Читать книгу Sing Down The Stars - Nerine Dorman - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеThe Den was on the outskirts of the Western Calan City barrens, near the fens, which meant that the air was always full of biting insects. The barrens was a no-man’s land, where old wrecks and rubble created a haven for those who weren’t Citizens. Every year as Calan City grew, it pushed its barrens just that little bit further, a spreading canker that blighted the remaining wild lands. Yet to Nuri, this wasteland was home.

She knew every little side street and alley between the stilt-legged shacks, and could run them blindfolded if need be. Stars above, she could run all the roofs too. The Den itself had been built from old trams – three, in fact – that leant drunkenly against each other to form an enormous tripod. It nestled between Mama Ria’s Tea Room (constructed out of old shipping containers and trimmed with the outer shell of a Heran ore freighter) and a Khu-Khut hive (four weird, mud-daubed cones nearly as tall as the Den, embedded with bits of broken glass).

Shiv slipped their pod into the Den’s entrance without even a whisper of a bump, and they all clambered out, grumbling and grumping. Nuri stretched, feeling all the kinks of the run.

G’Ren bumped past her, hard enough to make her stagger.

“Oi! What was that about?” she called after him.

The J’Veth drone flipped a rude sign over his shoulder and stomped up the stairs to the common area, leaving her alone with Shiv.

Shiv’s third eyelid slipped slowly over her large black eyes, her tiny mouth pursed in annoyance. “What bug crawled up his cloaca?”

Nuri shrugged. “I think he’s peeved because I took too long.”

“You tipped off security,” Shiv said. “That’s not cool. I struggled to shake them.”

“I know. Sorry about that.” Nuri huffed out a sigh and stretched, then she patted her pocket. The pin was still there.

“I hope whatever it is, is worth it,” said Shiv. “Can I see?”

“Um, I’d best go up to see the boss-thing,” Nuri replied.

“Spoil sport,” Shiv murmured, busying herself with linking up the pod to its power source.

Nuri hurried up the stairs, unaccountably nervous. G’Ren was most likely already telling Vadith everything Nuri had done wrong.

Nothing I can do about that now.

This time of the morning the common room was near deserted, the hammocks dangling from the interior scaffolding empty. Most of the pack were out running, and the few who were in huddled on couches plugged into their VR sets or playing games of Tisk. The little ceramic discs clattered like bones on table tops.

Vadith’s quarters were on the mezzanine section right at the top, and Nuri clambered up the ladder in double time. As expected, G’Ren was squawking, and her name cropped up twice before she stepped onto her boss’s level.

Vadith was large for a Heran, which meant he was two heads shorter than Nuri. She liked the fact that she now looked down on him, but that didn’t stop him from reminding her where her place was – at the bottom of the pecking order in his pack.

His grey skin made him all but blend in with the hide-covered daybed upon which he reclined, blinking at her with his large, liquid-black eyes while he sucked on a gizza pipe. Beneath the dim strip lights, his complexion looked pasty even for a Heran, his short, skeletal limbs at odds with his pot belly and oversized oval head. G’Ren sat on stool to Vadith’s right, his skin gone peach-coloured in places, which suggested he was well pleased with himself. All six of his facial tentacles quivered in poorly suppressed mirth.

Nuri sighed, trying to keep her shoulders straight.

“I’ve got it, boss.” She reached in her pocket, overcome by a sudden reluctance to surrender the trinket.

Vadith put down the pipe’s mouthpiece, puffed out a plume of smoke and clapped his hands. “Well, bring it. Don’t be tardy.”

She strode forward and withdrew the pin. Vadith snatched it from her hand before she had a chance to examine it.

“Yes, yes! This is exactly it,” he crowed, stroking the little dragon with long, grey fingers.

“If I may ask,” Nuri started, “out of all the items there, why this one? There were rubies –”

“I can get rubies at the market,” he snapped. “This” – he held up the item to the light fittings – “is irreplaceable. An ancient human tribe called the Celts made this. It’s the real deal.” Vadith smugly pinned the item to his jacket. “And this is where it will stay.” His tiny mouth squinched up with pleasure.

Realisation hit Nuri. “You made me and G’Ren risk our necks for a trifle?”

Vadith straightened, his left hand protecting the dragon pin. “There is more to this game than merely profit, child.”

“That was top-class security you had us breach,” Nuri continued. “We almost got caught.”

“I told you we didn’t have much time,” G’Ren broke in. “And you had to waste it.”

Nuri fixed him with a glare. “Not now.”

“This, Nuri, was a straight in-and-out job, and you had to gawp like a glimmer bug at a light fitting,” Vadith chastised. “Most unprofessional. You could’ve gotten caught, and then what?”

“But we didn’t,” Nuri said, hot shame burning her face.

“Not this time.” Vadith cleared his throat. “You’ll be on bathroom duty for two weeks. Perhaps scrubbing the drainage outlets will give you time to reflect on the importance of teamwork.”

Nuri swallowed back her indignation. The last time she’d given Vadith lip, he’d extended her bathroom duty to an entire month. It had taken a week to get the grime out from beneath her fingernails afterwards.

Vadith’s puckered little mouth stretched into what he might consider a smile, but what she thought looked more like the back end of a fen-flit’s larva. “Do we have an understanding?”

Nuri focused on the scuffed toes of her grip-boots. “Yes, sir.”

“Good. Dismissed.” Vadith sniffed. “Now, G’Ren, I am well pleased …”

Nuri didn’t stay to hear more.

Bathroom duty for two weeks – that was a special brand of awfulness. The others would make sure to dirty things up even more. They were like that. Nuri’s chest felt tight, and she scrubbed at her eyes with the back of her wrist. It wouldn’t do any good to cry coming down the stairs. No sign of weakness among the pack, the unspoken rule.

What she did need was to go for a run. Maybe as far as the north-western border before Flint’s territory at the ruined warehouses. An hour out, then back again before sunrise. Maybe she’d pick up useful intel or loot along the way. Fortune favoured those who took initiative.

“Where you goin’?” Shiv called as Nuri leapt up onto the hatchway.

“For a run.”

“Tonight’s close call not enough for you?”

“Oh, sod off.” Nuri pushed herself from the balcony and landed solidly in the alley between the Den and Mama Ria’s.

The ground was slightly squelchy from the previous afternoon’s rains. The ancestors alone knew what else festered in the muck.

If she had more of a spine, she’d stay and deal with the ribbing she’d get from her pack-mates. By the time G’Ren came down from his little chat with the boss, the story of how Nuri had nearly botched the entire mission would be the talk of the Den. Everyone who came in would hear the news second- and third-hand until the story was so blown out of proportion, you’d think Nuri had accidentally on purpose set the entire city on fire.

The snide comments about her muddied ancestry would come into play too.

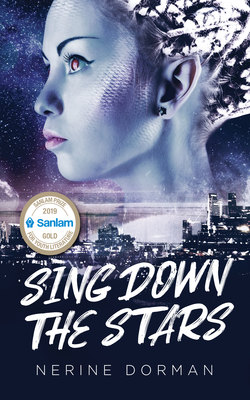

It didn’t help that Nuri wasn’t quite human. Or any known species for that matter. Which only added to the teasing. Humans didn’t have a fine spray of translucent scales on their upper arms and cheeks. When Nuri was younger, this had looked like glitter, but now that she was nearing adulthood, actual scales were forming. They gleamed like mother-of-pearl in a certain light, and she supposed they could be pretty, if it weren’t for the fact that her skin had no pigment. She was as pale as wax, and her dreadlocked hair was bone-white. It looked as if someone had stripped all the colour out of her with industrial-grade bleach, and she hated it. The fact that her ears were pointed too, and her teeth were a smidgen too sharp, had earned her the nicknames Monster and Fangface.

Everyone in the pack teased everyone all the time, but for some reason the nicknames stung her that little bit more, even though she tried to hide it. What were words, after all?

About the only thing she even liked about herself were her eyes. The irises were dark red, verging on indigo, with little flecks of violet in them, almost like a nebula.

Vadith said she must have a nocturnal species in her DNA, but Nuri didn’t burn in sunlight any worse than the other lighter-skinned species. She just had to wear shades when she was outside during the day because her eyes were unusually sensitive to light, and she knew for a fact she could see as well in the dark as one of the Mahai-kin. So there was that.

Nuri pulled her hood down low and started running. As she approached the dead end, she dragged herself up onto a stack of crates and followed the boundary. Her path along the wall was a mere foot’s width, but that was fine. Up here, on the rooftops, she was the mistress of her surroundings, lifted from the dirt and detritus into a world of buzzing neon and flashing LED screens.

Calan City’s lights became their own constellation, shimmering screens showing windows onto other worlds. Trains snaked along their rails, and every ten or so minutes yet another spacecraft gained clearance from the port to the north. The city never slept – the muted roar of thrusters, the wail of sirens and the ever-present hum of power drives kept up a constant drone. No matter where Nuri went or how high she climbed, there was no silence. No quiet. The air tasted of burnt plastic, dust and despair.

Her goal for the morning, before sunup, was to reach the old relay station. It was right on the edge, before the fens, abandoned because the ground was subsiding and new tech had made the station obsolete – at least until someone found some value in the structure.

None of the barrens-folk would set foot near it. The oldies said the place was cursed, and the kids only came here on dares. The station’s single aerial was listing heavily to the west, and kaza weed had swamped the walls in a green tide. The tiny, trumpet-shaped blooms were still open, releasing their sticky-sweet scent into the muggy air, where fat white moths the size of Nuri’s hands bumped into each other – a strange mingling of ruin and nature.

Anything that might’ve been of value had been stripped away years ago, but Nuri loved exploring the cavernous space where equipment had once been bolted into the floor and walls. In her wildest imaginings she became her own boss and claimed the station. Any runners who joined her pack would become her friends – other youngsters who’d been picked on and made the butt of jokes.

Such dreams were what kept Nuri going.

She came here, too, because she could climb to the top of the aerial, which was the tallest structure outside the city limits. Some nights, she fancied she could see all the way across the fen to the next city over. When it was clear, she might glimpse the shimmer of lights, and she’d wonder if there was another girl or boy sitting on a high place, thinking the exact same thoughts she was. It made her feel less lonely.

Rust flaked as she climbed, but Nuri knew exactly where to place her hands, how much weight each bar could take before she needed to shift. The aerial was tall – more than four-hundred metres. The higher she climbed, the freer she felt, lighter even. The wind mourned through the structure, making it creak and sway. Anyone else would be sensible not to ascend, but Nuri kept taking the chance.

Below her, as dawn broke, the barrens became a blanket of little lights skirting the shimmering, gleaming city with its gargantuan, glass-sheathed spires. Roads glittered with vehicles moving like sparks through veins, and she understood how the city itself was alive. Each day and night was an exhalation and inhalation, with the city centre the beating heart.

Nuri reached the top and clung to her perch, feeling the motion of the aerial stirring in the breeze, loving the chilly pre-dawn air that kept her alert, despite her exhausting night. If only she could stay here, away from the ugliness below. From up here, it all was so simple, so easy …

* * *

The song began as a low hum, more felt than heard.

At first, she thought it was the low whine of a power drive starting up, but the long, plaintive note rose and fell, ending in sharp blips and high-frequency clicks that went beyond her senses. The song wasn’t reaching her ears, but was resonating inside her, as if someone spoke on one of the psi frequencies. The small hairs on her nape prickled as the sound became heavier, drawing at her emotions and bringing tears to her eyes with the depth of its longing. The song was a river, dragging her in its current so that she turned her face to the north-east, across the fens.

How peculiar. How strange. The fens stretched on as an inky flatness before meeting the grey of the sky at the horizon. There was nothing out there for miles – just a tangled wasteland of vegetation and forgotten ruins.

The song wavered, ascending and descending, the wave-forms growing into staccato beats before ending in a plaintive whoop. A bass moan followed, drawn out and ascending again. Nuri’s teeth began to chatter as the sound vibrated in her marrow.

Out beyond the fens.

Come to me, it said.

“Ancestors above,” Nuri whispered. Beads of moisture formed on her brow, and her hands grew slick where she gripped the bars.

Another wave of the song hit her with so much force she almost let go – low howls that became bass notes died away to silence before returning as a wail. The desire, the wanting in the song was unlike anything she’d ever experienced before.

Would it hurt to investigate? If she didn’t, and this was a one-off event, would she curse herself forever for not trying?

And if it was something dangerous? Some sort of predator that lured unwary psi-gifted?

She’d be careful. She had to know more. So what if she upset Vadith.

She gritted her teeth as she began her descent.

What was out there? Nothing, really. Maybe more abandoned, half-built places. Wild things too, feral things. Nuri had no business beyond the barrens.

But every time her resolve wavered, the siren song would hit her with a fresh wave, vibrating through her veins and begging her to hurry. Come to me.

By the time her grip-boots hit the ground, she was already running, lungs burning as she pushed herself across the floor and out the gap. She barely paused to disentangle the thorny fronds of kaza that latched on to her hoodie.

Gravel shifted as she pelted down the embankment and squelched into the marsh, knee deep in the mire with the mud sucking at her feet. She knew this was madness, allowing such a strong psi-call to drag her off, but every time she slowed, tried to catch her breath, the call would intensify, and she’d find herself further away and not quite sure how she’d gotten there. Reeds shushed as she pushed through them. Flurries of water birds took to the wing, cackling and hissing at the disturbance. Nuri’s breath rasped in her throat, but she didn’t stop. The notion that she verged on a discovery that was bigger than anything she’d ever known dragged her forward with every sloshing step.

The fence, when she reached it, was rusted through in places, and much patched. Just beyond it was the true barrier – a twelve-foot ceramic panel wall, the kind that could be hastily erected. Except it had been here for a decade at least, and was shrouded in bearded moss and swathes of creeping polyp fungi.

The siren song had her follow the barrier’s undulations until she came to a place where the ground had caved in. At some point, a fen-mole must’ve made its burrow here, and whoever had built this structure either hadn’t noticed or simply wasn’t around to maintain it.

As it was, Nuri was just the right size to wriggle through, and she did just that – she was so far past the point of no return it hardly mattered. Besides, if she could outsmart security bots and trained militia, she could dodge whatever she encountered in this seemingly abandoned compound – she was faster than anyone else she knew, and could climb and hide better too. Also, she simply had to find out what manner of entity was broadcasting with such strength. She’d always had a degree of telepathic ability, but until now had never explored it. She could now feel so clearly …

Nuri emerged in a forest. Apart from the times she’d worked city botanical gardens, she’d never seen so many trees all close together. They went on and on. How come she’d never heard about this place? Surely someone would speak about a fenced property out in the fens? Her feet sank into deep mulch and she continued unerringly towards the source of the call. The air was thick with the organic scent of old leaves and the looped whistles of hidden amphibians.

The forest gave way to what looked like sports fields or training grounds. So much wide-open space – she’d seen stuff like this in the military recruitment ads. Green grass – as in the real stuff, and not synth.

In the soft, misty light of early morning, a pair of human, grey-uniformed guards, both armed with military-grade stunners sauntered past.

They were chatting about a sports match as they passed her hiding spot. They wouldn’t see her if they didn’t know to look for her, and as far as she could tell she hadn’t set off any silent alarms.

What was this place? No known military bases were located within spitting distance of Calan City. Yet here Nuri was.

The siren call pulsed in her mind, and she nearly gave herself away before the two men rounded the corner of a single-storey, prefab building constructed from the same ceramic as the exterior wall. Whatever this place was, all the buildings Nuri could see looked as if they’d been erected by one of those mass fabricating machines. Clearly they hadn’t been intended to be here permanently but they’d been here long enough for the grey walls to be splotched with lichen. Weirder and weirder.

Using the stations of an outdoor obstacle course as hiding places, Nuri made her way towards the biggest of the buildings – a hangar like they had at the spaceport.

The song became jubilant, more urgent here, and Nuri hurried along the side of the building, keeping flush with the wall. How much closer did she dare go? The sun was nearly up, and there’d be more people up and about soon. Would she be able to leave without being detected? Mouth dry, she worked her way round to the back, where a door stood ajar.

How bizarre that the door was open, its electronic lock flashing the amber light of malfunction. Her curiosity dug its claws in deep, and Nuri slipped through the entrance into a reception area where a few desk terminals stood on standby. A coffee mug on one desk told her there were folks here during the day, so she’d better hurry up.

The tugging in her very soul had her crossing into a passage off to the left of the front desk. It was all rather industrial, with slick brushed-metal surfaces and faint strip lights running along both sides of the ceiling. Nuri passed three doors on her right. As she arrived at the fourth, the lights on the lock turned from red to flashing amber, and the door slid open.

As if someone was expecting her.

Cold all over, she halted, her heart about to jump out of her throat.

What am I doing here?

That moment of doubt didn’t have time to gather dust because the siren song dragged her over the threshold and into a cavernous room, empty but for the bizarre object situated on the floor in its centre.

If an enormous blob of liquified stone had been dropped to the ground from a great height, that would be an apt description of what she could see. In the low light, the malformed ovoid pulsed with swirling blues and greens edged with violet. The ground in and around a smallish crater in which the object nestled bristled with an array of jagged crystal javelins, many easily twice as tall as Nuri. The psi-energy flowing off it was so strong it set Nuri’s teeth on edge. Still, she couldn’t help but approach.

As she neared the thing, which was the size of a train carriage jutting diagonally out of the ground, the siren song became one of exultation. Rightness.

Puzzled, Nuri reached out; she was almost within arm’s reach. Everything hummed with power, warmth, beauty. Another step and –

A hard force struck from her left, driving the air from her lungs. Her instincts kicked in enough for her to roll, but then the pain hit, and all her muscles cramped as one.

Stun-bolt. She’d felt enough of those in her short life to know what it was that had hit her.

All she could do was lie there while men and women shouted, and bright lights flashed so that she had to squeeze shut her eyes against the sudden glare.

The siren song that had lured her ended so abruptly its absence hurt her head.