Читать книгу Under the Moonlit Sky - Nav K. Gill - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

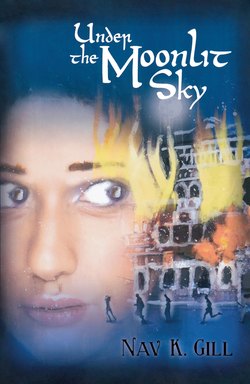

FIVE June 1984

ОглавлениеLadies and gentlemen, please take your seats and fasten your seatbelts. We will begin our descent to the Palam Airport in New Delhi shortly. Thank you.”

My stomach tightened as the airplane descended. So far the flight had been unbearable, and as the plane now began its landing, my impatience grew. Massaging the back of my stiff neck didn’t do much for the discomfort. It must have been over sixteen hours since we’d departed. Thankfully, I had a window seat with no one beside me. The flight wasn’t as packed as I had feared it would be.

“Shit—I hate planes. Why did I have to come all this way?” I complained as I stretched out my arms. The answer, however, was resting on my lap. “Oops. Sorry, Daddy. I didn’t mean to swear again. I can’t wait to get off this plane. You know how I . . .” my voice trailed off.

I realized that I wasn’t speaking to a real person. Instead I was speaking to a box of ashes. It had been a painful experience collecting his urn from the funeral home. My mother’s strong façade had fallen apart as soon as she’d laid eyes upon the urn. Soon after, both my sister and mother had become faint, and so of course, swallowing my emotions, I’d stepped forward and completed the formalities.

Now, however, as I held my father’s urn, I couldn’t help but remember a man who had chased after me during my toddler days; a man who’d picked me up and carried me on his shoulders when I couldn’t walk any further; a man who was very much alive and excited for life and his children. That man was now nothing more than ashes, tied in a bag, secured in a wooden box and placed in a suede emerald sack.

“You did love us, right, Daddy? But, then why did you lie all of these years? And especially when you knew I had found that photo. Why didn’t you say anything then? It would have changed things, changed the way I ended things . . .”

A sea of lights lit up the late-night cityscape below. As the plane glided towards the runway, the crowded streets became more visible. The plane gave a bit of a jolt as it touched down on the tarmac. Just as it came to a stop, I took a deep breath. Here we go.

As soon as I stepped off the plane, I was engulfed in thick smog that carried a rank smell, as if there were month-old dirty socks in every pocket of Delhi. If that wasn’t bad enough, the heat was excruciating. It was like walking into an oven.

Well, this is going to take some getting used to! I thought as I made my way towards the baggage collection area.

While collecting my bags, I noticed that I was being stared at quite a bit. Walking towards the exit, I realized I was still drawing a lot of attention. I usually am quite pleased to attract attention, but the constant stares were admittedly a bit unnerving. I looked down, trying to see if there was something wrong with my clothes or if something was out of place, but there wasn’t, so I just moved on. I desperately hoped my ride was waiting for me.

Once outside, I scanned the curious faces in the crowded gated area through which all arrivals had to pass after collecting their bags. It was mostly men in the crowd. I could barely spot any women. They were shouting out names, smiling and waving at their relatives. Eventually my gaze landed on a short, skinny, dark-complexioned man with large round eyes. He was holding a sign that read: Esha Kaur Sidhu—Canada.

“Kaur? Great, I’m not even out of the airport yet, and they’re already turning me into a full-fledged Sikh . . . Indian . . . whatever!” I walked up to the man with the sign, and he looked relieved that he had finally found me. I smiled and offered my hand. “Hi, I’m Esha. Just simple Esha, not EEE-sha, but like the sound of an ‘a’, okay, Esha. And please no Kaur, okay?”

He eyed my offered hand nervously, simply nodded and said, “Hello, ma’am. I am Chotu, the family driver.”

“Chotu? Is that your full name?” I asked in Punjabi as I took my hand back. As expected, he didn’t speak English.

“No, ma’am. It is Chandrasheiker Singh. Everybody calls me Chotu, well, because as you can see, I am not so very tall. It is since childhood. Just Chotu,” he said smiling, clearly pleased that I had taken interest in his name. I followed him to a medium-sized white car in the airport parking lot. The stares from passersby still had not ceased.

“So, Chotu, why is it that wherever I pass, people are staring at me?”

Chotu found this funny. “Oh, ma’am, do not worry too much about it. You are a very fair-looking young woman. It is only normal that they will stare at a foreigner such as yourself.”

“I see. So, uh . . . where’s the family? I mean, I thought Ekant would come to collect me.”

“Sir was busy with business, so he sent me to receive you. The family is eagerly awaiting your arrival at home. It is the first time we are having a foreign guest visit. Everyone is very excited to see you, but also very sad to hear about your father.” Chotu lowered his gaze to the urn held tightly in my hands.

“Yeah, me too,” I sighed as I climbed into the backseat and he loaded up my baggage.

The drive to the house didn’t take very long. After the time it had taken to get through customs, collect my bags and exit the airport, it had gotten pretty late, almost midnight. Therefore, as Chotu explained, the streets now were clear for a smooth, traffic-free drive.

I rolled down my window, hoping to feel a breeze. The humidity was making my hair frizz, so I tied it back. The last thing I should do is show up looking like a crazy bag lady. I straightened my clothes and tried to make myself look presentable. I did the best I could from the backseat of the car and in such poor light. A spritz of perfume and the cool feel of lotion on my arms and face was incredibly refreshing, especially in this smoggy atmosphere.

Besides the smog, New Delhi didn’t appear to be so bad. It was quite dark, but the roads were paved, and there were traffic lights, even though I realized my driver wasn’t exactly paying any attention to them, or to the speed limit, if there was any. As yet, I hadn’t seen a sign with a limit on it.

“That, ma’am, is India Gate. Many foreigners come here to take pictures of it.” Chotu pointed towards a massive arch-like monument that had been erected in a spacious road crossing. It really did look like a gate, but it was enormous. It was lit up in the dead of night. Such a simple structure, yet so beautiful.

“What’s this gate for, Chotu?” I asked, curious to know why anyone would want to build a gate as a monument.

“It is actually a war memorial for the Indians who gave their life in the First World War and in the Afghan wars. It is a good thing to remember those who have died to protect others.”

“It’s beautiful,” I replied as it fell behind us in the distance.

A few more minutes passed, then we pulled into a different neighbourhood. Each house had a gate in front, and each was different from the next in both size and shape, but it was difficult to see them properly in the dark. The bright city lights had disappeared, and right now the only source of light was from the moon. Chotu stopped in front of a double gate and honked the horn until there was movement behind it, and eventually it swung open. Once in the courtyard, he cut the engine. Slowly climbing out of the car, I examined my surroundings. It was an open courtyard with a balcony running all the way around the second floor of the house. The ground was cement, as were the walls. There was a combination of screen doors and wooden doors on every side, leading to what I assumed were bedrooms and sitting areas. Right by the front gate, however, a strange dark shadow caught my eye. As I looked closer I realized it was . . . a . . . a cow. Why was there a cow in the courtyard of the house?

“Chotu! Chotu, you have returned safely?” A slightly overweight old woman of medium height was slowly making her way through one of the doors to the right. She was wrapped in a white shawl that she had also draped over her head. She had half-moon spectacles on, but her extremely fair complexion was visible underneath, even in the dark. I carefully examined her before recognizing her from the photo my mom had shown me. She was my grandmother; my Dhadhi. She moved slowly, with a slight limp, but she kept her gaze steady as she smiled and made her way towards me.

“Ah, my child! My Dilawar’s daughter! Let me look at you!” She rested her hand on my cheek and analyzed me from top to bottom, after which she settled her gaze once again upon my face. Her smile grew wider and wider with each passing moment, but after the long look, tears slowly began to roll down her face. “You remind me just of your father. He was very handsome when he was your age. You have his face.” She threw her arms around me and wept softly.

I didn’t quite know what to say in return. My father’s urn was still in my hand. I tried to balance it with my left hand while I wrapped my right arm around her.

“Dhadhi, I’m very happy to finally meet you. Dad always talked a lot about you. The family misses you very much.” I repeated what my mother had told me to say and hoped that it would offer her some comfort.

I had never known the love of a grandmother. My mom’s parents had both passed away when I was just a baby. I used to ask my father why his parents didn’t live in Canada with the rest of us, and of course he had always just shrugged it off.

“Oh, is this him? Is this my child?” Dhadhi asked, looking at the emerald sack held in my hand.

“Yes, it’s Daddy’s . . . well, yes,” I stammered, holding it up for her to see properly.

“May I?” she asked softly, her eyes firmly fixed on the object before her.

“Of course, I mean, you are his mother,” I answered carefully as I moved it in her direction. I feared triggering any further emotion in her. I wasn’t new to seeing Indian women grieve. The days and weeks immediately following my father’s passing were still fresh in my memory. The women were uncontrollable in many respects.

She hesitated for a moment as tears continued to stream down her fair but aged face. She held up her hands and caressed it before taking it into her grasp. She then removed the green sack, kissed the top of the wooden box and held it tightly against her bosom. I stood watching her as she wept harder and cried out for her son, whom she had not seen for almost thirty years. I felt a cold chill go down my neck as I watched the immensely emotional and tragic interaction of a mother searching for the warmth of her son in a wooden box of ashes. As disconcerting as the image was for me, I couldn’t help but feel sad for her. My face began to feel hot, and my vision blurred, enough for me to realize that I too had tears streaming down my face.

As I watched her cry, I felt a fire burn within me. My stomach felt like it was doing flip-flops, and my breathing became heavier. I couldn’t bear seeing her in this state of despair. I wanted to hug her and tell her that everything was going to be all right. I wanted to reassure her that she was loved. All the feelings that I had for my mother were now being directed towards this old woman whom I had never known or met until this moonlit night.

Was this the love between a grandparent and a grandchild? What I had missed my entire life until now? Perhaps it was mere pity or a reflection of my own sadness at losing my father?

As I stood debating my feelings, another woman came through another one of the doors and made directly for Dhadhi, where she wrapped her arms around her and told her what I could not. “Dhadhi, calm yourself. Have faith in Waheguru. Everything will be made all right by Him.”

“Yes, child, you are right,” Dhadhi replied as she wiped her tears and placed the urn back into the rich emerald sack.

“You must be Esha,” the woman said as she looked my way with a smile, then pulled me into a gentle embrace. She stood as tall as me and wore a traditional salwar-kameez, with a shawl draped around her. Her thick black hair was tied back into a neat bun. She too had a fair complexion that was visible under the moonlight. There was a glow in her large round eyes that hinted at a warm and kind-hearted character.

“Yeah, I’m Esha. I just got here.”

“I am Jas! Well, Jasdeep, but no one calls me by my full name. I am Ekant’s wife! So that makes me your sister-in-law!” she said with a wide smile, showing that she was genuinely excited at the prospect of our relationship.

“Wow, wife, eh? I didn’t know Ekant was married,” I blurted out, not knowing how foolish I might seem in front of her, not knowing such an important thing about my own family.

“Really? Well then, there is a lot you do not know, but it is a good thing you came. We can now become better acquainted,” she replied, still smiling. “However, I am very sorry to hear about your father. Even though he was Ekant’s uncle, Ekant has always viewed him as his own father.” Her gaze fell to the urn. There was an awkward silence as she continued to look at it, as though she were lost in deep thought. The sudden silence made me uncomfortable.

“So, um . . . where is Ekant?” I asked in an effort to change the subject. I was curious to meet him and to find out why he hadn’t come to collect me from the airport himself. I felt he could have at least made the effort.

“Oh,” Jas said, “he was called away by one of his business associates. Some business matter.”

“This late at night?” I asked.

“Well, time is not really an issue,” she replied. “I am sure it was important, otherwise he would not have left, especially when you were due to arrive. Now, come on in. We’ve spent way too long standing out here. You must be tired. Allow us to get you settled in.” She began to shuffle about, checking the car to make sure I hadn’t left anything, then she led me to a nearby door.

Watching her closely, I could sense that she was making a concerted effort to make it appear as if there was nothing fishy about Ekant’s absence. Perhaps it was just business, but at midnight? I had flown thousands of miles with my father’s ashes. It was the first time I was to meet this mysterious son of the family, and he wasn’t here. A little voice in my head kept telling me that things might not be so smooth after all, and that made me nervous.

I followed Jas and Dhadhi into what appeared to be a living room. The light was quite dim. The room was simple, yet colourful and spacious. Yellow glass adorned the windows directly opposite to where I was standing in the doorway. Sofas with green fabric and wooden frames were set up in the middle of the room, along with black chairs and a red rug beneath them. There was a wooden desk, and bookshelves were scattered along the walls. The opening behind the living room revealed a dining area, and there were doors leading outside and doors on the left and right, which I figured were for other rooms in the house. The family wasn’t much for decorating, though. None of the furniture matched, really. There were just simple wooden things thrown together to fill the space.

“Esha, this is the sitting room, and the kitchen is through the door on the right, just behind the dining table,” Jas said as she pointed to yet another brown wooden door on the right. “I’ll show you your room, where you can freshen up, unpack, then you can eat. You must be hungry.”

“I actually had dinner right before the plane landed, so I’m okay. I’m just very tired, but thanks.”

“Esha, child, you must eat something. You have travelled so far,” insisted Dhadhi.

“No, Dhadhi, it’s okay. I’m fine. I just need to sleep; it’s been a long trip. Where is everyone else though, I mean, Ekant’s mother, is . . .”

“She is no longer with us,” Jas said quickly, cutting me off. “Um . . . sadly she passed away three years ago.”

Ouch, way to go, Esha!

“Oh . . . I’m . . . I’m really sorry. I wasn’t told,” I mumbled in embarrassment.

“That’s okay. Well, follow me,” Jas replied as she led the way through the hallway on the left.

I followed her up a small set of cement stairs to the second floor and into a large, dark bedroom, as Dhadhi trailed behind us. There was a stale smell in the room, indicating that it wasn’t used very often.

“Sorry, the electricity in the area has been acting funny all day,” Jas explained as she lit a lamp on the dressing table. “This should help out for tonight. I placed new clean sheets on the bed. The nights can be chilly, so I put a blanket out as well for you just in case. As you can see, Chotu has already brought up your suitcases. This room has a washroom connected to it, and it is all yours, so please feel at home. Dhadhi Ji’s room is right next to yours on the left, if you need anything, and Ekant and I are just down the hall. Are you sure you do not want anything to eat?”

“Yeah, don’t worry. I’m fine,” I said impatiently. All I wanted was a shower and to get out of my sweaty clothes.

“Here, child,” came Dhadhi’s voice as she held up the emerald sack. She had been so quiet that I had almost forgotten she was still in the room with us, holding the urn. “This belongs to you, keep it safe.”

I gently retrieved the urn from her trembling hands and placed it on the dressing table before turning to my newfound family members and bidding them good night.

“We will see you in the morning, Esha!” Jas called out as she guided the weeping Dhadhi out of the room. “Dhadhi Ji, you must control your emotions,” I could hear her say as they made their way down the hallway stairs.

Alone at last!

“Ugh! I’m so tired and hot!” I complained as I threw off my pullover. “I can’t believe Mom made me wear this thing in this heat.”

“Don’t go showing off those arms and bare skin when you arrive in Delhi,” she had said as we raced towards my gate in the airport. “Make sure you cover up! It is not Canada over there!”

“I’d like to see her wearing a sweatshirt in this heart,” I said as I turned my attention to the room I was going to be sleeping in for the next week.

The bed was quite large, possibly a king size. There was only one mattress on it, which was draped in a red sheet. Jas had placed a thin white blanket on top. Similar to the living room, the furniture was wooden. The left side of the room consisted of a wooden dresser and cabinet, and to the right was a painted blue door leading to the washroom. There was a framed painting on either side of the washroom door. The left one had two young boys standing in front of an incomplete wall. They were clad in orange garb and stood side by side with one arm raised. I figured it had to be some kind of revolutionary Indian thing.

The painting on the right, however, was that of a male and was much more familiar. My mother had a similar painting back home. It was of some Sikh Guru, whose name I couldn’t really remember at the moment. This particular one was clad in a yellow and blue robe with a gold turban. A red feather ran along the top of the turban, while a smaller peacock feather stuck out in front. His right hand held up a sword with a golden handle, while the left arm held onto the reins of a white horse. These too were painted in gold. It wasn’t your typical saintly photo. This Sikh Guru, with the extravagant attire and largely defined eyes, looked like a determined prince riding out to battle.

My attention was suddenly diverted by movement in my belly. I hadn’t gone to the washroom since my connection in London. I quickly stepped into the washroom and hit the light.

“What the . . . where is the . . .” Words escaped me as I turned my head in every direction, seeking a toilet. I scratched my head in confusion. There was no toilet! There was a shower head on the left and a small white sink on the wall in the middle, but no toilet.

“Great! Where am I supposed to go now?” I cried out as I held onto my stomach, which was now becoming more and more impatient. Just as I turned to leave, I noticed a glimmer in the right corner. It was a chain. My eyes trailed the length of the chain, and I realized it was attached to a small, thin pipe that ran along the ceiling and down the back wall. As I looked down, I noticed a hole. There were tiles in place, outlining the oval shape; a shape that looked very much like . . . like the seat of a toilet.

“Ugh! This can’t be it. This cannot be the toilet!” I said, looking around the washroom again, hoping that a regular, civilized toilet would just magically materialize and save me. No such luck.

“Okay, Esha pull yourself together,” I said as I tried to calm myself, “and face the fact that you have to go, even if it’s . . . it’s . . . on . . . or . . . in . . . this thing. But first, I have to be sure.”

I grabbed a hold of the chain, took a deep breath and gave it a yank. There was a gurgling sound, followed by the sound of water. I looked down at the hole and saw that a small wave of water had splashed into it, and hopefully retreated as well.

“I guess I have no choice,” I concluded as the moans from my stomach grew louder by the minute. I had to go badly. With a sigh, I closed the washroom door behind me and locked it. The last thing I wanted was to be caught with my pants down squatting over a hole on my first night in India. First I bent down and took a long careful look at the hole, just to make sure that nothing was lurking inside it. I shuddered at the thought of a snake slithering up. I shook my head and tried to breathe. Finally, confident that the coast was clear, I stood up and planted my feet on either side of the hole. I pulled down my pants and squatted.

“Oh, no!” I cried out, standing up before anything started. “Toilet paper!” I looked around once again and found nothing. So I ran back into the bedroom and threw open my suitcase. There lay a half-dozen rolls of toilet paper. Thinking back, I felt stupid that I had made fun of my mother when she was loading these rolls into my suitcase. She had insisted that I would have use for them, and I’d thought she was just wasting precious luggage space. Why wouldn’t they have toilet paper?

“Thanks, Mom!” I said as I ran back into the washroom. I locked the door once again and took my position above the hole. I have to admit, it wasn’t as uncomfortable as it had appeared it would be, but it took a lot of concentration and aim. After a few minutes, I stood up and retreated. I yanked the chain, eagerly waiting for the water to splash away the remains, but nothing happened. I yanked the chain even harder, but again nothing happened.

“This is just freakin’ great! Now what?” I was beginning to panic. “Please, please, please, oh wonderful Mr. Chain, just flush!” I begged. I held onto the chain once again and pulled it down hard, only this time I held it down for a while longer. After what seemed like an eternity, the gurgling sound appeared, and water began to splash into the hole. “Yes! Thank you, thank you, thank you!” I cried as I made my way to the sink to wash my hands then ran out of the washroom, closing the door behind me.

I looked at my watch; a half hour had passed. With slightly sore legs and a nauseous feeling, but with relief that it was behind me, I fell onto the bed and closed my eyes. I was exhausted.