Читать книгу I Wish to Die Singing - Neil McPherson - Страница 7

ОглавлениеPreface

Yes Hay chem.

I am not Armenian.

I was born in London. My dad is Scottish, my mum is a Londoner. My only link to Armenia is that one of my best friends at school happened to be Armenian – in the same way that other friends at school might wear glasses or have ginger hair. We certainly never discussed the Genocide back at school.

The only connection that I have to Turkey and the Ottoman Empire is through the Gallipoli campaign – the Allied invasion of Turkey on 25th April 1915, the day after the start of the Armenian Genocide. Two distant cousins from my dad’s side of the family, Eric Young and Archibald Templeton, were both killed in action on the same day. On my mum’s side, my great uncle Bernard went ashore on ‘V’ Beach on the first day of the landings, and was killed in action six weeks later. He was twenty-five years old. For years afterwards, my granny – already an orphan when her big brother was killed – cried for him every Remembrance Sunday.

Grasping at straws, my great-granddad was a Scottish Gaelic speaker. Perhaps a Jungian might argue that I have some residual folk memory of the aftermath of Culloden or the Highland Clearances, but that would be both tenuous and pretentious. The simple truth is that I have no connection with the events of this Genocide or any other. It wasn’t a surprise, then, that so many people wanted to know the reason why I chose to write this play. If it had been any other historical event, I would have been chary about appropriating someone else’s story, but the Armenian Genocide is different. As it has consistently been denied by the Turkish government for years, it made sense to attempt to tell the story of the Genocide and its aftermath as someone who was not Armenian – as someone with no vested interest of any kind. I received nothing but support from the Armenian community, both in the UK and abroad.

As far as I remember, the first time I ever heard about the Genocide was when I was eighteen and read Tim Cross’ The Lost Voices of World War One which included the work of three leading Armenian poets, all deported from Constantinople on April 24th 1915.

Seventeen years later, as Artistic Director at the Finborough Theatre in London, I was programming the theatre for the 2005 season. As usual, I researched the anniversaries that fell in that year as they can sometimes be a useful marketing hook for a production. When I learned that 2005 was the 90th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, I decided to search for a play that we could produce to commemorate it. All of the plays I could find were by Armenian-Americans. Most were very short (Aram Kouyoumdjian’s short play Protest became the closing section of the first incarnation of I Wish To Die Singing), and focused on the experience of the Armenian diaspora in the United States. They all assumed that their audiences already possessed a good working knowledge of the Genocide.

But I quickly learnt that the Armenian Genocide was very far from common knowledge. Most people I spoke to had never heard of it. A very few had, but only vaguely, and then solely in relation to the Holocaust, rather than as an event in its own right. It was then that I started to learn about Turkey’s ongoing denial of the Genocide. I soon found myself reading all the evidence I could find to see if there was any merit in what the Turkish government insist on calling ‘the other side of the story’, so that I could make up my mind for myself.

In the end, it wasn’t the horror of the Genocide itself which forced me to try and tell this story, but Turkey’s denial of it – the lies in the face of incontrovertible evidence, the evasions, the half-truths, and the febrile desperate efforts to shift responsibility on to the victims. Denial is truly ‘the final stage of genocide’, but so too is the betrayal of the Armenian people by the rest of the world, and the pusillanimous reaction of the international community – especially the UK – to recognition. I needed to scream about how these wounds, hurt, anguish and grief were all intensified because of a blank-faced refusal to tell the truth. And if I wasn’t able to find a play that would do that, then I vowed to try and create one myself.

Normally, I would have just commissioned a playwright to write something for us, but I knew that I wanted something more than just a fictional domestic piece with the Genocide as a plot twist in Act II. And I had already done the research. Hubristic or not, I wanted to tell the whole story as simply and honestly as I could, and wherever possible using the words of the people who were there. The most authentic way I could think to do that was a hybrid of history lesson and documentary drama and verbatim theatre – and for it to be unashamedly agitprop. Agitprop theatre has become deeply unfashionable, but, for an event which was so unknown and where the facts were so stark, it seemed the only truthful way of presenting the story. A theatre production in an intimate Off West End theatre is never going to change the world. But I needed to at least try.

I called my old school friend who, with his customary generosity, lent me some rare books to get me started, and despite some death threats (always a sign that you’re doing something right), the 2005 production completely sold out its few performances. I decided to wait until the centenary in 2015 before doing it again so that we could open the production on the exact anniversary of the start of the Genocide – 24th April. For it, I wrote a radically different new version of the script, making full use of the hearteningly vast amount of additional research which had been published in the ten years since 2005, and trying to make the play as topical as possible. Our month long run saw the centenaries of both the Genocide and the Gallipoli landings, as well as the UK general election and continued atrocities by Islamic State, and so I also included a sequence that was updated for every performance so that the play would always be as up to date as possible.

The play is based entirely on published sources, drawing heavily on the memories of eyewitnesses, primarily those collected over many years by the Armenian ethnographer Verjine Svazlian. Turkey’s denial of the Genocide has moved over the years from a bludgeoning denial to an increasingly sophisticated use of very well paid academics to dissect and dismiss all of the primary sources, and so I started out being as scrupulous with my sources as possible, quoting them verbatim and in full. Any manipulation of the material for theatrical purposes might mean that the truth of the piece would be questioned by the denialist lobby. I soon found though that if I included everything I would have liked to, the play would have lasted for days. I always felt that the play should last absolutely no longer than ninety minutes, with no interval or no curtain call, so that it could be a hard-hitting salutary shock without allowing the audience the excuse of ‘compassion fatigue’.

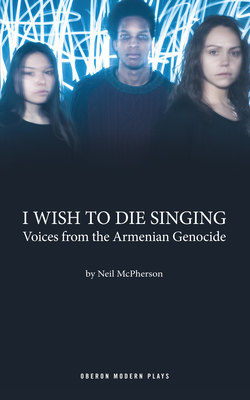

As every source that deals with the Genocide is dismissed as ‘forgeries and falsehoods’, and it would make no difference how careful I was, I eventually accepted that some changes to the material to make the piece dramatically viable were necessary. Given the time constraints and the multiplicity of material, I conflated the stories from many different survivors into the stories told here. It was not a deliberate decision to focus the play around the memories of three children. I was concerned that it might be seen as manipulative or even precious, but the most interesting and affecting testimonies I found were from survivors who were children at the time of the Genocide, and I was anxious to avoid an evening made up of elderly survivors speaking entirely in the past tense. I therefore transposed the testimonies into the present tense to make it more dramatically alive, and allowed myself a little dramatic licence in expanding the back stories for Gayané and Souren. It was a fortunate coincidence that the best actors we found for the children’s parts were three performers from very different ethnic backgrounds which added resonances not originally in the script.

Internationally, the denialist lobby were careful to keep their heads down in the run up to the centenary, and so we were able to present the 2015 production without any death threats. The reaction of the Armenian community was overwhelming, including parents bringing their children, and even people who travelled especially to the theatre from as far afield as Beirut and Yerevan to see it. On the other side, a Turkish acquaintance wrote a lengthy polemic on my Facebook wall (along the lines of ‘it never happened and they asked for it’) and then summarily unfriended me. A lady insisted on handing out leaflets denying the Genocide at some performances. The most negative reaction we received wasn’t about the Genocide at all, but an email vehemently complaining that the play criticised Israel’s continued refusal to recognise the Genocide. We did however receive some quite spectacular abuse on social media, which is where not being Armenian myself really came into its own. The first accusation would invariably be ‘What can we expect? You’re just a ‘LIARMENIAN’ (Genocide deniers seem to have something of a penchant for using block capitals) and were shocked to learn that no, I wasn’t, not at all. Their second accusation would usually then be that I was obviously a sell-out and the whole production had been paid for by Armenian money. To which the answer was – with no pun intended – ‘I wish’. After that, they usually moved on to suggestions that were mainly scatological and probably anatomically impossible, but which worked very well when I quoted them verbatim in the play itself.

I would like to thank the companies of both the 2005 and 2015 productions of I Wish To Die Singing and their directors Kate Wasserberg and Tommo Fowler; the staff and volunteers of the Finborough Theatre; Bianca Bagatourian of the Armenian Dramatic Arts Alliance; Philip and Christine Carne; James Graham; James Hogan and all at Oberon Books; Aram Kouyoumdjian; Bernard Nazarian; Misak Ohanian of the Centre for Armenian Information and Advice; Rafik Sarkissian of the Armenian Genocide Centenary Commemoration Committee; Sévan Stephan; Pier Carlo Talenti of the Center Theatre Group; and, above all, to Jane.

And if you still might be wondering the reason why a non-Armenian felt compelled to try and share this story, the last word should go to the poet Peter Balakian:

‘If the extermination of a million and half people and the erasure of a three-thousand-year-old civilization isn’t important enough to write about, what the fuck is?’

That’s reason enough.

– Neil McPherson, London, September 2015