Читать книгу The Legacy of Eden - Nelle Davy, Nelle Davy - Страница 9

Оглавление1

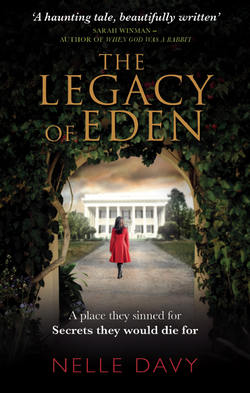

TO UNDERSTAND WHAT IT MEANT TO BE A Hathaway you’d first have to see our farm, Aurelia.

If my family’s name is familiar to you, it may be that you have either already seen it, or at least know something of its reputation. In its day our farm was notorious for being one of the most prosperous estates in our county in Iowa. An infamy only surpassed in time by that of the family who owned it.

I have spent the past seventeen years trying to forget it, forget my family and forget my past. For seventeen years I was given a reprieve, but after that length of time, you stop looking over your shoulder and you forget how precarious your peace is. You take it for granted; you learn to bury your guilt and then you convince yourself that it will never find you.

And then he died.

My cousin Caledon Hathaway Jr. left this earth in late October at the age of forty-five. The cause of death was cirrhosis of the liver. As seemed to be the curse of all Hathaway men after my grandfather, he would die young and alone and how he was found I do not know: he lived with no one and by then Aurelia had ceased to be a business and had become merely a vast space of withering land. Though a notice was placed in the local newspaper, his death was mourned by no one and his funeral attended only by the priest and an appointed lawyer from the firm who handled our family’s assets. His body rested in the ground, at last unable to hurt or harm anyone else, and that should have been the end of it.

But then eight months later, at ten to three on a Thursday afternoon, I received a letter. I settled into my armchair next to the window, my hands still stained with streaks of clay from the morning’s work in my studio. Ever since I left art school I have dedicated myself to sculpture, though it has only been in the past five years that I have made a decent enough living from it in order to do it full-time. Before that I was like any artist-cum-waitress, come every and any menial job you could find. I don’t earn much but I get by and as I fingered through the array of bills and fliers, the stains of my morning’s endeavors trailed across the envelopes until I came across a stark white one, different from the others in its weight and the crispness of its paper. It bore the mark of an eminent law firm whose name seemed familiar to me, but I thought nothing of it and slit open the mouth of the letter with my finger. Why wouldn’t I? I had forgotten so much—or at least I had pretended to.

By the time I had finished reading it, the damage had been done. I looked up from the typescript to find my apartment an alien place. Sunlight was streaming through the windows and reflecting off of the counter surfaces and wood floors. I could feel a prickle of sweat on the back of my neck and my mouth tasted hot and sweet with what I realized was panic.

I rushed to the bathroom and was violently sick.

Pushing myself upright I brought my hands to my face and then ran my fingers through my hair, clawing the strands back from my forehead. I caught sight of my phone and even though my stomach was filled with dread, I had to know, I had to know if they have been told. The letter said that they had tried to contact other members of the family. Who else, who else? I closed and reopened my eyes but it was no use. As soon as I began the thought, they swam across my vision, the living and the dead, diluting the reality of my kitchen with memories I had striven to bury for nearly two decades: my grandmother in her caramel-colored gardening gloves pruning her roses; my father throwing water over his head to cool himself off so that his great mop of blond hair slicked back, grazing the top of his shirt; Claudia in a white two-piece with her red sunglasses; my uncle Ethan shaking a cigarette out onto his palm from a pack of Lucky Strikes. I leapt away from the counter and ran into the studio. I darted around my sculptures to my desk and rooted through the drawers until I found the battered Moleskin address book and flicked through the pages until I found her number.

Where would she be now, I thought as I dialed her number? Is she even home? I knew she had gone parttime at the clinic since she had the girls, but I don’t know her shift schedule. But my thoughts were abruptly cut off as she picked up on the fourth ring.

“Hello,” she said, slightly breathless.

I opened my mouth to speak.

“Hello?” she said again.

There was a pause. I pictured her hanging up.

“Hel—”

“Hello?”

“Hello?”

Our voices overlapped. She withdrew. In the interim I somehow managed to ask, “Ava?”

She was shocked. I heard a sharp intake of breath. I said her name again.

“Meredith,” she said finally and then sighed with impatience. I wound the telephone cord around my finger at that and squeezed.

“Can you talk?” I asked

“Yes.”

“I thought you might have been at the clinic. I wasn’t sure if you were in.”

“I just finished a shift.”

“Are the girls around?”

“I’m alone, it’s okay.”

I closed my eyes and swallowed.

“Good, I—I need to talk to you. It’s—”

“Is this about Cal Jr.?” she asked abruptly.

My eyes flew open. I felt winded. My voice, when it came out, was harsh, animal.

“How?”

“The family lawyers called me.”

“When?”

“A few days ago.”

“Why?”

“Same reason I suppose that they contacted you.”

“They did not call me,” I said, looking down at the letter, which was crumpled in the fist of my hand. “They wrote instead.”

“I told them straight out I didn’t care. Not about him dying, not about the farm or how he had driven it so far into the ground it was halfway to hell. They talked about my ‘responsibility.’ I told them I had done above and beyond more than my duty by that place.”

I bit my lip so hard I thought I tasted blood.

“I suppose I was a bit harsh,” she said reflectively, “but I got the feeling that they would just keep calling if they thought they could get anywhere. I guess that must have been why they tracked you down.” She paused. “Have you heard from Claudia? Do you know if they contacted her, too?”

I thought about our eldest sister, probably dismissing shop assistants with a bored wave of her hand in some mall in Palm Beach.

“No, but she has a different name now. She’s married.”

“Did not stop them from getting to me. Or to you, or don’t you go by our mother’s name anymore?”

I swallowed hard at the reproach. “No, it’s still Pincetti.”

She snorted. “And there was once a time when Hathaways were crawling out of our ears, now none to be found. I suppose I was the first person you rang when you got the letter, was I? I am so touched. I wonder why that would be?”

I closed my eyes, blocking out the orchestra of sounds from the taxis and crowds on the road below and the various cacophony of voices that rose in a fog from the streets. I forced my mind to blank, to hold my breath in my chest, to keep everything still.

“So you knew then?” I somehow managed. For a moment I thought she had gone, as there was only silence and then, “Yes.”

I digested this. “I see,” I said and I did, with painful clarity. This was a mistake.

“I told them I didn’t want anything to do with it,” she volunteered. “They could do what they wanted.” She gave a small laugh. “They even asked me about funeral arrangements. I told them the only way I would help would be if I could make sure he was really dead.”

I winced. I hate this side to her, especially because I am part of the reason why it is there.

“It’s all gone you know? The farm …” she began. “In the end it was riddled with debt. They’re going to sell it, did you know that?” She stopped and when she began again, her voice broke. “It was all for nothing and she’ll never know it.”

There was a pause.

“What will you tell them?” she asked eventually.

“Huh?”

“What will you do?” Her voice was careful, deliberate, and I realized with a small shiver that I was being tested and that she had no expectations that I would pass.

“I suppose I will have to call them.”

There was a silence. There was nothing for a moment; just a blank and then when she next spoke her voice had degenerated into a repressed scream of fury.

“Why?!”

This time I spoke without thinking, so that what I said not only surprised me because of my daring, but also because it was true.

“I guess I’m just not ready to walk away yet.”

Even to my mind they were an interesting choice of words. They hung there in the silence between us. I waited for her to speak and I could tell even in the pause how much she wanted to attack me, to use my words as a noose and hoist me up, legs kicking, desperately searching for ground.

“I have to go. I need to pick up the girls,” she said.

All of a sudden I was exhausted. It would never end, I thought. There was still too much damage left to inflict. I had long since ceased to engage in this trading of blows. I had marked her once and that was enough. Nearly two decades later it was still pink and raw, but she was not yet finished.

“I’ll call you back,” she offered.

“Okay,” I said and we hung up. Even as we did so I knew she wouldn’t call back. As if we were still children, she spoke again in code, a code she meant for me to decipher:

You did not do as I expected. You failed me—again.

Aurelia. I don’t know what it looks like now. It has been years since I last saw it from the back of a car window, but I don’t fool myself for an instant that even if the place was rotted out and the fields of once bright corn are now nothing but broken earth, that I wouldn’t still feel the same pull to it, a need to do the unspeakable for it.

That is one of the reasons why I have never gone back.

Why does it have this effect on me? Because of this: regardless of my mother and her lineage, I am a Hathaway. Even though I have taken her maiden name (and no one except my college alumni association asking for money, or Claudia in postcards, refers to me as anything else) it does not matter. I may live in New York, have changed my hair color, name and friends, but tug at the right thread and all this carefully constructed artifice will fall away.

Blood will out.

In its heyday, my family’s farm was impressive: it stretched three thousand acres when the average farm was about four to five hundred. But more than its size, our farm was infamous because it was unusual. Unlike any farm in our county, or indeed any farm that I have ever heard of, my grandmother took it in hand and developed it into something more than just a business, but a thing of real beauty. She did the unthinkable, and even more astonishingly, it worked.

Farms are meant to concentrate solely on that which will maintain them: crops, livestock, tools. They are a place of work and where I come from, the farms that were considered the most impressive were those that embodied this: well-tended fields, a full harvest, up-to-date machinery. This was the attitude of our fellow farmers and their own farms reflected this. If there had been such a thing as Farm Lore, this would be it.

But my grandmother wanted more. She didn’t see why she shouldn’t and somehow, to the puzzlement and then mockery of their neighbors, she succeeded in convincing my grandfather, the son of a seasoned farmer who had been raised on all the principles I have just described, to ignore what he had been taught and bend to her will.

The result was months of gossip, whispers in the grocery store, lingering stares and tight smiles when they were passed on the street. The farmers themselves made fun of my grandfather behind his back; lamented his impending ruin to each other and begged him to his face to curtail his wife’s madness. You must understand, our town was a community, and that meant that everyone had a small stake in everyone else’s business.

“It’ll end in tears,” they said, and secretly hoped.

In little over a year, my grandmother decided that her initial vision was completed enough to her satisfaction and she threw a party. My grandfather, Cal Sr., was relieved—he saw it as a peace offering. She let him believe that.

How can it be so easy for her? I thought, as I sat in my studio, my conversation with Ava repeating in a continuous loop through my head. She who, unlike me, spent years forcing herself to remember when I was struggling to forget. The light was beginning to die outside, eager lamps from the streets sharpening against the encroaching dark. I sat in the corner of my room, surrounded by the half-formed clay models, whose shadows threw deformed specters on the walls behind them. I could tell as we spoke that unlike me she did not see an arched sign hung between two columns of oak with the farm’s name written on it in curlicue black lettering or the gravel paths that wound through sculptured green lawns on which were planted pockets of flowers. It was a path that swung down to a sloping mound on top of which stood a house so impressive that seventy years ago, when it was first revealed to our neighbors, it caught the eyes of every guest carrying their various dishes of dessert and dressed salad and forced them to stop.

The old house where my grandfather had been raised, the one that had been just like their own, had been torn down. In its place, built in a mock colonial style, was a tall square building. What struck them first when they gazed up at it was the color: it was white. Even before they entered it they knew on sight that it was a place of polished woods with the smell of tall flowers in clear vases.

No, my sister did not see this and I knew she would not have cared to do so even if she had.

She did not see the rose garden with American Beauties puncturing the trellis walkway or the grove with the fountain of the stone god blowing water from his trumpet. Her memory had pulled down the shutters onto all the things my grandmother had fought so hard to accumulate and on which she had lavished such loving attention. I could hear in her voice, how little she cared now, how much she almost rejoiced in its demise. What had once been a thing of beauty abundant with fields upon fields of corn, which in the summer took on such hues of yellow mixed with orange that you could be fooled into thinking you were viewing the world through a haze of amber, was now an empty husk, reflecting only the various corruptions and losses of its last and most destructive owner.

She did not always think so. If you had seen the farm in its golden age, you would have called it a halcyon and known in your heart that to live there was to be happy. Secretly everyone thought so. My grandmother knew it and relished it. I could not fully understand why at the time. Her reaction to people’s envy and admiration was almost victorious. Only later did I come to realize how she had longed to be at the receiving end of such jealousy, that she had geared her life toward that moment. It had for so long been the other way around.

Can you understand? Can you discern even from these fragmented recollections the hold that place could have? Why those who lived there would do anything to protect it regardless of the consequences? It was stronger than the bonds of community, this love, stronger in the end than that of family. It affected all of us. Not the same, never the same, but it always left its mark and you knew then who you truly were and why you bore your name.

On the rare occasions my sister and I have talked since resuming contact a few years ago, our conversations have tiptoed around her bitterness—her, I should say, justified anger. Out of fear or diplomacy we have steered clear of anything that might have forced us down a path on which we would have to confront what is between us. I have done this dance mainly on my own. There were times when I think she would have gladly allowed things to degenerate into the spectacle of recrimination and blame that I so desperately hoped to avoid, but she never pushed it. When the time came, and I think we always knew it would, she would have nothing to fear. She was the betrayed, not the betrayer.

And now, here we finally are, because the one time when she expected me to revert to type and walk away I wouldn’t. The irony was not lost on me as I put the phone back on its rest. I know what she thinks—that I’m being deliberately contrary, hurtful, cruel. The rational part of me knows I have no right to blame her for thinking this—haven’t I proved myself to be all these things already? But I am still furious with her, because I so want to be able to do what she is asking and leave the farm to its fate with no regrets, and I can’t. Then I could show that what happened—what I did—was a mistake, it wasn’t me. I can change. I have changed.

I was calling for her. It was I who had offered to find her.

Oh, God, if I had never … if I had never opened that letter today, if she hadn’t told the lawyers she had wanted nothing to do with them, if Cal Jr. had never inherited the farm, if I’d done the things I’d believed I was capable of, if I hadn’t been capable of the things I’d done, if … if … if … somewhere out there, all the potential versions of my life floated on parallel planes. In one I never went out that night, in another more likely alternative, she does not put down the phone. Instead she stays on the line. We talk for a long, long time.

She listens.

She forgives me.

Do you believe in ghosts?

I didn’t until I started living with them.

Two days have passed since the letter arrived. I walk past my mother sitting in my armchair mending my pinafore, or my father at the fridge humming to himself as he scans my feeble purchases of organic whole foods. The walls between my memories and reality are disintegrating and everything from my past that I have tried to push back, now rushes forward to escape.

Once while on the way to the bathroom, I passed my cousin Jude, who I have not seen since I was ten. He cracked a hand on the back of my legs. “Toothpicks,” he chortled; I gave him the finger.

Part of me is terrified. I wonder if I am losing my mind. But I find their intrusions oddly comforting. It is like turning up at a reunion I have been dreading only to remember all the things we had in common, all the memories that made us laugh, and I am reminded of a time when it was easy to be yourself.

At one point when I was flicking through the channels and stumbled on a soap opera my grandmother used to love, I hesitated. Even though I knew it was crap, and I have never watched it, I left it on for her, imagining she was behind me, waiting to hear her slip past and the soft creak of the wicker chair as she settled down to watch it. Just before it broke for commercial I said aloud, “This is madness.”

Swift in reply, she answered, “Only if you expected a different outcome.”

It was at this point that I decided to call the lawyers.

“Good afternoon, Dermott and Harrison, how may I help you?”

“Yes, this is Meredith …” I hesitate. What name do I use? And then with a sense of weariness I think, what’s the point in trying to pretend. “… Hathaway. May I speak with Roger Whitaker, please?”

“Will he know what it’s regarding?” the receptionist asked.

For a second I was struck dumb. “Yes.”

I was sitting down this time. I took a deep breath and leaned back into the headrest as I was put on hold. After a few seconds the line was picked up and a male voice answered the phone.

“Miss Hathaway, so good to hear from you.”

“Is it?” I asked.

“Of course. I assume you’ve had time to think over what we detailed in the letter?”

“What part? The part where you told me my cousin was dead or the other bit where the farm’s going to be sold off and auctioned to the highest bidder to settle against his debts?”

“I know this is difficult to take in—” no, I’ve been waiting for this for seventeen years “—but we think perhaps it would be best if we spoke face-to-face about this. One of our senior partners was a friend of your grandfather’s. He knows how important the farm was to your family.”

“Was it?”

“Excuse me?”

“Was it important to us—I mean how many of us had you tried to contact before you found me? How many times did you get hung up on or ignored? Probably got cursed out a few times, too, huh?”

The voice was deliberately gentle at this point. “We were aware that there had been a significant rift between several family members. We know this is a delicate situation and for the sake of your family’s past connection with this firm we wanted to make the process as smooth as possible ….”

I saw that I was in for the lengthy legal homily.

“You can’t.”

“I don’t think that—”

“You can’t ever make it better. You can’t make it nice and easy or simple, so do yourself a favor and don’t try.”

There was a pause. “There was talk here that perhaps it might be more effective if you or a family member could sign over the responsibility of handling the dissolution of the farm and its assets to us. Of course this could prove to be difficult, considering that there is no direct claimant to the farm and others could contest the process if they should hear and—”

“No one will.”

“Well, uh, even so there is the matter of personal items, artifacts. We weren’t sure if someone would want to come down and sort these out from what should be sold with the farm and what would be kept.”

I saw my childhood home, the one a mile down from the main house with its yellow brick. Suddenly I was in our blue living room with the window seat behind the white curtains I used to hide under while I perched there waiting for Dad to come home.

“Of course.”

“When can you come down then?”

“What?”

“When would you like to come to the farm and do this? The sooner the better, to be frank. I don’t know if you are working, or if it would be a problem for you to take time off—”

“I work for myself. I’m an artist—a sculptor actually.”

“Excellent, then when shall we set up an appointment?”

I opened my mouth, suddenly utterly bereft. I raised my eyes from the floor and shuddered. They had lined themselves up all around me in a crescent of solemn, knowing faces.

“I don’t know.”

Our farm was on the outskirts of a town surrounded by the farms of our neighbors: people whose children we played with, whose families we married into, whose tables we ate at. Together our farms formed a circle of produce and plenty that enveloped our small town, a hundred and seventy years old with its red-and-white-brick buildings and thin gray roads. Simple people, simple goals, old-fashioned values: this is where our farm is still to be found. I had not seen it in nearly two decades, but as I looked at the crowd of faces glaring at me from the other side of the room, I realized with a thin sliver of horror I had no choice, I would be going back. And I shuddered so violently, I had to clamp a hand over my mouth to stop myself from crying out.

“We’ll leave you to think about it. But please—” his voice retracted back into smooth professionalism “—don’t take too long.”

It took me three hours to find it. There was a lot of swearing, I tore a button off of my shirt and scratched my arm, but eventually I sat cross-legged on the carpet and smoothed the crackled plastic of the front before I opened the album.

Ava had packed it in my suitcase the night before I left for college, the night I found her in the rose garden. I had opened my trunk in my new dorm to find it slotted between my jeans and cut-off shorts. I couldn’t bear to look at it for a long time. I had left it in the bottom of the trunk and when I had to repack for Mom’s funeral, I had tipped it out on the floor, daring only to look at it from the corner of my eye. I am a firm believer in what the eye doesn’t see, can’t be real. That was why, much to my mother’s deep disappointment, I became a lapsed Catholic.

But this time I flipped back the covers and stared. I drank it in. The photos had grown dull with age. The colors, which were once vibrant blues and reds, were now tinged with brown and mustard tones. I slipped my fingers across the pages, watching the people in them age, cut their hair and grow it out again. From over my shoulder, my father leaned down and stared at himself as a young man on his wedding day. The light behind my parents was a gray halo surrounding the cream steps of the New York City courthouse. They had married in November, just before Thanksgiving, and you could see behind the tight smiles, as they stood outside in their flimsy suits and shirts, how cold they were.

“Phew, wasn’t your momma a dish?” he said.

And she was. She wore her hair in the same way she would continue to for the rest of her life: center part, long and down her back. A perpetual Ali McGraw. Decades after this photo was taken, she would be widowed, her children would be scattered and broken, her home rotted out from beneath her. In her last moments, did she think of this? I don’t know. I wasn’t with her, only Ava was there.

She was not alone if she had to face her past and all its demons. And neither am I. I could feel them all pressing against me: the smell of my father’s breath … chewed tobacco and Coors beer somewhere to my left.

I took my time with the album, even though inside I started to scream. My hands trembled but I continued to turn the pages. Each new memory sliced its way out of me, taking form and shape with all the others. I didn’t mind the pain—it was just a prelude to the agony that has been biding its time for the right moment and now it was almost here. With one phone call it was as if all those years of running away were wiped out in an instant. My life is a house built on sand. That should have made me sad but it only made me tired. I turned another page. We looked so normal. In many ways we were, except all the important ones.

I flicked the page and saw my aunt Julia, whom I never got the chance to meet. Her hair was still red, before she started to dye it blond. From what I’ve heard from the strands of people’s covert conversations, Claudia was a lot like her.

And then I looked up from the album and saw him standing there, the cigarette smoke separating and spiraling above his face. He was named after my grandfather, who was lucky enough never to realize what his namesake would grow into.

“Are you in hell, Cal?” I asked him.

He laughed at this. “Aren’t you?”

“What do you remember?” I asked, suddenly urgent.

“Same as you,” he said with a sly grin. “Only better.”

“Don’t listen to him, honey,” my father said, lifting his chin in disdain.

Cal Jr. shot him a look of pure hate. “How would you know? You weren’t even there!”

I stood up and walked out of the room. This is it, I thought to myself, I’ve snapped. I’m finally broken.

“You’re not fucking real,” I suddenly shouted.

“Dear God, girl, still so uncouth,” my grandmother said, stepping out from the kitchen, her tongue flicking the words out like a whip. “I always told your mother she should have used the strap on you girls more often, but she was too soft a touch.”

I turned around to face her, my fists clenching and unclenching by my side. “You—if you hadn’t—”

She turned away from me, disdainful, bored. If this were all in my head, what did that say about me?

“Enough excuses, Meredith.”

I was shaking so hard, my voice tripped over itself.

“You were a monster, you know that? A complete monster.”

“Made not born,” she said and looked at me knowingly.

“Oh, no—” I shook my head “—I am nothing like you.”

“No, Merey—” and she smiled “—you exceeded all of our expectations.”

I took a step toward her—toward where I thought she was.

“I’m going back to the farm. To sell it, to take what’s left of your stuff and hock it at the nearest flea market.”

“Oh, Meredith.” She sighed. “You’ll have to do better than that. Have you learned nothing? In terms of revenge we both know you can do so much more.”

I shook my head and rubbed the heels of my hands into my eyes until the light grew red.

“You’re not here,” I said again, but even so I could feel the light pressure of her hand on my wrist.

“Neither are you,” she whispered.

I opened my eyes and lifted my head. There: the fields on fields of cereals and golden-eared corn from my memory, from my dreams. They lay before me, an ocean of land, the colors all seeping out in a filter of gray.

Exasperated, I finally asked her the question I knew she had been longing for. “Why are you even here?”

“Darling.” She chortled, suddenly filled with unexpected warmth. The silk of her green dress grazed past my arm as she came to stand beside me. “We never left.”