Читать книгу The Wallcreeper - Nell Zink - Страница 6

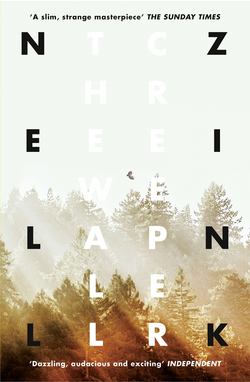

The Wallcreeper

ОглавлениеI was looking at the map when Stephen swerved, hit the rock, and occasioned the miscarriage. Immediately obvious was my sticky forehead. Maybe I was unconscious for a couple of seconds, I don’t know. Eventually I saw Stephen poking around the front of the car and said, “Jesus, what was that.”

He leaned in at the window and said, “Hey, you’re bleeding. Hold on a second.” He crossed behind the car, looked both ways, and retrieved the bird from the opposite ditch.

I opened the door and put my feet outside, threw up, and lay down, not in the vomit but near it. The fir tops next to me had their roots at the bottom of a cliff.

“Can I use this bread bag?” Stephen asked. “Tiff? Tiff?” He kneeled next to me. “That was stupid of me. I shouldn’t touch you after handling this bird. Can you hear me? Tiff?”

He helped me into the back seat and I lay down on the bread. He said head wounds always bleed like that. I said he should have kept quiet. I lost the ability to see and began to hyperventilate a bit. The car pulled back on to the road. From the passenger seat the wallcreeper said, “Twee.”

“Open the bag!” I cried.

“Twee!” it said again.

Stephen pulled over and busied himself with it for a moment. He said, “I thought it was dead. I just wanted to get it off the road. I was going to have it prepared or something, I don’t know. You should see its wings. For me it’s a lifer. It’s like the most wonderful bird. But it’s a species of least concern and actually they’re all over the place except anyplace you would normally go. I identified it even before I hit it. Tichodroma muraria! It was unmistakable, just like they said it would be. So this is great. Dead is not a tick as far as I’m concerned. I identified it before I hit it anyway. It really is unmistakable. You should see it, Tiff. I’m rambling on like this because you might have a concussion and you’re not supposed to sleep.”

“Put on music.”

The wallcreeper protested. “Twee!”

I stayed awake by retching, and Stephen drove defensively but swiftly back to Interlaken.

When I awoke—I mean the next time I was allowed a cup of coffee—Stephen steadied my hand on the mug and said, “I have a surprise for you. But it’s in the kitchen.”

“I don’t think I can get up.”

“Well, it can’t come in here.”

“It will have to wait.” I slurped and he winced. I drank more quietly.

“Twee,” said the wallcreeper.

“You didn’t!” I laughed. But my—what am I going to call it? My down there plays a minor role in several scenes to come. It appeared to be connected to the underside of my stomach with shock cords stretched too tight. I rolled over on my side and coughed. I wasn’t pregnant, I noticed. I clenched my hands into claws and cried like a drift log in heavy surf. Stephen put his hands on my ears. Much later he told me he thought if I couldn’t hear myself I might stop. He said it reminded him of feedback mounting in an amplifier.

Our first meeting prevented a crime. He saw me standing in front of the open gate of the vault. I had an armful of files, my hips were thrust forward, one wee foot in ballet slippers was rubbing the instep of the other, my skirt was knee-length and plaid and my blouse was white and roomy, and I was thinking: If I move fast, I can grab the files on that stuff they use to euthanize psychotics and be down the stairwell in ten seconds. I was a typist at a pharmaceutical company in Philadelphia. The vault was where the bodies were buried, and there was no one in sight. Except Stephen, who walked up and asked my name.

“Tiffany,” he said. “That means a divine revelation. From theophany.”

“It means a lampshade,” I said. “It’s a way to get around the problem of putting your light under a bushel. The light and the bushel are one.”

He didn’t back away. It was one of those moments where you think: We will definitely fuck. It might take a while, though, because Stephen looked as respectable as I did.

He was interviewing for a position in R&D in Berne.

He pretended I was going to be this really difficult and challenging conquest. He wooed me with everything I ever mentioned favorably: Little Debbie marshmallow pies, nasturtiums, the sweet wines so dear to the palate of our shared idol Richard Nixon (a joke), Alban Berg (a joke he didn’t get). He had no intention of going to Berne alone.

My parents were unanimous. “He’s a keeper,” they said. They just about kicked me into bed with him. So the first time we had sex was on their pullout sofa. He was beautiful. It was hypnotic. I was sold.

He warned me that his parents were arty. His father sat me down on the dock behind their house and advised me to enter into a suicide pact effective on Stephen’s fiftieth birthday. I said, “If I make it that long,” which was the right answer. His mother didn’t make it home that weekend. We were married in Orphans’ Court. From the vault to the altar took three weeks. We didn’t talk much about what we were doing. We had a deal.

I hadn’t wanted to be pregnant. It was just one of those things that happen when newlyweds get drunk. It seemed like something I’d get used to. Losing the baby was more dire than I had dreamed possible. Cause and effect had no relation at all. The effect was way over my head, and beside it, and beyond it. It was a bodily distress. I had no way of putting it into words. So I didn’t. Stephen would sit there on the edge of the bed, looking at me, holding my hand, then lie down and tuck himself in. I didn’t feel gloomy. I didn’t even feel sorry for myself. I didn’t tell myself what had happened. If I tell myself stories, I get very sentimental very fast. So I didn’t. I moved around slowly, looking at things before I touched them to make sure there was nothing frightening about them. I had no thoughts to speak of. I wanted to be addressed in hushed tones of pity, even by myself. I wanted to hear my own whispers in the next room and know that I was thinking of me.

We didn’t have friends yet in Berne really, but his colleague Omar came to look at the wallcreeper. Omar was in Animal Health, so he knew something about birds. Also, he was in pharmaceuticals, so he knew how to keep a secret. He told Stephen the bird would never fly again and that stealing it out of the wild was not of the brainiest.

The next day, I got up and went into the kitchen. The wallcreeper flew across the room, banged into the window, and lay still. Then, as before, it sat up and said, “Twee.” It leapt on to its feet like a little karate black belt recovering from a fall. It flicked its wings and tongued a flax seed on the floor.

“I’m worried about it,” I said to Stephen on the phone. “It can’t get any traction on the wall. It needs pegboard. Then we could feed it. We could, like, put bugs in the holes in the pegboard. I don’t like that you’re feeding it bacon or whatever this is on the bulletin board. What is this? It’s going to pull out the pushpins and get hurt. We have to give it bugs, to prepare it for release into the wild.”

“If it gets out, we’ll never see it again,” Stephen said. “Why don’t you go out shopping and buy some curtains? Get white. That would keep it from trying to fly out the window. It’s going to get conspicuous if it starts flying around.” Which was true. It flew like a giant butterfly, or a tiny bird of paradise, or a nylon propeller fluttering from a kite.

“Scramble it some eggs,” Stephen added. “Whatever’s in eggs must be in birds. Relax until I get home.”

After Stephen saw the curtains and screwed the pegboard to the wall, he wanted to have sex standing up in the kitchen. It had been three weeks.

We kissed, but my whatever had not healed. It was hot and dry. (I mean my brain.) I just stood there in a state of mournful passivity while he knelt down and licked me, touching my asshole rhythmically with one finger and petting my thigh in counterpoint. I felt sad. His awkward hands reminded me of the flames around Joan of Arc at the stake. But I knew after we started to have actual sex I would feel better. However, that was before he entered my butt with the rest of his hand followed by his penis and the metaphoric auto-da-fé became a thick one-to-one description of taking a dump.

Now, all my life I had fantasized about being used sexually in every way I could think of on the spur of the respective moment. How naïve I was, I said to myself. In actuality this was like using a bedpan on the kitchen counter. I knew with certainty that “pain” is a euphemism even more namby-pamby than “defilement.” Look at Stephen! He thinks he’s having sex! Smell his hand! It’s touching my hair! I thought, Tiff my friend, we shall modify a curling iron and burn this out of your brain. But I didn’t say anything. I acted like in those teen feminist poems where it’s date rape if he doesn’t read you the Antioch College rules chapter and verse while you’re glumly failing to see rainbows. I was still struggling to dissociate myself into an out-of-body experience when Stephen came, crying out like a dinosaur.

I gasped for air, dreading the moment when he would pull out, and thought, Girls are lame.

After a shower with fantasies of pharmaceutical-grade trisodium phosphate and nothing to wash with but gentle pH-negative shower gels, I had recovered sufficiently … actually I had recovered from everything! I was no longer in love! My sense of depending on Stephen for my happiness had evaporated. Furthermore, I had overcome my fear of intimacy. All intimacy was gone. I didn’t care whether Stephen ever understood me. I knew it for a fact. I had just proved it.

In addition, I felt almost nostalgic toward socially acceptable horrors with larger meanings related to reproduction. (As I was to learn, reproductive urges will serve as an alibi for just about anything.) I recalled things I had seen in the hospital that did not admit of euphemism—certain stark natural occurrences that gave the lie to language itself simply because no one, anywhere, absolutely no one in the world, would ever take a notion to claim they were fun. Irredeemable moments with no exchange value whatsoever.

I went to bed and lay propped up on pillows, thinking about it. Stephen came out of the shower and stood naked in the doorway. He was beaming like a god, radiant with abashed joy. “Was I bad?” he asked.

“You were super-bad,” I said. He knelt across my chest and eventually sort of fucked my mouth. He was uninhibited, as in inconsiderate. I felt like the Empress Theodora. Can I get more orifices? I thought. Is that what she meant in the Historia Arcana—not that three isn’t enough, but that the three on offer aren’t enough to sustain a marriage?

Omar and his wife had us over to dinner. She served unaccustomed delicious food and had us sit on unfamiliar comfortable furniture. She wanted to know about the wallcreeper.

“It’s beautiful,” Stephen said. “I mean, not flashy like ducks or elegant like avocets—”

“Flashy ducks?” Omar objected. He was from Asia.

“There are plenty of flashy ducks here,” I said in Stephen’s defense. “Relatively speaking.”

Stephen said, “Okay, what I mean is, it has this essential duality. It’s tiny and gray and you’d never notice it, and then these wings. Woo. You have to see them.” He spread his hands like outfielders’ mitts and shook them to express his incapacity to understand the wallcreeper. The gesture was like a prayer of desperation, but he never raised his eyes, as if to say, there is no one to appeal to for help, not even me.

It was an effective gesture. Omar’s wife leaned back, nodding, believing in the wallcreeper.

Stephen came home one day mad at Omar, who had told him which zoo collects wallcreepers. Omar opined that we would be given amnesty if we surrendered Rudolf voluntarily. He reemphasized that in Asia even the squirrels are flashy and piebald, and no one should get attached to a wild animal for its looks. Omar’s job involved feeding caged beagles different chow formulas to see which ones lived longest. The lab record was fourteen years.

Otherwise Stephen was never mad at coworkers. He got along beautifully with his bosses and subordinates. Everyone liked him. They liked his work on the new stent. They admired his pretty wife with the orthodox-Jewish-looking outfits, but hey, not her fault Americans are dowdy. They frowned at her pregnancy no sooner announced than cancelled. One thing he never told them about: birds. The company employed expert tax-evasion consultants, semi-closeted gray-market OTC pirates, hail-fellow-well-met good old boy executives who laughed off multi-million-dollar fines for taking risks that killed people, PR hacks who wrote threatening letters to Nelson Mandela about socialized medicine. They practiced twenty-seven kinds of window-dressing and I had typed letters about them all. But even the veterinarian in regulatory affairs whose life was spent tweaking a children’s book about cats that sing opera was less secretive than Stephen. No one at the company knew Stephen birded, not even Omar’s wife. I only learned the truth when he pressed my wedding present into my hand: two-thousand-dollar binoculars.

What were we doing back of Interlaken that day, anyway? Stephen with a fishing hat, binoculars, camera equipment, a scope and a tripod on his back, me with a fishing hat, binoculars and a stadium kit, stalking around like thieves casing an entire landscape. Driving a huffing VW diesel up higher than you’re allowed to go, driving through gates and across cattle guards to a private “alp” because birds like cars and hate people. Then back down with a whinchat, a shrike, two hawks and a chough, not much of a haul until we hit the species of least concern.

In December there was a cold snap, and Stephen came home in a state. “There’s an evasion,” he said. “We need to go north.” All sorts of birds from far, far away that wintered in places like Denmark had decided even Holland was too cold, and were heading south in dribs and drabs, fetching up in swirling eddies near Zurich after they caught sight of the Alps.

“Oh, you go,” I said. “I’m reading a book some guy raved about in the Times called The Man Who Loved Children.”

“Sweetie,” he said. He sat down next to me and put his arm around my shoulder. “I’m so sorry.”

“No, no!” I said. “It’s not like you’re thinking. He has seven kids and he hates them. He’s going to save the world with eugenics and euthanasia. I could go with you. But are you really sure I need to spend the weekend stumbling around on frozen dirt clods helping you level your tripod?”

“We could try again instead,” he said. “Sex party weekend.”

“I’m still kind of all tore up,” I said. “You go.”

“Twee,” the wallcreeper remarked. “Twee!”

“Is it his suppertime?” I asked.

“It’s only going to get worse,” Stephen said. “Do you know what’s happening to his gonads?”

“No.”

“As his chin turns black, his testes are swelling from the size of pinheads to the looming, ponderous bulk of coffee beans.”

“Wow,” I said.

He kissed me. “His tiny heart is throbbing with love for someone he’s never seen. I love you, too, you know.” He embraced me, squeezing me very tight. “I love you so much, Tiffany.” The wallcreeper protested. “Cool your jets, Rudolf,” Stephen said.

He had named our bird after Rudolf Hess because its colors were those of a Nazi flag, with black on its chin for the SS in spring. To imply a certain tolerance for at least the form of his joke while rejecting its content, I had to suggest we name it after an anarcho-communist and came up, off the top of my head, with Buenaventura Durruti. But Rudolf stuck. So its name was Rudolf Durruti.

Sometimes I would sit and go over things Stephen had said during our whirlwind courtship, fitting them into a context I was learning only slowly. It was hard. He had told me so little about himself, intent on taking note of my little foibles so he could, for instance, surprise me with tickets to Berg’s Lulu.

The birds were Stephen’s intimate sphere. He didn’t have to be cool or funny or even appetizing about them. “Breeding and feeding,” Stephen called their lifestyle, making them sound like sex-obsessed gluttons (that is, human beings) instead of the light-as-air seasonal orgiasts they were in reality—ludicrously tragic animals, always fleeing the slightest hint of bad weather in a panic, yelling for months on end to defend territories the size of a handball court, having brief, nerdy sex and laying clutch after clutch of eggs for predators, taking helpless wrong turns that led them to freeze to death, drown, starve, or be cornered by hunters on frozen lakes, too tired to move.

To Stephen they were paragons of insatiable, elemental appetite. I saw them differently. I imagined two ducks, loyal partners. When the hunters cornered them, would they turn to face them, holding hands? Hell no. They would scatter like flies in as many directions as there were ducks. The duck who got hit would look up with his last strength to make eye contact with his lifelong friend, who would shake her head as if to say, “Hush now. Don’t rat me out just because you’re dying.” Love would conquer all.

When my parents and my sister came for Christmas, I finally got out to see the old city. I took my parents to a craft market so Stephen could sleep with my sister. She worked as a bikini barista in greater Seattle and liked a good time. But he didn’t sleep with her. She became irritable. She came into our bedroom with only panties on, asking to borrow my bathrobe. Stephen looked up for about a quarter of a second.

Berne was beautiful. It had colonnades like Bologna and boutiques like New York. On three sides of its grid, it fell away to a wild river in a gorge. The river enfolded the city like a uterine wall. Across the bridge bears stalked back and forth on the banks. It was too small to move through. All you could do was change positions in place. From the top of the church tower you could see all of it. Every speck. I went with my sister to cafés. She said she would marry Steve in a minute, but in Berne her eyes caressed everything and everyone. Everything in Berne had a delicious texture advertising a rich interior. Nothing was façade. It was clean all the way down forever and forever, like the earth in Whitman’s “This Compost.” I told Stephen I wanted to live there. He claimed in the old city you couldn’t have a washing machine because the plumbing was medieval.

Our apartment was fifteen minutes from downtown Berne. Our trolley stop was next to a gas station, which is where Elvis the Montenegrin worked behind the counter, selling beer and candy. His shift ended around the time Stephen went to work. I bought the International Herald Tribune every day.

Pretty soon Elvis knew I spoke English. Soon after that he knew what baked goods I liked and how I liked my coffee. He knew how to smile charmingly and ask for sex by name. The first time I invited Elvis to our apartment, I realized that even the hottest hot sex with Stephen had been all in my head. I had hypnotized myself because Stephen had a job that could support us both and secretarial work bored me. I saw that I had followed the chief guiding principle of the petty bourgeoisie in modernity and made a virtue of necessity in telling myself my husband was a good lover. Elvis raised my consciousness. But there are reasons they call it necessity, so I decided Stephen’s stability was good for me. Elvis was flighty. He had tight pants and a degree in superannuated theory from Ljubljana. He was always broke a week before payday. “I take what I want,” he liked to say. He was hopelessly in love with his own thoughts, watching them like a show on TV, zapping through the channels. But he trusted his eyes, which was nice. He would absent-mindedly taste my sweat, or try the weight and flexibility of my hair, comparing it to heavy gold as if he had pulled off the heist of the century. My eyes struck him as particularly expensive. Objectifying my body saved him from objectifying my mind. He moved gracefully through and around me like a wave. My thoughts were my business. I thought, Elvis is a good lover.

Stephen unexpectedly announced that he had been to a music shop and acquired two telephone numbers. “I’m an operator,” he explained. Even his taste in music was news to me. When I met him, his things were already in storage, and by the time the container with his vinyl collection arrived from Rotterdam, I was in the hospital. “Why, why, why do the wicked ones rule,” he sang suddenly. He joined a sound system where everyone was younger than he was. I thought maybe something about his narrow escape from fatherhood had inspired him to become younger. He grew his hair an extra half-inch and started drinking energy drinks. He used headphones because his music might upset Rudolf, who was molting. I never had to go to their shows. Stephen said he needed his space, because we were going to be together for sixty-plus years.

So his knob-twiddling was the first thing I found out about Stephen other than myself and birds. The birds were secret from his coworkers, but they were all I got.

In March, Rudolf became very restless. He would climb his pegboards up to the crown molding, let go and drop to the floor, then flutter from room to room like an autumn leaf tied to a string. He stopped saying twee-twee-twee and started cheeping like a sparrow and crying out in delirium like a skylark. Stephen said Rudolf wanted to find a nesting site and sing himself a girlfriend. He definitely seemed very driven. One Sunday morning at dawn (we were going to Lake Biel) we opened the kitchen window for him. Rudolf flew out, then back. He clung to the stucco outside and looked at me. Stephen said, “Go on, Rudolf. This is Switzerland. You’re safe!” Rudolf climbed straight up in short bursts of fluttering and was borne away on the wind. Stephen told me we should try again to have a baby, right now.

“What about zero population growth?” I objected.

“My mother and father were only children,” he said. “That means I’m entitled to four to replace my grandparents.”

“What about global warming?”

“If it weren’t for global warming, we’d be under an ice sheet a mile thick right now.” He gestured toward the mountains. “But look at us. Earth as far as the eye can see. I love global warming! And I love you!”

Something about the implied comparison made me nervous. I was pretty bad as wives go. Where Stephen was concerned possibly epoch-rending, world-destroying bad. But without me he’d be under an ice sheet, so maybe I was doing him a favor.

It was plausible. It was also not enough. I said I wasn’t ready. But I had sex with him, feeling like a very dutiful wife.

Soon after that I went out to dinner downtown with Elvis. It was the day after payday. He talked nonsense and made me laugh. We walked the colonnades and fetched up against the ramparts, facing in. You couldn’t look across the river. There was nothing there. Berne lived turned inward on itself. But it wasn’t self-sufficient; it was more like a tumor with blood vessels to supply everything it needed: capital, expats, immigrants, stone, cement, paper, ink, clay, paint. No, not a tumor. A flower with roots stretching to the horizon, sucking in nutrients, but not just a single flower: a bed of mixed perennials. A flower meadow where butterflies could lay eggs and die in peace, knowing their caterpillars would not be ground to pulp by the mowers. Continuity of an aesthetic that had become an aesthetic of continuity. That was Berne. I leaned against the city wall and Elvis kissed me, closing his eyes so as not to see the bears. It was dark and freezing cold.

Birding in winter involves a lot of long car rides. (I saw Elvis a lot, so I didn’t mind spending time with Stephen on weekends.) One morning I got around to begging Stephen to tell me about himself. He turned out to be much better at talking when he was driving the car. The landmarks steadily passing by the side of the road functioned as encouraging responses, telling him to go on. The distractions filled all the little gaps with what seemed like conjunctions linking dependent clauses. “You know, there’s not much to say,” he said. “I mean, I’m going to have to drop out of this sound system because they want to go on tour. I’m trying to think when I started playing drums. I guess maybe sixth grade. My parents got me lessons. I had a trap set in the basement. A red Tama drum kit. Getting lessons helps. Guys play for ten years and can’t even do a snare roll if they never got lessons. My first band was Gold Purple Scarlet. We played this monumental Lovecraftian dark epic schlock,” he smiled, borne away like a boat against the current, “and we looked like hobbit vampires. I had long hair and I was so into drugs. Prescription painkillers. Our lyrics were like ‘Fear the vengeance of the blood dwarf, the moonlit trumpets ride,’ shit like that. It was white supremacist, among other things. I mean, you don’t know when you’re a kid railing against hip-hop and the backbeat whose hands you’re playing into. Whose freak flag, you know. My parents were in hell. Plus I was addicted to Darvon and sometimes codeine. But we had such a great time. It was like nothing existed outside of the band. We brought out an EP and two CDs, and then we broke up because Lydia, she was the singer, her parents got her put in the hospital, and when she got out, she was gone. She went up to Maine, like as far away as she could possibly get. She was walking silly walks from all the Prolixin. That’s when I decided to go to med school and be a psychiatrist. But I had this problem of shitty grades and mediocre scores, so I went to that work-study program at Temple instead. I know devices are cool and everything like that, but I wish I’d had the patience for chemistry. I was so fucking lazy. I could be working on cancer or HIV, and here I am making parts for alcoholic smokers. So it’s good I’m still doing music. And I have the cutest wife. Hardcore was never my thing when I was coming up. I was basically into anything where you wear black, the whole range from EBM to minimal techno. I was a lonely kid. My mom was such a weirdo, like a scarlet macaw. She was always wearing scarves and big pants, like ‘flowing garments.’ Did I ever tell you she slept with Paul from Peter, Paul and Mary? I would basically listen to absolutely anything where you got to wear black.” He paused to make a left turn. “I kind of liked dub, you know, Lee Perry and Mad Professor and even goofy shit like Judge Dread, and I was really into Bootsy, plus like sludge and death metal, so that whole tight-ass rude-boy mod thing was not my idea of good. I liked psychedelics, but there was nowhere to get them. I was I guess eighteen when I did rehab. My dad was so mad at me. I thought he was going to kill me. I seriously thought he was taking me down to the clinic because he no longer trusted himself not to kill my ass. But my parents were pretty sweet to me most of the time. So anyway, it was when I got older and kind of settled down that I started getting into these heinous happy party sounds. You can’t be into downers and listen to dubstep. It’s not doable.”

“Wait, how did you get into birds?”

“Oh, that was basically my scout leader. He also coached track, so we saw each other all the time. He had a house on the Chickahominy next to a marsh. It was brackish water, smelled totally anaerobic, but it got a lot of crabs. That was like paradise. We used to go crabbing all day. We’d go fishing in the morning in the pond back of the cove, fry bluegills and bass for lunch, tie up their heads on some string and go out and stand in the river barefoot, pulling in blue crabs. Then we’d build a fire and get this great big pot and some Old Bay and put a hurting on those crabs. I didn’t much get into birds until I was at least, I don’t know, sixteen? I wasn’t a kid anymore. It was when the other kids were getting into hunting, I guess, and I knew that was not for me. He was my math teacher, too, so he used to tell me about the special theory of relativity and everything like that. He liked clamming a lot, but I really hated clams. So my eagle scout project was to study the ospreys that were breeding and feeding in the cove.”

“I thought you were addicted to codeine.”

“Listen, man, I went to state running the mile. There are a lot of hours in the day when you’re a kid.”

I had to admit the truth of that statement. I replied, “The most ambitious thing I did at that age was let these girls pierce my ears.”

“I would have done anything in the world I thought would piss my parents off,” Stephen said. “Eagle scout was a conscious trade-off to keep my dad from killing me.”

I realized that he was not like me at all. I only did things I felt strongly moved to do. As a child I consistently felt I had no options and was surprised by my parents’ strong reactions to the entirely inevitable things I did. My life moved forward in ineluctable leaps. The only smart leap I had ever made, in their opinions, was marrying Stephen. It was what set me apart from my sister, since secretary and bikini barista are not really such different professions when you get right down to it. I mean, I’ve served plenty of coffee in my day.

“Were you in a band at Temple?” I asked.

“No. Once I moved out of my parents’ house, I calmed down a lot. I just didn’t like having people breathing down my neck.”

That made sense. It would be a reason to marry someone too shy to ask personal questions. It was also a way of saying: I wasn’t doing drugs when you met me and I’m not doing drugs now, but if you breathe down my neck, I’ll do drugs.

“Isn’t it hard,” I asked, “getting up so early in the morning on weekends after you worked all week? I mean, it’s hard for me, and I’m just writing a screenplay.” (I had intimated that I was a writer with industry connections so he wouldn’t make me work.)

“Oh, I feel great,” he said. “It’s great getting out of the lab. I feel exhilarated. I feel like I can concentrate for hours. I feel on top of the world right now. This is a really good time for me.” He reached out and clamped his hand lovingly on my leg. He was shaking.

When we got to the river, I helped him set up his blind. It was a bit cramped, so first he would get in, and then I would hand him everything he needed before going back to the car to read.

He saw a greenshank, linnets, and a poacher. He made me look at the guy. We took a picture through his spotting scope, but it didn’t turn out.

It was soon after that that I started saying, if he asked me what I was doing, “Oh, breeding and feeding.” The majestic simplicity. It always made him laugh. But I couldn’t envy the birds. Their lives weren’t as simple as mine. My life was like falling off a log comfortably located somewhere light years above the earth.

At Elvis’s suggestion I took a course in Berndeutsch. I learned ten verbs for work: work hard (drylige, bugle, chrampfe, schaffe, wärche), get stuck with jobs no one else wants to do (chrüpple), work slowly (chnorze), work carelessly (fuuschte), work absent-mindedly (lauere). Stay at home and putter around doing little harmless chores (chlütterle). I learned fast and the teacher said maybe it was an advantage my not knowing any German. Then the ten weeks of the course were over and I didn’t know anything anymore, except that I would never look for a job. When people other than Stephen asked me what I did, I could say, “Chlütterle.” Another laugh line.

Elvis said he wanted to go dancing, which would involve staying out very late. Going dancing was his reason for being, and he wanted to share it with me. I wasn’t sure I could get that past Stephen, but I agreed to try. Stephen said, “That sounds like a date.”

“It totally is a date. Obviously this guy wants in my pants. But I mean, when’s the last time you went dancing? For me I think it was my sophomore year. And I wouldn’t know where to go. He’s a nice guy. I’m sure you know him. The guy with the beard at the gas station. He’s totally harmless. He’s a disciple of Slavoj Žižek.”

Stephen snapped the International Herald Tribune tight to turn the page. “That is the tiredest line in Christendom,” he said.

“I know. It’s not his fault he’s a tragic figure. It’s never a tragic figure’s fault. That’s what makes them tragic. But he says he knows this really fun place to go dancing, not a disco but, like, a bar where they play all kind of ‘mixed music.’ ”

“Do you need a chaperone?”

“Would you please?” I said. I couldn’t really say no. We picked Elvis up at his place. I had never been there. It was farther out of town, up at the edge of the woods. An old house. He came out as soon as the car pulled up. The street obviously didn’t get much traffic late at night. Elvis directed us to the most pitiful bar I ever saw. Young men unlikely to be in the possession of Swiss passports danced with eyes half-closed, snapping their fingers, while women in various states of disrepair jockeyed into their axes of attention. Lumpy, lantern-jawed, pockmarked, bucktoothed, short, tall, or simply drunken women, here to pick up devil-may-care subaltern gigolos for a night of horror.

I saw Elvis through new eyes. “You are so much beautiful,” he would often say charmingly as he worshipped at the altar of my body. Looking around, I could only think that a bar where I am the best-looking woman by a factor of ten is not a bar where I want to be, and that beauty is apparently relative. I felt both better- and worse-looking than before. Better because I was suddenly reminded that the world is not all college girls and secretaries and trophy wives, and worse because everything in the whole universe is contagious if you look at it long enough. Just opening your eyes puts you in front of a mirror, psychologically speaking. Garbage in, garbage out. Or rather, garbage goes in, but you never get rid of it. It just lies there turning to dust and slowly wafting a thin layer of grime on to every other object in your brain. Scraping the gunk off is not only a major challenge, but the chief burden of human existence. That’s why I keep things so clean. Otherwise I would see little flecks of Rudolf-shit everywhere I looked, from Fragonard to the Duino Elegies.

“I am not staying here,” Stephen said. “Do you want to stay?”

Elvis asked if he knew another place. Our next stop was called Mancuso’s Loft. It was running drum ’n’ bass. The proprietor waved us in. Here I saw Stephen through new eyes. Then I ran to the ladies’ room and stuffed my ears with toilet paper. Stephen led me to the floor and yelled, “I’m going to dance a little bit!” He then proceeded to dance as if he had never seen me, or any other human being, before in his life. Cranes came to mind.

Touching my elbow, Elvis remarked, “This club is so much beautiful,” and headed for the bar. Elvis was right. In Mancuso’s Loft, I felt below average-looking and quite conspicuously ill-dressed. My pants revealed nothing whatever. My shoes were comfy. My shirt had long sleeves so thick I was soon terribly hot.

“I like your husband,” Elvis said. I said that was not really his assigned task. “No, he has something. Un certain je ne sais quoi. You know what I need? A girlfriend. By myself, I am never getting into this place. You think they let me in? A brown man alone, with a beard? Ha!”

“You’re not brown! You’re lily-white anywhere but Denmark!”

“Many times, I am standing in the queue outside clubs like this. And all the time, I think I am living in Berne. But I am not living in Berne. I am living in the Berne that reveals itself to me, okay, a white ‘Yugo’ if you please but with no connections, with nothing. A cashier in the petrol station, with nothing to his account but a few women. Yes, I say it openly. I have nothing to offer this town but my body. My body to strike the keys of the cash register, my body to find other bodies and search for warmth. My body is my capital. You, this beautiful woman, are my social capital. And then I was taking you, you particularly, to this horrible bar. I see now it is so very horrible, this bar.”

“Elvis, calm down,” I said. “You’re a model of successful integration. You even speak Berndeutsch, and you’ve only been here eleven years!”

“Are they speaking Berndeutsch in this club? No, they speak French!” I didn’t know how he had decided on that one, because I could barely hear even him, much less other people. “I speak the language of the gas station! I have shamed myself. I hoped to leverage one woman to meet another. Not to earn a woman with the honest work and the natural beauty of my body! This crazy Swiss language has made me a capitalist of women! And what is my wages? I insult you, the most beautiful woman in Switzerland. This town has made of me a body without a brain. I will leave this place and go to Geneva,” he concluded, taking both my hands.

“Don’t do that,” I said.

“No, I won’t if you don’t permit it!” he cried ecstatically, throwing his arms around me.

Stephen drifted over, bouncing on the tips of his toes, and beckoned to me. “You need ketamine?” he whispered.

“Umm, no?” I said.

“I got three,” he said. “I think I might stay here. You want the car keys? I’ll take a taxi.”

“Don’t give Elvis any drugs.”

“I don’t take drugs,” Elvis volunteered. He had never been in a band, so he could hear much better than we could. Stephen and I were always stage-whispering about people sitting near us in cafés and drawing stares.

“That’s dandy,” I said. I pocketed the keys and took Elvis’s hand. “Let’s blow this joint. That okay with you?”

Stephen mouthed the word, “Arrivederci.”

We arrived at the wind-struck farmhouse where Elvis lived with (judging from angle of the stairs) a herd of chamois and mounted to the third floor hand in hand. After a warm and harmonious session of sixty-nine (Elvis was not too tall) to the sounds of Montenegrin folk rock (East Elysium—my favorite song was “Wings [Who You Are?]”), he said, “I want to buttfuck you.”

“What is it with guys?” I said. “You’re all obsessed.”

“I never mentioned it before!”

“So where did you get the idea? From bad porn with stock footage from the sixties? From daring postmodern novels like Lady Chatterley’s Lover?”

“From doing it.”

“FYI, it’s no fun, so forget it.”

“Just forget it?”

“Forget it.”

Elvis said mournfully, “If you loved me, you wouldn’t care that it’s ‘no fun.’ That’s the difference between our thing and a real love.”

“Wait a second,” I said. “I don’t mean to sound like a crank, but are you saying that what makes our relationship valuable is my willingness to suffer for you? Are you aware that I’ve never suffered for you for even, like, one second? That’s what makes our relationship so optimal, in my opinion.”

“You must have done buttfucking to know that it’s ‘no fun.’ So you suffered for someone else, right?”

“So now you want to move up in the world?”

“I’m in love with you. I want a sign that I mean so much to you.”

“You asked me if I’d move to Geneva with you, and I said no. You accepted that right away.”

“I can’t ask so much of you. That’s too much.”

“Are you aware that if you gave me a choice, like if I actually had two options in life, anal sex and moving to Geneva—”

“You would move to Geneva?” He threw his arms around me again, quivering with spontaneous joy.

“You’re not understanding me,” I said, pushing pillows in the corner so I could sit up. “There’s suffering, and then there’s boring stuff, and then there’s stuff that’s just plain stupid. I’ve done my share of suffering for Stephen. And other guys. Like crucifixion, I mean that level of suffering. Like St. Laurence. ‘Turn me over! I’m done on this side!’ I don’t see what that has to do with having a good relationship. It should be about getting through difficult stuff together. Difficult stuff the world throws at you, not difficult stuff you do to each other. The difference right now between me and St. Laurence is, he didn’t have the option of taking his hand off the hot stove.”

“You are fierce,” he replied, pulling the blanket up around his naked body to hide it. “I am never asking another woman for buttfucking.”

“Are you bisexual?”

He frowned. “I am polymorphous pervert! Where I find love!”

I shifted back into neutral and once again accepted the need for negative capability in this world. We had loving, beautiful sex just as soon as we could get ourselves to stop talking—loving and beautiful in the expressionist, pathetic-fallacy sense in which you might say a meadow was loving and beautiful even if it was full of hamsters ready to kill each other on sight, but only when they’re awake. I mean, you just ignore the hamsters and look at the big picture.

The next day, around six p.m. after he woke up, Stephen said, “Let’s make a baby.”

“I feel like Saint Laurence on the gridiron,” I said.

“No, you’re mixed up. Miscarriage is nothing compared to childbirth. You got off easy. You’re like Saint Laurence saying he doesn’t want to go to Italy in July. I’m asking you right now to risk your life and health for my reproductive success. I feed, you breed. Come on!”

“Sounds tempting,” I said. “If I could lay eggs and you agreed to sit on them, I might even do it.”

“Can we fake it?” he said. “Are you fertile?”

“Not exactly.”

“Then meet the father of your triplets!”

“You’re totally insane,” I said approvingly. Stephen was actually sort of interesting when his mind opened the iron gates a crack and let the light out.

“The central ruling principle of my life,” Stephen explained in a grandfatherly way, “is ‘Let’s Not And Say We Did.’ Most people don’t give a fuck what you’ve done and not done. If I put a picture of you and a baby on my desk, I can get promoted. All anybody wants to know is little sketchy bits of information, strictly censored, and that’s enough. It’s more than enough. Did you ever sit down and actually make a list of what you know about, like, Togo? ‘Is in Africa.’ That would be the grand total of your knowledge. But when people say the word ‘Togo’ you let it pass, the same way you let hundreds of people pass you on the street and in the halls every day. And every one of them is as big as Togo, inside.”

“That’s pure bathos, and I know nothing about Togo,” I said. “But somebody like, say, Omar’s wife, I don’t know her either, but what with my life wisdom and mirror neurons and all that, I figure I have a pretty good sense of what she’s about. But only because I’ve met her. I mean, if I said, ‘Togo is charming,’ you’d get the idea that you liked it until further notice, but if then I said, ‘Togo brags about doing those impossible word puzzle things in the Atlantic and dropping out of Harvard med to get a doctorate in nutrition,’ you’d think, who is it trying to impress? But you haven’t even begun to talk about its secret sorrows or whatever.”

“You can bet your buttons Togo has secret sorrows,” Stephen said. “If anybody knew what they were, the world would be filled with raw, bowel-torn howling. That’s Stanislaw Lem. I was going to say, I didn’t love you when I married you. It was like, ‘Let’s Not And Say We Did.’ But now I feel like Apu in The World of Apu, except instead of being faithful to me and dying in childbirth like you’re supposed to, you’re fucking this Arab guy. So tell me, Tiff, what is going on?”

“He’s Montenegrin!”

“Montenegrin my ass! He’s Syrian if he’s a day! ‘Elvis’! It’s like a Filipino telemarketer calling himself Aragorn!”

I pouted.

“Ever try to make a list of everything you know about Elvis?”

“What would be the point? I was just trying to have some exciting sex.”

“Could you not try?”

I was silent.

“Could you love me a little?”

“Actually I do love you. Elvis told me. It’s breaking his heart.”

On Monday morning I bought the International Herald Tribune and some milk and said, “Elvis, I need to talk to you.” For the first time I noticed that he was reading Hürriyet. Over coffee at my place, he explained that his family had left Montenegro some generations before. But their women preserved the legendary beauty and kindness of the people of Montenegro, once immortalized so memorably by Cervantes in his lady of Ulcinj (D’ulcinea), and their men weren’t bad either. He showed me his Turkish passport. His name really was Elvis.

“Tiffany, my love,” he said. “What does it matter where I am from? You are an American! You know better than any shit European that we are all equal children of God!”

The next Saturday we went birding to an ugly artificial lake and Stephen asked me to talk about myself. “Let’s see,” I said, “being little sucked, but it had its advantages. Sledding is a lot more exciting before you turn ten. Of course I couldn’t really swim until I was eleven.”

“And then?”

“Well, my parents weren’t real particular about their choice of a boarding school, so I went to basically a home for wayward girls. I didn’t learn a whole lot. Like, our chemistry teacher was the choir director’s wife. I used to play around in the lab on weekends. I used to dump all the mercury on the counter and play with it.”

“Yeah?”

“I was supposed to go to Bryn Mawr after my junior year, but it was too much money, so I took a scholarship to Agnes Scott.”

He shuddered appreciatively.

“Then I moved to Philly and got a job, and then I met you.”

“Short life.”

“Well, life is short.”

“My child bride.”

“Hey, it’s not that bad! I had a thing with the riding coach at school, and in Philly I OD’d on heroin and they called me crusty mattress-back!”

“What?”

“I’m kidding. That was somebody else. This girl name of, um, Cindy—”

“You just made her up.”

“Okay, her name was Candy. I’m serious. Candy Hart. It sounds like a transvestite from Andy Warhol’s factory, so probably she made it up. She said she was from Blue Bell, so probably she was from Lancaster, and she said she was fourteen, so probably she was seventeen. I’ve never met anybody I can be entirely sure I’ve actually met.”

We saw bearded reedlings and a ruff. We would have seen more, but there were dog walkers there scaring everything off.

We went on a birding vacation to the lagoons of Bardawil. All the men I saw there reminded me of Elvis.

When I got back I demanded answers. He cradled his coffee in his hands and said, “Now I am telling you the truth. I am a Syrian Jew. My grandfather converted to Catholicism in 1948, but he took a Druze name by mistake and was not trusted by the Forces Libanaises, so then—”

“Just shut up,” I said. “I think you’re cute. That’s your nationality. Cute.”

On the phone my sister said, “Tiff, you have got to get a life. You think I have time to have sex? Guess again! I spend so much money on outfits for work I had to get another job!”

I said to Stephen at dinner that maybe we should try again to have a child. Our marriage had begun in the most daunting way imaginable. We had barely known each other, and then we had those accidents and that jarring disconnect between causes (empty-headed young people liking each other, wallcreepers) and effects (pain, death).

He objected. He said, “I’m sure there are couples that are fated to be together, like they meet each other in kindergarten and date on and off for twenty years, and finally they give up because they realize they’ve gotten so far down their common road that there’s nobody else in the entire universe they can talk to, because they have a private language and everything like that. Do you really think that applies to us? What do we have in common? We don’t even have Rudi anymore.”

“A baby would be something in common.”

“That’s it. Have kids and turn so weird from the stress that nobody else ever understands another word we say. A couple that’s completely wrapped up in each other can get through anything, because they don’t have a choice. Right now we have the option of floating through life without being chained to anybody, but instead we pile on a ton of bricks and go whomp down to the ground.”

“Are we ever going to both want a baby at the same time?”

“I hope not!” Stephen said. “I want to float through life. I like being with you, and I don’t want to be chained to anybody. I mean, when you got pregnant, I could deal, but if you’re not pregnant, I can also deal.”

“That’s a relief. I was afraid if I didn’t have kids soon, you’d make me get a job.”

He paused and looked at me fixedly for a good ten seconds. “I’m starting to catch on to you,” he said. “You were born wasted. You live in a naturally occurring K-hole.”

“I do my best.”

“Here’s the deal. I need your baby for my life list. It’s one of the ten thousand things I need to do before I die, along with climbing Mt. Everest and seeing the pink and white terraces of Rotomahana. The baby is the ultimate mega-tick.”

“Like a moa,” I suggested.

“Exactly. There will never be another one like it, and there was never one like it ever, so actually it’s a moa that arose from spontaneous generation. A quantum moa.”

“Babies are totally quantum,” I said. “That’s why it feels so weird when they die. You feel like it had its whole entire life taken away and all the lights went out at once, like it got raptured out of its first tooth and high school graduation in the same moment.”

We munched on food for a bit.

I said, “Stephen, may I ask you something? When we had anal sex that one time, was that for your life list?”

“Yeah.”

“It wasn’t on my list.”

“I’m sorry. I figured human beings are curious. I try not to avert my eyes when life throws new experiences my way. But I guess nobody ever asked me to stick the pelagics up my ass.”

At nine o’clock on a November morning I looked out the kitchen window and saw three birders on the sidewalk digiscoping me. When I opened the curtain, they moved their hands frantically from side to side at waist level, as if to say, Stop! When I opened the window, they shouted, “Halt! Nicht bewegen!” I stuck my head out and looked around. Rudolf was waiting under the eaves. When he saw me, he let go, dropped two stories, and then fluttered up and in.

Stephen was overjoyed for a day and a night. Then I was on all the birding forums as wallcreeper girl. People were writing embarrassing things. They wrote, “Bernerin ist gut zu Vögeln,” the oldest joke in the book. Bernese woman is nice to birds/Bernese woman is a good fuck. You could call it homonyms or a pun, but actually the only difference is that the birds are capitalized.

Birders are sort of a male version of the women in that bar Elvis took us to. They attract birds by kissing their thumbs until it squeaks. They can’t exactly attract women that way, but why would they want to? Women are ubiquitous, invasive—the same subspecies from the Palearctic to Oceania. Trash birds. However, it should be noted, birders are primates and thus, like birds, respond to visual cues. I had leaned out the window in a loose bathrobe, first drawing my hair to one side around the back of my neck so it wouldn’t get in the way. Everybody likes a woman barefoot in breeding plumage in the kitchen. Stephen said if ornitho.ch had a habit of publishing the locations of wallcreeper sightings we would be in deep shit, and also that I should get a modeling contract for optics like Pamela Anderson for Labatt’s.

Whenever I looked at the video online, I saw Elvis standing faintly illuminated in the deep shadow of the kitchen. But Stephen only had eyes for Rudolf and his floppy rag-doll trajectory up his spiral staircase of air into my arms. Stephen really did love birds. Plus psychedelic drugs, discretion, and sarcasm. The beard kept Elvis from having a face-shaped face. His dark body hair broke up the outline of his naked torso like camouflage on a warship.

As I screwed Rudolf’s bacon into his pegboards with my thumb I felt glad we were too poor to live downtown. Rudolf would never have found us. Would he?

Rudolf sang, “Toodle-oodle-oo!”

Stephen and I loved nature more than ever after we’d decided to ignore its effects in our own lives. We chose to love it instead of bending under its weight. If you’re out in a swamp every weekend morning, you’re not breeding and feeding. You’re in control. You need to stay out of nature’s way while you’re still young enough for it to ruin your life.

Or maybe I just thought that way because Stephen’s father had a pacemaker and it was the bane of his existence. That’s what he told me that day down on the dock: that he would die when the goddamn battery finally ran the hell down. In the private language shared by the extended family of western civilization, it had become impossible to connect nature and death. Nature was the locus of eternal recurrence, the seasons like coiled springs, the Lion King taking his father’s throne, the inexorable force of life that floods in and covers Surtsey with giraffes and hoopoes. Where it is apparent that there is no death, human beings are planed down to fear of failing technology: the loose seat belt that ratcheted too late and walloped Tiff, Jr. upside the head, the pricey polyurethane condom that was supposed to be so great and created her in the first place. We failed technology when it needed us most. The beaches were disappearing not because the oceans were rising, but because we hadn’t built the right walls to keep them out. We needed storm cellars and snow tires and environmentally friendly air conditioning. I needed to get to thirty-five without having a baby and then blame IVF. And meanwhile, nature itself was dying, one life at a time.

After two years in Berne, Stephen was still working on two migratory ducks. Two pretty common ducks actually, so it was a mystery why he didn’t have them yet. We would go out every Sunday morning to one little body of water or another and see everything but these damn ducks. He desperately, in his opinion, needed someone reliable to tell him where to find the ducks. So at long last he joined the Swiss Society for the Protection of Birds. He started entering his backlog of observations on ornitho.ch instead of just lurking. Four weekends in a row he went out with one of them instead of me. He didn’t make any mistakes.

They had a thing for English speakers. England is the mythical Eden where every rude mechanical knows what is nesting where in his garden and woodcocks eat out of your hand, and America is the land of the citizen scientist and the bag limit. American hunters shoot five ducks in the first five minutes of the season and rest on their laurels. Models of reason and restraint.

So they trusted Stephen, even though birders under fifty were reportable to the Swiss Rarities Committee. Stephen knew his birds. They gave him a piece of protected marsh to count birds in, every Sunday in winter and once a month in summer. They promised him his ducks had an excellent chance of turning up. So he sat there behind his spotting scope looking at mallards until about mid-January and then decided maybe something was wrong with Sundays. He tried Saturday and saw about two thousand birds—various rails, fudge ducks, tufted ducks, common pochards (female), red-crested pochards, and a juvenile eagle.

The next morning he asked me to come with him. He wanted to take off at five o’clock. I forced myself. We didn’t have to look long for the guy. We heard him. He was hunting from a boat on the other side of the creek.

“No way!” Stephen said. We could sort of make him out dragging the boat up into the reeds, and heard him call his dog and start his car. It was Sunday, with no birds anywhere in sight except the ultimate in trash—those sinister little chickadees everybody feeds, who hang around all winter and get dibs on the nesting sites the good birds need. Luckily ninety percent of them die anyway of hunger and cold.