Читать книгу Cold Blooded Evil - Neil Root - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE DAWNING OF DISBELIEF SATURDAY, 2 DECEMBER 2006

THORPES HILL, HINTLESHAM, SUFFOLK

11:50am

ОглавлениеThe Suffolk landscape in winter can be very beautiful, the falling leaves gently rustled by the wind a reminder of time passing and the inevitability of the life cycle. The bare branches of centuries-old trees stand in haunting silhouette against the white sky. This is the real English countryside, where the rustic majesty of the fields is richly veined by meandering brooks and streams. In such a tranquil setting it is easy to forget about the essential violence of nature.

The small village of Hintlesham is to be found about 7 miles (11.3km) to the west of the town of Ipswich. Although clustered around a main road, this is a quaint and simple place where little changes, and when it does, much comment is aroused. On an ideal summer’s day, parts of it can be chocolate-box perfect. Not the obvious place for a macabre discovery.

Trevor Saunders was doing his regular round of inspection that morning around the Thorpes Hill area. Employed by Hintlesham Fisheries, he knows every metre of his stretch. Mr Saunders would later say:

‘I was doing my normal patrol along Burstall Brook to check on any blockages when I noticed two round, smooth surfaces sticking out of the water, which I later found was the woman’s bottom. Initially I thought it was a dummy. I went into the brook to make sure and, on further investigation, found it was a body. It was face down, under water. I had to move a little bit of debris to make sure it was a body. Then I phoned the police.’

The tranquillity of the scene was soon shattered as the police closed off the crime scene and surrounding area and conducted the usual thorough forensic examinations and photographs before the body was taken away.

The next day Suffolk Police made a statement confirming the identity of the body. She was Gemma Adams and she had lived at Blenheim Road, Ipswich, just on the outskirts of the town centre itself. She had been reported missing by her partner over two weeks earlier on Wednesday 15 November, when she failed to return home in the early hours of the morning. Gemma had worked as a prostitute, primarily to fund a serious drug habit. On the night of her disappearance she had gone to work on the streets of Ipswich’s red light district.

A police spokeswoman confirmed that the death was being treated as ‘suspicious’ and that the post-mortem had not established any definite cause of death.

Appeals for information started immediately. The police knew very well that the first 48 hours after the discovery of a crime are crucial – any witness statements, crime scene evidence and possible leads would be fresh. As Gemma’s body had been stripped before being left in the water, the police knew how urgent it was to find her clothing and other effects. Developments would soon be forthcoming on this front, but few strong leads to the possible offender.

It was a shocking day. Suffolk does not have a high crime rate, despite having had some high-profile cases over the years. These were exceptions, not the norm. In a 2004 Suffolk Police survey, 45 per cent of Suffolk residents questioned felt safe where they lived and only 17 per cent were worried about violent crime (Source: Suffolk First, June, 2004). Compared with similar surveys carried out in other parts of the country, these figures are good.

But murder can occur at any time and in any place. Human nature does not take geography into account when entering dark recesses of the mind. General trends can be followed, with urban, more deprived areas more likely to experience violent crime. Although murders can almost always be profiled geographically, the mind of a killer is as random as any mind, especially if there is a sexual motive.

The finding of Gemma Adams made the front page of the Ipswich Evening Star. While shocking and saddening to the community, it could have been an isolated prostitute murder, a phenomenon we will discuss later. But there was no getting away from the callousness shown in the way Gemma Adams was dumped. The lack of respect and compassion, the indignity of being left naked, lying face down, in little more than a ditch. What kind of evil could be behind this?

Unfortunately, it was only the beginning. Surrounded by sleepy villages and traditional agricultural land, Ipswich is the county town of Suffolk, with a population of 140,000 people in 2006. Looking like many a provincial British town of the twenty-first century, with the predictable chain stores and shops, gradually losing individual identity as the years pass, it is now an expanding commercial centre. Yet there are still many historical points of interest, even if it lacks the excitement and glamour of a major city or the magnetism of a cathedral city.

Founded at the tip of the Orwell estuary, the site on which Ipswich stands has been inhabited since the Stone Age. Like many other places, the river that runs through it was always an important trade route. The River Orwell is also well known for giving a young aspiring writer named Eric Blair his new name in the early twentieth century. He would of course become the internationally respected author George Orwell.

During the seventh, eighth and ninth centuries the town was known as Gippeswic. It was actually the first and most famous Anglo-Saxon port and one of the most important trading communities in the country.

There are many surviving traces of the medieval period in the town, from the layout of the streets to a number of historic churches from that time. The major industry of the town in this period was the very lucrative trade in Suffolk cloth, but this market went into sharp decline as England moved into the Georgian period, and this lack of prosperity helps to explain the fact that there is little Georgian architecture in Ipswich.

In the early twentieth century, the largest wet dock in the Europe of the time was built there, and along with rail transport links for trade and the setting up of new industries during the Industrial Revolution, Ipswich was pulled into the modern world. This return to economic prosperity in turn produced much building in the Victorian period and many fine examples can still be seen in the town today.

The two World Wars of the twentieth century hit the town hard however. The excellent rail network, engineering works and the port were prime targets for German bombs. In the First World War several Zeppelin raids led to the destruction of many buildings, and in the Second World War the Luftwaffe carried out over fifty bombing raids over the town, which sadly resulted in dozens of deaths.

Football has long played a major part in town life, with Ipswich Town FC its focus, operating from the Portman Road stadium. The club can boast that it had the 1966 England World Cup winning manager Sir Alf Ramsey at the helm from 1955 until 1963. Ramsey took Ipswich Town to the top of the game, winning the First Division title in 1962. The pride and affection in which he is held are best symbolised by the elegant statue of him outside the ground. Ramsey continued to live in Ipswich until his death in April 1999.

All of these layers of history help to explain the sense of community to be found in Ipswich. The Suffolk character is simple and direct in the best possible sense. Honest, loyal and stubborn, the native Suffolk people embody the characteristics of an ancient community which has seen much change, but the direct approach to life has been passed down from generation to generation. The people of Ipswich tend to take people at face value until given a reason not to, but there is an underlying core of shrewdness that should not be underestimated.

Through the addition to this native character of late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century immigration, a collective identity and a unique spirit have been forged. There is a definite provincial air in Ipswich, a feeling of self-reliance built through a tumultuous history. More intimate than a larger town or city, people communicate more and know more about each other. There is a feeling that there would be a ‘pulling together’ of the community in the face of collective adversity. This would be proven to be the case over those horrible weeks in December 2006, when at various moments time seemed to slow down, stand still and then race along.

For any loving parent, the death of a child is too frightening to imagine and even more painful in reality. When that child has predeceased a parent through a violent act, the hollow sense of loss is further complicated by powerful feelings of anger, frustration, bitterness and sometimes guilt. The cold reality of day is exposing and cruel. The parents of Gemma Adams now experienced this onslaught of emotions.

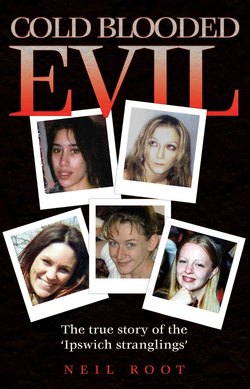

Like many parents they described their daughter as ‘bright and bubbly’ in media interviews. And photographs of Gemma certainly support this description. Blonde, blue-eyed and with a peachy complexion, her sweet smile makes her seem younger than her twenty-five years. She certainly does not look like the popular preconception of a prostitute, but then Gemma’s background was very different from that of the ‘average’ prostitute.

In an interview with the Daily Telegraph on 12 December 2006, ten days after Gemma’s body was pulled from Burstall Brook, her father Brian Adams expanded on his feelings for his daughter: ‘We never knew she was working as a prostitute until she went missing. It’s just every parent’s worst nightmare. If we’d known, we would have done everything in our power to stop her, just like we tried to get her off drugs. But I don’t want people to think of her only as a prostitute. The Gemma we want to remember was a loving, beautiful and wonderful girl.’

These are the moving words of a loving, heartbroken father, but of course the word that stands out is ‘drugs’. And an examination of Gemma’s upbringing makes her descent into addiction and then prostitution even more tragic. There were no underlying factors that could have predicted the route of her life. It must be remembered too that if she had had the chance to live, she may well have taken a better path in the future.

The Adams’ family home is a large detached house in the wealthy village of Kesgrave, on the eastern fringes of Ipswich. Brian and Gail Adams have two other children apart from Gemma and they have all been brought up in a comfortable and loving environment. Gemma was always an animal-lover, very close to the family’s pet dog Holly, and a keen horse rider. Like many young girls, Gemma was also a Brownie and thrived on group activities. As well as this she took piano lessons. It would be almost impossible to paint a rosier family portrait. There were never any signs in her childhood of what the future held for Gemma and she seemed destined for a bright future.

At the age of sixteen, Gemma left Kesgrave High School, where she had been a popular student, and entered Suffolk College in Ipswich, a major educational and vocational training institution. Gemma completed a GNVQ course in Health and Social Care there.

But small cracks were beginning to appear in her life and her parents are sure that it was at about this time that she fell in with ‘the wrong crowd’. In the Sun newspaper on 13 December, her father Brian said: ‘She had everything going for her, yet at some point she was offered drugs, and it went from there.’

It seems that Gemma graduated from cannabis to heroin, and became quickly addicted. While the tabloid media tends to emphasise the link between these two drugs and liberal opinion likes to dissociate the two, in Gemma’s case there was a definite escalation.

After leaving college, Gemma got a job at a local insurance company. But it was at this time in her early twenties that her heroin and crack cocaine addiction was beginning to take a firm hold. Her dependency soon became public knowledge at the insurance company as her attendance record rapidly worsened and when she was in the office she was sometimes not in a suitable state to fulfil her duties. She was eventually fired from the company in 2004.

This probably cut her final tie to the conventional life that she had aspired to as a girl and had been brought up to aim for. An addict needs their next fix and desperation usually leads to two well-trodden routes: burglary and prostitution. It seems that Gemma now took the latter option. By now Gemma was living away from her parents in rented accommodation in Ipswich with her boyfriend.

Her parents made numerous attempts to get her off drugs, but they could not get through to her. Eventually they lost all contact with her. Their frustrated and loving need to help her was now permanently thwarted.

In the same interview, Brian Adams, fifty-three, said: ‘Once your child is involved in hard drugs, your heart is already broken. It’s just like we’ve been in a nightmare and even closing your eyes does not give you relief. You close your eyes and it’s still there. Normally, if you have a nightmare, you wake up and the pain is gone, but this nightmare is ongoing.’

A moving tribute to Gemma was left on a local Ipswich newspaper’s website during those terrible days. The poster was Gemma’s sixteen-year-old brother Jack: ‘Gem, you will never be forgotten. I know you’re in a better place now, and I’ll always love you. There is now a massive hole in our family that will never be filled.’

Touching words from a close-knit family now estranged from their beautiful sister and daughter forever. Her father Brian summed it all up in the Sun on 13 December: ‘We are going through Hell. We are just praying that the madman who did this is caught soon.’

On the night of Tuesday, 14 November, Gemma and her boyfriend had left their home in Blenheim Road on the edge of Ipswich’s red light district. They walked into one of the areas of the district where Gemma did business. She was soon alone on the streets. After the discovery of her body on 2 December, a witness came forward with the last known sighting of Gemma. This was at 1.15am on Wednesday 15 November outside a BMW car dealership on West End Road, close to the junction with Handford Road. The latter is a major road close to the Portman Road football stadium.

Gemma was reported missing at 2.55am, an hour and forty minutes after the last sighting. Her boyfriend Jon Simpson called the police after she had failed to respond to two text messages he had sent to her mobile phone. It would be seventeen days before her body was found 7 miles (11.3km) away.

The streets where Gemma spent her last free moments are tough ones. They are almost a universe away from the affluent village of Kesgrave where she was brought up. This network of streets near to the football ground would come under increasingly intense scrutiny over the following weeks. The spotlight would be firmly on this home of Ipswich subculture.

The red light district of Ipswich is situated to the west of the town centre itself, around the Portman Road football ground. The street that leads into the area from the main shopping centre has a seedy, neglected atmosphere. There are takeaway restaurants, tattoo and piercing parlours and small grocery shops. But the actual red light activities take place slightly further to the west, in what is primarily a residential area.

The houses here are in a variety of architectural styles, ranging greatly in size, age and price. A small network of streets and roads that are connected to and run between London Road, Handford Road and West End Road make up the red light area. London Road and Handford Road are also part of the A1214, which leads out of Ipswich and has good links to the A14 and A12. In this sense it is a crossroads area in and out of the town.

In the nineteenth century, when Ipswich was a busy port, there were almost forty brothels in the area, but there is nothing like that now. The overwhelming activity now is that of street prostitution and this is, as always, linked with drug dealing. A local resident of the Ipswich red light district says: ‘I live in the red light area of Ipswich and regularly overhear early morning exchanges between local prostitutes, their dealers and the odd client.’

Of course, most of the kerb-crawling takes place in the twilight and dark and on most nights the classic image of a prostitute leaning into a car window can readily be seen. There are between thirty and forty prostitutes who regularly work in this area, despite police operations having cleared some streets.

Societies throughout history have never found a long-term solution for what is often called ‘the oldest profession’. The dangers faced by these vulnerable women (and sometimes men) are massive. There are the obvious dangers of physical attack and sexually transmitted diseases, but also the hidden risks of psychological damage. The trigger for entry into ‘the game’ is usually desperation for money. But there are other factors that keep prostitutes working: a single parent needing to support children, fear of violence from a pimp or trafficking gang, and drugs. It is the last of these that saturates this story.

Drug addiction, specifically of the Class A kind, is a terrible sickness. The habit must be fed, the next fix paid for by any means necessary. Sometimes a habit can be exorbitantly expensive, and the relatively high and immediate payment that prostitution offers is often the only way an addict feels they can survive. Drug dealers are only too aware of this and so where there are prostitutes there are usually drug dealers, and vice versa. This is the case in the red light district of Ipswich.

If drugs are the root cause of much prostitution, then that is the problem that our society has to tackle. Especially in a rich country such as Britain – collectively as a nation we have let these human beings down. Vulnerable and fragile people cannot survive intact in a harsh, predatory environment; a snowball does not stand a chance in an oven.

According to Home Office figures, sixty prostitutes are known to have been murdered in Britain in the decade between 1996 and 2006 – an average of six a year, or one every two months. In 2006 alone, there were 766 known murders in Britain and 2.4 million violent attacks. The UK achieved an impressive murder conviction rate in 2006 of over 75 per cent. But the UK murder conviction rate where the victims were prostitutes was only 26 per cent for the same year.

On the very day that Gemma Adams took her last walk to work in Ipswich’s red light district, Tuesday 14 November 2006, there was a news item on page fifteen of the Ipswich Evening Star, the headline reading ‘Campaign on Prostitution a Failure – Claim’. Gemma would be reported missing within hours of this edition of the newspaper going on sale.

As recorded on the Ipswich Labour Party’s website, a survey had been carried out in August 2006 by Labour Party councillors and Chris Mole, MP. The results showed that ‘90% of people living in and around Ipswich’s red light district said their lives were affected by street prostitution’. Prompted by this finding the Labour Group called on Ipswich Borough Council, Suffolk County Council, the primary care trust and Suffolk Police to crack down on street prostitution.

Three months later, the leader of the Labour Group, Councillor David Ellesmere, reported that ‘the response had been disappointing’.

Councillor Ellesmere said: ‘Leading politicians at the borough and county councils do not appear to have taken much interest in the issue. There has been little or no action on the majority of our proposed programme. No mobile CCTV cameras have been deployed, there’s been no commitment to a programme of alley-gating, no improvement on reporting procedures for prostitution and kerb-crawling, no increase in cleaning resources or improvement in reporting procedures for needles and condoms, no increase in the use of ASBOs (Anti-Social Behaviour Orders) for offenders and no extra help to get women out of prostitution or increased drug treatment.’

Councillor Ellesmere did however reserve some praise for Suffolk Police, saying that visible patrols had increased and some plain-clothes work had started. This was the state of affairs when Gemma Adams disappeared.

In the Guardian newspaper of 22 March 2007, Liz Harsant, the leader of Ipswich Borough Council, was reported as saying: ‘The red light district is actually a nice residential area and many of the residents have had enough of the girls, the needles, the foul language and fights.’ She went on to say that Ipswich Borough Council was now taking ‘a zero tolerance approach’ to street prostitution. By July 2007 more CCTV and better lighting had been installed in the red light district.

But by then it was eight months too late.

The discovery of the body of Gemma Adams made the front page of the Ipswich Evening Star, under the headline ‘Somebody’s Daughter’. A shockwave went around the local community, especially in Hintlesham where she was found.

But at this stage it seemed like an isolated event. A woman had been murdered, a prostitute. There probably would have been greater fear if the woman had not been a prostitute. Some people see working girls as putting themselves in the path of danger on a daily basis. The same had been seen in the hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper, Peter Sutcliffe, more than twenty-five years earlier. Sutcliffe had brutally murdered thirteen women and attacked seven others, most of them prostitutes. There had been real terror on city streets in Yorkshire at the time. But this fear had escalated as soon as he killed his first non-prostitute victim.

However, the people of Ipswich were taken aback by the sheer callous inhumanity of how Gemma was found, discarded like a shop dummy from last season. It was a talking point in local shops, offices and at bus stops. The anguish of the Adams family touched many hearts. There was also some moralising and smug self-assurance. Other prostitutes were realising that it was probably bad luck that had singled out Gemma. It could have been them.

As well as establishing ‘no definitive cause of death’, the post-mortem examination on Gemma was able to conclude that there had been no sexual assault. The fact that the body had been found naked pointed to a sexual murder, but Suffolk Police were now having to consider different options. There were also many questions to be answered. Did the killer have consensual sex with Gemma as a business transaction before killing her? What was the motive? Was she left in the brook immediately after death? Was there a connection to a regular punter?

Detective Chief Inspector David Skevington of Suffolk Police made the routine appeal for information in a murder inquiry. He said: ‘Further enquiries need to be carried out to ascertain how long Gemma had been in the water, but our appeals are to anyone who had been in the area of Thorpes Hill in Hintlesham in the past two-and-a-half weeks since Gemma went missing on November 14.’

It was also stated that as she had been found unclothed it was a ‘matter of urgency’ that they find her clothing. The clothes worn by Gemma on the night of her disappearance were as follows: a black waterproof waist-length jacket with a hood and a zip at the front, light blue jeans with studs on the pockets, a red top and white and chrome Nike trainers. Gemma had been carrying a black handbag, but this had been found close to the crime scene. The contents of the handbag were a toothbrush, a tube of toothpaste and a change of knickers.

Posters went up with Gemma’s photograph and description. On 5 December the police made a further appeal for information from the public and urged Gemma’s clients to make contact with them. Regular clients needed to be eliminated from the inquiry, but of course this was a very sensitive matter for the men concerned. Other prostitutes from the red light district were also questioned, many of whom knew Gemma. The police knew that the smallest, most trivial piece of information might lead to the killer.

Searches were also made of the red light district itself, within a specified radius from where Gemma was last seen. Door-to-door enquiries of the local area were carried out in case any local residents had seen or heard something and not yet come forward. The white and chrome Nike trainers that Gemma had been wearing were found near a tyre-fitting firm about a mile (1.6km) from the red light district. But there was no sign of her other clothes.

There was no breakthrough clue, no piece of information giving the police a name or an address. But there were leads and these had to be followed up.

On Saturday 5 December the national press began to take notice. The reason was a chilling one – there were concerns for another young Ipswich woman working as a prostitute. There was a very small report in the Sun newspaper about police fears for missing Tania Nicol, aged nineteen.

Tania had worked the same streets of the Ipswich red light district as Gemma. Police were quoted as saying that there were ‘obvious similarities’ between Gemma’s murder and Tania’s disappearance. Tania Nicol had gone missing on Monday 30 October. That was five weeks ago and more than two weeks before Gemma had disappeared. Where could she be?

Tania had last been seen on that Monday night at 11.02pm. She had been recorded on CCTV outside Sainsburys supermarket in London Road, Ipswich at that time. This is in the red light district. Before that, she had last been seen leaving home at 10.30pm to work the streets. Tania had been reported missing by her mother on Wednesday 1 November.

Police, family and friends had been trying to find her since then, but the discovery of Gemma’s body had made tracing her far more urgent. The fact that both Gemma and Tania were working as prostitutes in the same area, perhaps sometimes sharing the same clients, did not make the police feel optimistic. Five weeks is a long time to be missing when there is no apparent reason.

It soon became clear that Gemma and Tania had been friends. This was not so surprising, as they must have seen each other regularly. Detective Superintendent Andrew Henwood of Suffolk Police said: ‘We are still treating Tania’s disappearance as a separate inquiry, but we have grave concerns for her.’

Sadly those concerns would soon prove to be well placed.