, as yet, no name; it is Tortoiseshell, and she alone, who pays me the respect due to one that lives in a teacher’s house. Indeed, I am not altogether displeased to be addressed as a Professor, and respond willingly to her apostrophe.

“And a happy New Year to you,” I say. “How beautifully you’re done up!”

“Yes, the mistress bought it for me at the end of last year. Isn’t it nice?” and she makes it tinkle for me.

“Yes indeed, it has a lovely sound. I’ve never seen such a wonderful thing in my life.”

“No! Everyone’s using them,” and she tinkle-tinkles. “But isn’t it a lovely sound? I’m so happy.” She tinkle-tinkle-tinkles continuously.

“I can see your mistress loves you very dearly.” Comparing my lot with hers, I hinted at my envy of a pampered life.

Tortoiseshell is a simple creature. “Yes,” she says, “that’s true; she treats me as if I were her own child.” And she laughs innocently. It is not true that cats never laugh. Human beings are mistaken in their belief that only they are capable of laughter. When I laugh my nostrils grow triangular and my Adam’s apple trembles. No wonder human beings fail to understand it.

“What is your master really like?”

“My master? That sounds strange. Mine is a mistress. A mistress of the two stringed harp.”

“I know that. But what is her background? I imagine she’s a person of high birth?”

“Ah, yes.”

A small Princess-pine

While waiting for you. . .

Beyond the sliding paper-door the mistress begins to play on her two-stringed harp.

“Isn’t that a splendid voice?” Tortoiseshell is proud of it.

“It seems extremely good, but I don’t understand what she’s singing. What’s the name of the piece?”

“That? Oh, it’s called something or other. The mistress is especially fond of it. D’you know, she’s actually sixty-two? But in excellent condition, don’t you think?”

I suppose one has to admit that she’s in excellent condition if she’s still alive at sixty-two. So I answered, “Yes.” I thought to myself that I’d given a silly answer, but I could do no other since I couldn’t think of anything brighter to say.

“You may not think so, but she used to be a person of high standing. She always tells me so.”

“What was she originally?”

“I understand that she’s the thirteenth Shogun’s widowed wife’s private-secretary’s younger sister’s husband’s mother’s nephew’s daughter.”

“What?”

“The thirteenth Shogun’s widowed wife’s private-secretary’s younger sister’s. . .”

“Ah! But, please, not quite so fast. The thirteenth Shogun’s widowed wife’s younger sister’s private-secretary’s . . .”

“No, no, no. The thirteenth Shogun’s widowed wife’s private-secretary’s younger sister’s. . .”

“The thirteenth Shogun’s widowed wife’s. . .”

“Right.”

“Private-secretary’s. Right?”

“Right.”

“Husband’s. . .”

“No, younger sister’s husband’s.”

“Of course. How could I? Younger sister’s husband’s. . .”

“Mother’s nephew’s daughter. There you are.”

“Mother’s nephew’s daughter?”

“Yes, you’ve got it.”

“Not really. It’s so terribly involved that I still can’t get the hang of it.

What exactly is her relation to the thirteenth Shogun’s widowed wife?”

“Oh, but you are so stupid! I’ve just been telling you what she is. She’s the thirteenth Shogun’s widowed wife’s private-secretary’s younger sister’s husband’s mother’s. . .”

“That much I’ve followed, but. . .”

“Then, you’ve got it, haven’t you?”

“Yes.” I had to give in. There are times for little white lies.

Beyond the sliding paper-door the sound of the two-stringed harp came to a sudden stop and the mistress’ voice called, “Tortoiseshell, Tortoiseshell, your lunch is ready.” Tortoiseshell looked happy and remarked, “There, she’s calling, so I must go home. I hope you’ll forgive me?” What would be the good of my saying that I mind? “Come and see me again,” she said; and she ran off through the garden tinkling her bell. But suddenly she turned and came back to ask me anxiously, “You’re looking far from well. Is anything wrong?” I couldn’t very well tell her that I’d eaten a rice-cake and gone dancing; so, “No,” I said, “nothing in particular. I did some weighty thinking, which brought on something of a headache. Indeed I called today because I fancied that just to talk with you would help me to feel better.”

“Really? Well, take good care of yourself. Good-bye now.” She seemed a tiny bit sorry to leave me, which has completely restored me to the liveliness I’d felt before the rice-cake bit me. I now felt wonderful and decided to go home through that tea-plantation where one could have the pleasure of treading down lumps of half-melted frost. I put my face through the broken bamboo hedge, and there was Rickshaw Blacky, back again on the dry chrysanthemums, yawning his spine into a high, black arch. Nowadays I’m no longer scared of Blacky, but, since any conversation with him involves the risk of trouble, I endeavor to pass, cutting him off. But it’s not in Blacky’s nature to contain his feelings if he believes himself looked down upon. “Hey you, Mr. No-name. You’re very stuck-up these days, now aren’t you? You may be living in a teacher’s house, but don’t go giving yourself such airs. And stop, I warn you, trying to make a fool of me.” Blacky doesn’t seem to know that I am now a celebrity. I wish I could explain the situation to him, but, since he’s not the kind who can understand such things, I decide simply to offer him the briefest of greetings and then to take my leave as soon as I decently can.

“A happy New Year, Mr. Blacky. You do look well, as usual.” And I lift up my tail and twist it to the left. Blacky, keeping his tail straight up, refused to return my salutation.

“What! Happy? If the New Year’s happy, then you should be out of your tiny mind the whole year round. Now push off sharp, you back-end of a bellows.”

That turn of phrase about the back-end of a bellows sounds distinctly derogatory, but its semantic content happened to escape me. “What,” I enquired, “do you mean by the back-end of a bellows?”

“You’re being sworn at and you stand there asking its meaning. I give up! I really do! You really are a New Year’s nit.”

A New Year’s nit sounds somewhat poetic, but its meaning is even more obscure than that bit about the bellows. I would have liked to ask the meaning for my future reference, but, as it was obvious I’d get no clear answer, I just stood facing him without a word. I was actually feeling rather awkward, but just then the wife of Blacky’s master suddenly screamed out, “Where in hell is that cut of salmon I left here on the shelf? My God, I do declare that hellcat’s been here and snitched it once again! That’s the nastiest cat I’ve ever seen. See what he’ll get when he comes back!” Her raucous voice unceremoniously shakes the mild air of the season, vulgarizing its natural peacefulness. Blacky puts on an impudent look as if to say, “If you want to scream your head off, scream away,” and he jerked his square chin forward at me as if to say, “Did you hear that hullaballoo?” Up to this point I’ve been too busy talking to Blacky to notice or think about anything else; but now, glancing down, I see between his legs a mud-covered bone from the cheapest cut of salmon.

“So you’ve been at it again!” Forgetting our recent exchanges, I offered Blacky my usual flattering exclamation. But it was not enough to restore him to good humor.

“Been at it! What the hell d’you mean, you saucy blockhead? And what do you mean by saying ‘again’ when this is nothing but a skinny slice of the cheapest fish? Don’t you know who I am! I’m Rickshaw Blacky, damn you.” And, having no shirtsleeves to roll up, he lifts an aggressive right front-paw as high as his shoulder.

“I’ve always known you were Mr. Rickshaw Blacky.”

“If you knew, why the hell did you say I’d been at it again? Answer me!” And he blows out over me great gusts of oven breath. Were we humans, I would be shaken by the collar of my coat. I am somewhat taken aback and am indeed wondering how to get out of the situation, when that woman’s fearful voice is heard again.

“Hey! Mr. Westbrook. You there, Westbrook, can you hear me? Listen, I got something to say. Bring me a pound of beef, and quick. O.K.? Understand? Beef that isn’t tough. A pound of it. See?” Her beef-demanding tones shatter the peace of the whole neighborhood.

“It’s only once a year she orders beef and that’s why she shouts so loud. She wants the entire neighborhood to know about her marvellous pound of beef. What can one do with a woman like that!” asked Blacky jeeringly as he stretched all four of his legs. As I can find nothing to say in reply, I keep silent and watch.

“A miserable pound just simply will not do. But I reckon it can’t be helped. Hang on to that beef. I’ll have it later.” Blacky communes with himself as though the beef had been ordered specially for him.

“This time you’re in for a real treat. That’s wonderful!” With these words I’d hoped to pack him off to his home.

But Blacky snarled, “That’s nothing to do with you. Just shut your big mouth, you!” and using his strong hind-legs, he suddenly scrabbles up a torrent of fallen icicles which thuds down on my head. I was taken completely aback, and, while I was still busy shaking the muddy debris off my body, Blacky slid off through the hedge and disappeared. Presumably to possess himself of Westbrook’s beef.

When I get home I find the place unusually springlike and even the master is laughing gaily. Wondering why, I hopped onto the veranda, and, as I padded to sit beside the master, noticed an unfamiliar guest. His hair is parted neatly and he wears a crested cotton surcoat and a duck-cloth hakama. He looks like a student and, at that, an extremely serious one. Lying on the corner of my master’s small hand-warming brazier, right beside the lacquer cigarette-box, there’s a visiting card on which is written, “To introduce Mr. Beauchamp Blowlamp: from Coldmoon.” Which tells me both the name of this guest and the fact that he’s a friend of Coldmoon. The conversation going on between host and guest sounds enigmatic because I missed the start of it. But I gather that it has something to do with Waverhouse, the aesthete whom I have had previous occasion to mention.

“And he urged me to come along with him because it would involve an ingenious idea, he said.” The guest is talking calmly.

“Do you mean there was some ingenious idea involved in lunching at aWestern style restaurant?” My master pours more tea for the guest and pushes the cup toward him.

“Well, at the time I did not understand what this ingenious idea could be, but, since it was his idea, I thought it bound to be something interesting and. . .”

“So you accompanied him. I see.”

“Yes, but I got a surprise.”

The master, looking as if to say, “I told you so,” gives me a whack on the head. Which hurts a little. “I expect it proved somewhat farcical. He’s rather that way inclined.” Clearly, he has suddenly remembered that business with Andrea del Sarto.

“Ah yes? Well, as he suggested we would be eating something special. . .”

“What did you have?”

“First of all, while studying the menu, he gave me all sorts of information about food.”

“Before ordering any?”

“Yes.”

“And then?”

“And then, turning to a waiter, he said, ‘There doesn’t seem to be anything special on the card.’ The waiter, not to be outdone, suggested roast duck or veal chops. Whereupon Waverhouse remarked quite sharply that we hadn’t come a very considerable distance just for common or garden fare. The waiter, who didn’t understand the significance of common or garden, looked puzzled and said nothing.”

“So I would imagine.”

“Then, turning to me, Waverhouse observed that in France or in England one can obtain any amount of dishes cooked à la Tenmei or à la Manyō but that in Japan, wherever you go, the food is all so stereotyped that one doesn’t even feel tempted to enter a restaurant of the so-called Western style. And so on and so on. He was in tremendous form. But has he ever been abroad?”

“Waverhouse abroad? Of course not. He’s got the money and the time. If he wanted to, he could go off anytime. He probably just converted his future intention to travel into the past tense of widely traveled experience as a sort of joke.” The master flatters himself that he has said something witty and laughs invitingly. His guest looks largely unimpressed.

“I see. I wondered when he’d been abroad. I took everything he said quite seriously. Besides, he described such things as snail soup and stewed frogs as though he’d really seen them with his own two eyes.”

“He must have heard about them from someone. He’s adept at such terminological inexactitudes.”

“So it would seem,” and Beauchamp stares down at the narcissus in a vase. He seems a little disappointed.

“So, that then was his ingenious idea, I take it?” asks the master still in quest of certainties.

“No, that was only the beginning. The main part’s still to come.”

“Ah!”The master utters an interjection mingled with curiosity.

“Having finished his dissertation on matters gastronomical and European, he proposed ‘since it’s quite impossible to obtain snails or frogs, however much we may desire them, let’s at least have moat-bells. What do you say?’ And without really giving the matter any thought at all, I answered, ‘Yes, that would be fine.’”

“Moat-bells sound a little odd.”

“Yes, very odd, but because Waverhouse was speaking so seriously, I didn’t then notice the oddity.” He seems to be apologizing to my master for his carelessness.

“What happened next?” asks my master quite indifferently and without any sign of sympathetic response to his guest’s implied apology.

“Well, then he told the waiter to bring moat-bells for two. The waiter said,‘Do you mean meatballs, sir?’ but Waverhouse, assuming an ever more serious expression, corrected him with gravity. ‘No, not meatballs, moat-bells.’”

“Really? But is there any such dish as moat-bells?”

“Well I thought it sounded somewhat strange, but as Waverhouse was so calmly sure and is so great an authority on all things Occidental—remember it was then my firm belief that he was widely traveled—I too joined in and explained to the waiter,‘Moat-bells, my good man, moat-bells.’”

“What did the waiter do?”

“The waiter—it’s really rather funny now one comes to think back on it—looked thoughtful for a while and then said, ‘I’m terribly sorry sir, but today, unfortunately, we have no moat-bells. Though should you care for meatballs we could serve you, sir, immediately.’ Waverhouse thereupon looked extremely put out and said, ‘So we’ve come all this long way for nothing. Couldn’t you really manage moat-bells? Please do see what can be done,’ and he slipped a small tip to the waiter. The waiter said he would ask the cook again and went off into the kitchen.”

“He must have had his mind dead set on eating moat-bells.”

“After a brief interval the waiter returned to say that if moat-bells were ordered specially they could be provided, but that it would take a long time. Waverhouse was quite composed. He said, ‘It’s the New Year and we are in no kind of hurry. So let’s wait for it?’ He drew a cigar from the inside of his Western suit and lighted up in the most leisurely manner. I felt called upon to match his cool composure so, taking the Japan News from my kimono pocket, I started reading it. The waiter retired for further consultations.”

“What a business!” My master leans forward, showing quite as much enthusiasm as he does when reading war news in the dailies.

“The waiter re-emerged with apologies and the confession that, of late, the ingredients of moat-bells were in such short supply that one could not get them at Kameya’s nor even down at No. 15 in Yokohama.

He expressed regret, but it seemed certain that the material for moat-bells would not be back in stock for some considerable time. Waverhouse then turned to me and repeated, over and over again, ‘What a pity, and we came especially for that dish.’ I felt that I had to say something, so I joined him in saying,‘Yes, it’s a terrible shame! Really, a great, great pity!’”

“Quite so,” agrees my master, though I myself don’t follow his reasoning.

“These observations must have made the waiter feel quite sorry, for he said,‘When, one of these days, we do have the necessary ingredients, we’d be happy if you would come, sir, and sample our fare.’ But when Waverhouse proceeded to ask him what ingredients the restaurant did use, the waiter just laughed and gave no answer. Waverhouse then pressingly enquired if the key-ingredient happened to be Tochian (who, as you know, is a haiku poet of the Nihon School); and d’you know, the waiter answered,‘Yes, it is, sir, and that is precisely why none is currently available even in Yokohama. I am indeed,’ he added, ‘most regretful, sir.’”

“Ha-ha-ha! So that’s the point of the story? How very funny!” and the master, quite unlike his usual self, roars with laughter. His knees shake so much that I nearly tumble off. Paying no regard to my predicament, the master laughs and laughs. He seems suddenly deeply pleased to realize that he is not alone in being gulled by Andrea del Sarto.

“And then, as soon as we were out in the street, he said ‘You see, we’ve done well. That ploy about the moat-bells was really rather good, wasn’t it?’ and he looked as pleased as punch. I let it be known that I was lost in admiration, and so we parted. However, since by then it was well past the lunch-hour, I was nearly starving.”

“That must have been very trying for you.” My master shows, for the first time, a sympathy to which I have no objection. For a while there was a pause in the conversation and my purring could be heard by host and guest.

Mr. Beauchamp drains his cup of tea, now quite cold, in one quick gulp and with some formality remarks, “As a matter-of-fact I’ve come today to ask a favor from you.”

“Yes? And what can I do for you?” My master, too, assumes a formal face.

“As you know, I am a devotee of literature and art. . .”

“That’s a good thing,” replies my master quite encouragingly.

“Since a little while back, I and a few like-minded friends have got together and organized a reading group. The idea is to meet once a month for the purpose of continued studying in this field. In fact, we’ve already had the first meeting at the end of last year.”

“May I ask you a question? When you say, like that, a reading group, it suggests that you engage in reading poetry and prose in a singsong tone. But in what sort of manner do you, in fact, proceed?”

“Well, we are beginning with ancient works but we intend to consider the works of our fellow members.”

“When you speak of ancient works, do you mean something like Po Chu-i’s Lute Song?”

“No.”

“Perhaps things like Buson’s mixture of haiku and Chinese verse?”

“No.”

“What kinds of thing do you then do?”

“The other day, we did one of Chikamatsu’s lovers’ suicides.”

“Chikamatsu? You mean the Chikamatsu who wrote jōruri plays?” There are not two Chikamatsus. When one says Chikamatsu, one does indeed mean Chikamatsu the playwright and could mean nobody else. I thought my master really stupid to ask so fool a question. However, oblivious to my natural reactions, he gently strokes my head. I calmly let him go on stroking me, justifying my compliance with the reflection that so small a weakness is permissible when there are those in the world who admit to thinking themselves under loving observation by persons who merely happen to be cross-eyed.

Beauchamp answers, “Yes,” and tries to read the reaction on my master’s face.

“Then is it one person who reads or do you allot parts among you?”

“We allot parts and each reads out the appropriate dialogue. The idea is to empathize with the characters in the play and, above all, to bring out their individual personalities. We do gestures as well. The main thing is to catch the essential character of the era of the play. Accordingly, the lines are read out as if spoken by each character, which may perhaps be a young lady or possibly an errand-boy.”

“In that case it must be like a play.”

“Yes, almost the only things missing are the costumes and the scenery.”

“May I ask if your reading was a success?”

“For a first attempt, I think one might claim that it was, if anything, a success.”

“And which lovers’ suicide play did you perform on the last occasion?”

“We did a scene in which a boatman takes a fare to the red light quarter of Yoshiwara.”

“You certainly picked on a most irregular incident, didn’t you?” My master, being a teacher, tilts his head a little sideways as if regarding something slightly doubtful. The cigarette smoke drifting from his nose passes up by his ear and along the side of his head.

“No, it isn’t that irregular. The characters are a passenger, a boatman, a high-class prostitute, a serving-girl, an ancient crone of a brothel-attendant, and, of course, a geisha-registrar. But that’s all.” Beauchamp seems utterly unperturbed. My master, on hearing the words “a high-class prostitute,” winces slightly but probably only because he’s not well up in the meanings of such technical terms as nakai, yarite, and kemban. He seeks to clear the ground with a question. “Does not nakai signify something like a maid-servant in a brothel?”

“Though I have not yet given the matter my full attention, I believe that nakai signifies a serving-girl in a teahouse and that yarite is some sort of an assistant in the women’s quarters.” Although Beauchamp recently claimed that his group seeks to impersonate the actual voices of the characters in the plays, he does not seem to have fully grasped the real nature of yarite and nakai.

“I see, nakai belong to a teahouse while yarite live in a brothel. Next, are kemban human beings or is it the name of a place? If human, are they men or women?”

“Kemban, I rather think, is a male human being.”

“What is his function?”

“I’ve not yet studied that far. But I’ll make inquiries, one of these days.”

Thinking, in the light of these revelations, that the play-readings must be affairs extraordinarily ill-conducted, I glance up at my master’s face.

Surprisingly, I find him looking serious. “Apart from yourself, who were the other readers taking part?”

“A wide variety of people. Mr. K, a Bachelor of Law, played the high-class prostitute, but his delivery of that woman’s sugary dialogue through his very male mustache did, I confess, create a slightly queer impression. And then there was a scene in which this oiran was seized with spasms. . .”

“Do your readers extend their reading activities to the simulation of spasms?” asked my master anxiously.

“Yes indeed; for expression is, after all, important.” Beauchamp clearly considers himself a literary artist à l’outrance.

“Did he manage to have his spasms nicely?” My master has made a witty remark.

“The spasms were perhaps the only thing beyond our capability at such a first endeavor.” Beauchamp, too, is capable of wit.

“By the way,” asks my master, “what part did you take?”

“I was the boatman.”

“Really? You, the boatman!” My master’s tone was such as to suggest that, if Beauchamp could be a boatman, he himself could be a geisha-registrar. Switching his tone to one of simple candor, he then asks: “Was the role of the boatman too much for you?”

Beauchamp does not seem particularly offended. Maintaining the same calm voice, he replies, “As a matter of fact, it was because of this boatman that our precious gathering, though it went up like a rocket, came down like a stick. It so happened that four or five girl students are living in the boarding house next door to our meeting hall. I don’t know how, but they found out when our reading was to take place. Anyway, it appears that they came and listened to us under the window of the hall. I was doing the boatman’s voice, and, just when I had warmed up nicely and was really getting into the swing of it—perhaps my gestures were a little over-exaggerated—the girl students, all of whom had managed to control their feelings up to that point, thereupon burst out into simultaneous cachinnations. I was of course surprised, and I was of course embarrassed: indeed, thus dampened, I could not find it in me to continue. So our meeting came to an end.”

If this were considered a success, even for a first meeting, what would failure have been like? I could not help laughing. Involuntarily, my Adam’s apple made a rumbling noise. My master, who likes what he takes to be purring, strokes my head ever more and more gently. I’m thankful to be loved just because I laugh at someone, but at the same time I feel a bit uneasy.

“What very bad luck!” My master offers condolences despite the fact that we are still in the congratulatory season of the New Year.

“As for our second meeting, we intend to make a great advance and manage things in the grand style. That, in fact, is the very reason for my call today: we’d like you to join our group and help us.”

“I can’t possibly have spasms.” My negative-minded master is already poised to refuse.

“No, you don’t have to have spasms or anything like that. Here’s a list of the patron members.” So saying, Beauchamp very carefully produced a small notebook from a purple-colour carrying-wrapper. He opened the notebook and placed it in front of my master’s knees. “Will you please sign and make your seal-mark here?” I see that the book contains the names of distinguished Doctors of Literature and Bachelors of Arts of this present day, all neatly mustered in full force.

“Well, I wouldn’t say I object to becoming a supporter, but what sort of obligations would I have to meet?” My oyster-like master displays his apprehensions. . .

“There’s hardly any obligation. We ask nothing from you except a signature expressing your approval.”

“Well, in that case, I’ll join.” As he realizes that there is no real obligation involved, he suddenly becomes lighthearted. His face assumes the expression of one who would sign even a secret commitment to engage in rebellion, provided it was clear that the signature carried no binding obligation. Besides, it is understandable that he should assent so eagerly: for to be included, even by name only, among so many names of celebrated scholars is a supreme honor for one who has never before had such an opportunity. “Excuse me,” and my master goes off to the study to fetch his seal. I am tipped to fall unceremoniously onto the matting. Beauchamp helps himself to a slice of sponge cake from the cake-bowl and crams it into his mouth. For a while he seems to be in pain, mumbling. Just for a second I am reminded of my morning experience with the rice-cake. My master reappears with his seal just as the sponge cake settles down in Beauchamp’s bowels. My master does not seem to notice that a piece of sponge cake is missing from the cake-bowl. If he does, I shall be the first to be suspected.

Mr. Beauchamp having taken his departure, my master reenters the study where he finds on his desk a letter from friend Waverhouse.

“I wish you a very happy New Year. . .”

My master considers the letter to have started with an unusual seriousness. Letters from Waverhouse are seldom serious. The other day, for instance, he wrote: “Of late, as I am not in love with any woman, I receive no love letters from anywhere. As I am more or less alive, please set your mind at ease.” Compared with which, this New Year’s letter is exceptionally matter-of-fact:

I would like to come and see you, but I am so very extremely busy every day because, contrary to your negativism, I am planning to greet this New Year, a year unprecedented in all history, with as positive an attitude as is possible. Hoping you will understand. . .

My master quite understands, thinking that Waverhouse, being Waverhouse, must be busy having fun during the New Year season.

Yesterday, finding a minute to spare, I sought to treat Mr. Beauchamp to a dish of moat-bells. Unfortunately, due to a shortage of their ingredients, I could not carry out my intention. It was most regrettable. . .

My master smiles, thinking that the letter is falling more into the usual pattern.

Tomorrow there will be a card party at a certain Baron’s house; the day after tomorrow a New Year’s banquet at the Society of Aesthetes; and the day after that, a welcoming party for Professor Toribe; and on the day thereafter. . .

My master, finding it rather a bore, skips a few lines.

So you see, because of these incessant parties— nō song parties, haiku parties, tanka parties, even parties for New Style Poetry, and so on and so on, I am perpetually occupied for quite some time. And that is why I am obliged to send you this New Year’s letter instead of calling on you in person. I pray you will forgive me. . .

“Of course you do not have to call on me.” My master voices his answer to the letter.

Next time that you are kind enough to visit me, I would like you to stay and dine. Though there is no special delicacy in my poor larder, at least I hope to be able to offer you some moat-bells, and I am indeed looking forward to that pleasure. . .

“He’s still brandishing his moat-bells,” muttered my master, who, thinking the invitation an insult, begins to feel indignant.

However, because the ingredients necessary for the preparation of moat-bells are currently in rather short supply, it may not be possible to arrange it. In which case, I will offer you some peacocks’ tongues. . .

“Aha! So he’s got two strings to his bow,” thinks my master and cannot resist reading the rest of the letter.

As you know, the tongue meat per peacock amounts to less than half the bulk of the small finger. Therefore, in order to satisfy your gluttonous stomach. . .

“What a pack of lies,” remarks my master in a tone of resignation.

I think one needs to catch at least twenty or thirty peacocks. However, though one sees an occasional peacock, maybe two, at the zoo or at the Asakusa Amusement Center, there are none to be found at my poulterer’s, which is occasioning me pain, great pain. . .

“You’re having that pain of your own free will.” My master shows no evidence of gratitude.

The dish of peacocks’ tongues was once extremely fashionable in Rome when the Roman Empire was in the full pride of its prosperity. How I have always secretly coveted after peacocks’ tongues, that acme of gastronomical luxury and elegance, you may well imagine. . .

“I may well imagine, may I? How ridiculous.” My master is extremely cold.

From that time forward until about the sixteenth century, peacock was an indispensable delicacy at all banquets. If my memory serves me, when the Earl of Leicester invited Queen Elizabeth to Kenilworth, peacocks’ tongues were on the menu. And in one of Rembrandt’s banquet scenes, a peacock is clearly to be seen, lying in its pride upon the table. . .

My master grumbles that if Waverhouse can find time to compose a history of the eating of peacocks, he cannot really be so busy.

Anyway, if I go on eating good food as I have been doing recently, I will doubtless end up one of these days with a stomach weak as yours. . .

“‘Like yours’ is quite unnecessary. He has no need to establish me as the prototypical dyspeptic,” grumbles my master.

According to historians, the Romans held two or three banquets every day. But the consumption of so much good food, while sitting at a large table two or three times a day, must produce in any man, however sturdy his stomach, disorders in the digestive functions. Thus nature has, like you. . .

“‘Like you,’ again, what impudence!”

But they, who studied long and hard simultaneously to enjoy both luxury and exuberant health, considered it vital not only to devour disproportionately large quantities of delicacies, but also to maintain the bowels in full working order. They accordingly devised a secret formula. . .

“Really?” My master suddenly becomes enthusiastic.

They invariably took a post-prandial bath. After the bath, utilizing methods whose secret has long been lost, they proceeded to vomit up everything they had swallowed before the bath. Thus were the insides of their stomachs kept scrupulously clean. Having so cleansed their stomachs, they would sit down again at the table and there savor to the uttermost the delicacies of their choice. Then they took a bath again and vomited once more. In this way, though they gorged on their favorite dishes to their hearts’ content, none of their internal organs suffered the least damage. In my humble opinion, this was indeed a case of having one’s cake and eating it.

“They certainly seem to have killed two or more birds with one stone.” My master’s expression is one of envy.

Today, this twentieth century, quite apart from the heavy traffic and the increased number of banquets, when our nation is in the second year of a war against Russia, is indeed eventful. I, consequently, firmly believe that the time has come for us, the people of this victorious country, to bend our minds to study of the truly Roman art of bathing and vomiting. Otherwise, I am afraid that even the precious people of this mighty nation will, in the very near future, become, like you, dyspeptic. . .

“What, again like me? An annoying fellow,” thinks my master.

Now suppose that we, who are familiar with all things Occidental, by study of ancient history and legend contrive to discover the secret formula that has long been lost; then to make use of it now in our Meiji Era would be an act of virtue. It would nip potential misfortune in the bud, and, moreover, it would justify my own everyday life which has been one of constant indulgence in pleasure.

My master thinks all this a trifle odd.

Accordingly, I have now, for some time, been digging into the relevant works of Gibbon, Mommsen, and Goldwin Smith, but I am extremely sorry to report that, so far, I have gained not even the slightest clue to the secret. However, as you know, I am a man who, once set upon a course, will not abandon it until my object is achieved. Therefore my belief is that a rediscovery of the vomiting method is not far off. I will let you know when it happens. Incidentally, I would prefer postponing that feast of moat-bells and peacocks’ tongues, which I’ve mentioned above, until the discovery has actually been made. Which would not only be convenient to me, but also to you who suffer from a weak stomach.

“So, he’s been pulling my leg all along. The style of writing was so sober that I have read it all, and took the whole thing seriously. Waverhouse must indeed be a man of leisure to play such a practical joke on me,” said my master through his laughter.

Several days then passed without any particular event. Thinking it too boring to spend one’s time just watching the narcissus in a white vase gradually wither, and the slow blossoming of a branch of the blue-stemmed plum in another vase, I have gone around twice to look for Tortoiseshell, but both times unsuccessfully. On the first occasion I thought she was just out, but on my second visit I learnt that she was ill.

Hiding myself behind the aspidistra beside a wash-basin, I heard the following conversation which took place between the mistress and her maid on the other side of the sliding paper-door.

“Is Tortoiseshell taking her meal?”

“No, madam, she’s eaten nothing this morning. I’ve let her sleep on the quilt of the foot-warmer, well wrapped up.” It does not sound as if they spoke about a cat. Tortoiseshell is being treated as if she were a human.

As I compare this situation with my own lot, I feel a little envious but at the same time I am not displeased that my beloved cat should be treated with such kindness.

“That’s bad. If she doesn’t eat she will only get weaker.”

“Yes indeed, madam. Even me, if I don’t eat for a whole day, I couldn’t work at all the next day.”

The maid answers as though she recognized the cat as an animal superior to herself. Indeed, in this particular household the cat may well be more important than the maid.

“Have you taken her to see a doctor?”

“Yes, and the doctor was really strange. When I went into his consulting room carrying Tortoiseshell in my arms, he asked me if I’d caught a cold and tried to take my pulse. I said ‘No, Doctor, it is not I who am the patient, this is the patient,’ and I placed Tortoiseshell on my knees. The doctor grinned and said he had no knowledge of the sicknesses of cats, and that if I just left it, perhaps it would get better. Isn’t he too terrible? I was so angry that I told him,‘Then, please don’t bother to examine her, she happens to be our precious cat.’ And I snuggled Tortoiseshell back into the breast of my kimono and came straight home.”

“Truly so.”

“Truly so” is one of those elegant expressions that one would never hear in my house. One has to be the thirteenth Shogun’s widowed wife’s somebody’s something to be able to use such a phrase. I was much impressed by its refinement.

“She seems to be sniffling. . .”

“Yes, I’m sure she’s got a cold and a sore throat; whenever one has a cold, one suffers from an honorable cough.”

As might be expected from the maid of the thirteenth Shogun’s somebody’s something, she’s quick with honorifics.

“Besides, recently, there’s a thing they call consumption. . .”

“Indeed these days one cannot be too careful. What with the increase in all these new diseases like tuberculosis and the black plague.”

“Things that did not exist in the days of the Shogunate are all no good to anyone. So you be careful too!”

“Is that so, madam?”

The maid is much moved.

“I don’t see how she could have caught a cold, she hardly ever went out. . .”

“No, but you see she’s recently acquired a bad friend.”

The maid is as highly elated as if she were telling a State secret.

“A bad friend?”

“Yes, that tatty-looking tom at the teacher’s house in the main street.”

“D’you mean that teacher who makes rude noises every morning?”

“Yes, the one who makes the sounds like a goose being strangled every time he washes his face.”

The sound of a goose being strangled is a clever description. Every morning when my master gargles in the bathroom he has an odd habit of making a strange, unceremonious noise by tapping his throat with his toothbrush. When he is in a bad temper he croaks with a vengeance; when he is in a good temper, he gets so pepped up that he croaks even more vigorously. In short, whether he is in a good or a bad temper, he croaks continually and vigorously. According to his wife, until they moved to this house he never had the habit; but he’s done it every day since the day he first happened to do it. It is rather a trying habit. We cats cannot even imagine why he should persist in such behavior. Well, let that pass. But what a scathing remark that was about “a tatty-looking tom.” I continue to eavesdrop.