Читать книгу The Perfect Mile - Neal Bascomb - Страница 9

Оглавление1

I have now learned better than to have my races dictated by the public and the press, so I did not throw away a certain championship merely to amuse the crowd and be spectacular.

Jack Lovelock, 1,500m gold medallist, 1936 Olympics

On 16 July 1952 at Motspur Park, south London, two men were running around a black cinder track in singlets and shorts. The stands were empty, and only a scattering of people watched former Cambridge miler Ronnie Williams as he tried to stay even with Roger Bannister, who was tearing down the straight. It was inadequate to describe Bannister as simply ‘running’: eating up yards at a rate of seven per second, he was moving too fast to call it running. His pacesetter for the first half of the time trial, Chris Chataway, had been exhausted, and the only reason Williams hadn’t folded was that all he needed to do was maintain the pace for a lap and a half. What most distinguished Bannister was his stride. Daily Mail journalist Terry O’Connor tried to describe it: ‘Bannister had terrific grace, a terrific long stride, he seemed to ooze power. It was as if the Greeks had come back and brought to show you what the true Olympic runner was like.’

Bannister was tall – six foot one – and slender of limb. He had a chest like an engine block and long arms that moved like pistons. He flowed over the track, the very picture of economy of motion. Some said he could have walked a tightrope as easily, so balanced and even was his foot placement. There was no jarring shift of gears when he accelerated, as he did in the last stage of the three-quarter-mile time trial, only a quiet, even increase in tempo. Bannister loved that moment of acceleration at the end of a race, when he drew upon the strength of leg, lung, and will to surge ahead. Yes, Bannister ran, but it was so much more than that.

As he sped to the finish with Williams at his heels, Bannister’s friend Norris McWhirter prepared to take the time on the sidelines. He held his thumb firmly on the stopwatch button, knowing that because of the thumb’s fleshiness, having it poised only lightly added a tenth of a second at least. Bannister shot across the finish; McWhirter punched the button. When he read the time, he gasped.

Norris and his twin brother Ross had been close to Bannister since their days at Oxford University. They were three years older than the miler, having served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War, but they had been Blues together in the university’s athletic club. Norris had always known there was something special about Roger. Once, during an Italian tour with the Achilles Club (the combined Oxford and Cambridge athletic club), which Bannister had dominated, McWhirter had looked over with amazement at his friend sleeping on the floor of a train heading to Florence and thought, ‘There lies the body that perhaps one day will prove itself to possess a known physical ability beyond that of any of the one billion other men on earth.’ Sure enough, as McWhirter stared down at his stopwatch that July afternoon, he could hardly believe the time: Bannister had run three-quarters of a mile in 2:52.9, four seconds faster than the world record held by the great Swedish miler Arne Andersson.

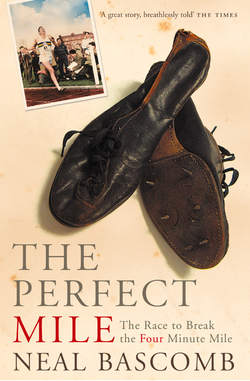

After gathering his breath, Bannister walked over to see what the stopwatch read. Cinders clung to his running spikes. At the time, athletics shoes were simply a couple of pieces of thin leather that moulded themselves so tightly to the feet when the laces were drawn that one could see the ridges of the toes. The soles were embedded with six or more half-inch-long steel spikes for traction. Running surfaces, too, had advanced very little over the years. They were mostly oval dirt strips layered on top with ash cinders that were taken from boilers at coal-fired electricity plants. Track quality depended on how well the cinders were maintained, since in the sun they became loose and tended to blow away, and when it rained the track turned to muck. Motspur Park’s track benefited from the country’s best groundskeeper, and it was one of the fastest, which was why Bannister had chosen it for this time trial.

He always ran a three-quarter-mile trial before a race to fix in his mind his fitness level and pace judgement. This trial was particularly important because in ten days’ time, given that he qualified in the heats, he would run the race he had dedicated the past two years to winning: the Olympic 1,500m final. A good time this afternoon was crucial for his confidence.

‘Two fifty-two nine,’ McWhirter said.

Bannister was taken aback. Williams and Chataway were just as incredulous. The time had to be wrong.

‘At least, Norris, you could have brought a watch we could rely on,’ Bannister said.

McWhirter was cross at such a suggestion. But he knew one way to make sure his stopwatch was accurate. He dashed to the telephone booth near the concrete stadium stands, put in a penny coin, and dialled the letters T-I-M. The phone rang dully before a disembodied voice came on to the line, tonelessly saying, ‘And on the third stroke, the time will be two thirty-two and ten seconds – bip–bip–bip – and on the third stroke, the time will be two thirty-two and twenty seconds – bip–bip–bip …’ Norris checked his stopwatch: it was accurate.

After McWhirter returned and confirmed the result to the others, they agreed that Bannister was certain of a very good show in Helsinki. They dared not predict a gold medal, but they knew that Bannister considered a three-minute three-quarter mile the measure of top racing shape. He was now seven seconds under this benchmark. All of his training for the last two years had been focused on reaching his peak at exactly this moment – and what a peak it was. He was in a class by himself. The critics – coaches and newspaper columnists – who had condemned him for following his own training schedule and not running in enough pre-Olympic races would soon be silenced.

There was, however, a complication, which McWhirter had yet to tell Bannister. As a journalist for the Star, McWhirter kept his ear to the ground for any breaking news, and he had recently heard something very troubling from British Olympic official Harold Abrahams. Because of the increased number of entrants, a semi-final had been added to the 1,500m contest. In Helsinki, Bannister would have to run not only a first-round heat, but also a semi-final before reaching the final.

The four men bundled into McWhirter’s black Humber and headed back to the city for the afternoon.

When Bannister was not racing around the track, where he looked invincible, the 23-year-old appeared slighter. In trousers and a shirt, his long corded muscles were no longer visible, and it was his face one noticed. His long cheekbones, fair complexion, and haphazard flop of straw-coloured hair across the forehead gave him an earnest expression that turned boyish when he smiled. However, there was quiet aggression in his eyes. They looked at you as if he was sizing you up.

As Norris McWhirter turned out of the park, he finally said, ‘Roger … they put in a semi-final.’

They all knew what he meant: three races in three days. Bannister had trained for two races, not three. Three required a significantly higher level of stamina; Bannister had concentrated on speed work. With two prior races, the nervous energy he relied on would be exhausted by the final – if he made the final. It was as if he were a marksman who had precisely calibrated the distance to his target, then found that his target had been moved out of range. Now it was too late to readjust the sights.

Bannister looked out the window, saying nothing. Away from Motspur Park with its trees and long stretches of open green fields, the roads were choked with exhaust fumes and bordered by drab houses and abandoned lots overgrown with weeds. The closer they got to London, the more they could see of the war’s destruction, the craters and bombed-out walls that had yet to be bulldozed and rebuilt. A fine layer of soot clouded the windows and greyed the rooftops.

The young miler didn’t complain to his friends, although they knew he was burdened by the fact that he was Britain’s great hope for the 1952 Olympics. He was to be the hero of a country in desperate need of a hero.

To pin the hopes of a nation on the singlet of one athlete seemed to invite disaster, but Britain at that time was desperate to win at something. So much had gone wrong for so long that many questioned their country’s standing in the world. Their very way of life had come to seem precarious. ‘It is gone,’ wrote James Morris of his country in the 1950s. ‘Empire, forelock, channel and all … the world has overtaken [us]. We are getting out of date, like incipient dodos. We have reached, none too soon, one of those immense shifts in the rhythm of a nation’s history which occur when the momentum of old success is running out at last.’ The First World War had put an end to Britain’s economic and military might. The depression of the 1930s slowly drained the country’s reserves, and its grasp on India started to slip. Britain moved reluctantly into the Second World War, knowing it couldn’t stand alone against Hitler’s armies. Once the British joined the fight, they had to throw everything into the effort to keep the Nazis from overrunning them. When the war was over they discovered, like the Blitz survivors who emerged onto the street after the sirens had died away, that they were alive, but that they had grim days ahead of them.

Grim days they were. Britain owed £3 billion, principally to the United States, and the sum was growing. Exports had dried up, in large part because half of the country’s merchant fleet had been sunk. Returning soldiers found rubble where their homes had once stood. Finding work was hard, finding a place to live harder. Shop windows remained boarded up. Smog from coal fires deadened the air. Trash littered the alleys. There were queues for even the most basic staples, and when one got to the front of the line, a ration card was required for bread (three and a half pounds per person per week), eggs (one per week), and everything else (which wasn’t much). Children needed ration books to buy their sweets. Trains were overcrowded, hours off schedule, and good luck finding a taxi. If this was victory, asked a journalist, why was it ‘we still bathed in water that wouldn’t come over your knees unless you flattened them?’

And the blows kept falling. The winter of 1946–7, the century’s worst, brought the country to a standstill. Blizzards and power outages ushered in what the Chancellor of the Exchequer called the ‘Annus Horrendus’. It was so cold that the hands of Big Ben iced up, as if time itself had stopped. Spring brought severe flooding, and summer witnessed extremely high temperatures. To add to the misery, there was a polio scare.

Throughout the next five years, ‘austerity’ remained the reality, despite numerous attempts to put the country back in order. Key industries were nationalised, and thousands of dreary prefabricated houses were built for the homeless. In 1951 the Festival of Britain was staged to brighten what critic Cyril Connolly deemed ‘the largest, saddest and dirtiest of the great cities, with its miles of unpainted half-inhabited houses, its chopless chop-houses, its beerless beer pubs … its crowds mooning around the stained green wicker of the cafeterias in their shabby raincoats, under a sky permanently dull and lowering like a metal dish-cover’. The festival, though a nice party, was an obvious attempt to gloss over people’s exhaustion after years of hardship. Those who were particularly bitter said that the festival’s soaring Skylon was ‘just like Britain’, standing there without support. To cap it all, on 6 February 1952 London newspapers rolled off the presses with black-bordered pages: the king was dead. Crowds wearing black armbands waited in lines miles long to see George VI lying in state in Westminster Abbey. As they entered the hall, only the sounds of footsteps and weeping were heard. A great age had passed.

The ideals of that bygone age – esprit de corps, self-control, dignity, tireless effort, fair play, and discipline – were often credited to the country’s long sporting tradition. It was said that throughout the empire’s history, ‘England has owed her sovereignty to her sports.’ Yet even in sport she had recently faltered. The 1948 Olympic Games in London had begun badly when the Olympic flame was accidentally snuffed out on reaching England from Greece. America (the ‘United, Euphoric, You-name-it-they-had-it States’ as writer Peter Lewis put it) dominated the games, winning thirty-eight gold medals to Britain’s three. After that the country had to learn the sour lesson of being a ‘good loser’ in everything from football and cricket to rugby, boxing, tennis, golf, athletics, even swimming the Channel. It looked as though the quintessential English amateur – one who played his sport solely for the enjoyment of the effort and never at the cost of a complete life – simply couldn’t handle the competition. He now looked outdated, inadequate, and tired. For a country that considered its sporting prowess symbolic of its place in the world, this was a distressing situation.

Roger Bannister, born into the last generation of the age that ended with George VI’s death, typified the gentleman amateur. He didn’t come from a family with a long athletic tradition, nor one in which it was assumed he would go to Oxford, as he did, to study medicine and spend late afternoons at Vincent’s, the club whose hundred members represented the university’s elite.

His father, Ralph, was the youngest of eleven children raised in Lancashire, the heart of the English cotton industry and an area often hit by depression. Ralph left home at 15, took the British Civil Service exams, qualified as a low-level clerk, and moved to London. Over a decade later, after working earnestly within the government bureaucracy, he felt settled enough to marry. He met his wife Alice on a visit back to Lancashire, and on 23 March 1929 she gave birth to their first son and second child, Roger Gilbert. The family lived in a modest home in Harrow, north-west London. Forced to abandon their education before reaching university (his mother had worked in a cotton mill), Roger’s parents valued books and learning above everything else. All Roger knew of his father’s athletic interests was that he had once won his school mile and then fainted. Only later in life did he learn that his father carried the gold medal from that race on his watch chain.

Bannister discovered the joy of running on his own while playing on the beach. ‘I was startled and frightened,’ he later wrote of his sudden movement forward on the sand in bare feet. ‘I glanced round uneasily to see if anyone was watching. A few more steps – self-consciously … the earth seemed almost to move with me. I was running now, and a fresh rhythm entered my body.’ Apart from an early passion for moving quickly, nothing out of the ordinary marked his early childhood. He spent the years largely alone, building models, imagining heroic adventures, and dodging neighbourhood bullies, like many boys his age.

When he was 10 this world was broken; an air-raid siren sent him scrambling back to his house with a model boat secured under his arm. The Luftwaffe didn’t come that time, but soon they would. His family evacuated to Bath, but no place was safe. One night, when the sirens sounded and the family took refuge underneath the basement stairs of their new house, a thundering explosion shook the walls. The roof caved in around them, and the Bannister family had to escape to the woods for shelter.

Although the war continued to intrude on their daily lives, mostly in the form of ration books and blacked-out windows, Roger had other problems. As an awkward, serious-minded 12-year-old who was prone to nervous headaches, he had trouble fitting in among the many strangers at his new school in Bath. He won acceptance by winning the annual cross-country race. The year before, after he had finished eighteenth, his house captain had advised him to train, which Bannister had done by running the two-and-a-half-mile course at top speed a couple of times a week. The night before the race the following year he was restless, thinking about how he would chase the ‘third form giant’ who was the favourite. The next day Bannister eyed his rival, noting his cockiness and general state of unfitness. When the race started, he ran head down and came in first. His friends’ surprise would have been trophy enough, but somehow this race seemed to right the imbalance in his life as well. Soon he was able to pursue his studies, as well as interests in acting, music, and archaeology, without feeling at risk of being an outcast – as long as he kept winning races. Possessed of a passion for running, a surfeit of energy, and a preternatural ability to push himself, he won virtually all of them, usually wheezing for breath by the end.

Before he left Bath to attend the University College School in London, the headmaster warned, ‘You’ll be dead before you’re 21 if you go on at this rate.’ His new school had little regard for running, and Bannister struggled to find his place once again. He was miserable. He tried rugby but wasn’t stocky or quick enough; he tried rowing but was placed on the third eight. After a year he wanted out, so at 16 he sat for the Cambridge University entrance exam. At 17 he chose to take a scholarship to Exeter College, Oxford, since Cambridge had put him off for a year. He never had a problem knowing what he wanted.

Bannister intended to study to become a doctor, but he knew he needed a way not only to fit in but to excel among his fellow students, most of whom, in 1946, were eight years older than he, having deferred placement because of the war. A schoolboy among ex-majors and brigadiers, he realised that running was his best chance to distinguish himself. The year before, his father had taken him to see the gutsy, diminutive English miler Sydney Wooderson take on the six-foot giant Arne Andersson at the first international athletics competition since the war’s end. White City stadium, located in west London, was bedlam as Andersson narrowly beat Wooderson. ‘If there was a moment when things began, that was it for me,’ Bannister later said. In a foot race, unlike other sports, greatness could be won with sheer heart. He sensed he had plenty of that.

Before he even unpacked his bags at Oxford, Bannister sought out athletes at the track. He found no one there, but discovered a notice on a college bulletin board for the University Athletic Club. He promptly mailed a guinea to join but received no response. He decided to go running on the track anyway, even though one of the groundskeepers advised, ‘I’m afraid that you’ll never be any good. You just haven’t got the strength or the build for it.’ Apparently the groundskeeper thought everyone needed to look like Jack Lovelock, the famous Oxford miler: short, compact, with thick, powerful legs. The long-limbed, almost ungainly Bannister persisted nonetheless. Three weeks later, having finally received his membership card, he entered the Freshman’s Sport mile wearing an oil-spotted jersey from his rowing days. He thought it best to lead from the start – a strategy he would afterwards discard – and finished the race in second place with a time of 4:52. After the race, the secretary of the British Olympic Association advised him, ‘Stop bouncing, and you’ll knock twenty seconds off.’ Bannister had never before worn running spikes, and their grip on the track had made him, as he later described, ‘over-stride in a series of kangaroo-like bounds’.

The cruel winter of 1946–7, with its ten-foot snowdrifts, meant that someone had to shovel out a path on the track so the athletes could train; Bannister took to the yeoman’s task, and for his effort won a third-string spot in the Oxford versus Cambridge mile race on 22 March 1947. On that dreary spring day, on the very track at White City where he had watched Wooderson compete, Bannister discovered his true gift for running. He stepped up to the mark feeling the pressure to run well against his university’s arch rival. From the start Bannister held back, letting the others set the pace. The track was wet, and the front of his singlet was spotted black with cinder ash kicked up by the runners ahead of him. After the bell for the final lap, Bannister was exhausted but still close enough to the leaders to finish respectably. All of a sudden, though, he was overwhelmed by a feeling that he just had to win. It was instinct, a ‘crazy desire to overtake the whole field’, as he later explained. Through a cold, high wind on the back straight, he increased the tempo of his stride, and to everyone’s shock, team-mates and competitors alike, he surged past on the outside. In the effort inspired by the confluence of body and will, he felt more alive than ever before. He pushed through the tape twenty yards ahead of the others in 4:30.8. It wasn’t the time that mattered, rather the rush of passing the field with his long, devouring stride. This was ecstasy, and it was the first time Bannister knew for sure there was something remarkable in the way he ran – and something remarkable in the feeling that went with it.

After the race he met Jack Lovelock, the gold medallist in the 1,500m at the 1936 Olympics and the former world record holder in the mile. ‘You mean the Jack Lovelock,’ Bannister said on being introduced. Lovelock was a national hero, Exeter graduate, doctor, and blessed with tremendous speed. It didn’t take much insight on his part to see in Bannister the potential resurrection of British athletics.

Bannister didn’t disappoint. On 5 June he clocked a 4:24.6 mile, beating the time set by his hero Wooderson when he was the same age, 18. In the summer Bannister travelled with the English team on its first post-war international tour, putting in several good runs. In November he was selected as a ‘possible’ for the 1948 Olympics, then turned down the invitation. He wasn’t ready, he decided, to some criticism.

It was in his nature to listen to his own counsel, not that of others. He had taken a coach, Bill Thomas, who had once trained Lovelock, but Bannister soon became disgruntled with him. Thomas attended to Bannister on the track while wearing a bowler hat, suit and waistcoat. He barked instructions at the miler on how to hold his arms or how many laps to run during training. When the young miler asked for the reasoning behind the lessons, Thomas simply replied, ‘Well, you do this because I’m the coach and I tell you.’ When Bannister ran a trial and enquired about his time, Thomas said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about that.’ Soon Bannister dropped him, preferring to discover for himself how to improve his performances.

The next year he became Oxford Athletic Club secretary, then quickly its president. He won the Oxford versus Cambridge meet for the second year; he competed in the Amateur Athletic Association (AAA) championships in the summer, learning the ropes of first-class competition. Increasingly the newspapers headlined his name. He even saved the day at the opening ceremony for the Olympics when it was discovered that the British team hadn’t been given a flag with which to march into the stadium. Bannister found the back-up flag, smashing the window of the commandant’s car with a brick to retrieve it.

Four years later, he intended to save the British team’s honour again.

Roger Bannister’s preparations for the Helsinki Games began in the autumn of 1950. He had spent the two previous years studying medicine, soaking up university life, hitch-hiking from Paris to Italy, and going on running tours to America, Greece, and Finland. His body filled out. He won some races and lost others but, importantly, he turned himself from an inexperienced, weedy kid into a young man who clearly understood that Oxford and running had opened up worlds to him that otherwise would have remained closed. He was ready to make his Olympic bid, and afterwards to put away his racing spikes for a life devoted to medicine.

Bannister’s plan was to spend one year competing against the best international middle-distance runners in the world, learning their strengths and weaknesses and acclimatising to different environments. Then, in the year before the Games, he would focus exclusively on training to his peak, running in only a few races so as not to take off his edge. The plan was entirely his own. Having spoken to Lovelock about his preparations for the 1936 Olympics, Bannister felt he needed no other guidance.

First he flew to New Zealand over Christmas for the Centennial Games, where he beat the European 1,500m champion Willi Slijkhuis and the Australian mile champion Don Macmillan, both of whom he was likely to face in Helsinki. His mile time was down to 4:09.9, a reduction of more than forty seconds from his first Oxford race three years earlier. While in New Zealand he visited the small village school Lovelock had attended, noticing that the sapling given to the Olympic gold medal winner had now grown into an oak tree. The symbolism wasn’t lost on him. Back in England Bannister continued his fellowship in medicine through the spring of 1951 at Oxford, where he investigated the limits of human endurance and chatted with such distinguished lecturers as J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. He then flew to Philadelphia to compete in the Benjamin Franklin Mile, the premier American event in middle-distance running. The press fawned over this foil to the American athlete, commenting on his travelling alone to the event: ‘No manager, no trainer, no masseur, no friends! He’s nuts – or he’s good.’ In front of forty thousand American fans, Bannister crushed the country’s two best milers in a time of 4:08.3. The New York Herald Tribune described him as the ‘worthy successor to Jack Lovelock’. The New York Times quoted one track official as saying, ‘He’s young, strong and fast. There’s no telling what he can do.’

The race brought Bannister acclaim back home. To beat the Americans on their own turf earned one the status of a national hero. When he followed with summer victories at the British Games and the AAA championships, it seemed track officials and the press were ready to award him the Olympic gold medal right then and there. They praised his training as ‘exceptional’, an ‘object lesson’. Of his long, fluid stride, the British press gushed that it was ‘immaculate’ and ‘amazing’. He left rivals standing; he was a ‘will-o’-the-wisp’ on the track. After a race that left the crowd laughing at how effortlessly Bannister had won, a British official predicted, ‘Anyone who beats him in the Olympics at Helsinki will have to fly.’

Then the positive press turned quickly to the negative. Following his own plan, Bannister stopped running mile races at summer’s end. Tired from competition, he felt he had learned all he needed during the year and should now dedicate himself to training. When he chose to run the half-mile in an international meet, the papers attacked: ‘Go Back to Your Own Distance, Roger’. This was only the beginning of the criticism, but Bannister remained focused on his goal.

To escape the attention, he journeyed to Scotland to hike and sleep under the stars for two weeks. One late afternoon, after swimming in a lake, he began to jog around to ease his chill. Soon enough he found himself running for the sheer exhilaration of it, across the moor and towards the coast. The sky was filled with crimson clouds, and as he ran, a light rain started to fall. With the sun still warming his back, a rainbow appeared in front of him, and he seemed to run towards it. Along the coast the rhythm of the water breaking against the rocks eased him, and he circled back to where he had begun. Cool, wet air filled his lungs. Running into the sun now, he had trouble seeing the ground underneath his feet, but still he rushed forward, alive with the movement. Finally spent as the sun disappeared from the horizon, he tumbled down a slight hill and rested on his back, his feet bleeding but feeling rejuvenated. He had needed to reconnect to the joy of running, away from the tyranny of the track.

Throughout the winter of 1951–2, Bannister immersed himself into his first year of medical school at St Mary’s Hospital in London, learning the basics of taking a patient history and working the wards. He was, by the way, also training for the Olympics. By the spring he had developed his stamina and began speed work on the track. When he announced that he wouldn’t defend his British mile championship, the athletics community objected. It was unthinkable. He had obligations to amateur sport; he had to prove he deserved his Olympic spot; he must take a coach now; he couldn’t duck his British rivals. Bannister made no big press announcements defending his reasons, he simply stuck to his plan, trusting it. As isolating as this plan was, so far it had taken him exactly where he wanted – so far. Meanwhile, most other athletes trained under the guidance and direction of the British amateur athletics officials.

On 28 May 1952, Bannister clocked a 1:53 half-mile at Motspur Park with his ‘space-eating stride’. Ten days later he entered the mile at the Inter-Hospitals Meet and won by 150 yards. Maybe he knew what he was doing. The press turned to writing that he would silence his critics at Helsinki and that his training was ‘well-advanced’. Compared to those of the top international 1,500m men, his times were sufficient. His ‘pulverizing last lap’ would likely win the day. Even L. A. Montague, the Manchester Guardian’s esteemed athletics correspondent, trotted out to explain that Bannister was the ‘more sensitive, often more intelligent, runner who burns himself up in giving of his best in a great race’. Bannister was Britain’s best chance at the gold medal, and Montague wondered, ‘Do [critics] really think that they suddenly know more about him than he knows himself?’

Although he lost an 800m race at White City stadium in early July, the headlines exclaimed, ‘Don’t worry about Bannister’s defeat – he knows what he is doing!’ Ably assisted by the press, Bannister had painted himself into a corner. He was favoured to bring back gold by everyone from the head of the AAA to revered newspaper columnists – and, by association, by his countrymen as well. Of course, there weren’t going to be any scapegoats if he failed. ‘No alibis,’ as Bannister said himself. ‘Victory at Helsinki was the only way out.’ A part of him suspected that he had manoeuvred himself into this tight position on purpose. Come the Olympic final, he would have an expectant crowd, the rush of competition, two years of dedicated training, the expectation that it was his last race before retirement, and nobody to blame but himself if he lost. This was motivation.

By 17 July most of the British Olympic team had left for Finland, team manager Jack Crump declaring upon arrival in Helsinki, ‘We will not let Britain down.’ But, though he would have to join the team soon, Bannister was still in London. Like a few other athletes, he wanted to avoid the media frenzy in the prelude to the Games, and the inevitable waiting around, worrying about upcoming events. His friend Chris Chataway, the 5,000m hopeful, had also delayed his departure. The two scoured London for dark goggles to curtain the twenty-one hours of Scandinavian daylight. Given that one rarely saw the sun in London, it proved a difficult search. Bannister also sought out a morning newspaper.

It didn’t take him long to find a story headline – ‘Semi-Finals for the Olympic 1,500 Metres’ – that confirmed what Norris McWhirter had told him the day before about the added heat. ‘I could hardly believe it,’ Bannister later explained. ‘In just the length of time it took to read those few words the bottom had fallen out of my hopes.’ Worse, he had drawn a tough eliminating heat in the first round.

As he went about his day in the smog-choked London streets, the crisp air and fast tracks he expected to enjoy in Helsinki seemed threateningly close at hand. One could hardly have blamed him had he not wanted to go at all.