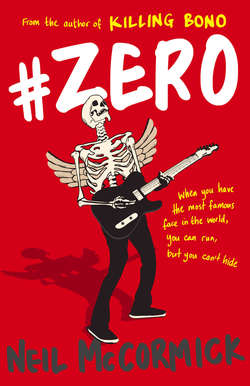

Читать книгу #Zero - Neil McCormick - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

7

ОглавлениеUp in my suite, I picked at a buffet without an appetite. A whole hour of unscheduled time to myself was almost unheard of – I should have been leaping for joy or, better still, catching up on sleep, but instead I was pacing the floor, listening to alternative club mixes of my next single, ‘Life On Earth’, at head-throbbing volume and flicking through channels on the wall-mounted flatscreen.

‘You should try and relax,’ Kilo shouted above the din.

‘Yeah, you got anything to help me?’ I fired back eagerly.

‘I think you’ve done enough,’ shouted Kilo.

But his job was not to question but to serve. ‘Enough is never enough!’ I yelled, as he tossed me a plastic pack of pills. ‘What are these?’

‘They’ll bring you down a bit,’ shouted Kilo. ‘Take two.’

I took four washed down with a tumbler of vodka. I felt the beat of the remix pound through me and waited for the wobble, the blurring of edges, anything to tune down the static fizzing through my mind. I watched the Starship Enterprise boldly go where no man had gone before, then pressed the remote and my own picture came up, news footage of my hyperactive exit from the press conference, some clips of Penelope and me from the trailer of #1 With A Bullet and a shot of Penelope and Troy at the Oscars where they seemed to be holding hands. How the fuck had I never noticed that before? Then there was some phone footage of me standing in the middle of traffic, reading the New York Post. Shit. Everyone was paparazzi these days. It cut to the photospread with all the offending bits digitally obscured. I snapped out of my trance and changed channel, only to wind up smack in the middle of a rerun of Darker With The Day, right on the scene where Penelope emerges from a swimming pool in slo-mo wearing that one-piece black swimsuit, water dripping down her skin, shakes her wet hair and looks right at the camera, that scene where everyone fell in love with her. She must have been younger than I am now and she already looked like she knew everything worth knowing, that she was everything worth knowing. I felt the first ripples of deep space open up in my chest and then it cut to Michael Douglas in mirrored aviator shades leering lasciviously, so I changed the channel and watched a crocodile with its mouth open while little birds fluttered in and out, picking at parasites between its teeth. The music was still pounding out. ‘And I wonder if you know just where you are? / In the palaces of Mars or a dirty astrobar?’

There had been some strategising on the ride back about how to handle the Penelope crisis, and another failed attempt to reach her on satellite phone. Irwin Locke stuck to the line that the film crew were doing deep jungle location work and were temporarily uncontactable. Well, I knew exactly what kind of deep jungle work that faithless bitch was interested in. He said there were plans to send a chopper in. Oh, I’d send a chopper all right, I’d send a chopper to chop off her head. My voice sang out in stereo, swimming around my brain, ‘It’s a blessing, it’s a curse / So beautiful it hurts / Do you believe … in life on earth?’

I lurched into the bedroom, lay down and tried to get the images out of my mind but it wasn’t working. All I could see were endless permutations of Penelope and Troy and Eileen fucking like monkeys on heat, and what the fuck was Eileen doing in there anyway? She was way out of her league getting it on with a couple of Hollywood superstars.

Last time I saw Eileen, she was standing in my old man’s living room in Kilrock, crying her eyes out under the painting of the sacred heart of Jesus. She had just given me a blow job in my bedroom, and then I told her I wouldn’t be coming back any more, and that I cared for her and would always care for her but that it was over, over, over, Kilrock was too small for me, I had places to go, things to do, and I was leaving the past behind for good. It was after that last shitty visit to London when she turned up with a big red suitcase and caught me with a couple of groupies in my hotel room, after the abortion, after that terrible, terrible day lurking outside that fucking awful clinic, not knowing if I was worried for my babe or sick for my unborn baby, or just feeling utterly nauseated at having come that close to being sucked into a life of domestic drudgery just as I was reaching escape velocity. I had hooked up with Beasley by then and made up my mind to split the band. The Zero Sums had returned from a European tour in disarray, nobody was talking to me anyway. I went back to Kilrock to get my things and break some hearts. I didn’t care if I never set foot there again. I didn’t have the courage or the meanness to tell Eileen before. Or maybe I was just greedy and wanted to feel her going down on me one last time.

Actually, that wasn’t strictly the last time I saw her. Cause my brother Paddy came in and looked at me like I was dirt, and said he’d take Eileen home. I watched from the window as they got into Paddy’s car, a beat-up piece of rusting shit that he treated like it was a fucking latest model BMW. And she looked back up at the tenement at that very moment, and saw me, and blew a kiss, and shook her head, like I was making the biggest mistake I would ever make in my life, and then I ducked behind the curtain. And that really was the last time I saw her.

I’ve never been back to Kilrock, not even to visit the old man in his new house on the hill, bought on the advance for my first solo album, or Paddy in his little boutique hotel, paid for by my first American number one. I heard Eileen left soon after. Went to live in Dublin, or maybe it was London. Cut herself off from everybody, her own family, her old friends, and I can’t blame her. There was really nothing for people like us in that fucking town.

It was actually a relief when Kilo came in with a call from Flavia, anything to stop the memory-jacking. He handed me a bottle of water with the phone, then practically tipped my head back and poured it down my throat. Flavia proposed a damage-limitation exercise on Kitty Queenan, a half-hour exclusive interview, during which I would let it be known the pictures were just movie out-takes and melt her heart with tales of how hard it was being subjected to pernicious media assaults. ‘Give her the full charm offensive,’ instructed Flavia.

‘I’ll charm her fucking pants off,’ I said, although I was worried my head was starting to float away from my neck.

‘Are you fit to do this?’ Flavia wanted to know. ‘Put Kailash on.’

Kilo spoke briefly into the phone, assured her I was fine, then chopped out a couple of lines. I greedily snorted them both. ‘One of them was for me,’ sighed Kilo. But I was feeling better already, if you discounted the slight twitch in my left eye. I put my mirror shades back on.

Kitty wanted to interview me in my suite for the full at-home-with-a-superstar experience, hotels being as close to home as most superstars ever get. Kilo let her in, made sure we were plentifully supplied with hot coffee and iced water, then made himself scarce. My interrogator appraised the room with a sweeping gaze that seemed to suck in every detail before coming back to rest on me. For someone who should have been physically unimposing, a short, middle-aged woman swathed in a jumble of lace, patterns and costume jewellery, I was struck again by her aura of mischievous sharpness, as if the frumpy glamour of loud make-up and clashing layers was a disguise, something to blur her dangerous edges. When she was done admiring the hotel artwork and contents of the jellyfish tank, we settled on either side of one of the elongated sofas, digital recorder perched between us, notebook in her lap.

‘Would you mind taking your sunglasses off?’ she enquired.

‘I don’t think so,’ I said, while she warped in front of my stoned vision, a wolf in hippie clothing. There was something intimidatingly sensuous about such ripe confidence. Her eyes were predator sharp, and when she spoke, I got the uncomfortable feeling I might be the main course.

‘This business with Penelope and Troy is obviously bothering you, yet it goes with the territory of celebrity unions, so … what is it about this particular story that has upset you so much?’

‘I wouldn’t say I’m upset,’ I lied. ‘Take the celebrity out of it, I’m just a guy in love with a girl, hearing horrible things said about her …’

‘Can we really take the celebrity out of it? I am not sure you are just a guy, and she’s certainly not just a girl, she’s one of the most famous women in the world, and there is a twenty-year age gap. She is old enough to be your mother…’

‘You’re old enough to be my mother,’ I pointed out.

‘Not quite,’ she retorted, a little wounded.

‘Half the women I meet are old enough to be my mother,’ I said, to smooth things over. ‘Usually the most interesting half. I’m drawn to character, I’m drawn to experience – girls my own age have nothing to teach me.’

‘Your own mother died when you were young, didn’t she? I notice that you never talk about her.’

‘I don’t actually remember her,’ I said. ‘I was very young.’

‘Nine is not that young.’

Fuck, she was tough. ‘I think I was eight,’ I said. ‘My father was the dominant character in my life, anyway. He raised me really.’

‘So would you say he was both mother and father to you?’

I laughed out loud. ‘No, I wouldn’t say he was a mother at all. Not much of a father either, sometimes. He was just my old man. He was what I was running away from when I ran into music. I wanted to find something I could make my own, a place where I was safe, and music was that place.’

‘A kind of womb,’ she suggested.

I didn’t like where this was going at all. ‘A womb with a view,’ I joked, trying to divert her. ‘And the view was the whole world. Music wasn’t just about cuddling up somewhere nice and warm, it was about getting out in the world, getting away from Ireland, seeing new things, having new experiences, meeting new people, like you. Smart people, educated people, people I could relate to. That’s a nice dress.’ I reached forward and touched the fabric of her billowy frock. There was a trace of a blush in her cheeks but she wasn’t deflected for a second.

‘Thank you,’ she said, smiling indulgently. ‘So do you think the fact that you never really mourned for your mother has shaped your attitude to women?’

Fuck sake, she was like a dog with a bone. ‘I am sure I mourned my mother,’ I said. ‘Everybody has to bury their parents eventually. Death’s part of life, that’s what my old man used to say.’

Was it? Did he really say that? I don’t know where that came from. I don’t remember him ever talking about death at all, certainly not my mother’s.

‘Look at the orphans in MedellÍn, they’ve got nobody, but they survive, living on the streets, fending for themselves, it’s what you do, that’s what being “never young” means. You’re forced to grow up fast.’

‘When you were having your photo taken this afternoon, my photographer, Bruno, asked about your mother’s family …’

She didn’t miss a trick. ‘My mother didn’t have any family. We were her family. I am her family.’ I could feel panic rising – it was time for desperate measures. I reached out and touched her arm. ‘Why are you so interested in my mother?’ I said.

‘Maybe because you don’t seem to be.’

‘I don’t think about her very often,’ I said, and reached forward and turned off her recording device. ‘Can we go off the record for a minute, is that OK? If I wanted to go to analysis, Manhattan’s full of shrinks. And they’ve got diplomas from medical school, not journalism courses. I just don’t believe in navel-gazing. Music is therapy and I’ve got music coming out of every orifice. I can fart and it sounds like a symphony. Please don’t quote me on that.’

‘Are you trying to be obnoxious or does it just come naturally?’ said Kitty, with a sly, mocking smile.

‘I’m just kidding with you, you make me nervous,’ I said, gently stroking the back of her hand and holding the tips of her fingers. I picked that move up a long time ago. If she pulled away, I could pretend it was just a friendly gesture. But if she lingered, we both knew it was on. The truth is, they never pulled away. Not any more. So I was a bit flummoxed when she reached forward and turned the recording device back on.

‘Why would you be afraid of a few questions, you’ve been batting them back like a pro all day?’ she said. ‘I’ve been watching you. You don’t let anyone under your shield.’

‘It gets exhausting talking about yourself all the time,’ I pouted, caressing her fingers again. ‘Why don’t you tell me what you think about me instead?’

‘Oh, I think I better save that for my readers,’ she smiled. ‘When was the last time someone said no to you?’

‘I’ve got a feeling someone just did,’ I said, letting go her hand. The woman confused me. I was usually good at this. But I couldn’t tell where her questions where leading, or how to bamboozle her with my bullshit.

‘Are you happy, Zero?’ she asked, with a quiet intensity that left me reeling behind my shades. I felt her warp in my vision again. This time she didn’t look like a wolf in sheep’s clothing, she looked like the holiest little sheep you ever saw, as meek and mild as the lamb of God itself, soft bright eyes dewy with concern for my well-being. Maybe I had taken too many drugs.

‘What kind of question is that?’ I retorted, my mouth dry.

‘One that people ask themselves all the time,’ she said.

‘I’ve got everything I ever dreamed of,’ I said, getting up to refill my vodka glass. ‘I’m only twenty-four, for fuck’s sake.’

‘Twenty-five,’ she corrected me. Jesus fucking Christ, where does the time go? I was getting old. Pop stars are like dogs. Every year counts for seven.

‘I’m ludicrously rich,’ I continued, making a joke of the whole thing. ‘I’m ridiculously famous, engaged to the most beautiful woman on the planet. And you’re asking me where it all went wrong?’

‘That’s not what I asked,’ she smiled. ‘But let me put it another way. When was the last time you clearly remember being happy?’

I stood gawping like a beached fish, my mouth dry despite the swill of vodka. I could see stretched reflections on the surface of the jellyfish tank, where luminous, transparent blobs drifted blindly in their liquid element. Outside, through slanted blinds, my billboard loomed in the sunlight, giant eyes following my every move. All the while, Kitty sat calmly absorbing my discomfort, quietly scribbling in her damned notebook. I was supposed to be charming her, seducing her, recruiting her to the cause, but I couldn’t even talk to her. I knew I needed to give her something. So I just told her the first story that came to mind.

‘When my brother and I were small, I don’t know what age, we mitched off school,’ I said. ‘It was a beautiful day, just like this one, the sun was out, and we just couldn’t stand the idea of being cooped up indoors.’ Where was this story coming from, suddenly so vivid in my mind? ‘I don’t know whose idea it was – probably Paddy’s, he was older – or what we were doing, really, roaming about the hills, we were going to get into so much trouble. But then the strangest thing happened. I don’t think I’ve ever told this story to anyone. You’ll have an exclusive. There was this truck, rattling along in the middle of nowhere, on the road down below us, we weren’t paying it much attention, but suddenly it jack-knifed. I don’t know what happened, maybe the driver fell asleep, maybe its wheels went into the ditch along the side, maybe it hit something, but it just tipped right over, crash, came skidding to a halt below us.’

Kitty looked up at me curiously. But I didn’t feel like I was talking to her any more. I was just remembering, with a sense of wonder. ‘It was a pretty remote place, Kilrock. There was nobody around, just us and some sheep and this fucking truck lying on its side. I didn’t know what to do. I was only little. But Paddy ran down, he didn’t hesitate, he clambered right up on the side of the thing, and he got the door open, and he was calling me to help him, but I don’t know what help I would have been, I was just a lad. Paddy wasn’t much bigger himself. Next thing, he’s pulling this guy out. He’s all bloody and dazed, the driver, but Paddy gets him out. He gets him down. I just stood there watching. I was terrified. The truck is on fire now. Paddy’s dragging the guy as far from the truck as he can, like it’s going to blow up, like in the movies. It didn’t blow up but that cab was burning, the flames were licking everything, he’d have been gone for sure if we hadn’t been there, mitching off school. So he has a phone, and we call the police, and soon the place is crawling, there’s an ambulance and fire truck, everybody’s there, even the headmaster, and we’re like these great heroes. You saved his life, boys! You saved his life. We got a medal, I think. Or anyway, there was some kind of presentation in the school hall later, like a while later, a couple of weeks, with the mayor and all. And that’s what I really remember. Cause it was the first time I’d ever been on stage. That’s the truth. The first time I’d ever been up there with people applauding and flash lights going off from photos being taken. It was in the papers. The guy’s whole family had come. Jeez, even my dad was happy, and he should have been tanning our backsides for skipping school. And I was happy on that stage, really happy, I remember that. I felt like I belonged up there. It was electrifying, standing above the audience, looking down at them, while they’re clapping and cheering. Electrifying. Still is. But you know what else I was thinking, the whole time?’

I waited. I had her now. And if she asked, I’d tell her the truth. ‘What were you thinking?’ she finally said, breaking my stage-managed silence.

‘I don’t deserve this,’ I said.

She smiled sympathetically. That’s when I knew I had her. Still, she had to push it. That was her nature. ‘Was your mother there?’ she asked.

‘I don’t remember,’ I insisted. But she must have been, mustn’t she? You’d expect your mother to be there, on the greatest day of your life. But maybe she had vanished already by then, faded out of my life, as if she’d never been there at all. Just a black hole, where love should have been.