Читать книгу When Reason Goes on Holiday - Neven Sesardic - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

The Wisdom That Failed

“Many would be wise if they did not think themselves wise.”

—BALTASAR GRACIÁN

Should philosophers be kings, as Plato suggested? Or, to paraphrase William F. Buckley, wouldn’t it be better to be ruled by the first 2,000 people listed in the telephone directory than by the most illustrious of Socrates’ intellectual descendants?

The evidence presented in this book shows that, despite their declared love of wisdom, surprisingly many leading philosophers have shown embarrassingly poor judgment in their excursions into politics. The disastrous way some of the most influential contemporary philosophers have engaged in politics should make us think twice before following their advice. This also raises a question: How could people who are obviously very clever and sophisticated in a field that is intellectually demanding be so foolhardy in practical affairs?

Indeed, twentieth-century philosophers have a bad track record in choosing sides in some momentous political debates. Many contemporary philosophers have disgraced themselves by defending totalitarian political systems and advocating political ideas they should have easily recognized as distasteful and inhumane. To give just three well-known examples, Jean-Paul Sartre championed Stalinism and later Maoism, Martin Heidegger actively supported and celebrated Nazism, and Michel Foucault publicly expressed enthusiasm for Khomeini’s Iranian Islamic revolution.

How could the very people committed to gaining the deepest knowledge about the world and human existence get things so wrong? Could this have something to do with the fact that the three philosophers just named (plus many others with similar unfortunate involvements in politics) belong to the so-called continental tradition in philosophy?

The terms continental and analytic describe two different schools in philosophy that have been in conflict roughly since the beginning of the twentieth century. The distinction between them is notoriously hard to draw in clear and explicit terms, but philosophers usually have no problem assigning most of their colleagues into one of these two traditions. A provisional self-characterization of the analytic style of doing philosophy is the claim that the analytic approach “involves argument, distinctions, and . . . moderately plain speech” (Williams 2006, viii). In one of the best historical accounts of the rise and development of analytic philosophy, this approach is described as being committed “to the ideals of clarity, rigor, and argumentation” and to the goal of “pushing rational means of investigation as far as possible” (Soames 2003, xiii–iv). Basically, then, the trademarks of analytic philosophy would be clarity of thought, precision, and logical coherence, as well as the honest and persistent effort to avoid obscurantism, pretentious writing style and false profundity.

This opens the path for the argument that analytic philosophers are better protected from committing political blunders because of their training in clear and logical thinking, whereas continental philosophers, lacking this kind of training and consequently being prone to empty rhetoric, undisciplined thought, and obscurity, will be much more exposed to the risk of making fools of themselves in politics. This is what many analytic philosophers tend to think.

We Will Teach You How to Think, They Said

The American Philosophical Association (APA), which is heavily dominated by analytic philosophy, seeks to attract philosophy majors with the following message:

The study of philosophy serves to develop intellectual abilities important for life as a whole, beyond the knowledge and skills required for any particular profession. Properly pursued, it enhances analytical, critical, and communicative capacities that are applicable to any subject matter, and in any human context (APA 1992).

This is a remarkably strong and bold statement about the alleged effects of studying philosophy: The pursuit of philosophy is claimed to enhance students’ analytical, critical, and communicative capacities, which can then be applied to any subject matter and in any human context.

The main problem here is that the APA provides no evidence at all for the wonderful improvements in thinking that philosophy supposedly can produce. Moreover, many scholars actually insist that the currently available empirical evidence comes nowhere near to establishing such a sweeping and resolute causal claim. In contrast to the APA’s assurance that studying philosophy improves reasoning skills, psychologists tell us that after a hundred years of debate “the issue of whether generalizable reasoning skills transfer to reasoning contexts outside of formal schooling remains an open question in the opinions of leading researchers” (Barnett & Ceci 2002, 615; emphasis added). What the APA advertises is additionally problematic because it seems to promise something like “far transfer” (i.e., transferring what one learns in one context to other very different subject matters and contexts). And the prospects of achieving far transfer are notoriously questionable (see Holyoak & Morrison 2005, 788–90, and references therein).

All in all, therefore, it appears that the APA is involved in false advertising, which can be explained by ignorance, self-serving intellectual dishonesty, or some combination thereof.

In a recent discussion about the value of philosophy, the executive director of the APA, Amy E. Ferrer, said this:

Philosophy teaches many of the skills most valued in today’s economy: critical thinking, analysis, effective written and verbal communication, problem solving, and more. And philosophy majors’ success is borne out in both data—which show that philosophy majors consistently outperform nearly all other majors on graduate entrance exams such as the GRE and LSAT, and that philosophy ties with mathematics for the highest percentage increase from starting to midcareer salary—and anecdotal evidence indicating that philosophy and other humanities majors are increasingly successful and sought after in the business and technology sectors (quoted in Jaschik 2015).

Ferrer’s defense of the value of studying philosophy is fallacious. It is based on the logical mistake post hoc, ergo propter hoc. Briefly, the statistical correlation between studying philosophy and all these good outcomes does not mean that the former causes the latter. It may well be that those who embark on philosophy studies are simply smarter to begin with and that their subsequent success is in no way (or not mainly) the result of what they learned in philosophy courses.

This pretty obvious alternative explanation for the good performance of philosophy majors is not recognized by the APA as a possibility that deserves any consideration. The same blind spot reappears in a letter that was signed by three officers of the APA (including the well-known Stanford philosopher Michael Bratman) and published on the APA website. Again, the authors first provide statistical data about above-average accomplishments of philosophy majors and then jump to the conclusion that studying philosophy “trains students’ general cognitive skills, improves their ability to reason” and thereby “make[s] philosophy majors highly flexible in the job market” (APA 2014; emphasis added). The three italicized words all assert causal influence and they can be justified only if something more than a merely statistical correlation is provided. The fact that even very prominent philosophers do not sufficiently appreciate the warning that correlation does not imply causation—perhaps the most hackneyed principle of critical thinking—is not the best advertisement for the value of philosophy for critical thinking.

The British Philosophical Association (2016) also promises on its website that the philosophy student will develop the capacities to “think well about important issues” and “learn to be an independent and flexible thinker,” and that these skills will “both be of value throughout one’s life and in demand by many employers.” Again, no evidence is provided that studying philosophy can really bring about these magnificent effects. Moreover, given all that we currently know there is no good reason to accept these optimistic claims.

In 2010 more than a thousand people, including a number of well-known philosophers, signed a petition titled “Make Reasoning Skills Compulsory in Schools” (Burgess 2010). The petition was addressed to Michael Gove, the UK Education Minister. The petition urged the government to make philosophy classes compulsory from a very early age, arguing that this “would have immense benefits in terms of boosting British school kids’ reasoning and conceptual skills, better equipping them for the complexities of life in the 21st century.”

In support of this radical proposal they offered two pieces of evidence.1 One was a collection of articles written by a group of people, all of whom are philosophers and philosophy educators, and who—as we learn in the book introduction—were “all firmly committed” to the view that philosophy should be a compulsory part of the school curriculum (Hand & Winstanley 2009, xiii–xiv). Besides this highly biased source produced by true believers, the petition invoked a 2007 study by two researchers at Dundee University allegedly showing that “confronting core philosophical debates as the nature of existence, ethics and knowledge can raise children’s IQ by up to 6.5 points, as well as improve emotional intelligence.”

There are three major problems here. First, the public campaign to force all children in the UK to take philosophy classes essentially relied on only one scientific study. (Consider an analogous case: If two researchers announced that in their sample of 177 children, taking a certain new medicine was statistically associated with better health, would anyone seriously consider the proposal that, on that basis alone, all children in the country immediately start taking the medicine regularly?)

Second, it is unclear whether the supporters of the petition were aware that the authors of the study in question themselves explicitly cautioned the reader that the results “should not be over-interpreted or accepted uncritically.” (It is hard to think of a more extreme way to over-interpret and uncritically accept a study than to prescribe a national curriculum based on its tentative conclusions.) The authors pointed out that their study suffered from methodological imperfections and warned that sampling was not entirely random, that the possibility of the Hawthorne effect (also known as the observer effect) could not be ruled out and that differences between experimental and control classes could be influenced by factors that were not measured (Topping & Trickey 2007, 283).

And third, even if the gains were genuine, whether they would be sustained after the experiment ended would be unclear. Obviously there would be little point in modifying the national curriculum for elementary schools if the good effects dissipated soon after any such intervention came to an end (which frequently happens with reported increases in childhood IQ).2 So before starting a massive educational reform, it stands to reason that the durability of those effects should be confirmed in the first place, preferably by independent research teams.

Surprisingly, despite all these self-evident reasons against joining the campaign, a number of well-known philosophers (including Simon Blackburn, Jonathan Glover, Bill Brewer, A. C. Grayling, Duncan Pritchard, Peter Simons, Jon Williamson, Bob Hale, John Dupré, Robert Hopkins, Brian Leiter, Jennifer Saul, and Helen Beebee) not only supported the hasty and ill-thought-out proposal but were ready to defend it publicly by putting their signatures on the petition. Even more oddly, among the names of the supporters we also find leading philosophers of science who should have immediately realized that there is simply no way that the presented evidence could justify the extravagant proposal of the petitioners. (Two of those philosophers of science, Alexander Bird and James Ladyman, are past editors-in-chief of the British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, arguably the world’s best journal in the field.)

One would have expected philosophers to be careful about making such confident public assertions about philosophy’s benefits for two reasons. First, since it is obviously in their interest to spread the belief that studying philosophy pays off so well, they should be acutely aware of the possibility of self-deception. Second, they should be concerned about the well-being of their prospective students who could be lured into choosing philosophy by false advertisements, but might later come to regret their massive investment of time and money in something that does not lead to the promised results.

Russell’s Paradox: A Genius with a Streak of Foolishness

The belief that studying philosophy, when it is geared toward developing analytical skills and conceptual clarity, also enhances rationality and critical thinking in practical affairs of everyday life (including politics) dates from the early days of analytic philosophy.

In a book still frequently assigned to undergraduate philosophy students, Bertrand Russell expressed a similar view about the practical usefulness of philosophy: “The essential characteristic of philosophy . . . is criticism. It examines critically the principles employed in science and in daily life” (Russell 1912, 233; emphasis added). This sounds nice, but there was little trace of critical examination in many of Russell’s own actions and especially in his political statements. George Trevelyan, Russell’s undergraduate classmate at Cambridge, once said about him: “He may be a genius in mathematics—as to that I am no judge; but about politics he is a perfect goose” (Monk 2000, 5). Similarly George Santayana said: “Along with his genius he has a streak of foolishness” (quoted in Eastman 1959, 192). Illustrations of Russell’s political irrationality could easily fill a whole chapter in this book, but since many of these episodes are probably already widely known I will give only a few examples of his ludicrous political outbursts.

In an article published on October 30, 1951, in the Manchester Guardian, Russell said that the United States was as much a police state as Hitler’s Germany or Stalin’s Russia. He continued:

In Germany under Hitler, and in Russia under Stalin, nobody ventured upon a political remark without first looking behind the door to make sure no one was listening. . . [W]hen I last visited America I found the same state of things there. . . [I]f by some misfortune you were to quote with approval some remark by Jefferson you would probably lose your job and perhaps find yourself behind bars.

It should be stressed that Russell’s anti-Americanism and his political silliness date back to the time of the First World War. In his January 1918 article (for which he went to prison), he stated that if the war continued “[t]he American Garrison will be occupying England and France” (Russell 1918). This confidently predicted occupation of England and France by the U.S. Army of course never happened, but Russell did not allow himself to be embarrassed by such a silly prophecy. In the same article he claimed it was “completely false” that the mass of Russians were against the Bolsheviks (although in fact more than 75 percent voted against them in the election of 1917). He also said it was completely false that Bolsheviks dared not permit the Constituent Assembly to meet (although in fact the Constituent Assembly did meet but was expressly dissolved by Bolsheviks).3

On November 27, 1965, Russell sent the following message to the Tricontinental Conference (an event that took place in Havana in January 1966 and that was described in a report to the Committee on the Judiciary of the U.S. Senate as “probably the most powerful gathering of pro-Communist, anti-American forces in the history of the Western Hemisphere”):

In every part of the world the source of war and of suffering lies at the door of US imperialism. Wherever there is hunger, wherever there is exploitative tyranny, wherever people are tortured and the masses left to rot under the weight of disease and starvation, the force which holds down the people stems from Washington (quoted in Monk 2000, 467).

Russell biographer Ray Monk correctly observes that here Russell comes close to saying the USA “is responsible for literally every evil in the world” (ibid.). Although Russell was very old at the time, Monk argues that the senility excuse for his signing such statements is not convincing because a lot of evidence shows that Russell was “in full awareness of what he was doing” and that he “remained in possession of his mental faculties until his dying days” (Monk 2000, 455).

On June 11, 1966, Russell sent the following message to Hanoi:

I extend my warm regards and full solidarity for President Ho Chi Minh and for the people of Vietnam. I convey my great wish that the day may not be far off when a united and liberated Vietnam will celebrate its victory in a free Saigon (quoted in Flew 2001, 119).

So Russell expressed “full solidarity” with the Vietnamese Communist leader who was already at the time responsible for labor camps, reeducation, torture, and mass executions under the slogan “Better ten innocent deaths than one enemy survivor” (Courtois et al. 1999, 568–69; Rosefielde 2009, 110–11). Could Russell have known (or reasonably suspected) in 1966 the truth about Ho Chi Minh’s murderous past? Actually, yes. In From Colonialism to Communism: A Case History of North Vietnam, published in the United States in 1964, Hoang Van Chi estimated that around half a million people lost their lives due to Ho Chi Minh’s policies in the fifties. The book had an immediate impact and any responsible person making public statements about Vietnam should have known about it. Russell did not live to see his “great wish” come true; the Communist “liberation” of Vietnam led to hundreds of thousands deaths.

His anti-Americanism was so notorious that even W. V. Quine, who had a great deal of respect for Russell as a philosopher, once said: “I was never drawn to socialism and communism as [Russell] was, much less to the views he held in his declining years when he was demonstrating against the United States in favor of Soviet Russia” (quoted in Borradori 1994, 34). The New York Times published an amazingly biased letter from Russell about the Vietnam War in 1963, to which the editors appended a response saying the letter “reflects an unfortunate and—despite his eminence as a philosopher—an unthinking receptivity to the most transparent Communist propaganda.” The editors expressed their own serious reservations about U.S. policy in Vietnam but said that Russell’s letter represented “something beyond reasoned criticism” and in some parts amounted to “arrant nonsense.”

Russell had taken an anti-American stance earlier, during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. Here is his crucial argument from a leaflet released on October 23, 1962, reprinted in his autobiography (1967–69; 2009, 625):

YOU ARE TO DIE

Not in the course of nature, but within a few weeks, and not you alone, but your family, your friends, and all the inhabitants of Britain, together with many hundreds of millions of innocent people elsewhere.

WHY?

Because rich Americans dislike the Government that Cubans prefer, and have used part of their wealth to spread lies about it.

Monk makes an apt comment about the pamphlet: “Its oversimplification of the issues involved would have been startling had [it] come from a schoolboy; from one of the greatest thinkers of our age, [it was] truly astonishing” (Monk 2000, 442).

Communist Temptations at Oxford

J. L. Austin, one of the key figures in ordinary language philosophy (a school of thought that flourished at Oxford in the 1950s and 1960s), argued that philosophy has beneficial consequences in the political domain:

In Austin’s generation, the social and political implications of the teaching of philosophy, and of the forming of habits of thought in a ruling class, were certainly not unnoticed, and he was acutely conscious of them. He seriously wanted to ‘make people sensible’ and clear-headed, and immune to ill-founded and doctrinaire enthusiasms. He believed that philosophy, if it inculcated respect for ‘the facts’ and for accuracy, was one of the best instruments for this purpose (Hampshire 1992, 244).

Notice that the author of the text just quoted, Stuart Hampshire, who is also a well-known British philosopher, seems to agree with Austin and, furthermore, associates the belief about the political implications of the teaching of philosophy not just with Austin but more widely with “Austin’s generation.”

And yet Austin’s famously meticulous analysis and his sharp logical mind did not save him from “ill-founded enthusiasms.” For after visiting the Soviet Union in the mid-thirties he said that he “was impressed by his experience” and that he had “admiration for the great men who had worked against gigantic odds, Marx and Lenin for example” (Berlin 1973, 6). Being “impressed” with the Stalinism of the mid-thirties is not easily reconcilable with being “clear-headed.” On a different occasion Isaiah Berlin reports that Austin “came back from the Soviet Union deeply impressed by the discipline and the austerity of life and so forth, and remained under the influence for some time” (Hampshire & Berlin 1972, from 0:06). For many details about ordinary life under Stalinism in the thirties and how deeply unimpressive it was, see Sheila Fitzpatrick’s Ordinary Stalinism.4

Another example of the belief that philosophy can help the forces of reason comes from philosopher A. J. Ayer, who in his famous book Language, Truth, and Logic (1936, 35) claimed that the task of philosophy is to define rationality. But someone whose main task is to try to understand the nature of rationality should be the first one to spot irrationality and be on guard against it. Yet just a few months after the book was published Ayer had a baffling bout of irrationality in politics. Over one weekend in February 1937 Ayer was “wrestling with the choice” of whether to join the Communist Party of Great Britain (Rogers 1999, 136). It was a very strange moment to be considering this move. Just a few weeks earlier, thirteen Old Bolsheviks had been sentenced to death in a farcical Moscow show trial. The verdict had been openly celebrated by the British Communist Party.

Any reasonable person must have had serious doubts about the credibility of the accusations and the whole judicial procedure. The London Times reported on January 26, 1936:

The guilt of all the prisoners was already officially announced before the public proceedings began. . . . The Soviet Press is duly crying for death to the “wriggling hypocrites,” the “mischievous vermin,” the “venomous Trotskyist vipers.” . . . The whole process is loathsome. All that can be said of it is that guilt may sometimes be established, innocence never. . . . The general atmosphere can only be compared to the inquiries that were made into witchcraft in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when wretched old men and women were persuaded that they too had departed from the Absolute Good as laid down by authority and that their harmless or venal practices were the result of communing with the Evil One.

But despite all these worrying features and also the bizarre fact that the accused were very eager to confess and help the prosecutors make the case for their death penalty, the British Communist Party took the hard Stalinist line and—only a few days before Ayer’s “to join or not to join” moment—claimed in its newspaper the Daily Worker that “the scrupulous fairness of the trial, the overwhelming guilt of the accused, and the justness of the sentences is recognized” (Redman 1958, 48). Only several months earlier, at the end of another show trial in Moscow in which sixteen Old Bolsheviks were sentenced to death, the title of the editorial in the Party’s newspaper was “Shoot the reptiles!”

And this is the political party that Ayer was on the verge of joining. He decided not to only at the last moment. The funny thing is that apparently Ayer was not bothered much by the Party’s slavishly praising all aspects of Soviet totalitarianism; his reason for not joining was that he “did not believe in dialectical materialism” (Ayer 1977, 187). Apparently Ayer had no major disagreements with Stalin’s politics at the time—only with his philosophical opinions.

But why did Ayer want to join the Communist Party in the first place? According to his friend Philip Toynbee, it was just his “desire for reasonable activity” (ibid.). So relying on this report, we discover something interesting: A well-known philosopher who believed that philosophers can best explain the meaning of the word rational or reasonable regarded becoming a card-carrying member of an organization that fully supported Moscow’s policies during the Great Terror of the thirties to be a reasonable activity.

Bad Arguments and Bad Politics: What Causes What?

Michael Dummett, too, believed in the salutary influence of philosophy on political attitudes. Speaking about Gottlob Frege’s political views that he found so shocking (for more about Frege’s case, see pp. 188–192), Dummett said “Frege’s philosophy ought to have kept him from holding such views but it didn’t” (quoted in Warburton & Edmonds 2010). Here again is the idea that philosophy can (or should) protect people from bad political opinions. Also, according to Dummett, philosophers in particular “have a duty to make themselves sensitive to social issues” and to do something about them. “If you are an intellectual, and particularly if you aim to be a philosopher, and therefore to think about very general questions, then you ought to be capable of responding to general burning issues, whether the public is ignoring them or has fastened its attention upon them” (Dummett 1996, 194). But, as documented in chapter 9, it appears that Dummett’s philosophy didn’t keep him from making a fool of himself in politics, either.

Dagfinn Føllesdal, a philosopher who had a distinguished career at Harvard and Stanford, also stresses the political benefits of analytic philosophy:

We should engage in analytic philosophy not just because it is good philosophy, but also for reasons of individual and social ethics . . . In our philosophical writing and teaching we should emphasize the decisive role that must be played by argument and justification. This will make life more difficult for political leaders and fanatics who spread messages which do not stand up to critical scrutiny, but which nevertheless often have the capacity to seduce the masses into intolerance and violence. Rational argument and rational dialogue are of the utmost importance for a well-functioning democracy. To educate people in the activities is perhaps the most important task of analytic philosophy (1997, 15–16).

Despite his usual sensitivity to rational argument in philosophy, Føllesdal lowered his guard considerably when turning to politics, e.g. when he was bamboozled into allowing his name to be used in a political conflict in a foreign country, although he should have been aware that he was poorly informed about what was happening there (see p. 173).

Many more examples could be given of analytic philosophers who have argued that the critical ability supposedly cultivated by philosophical education is the best antidote to political follies and fanaticism. I happen to disagree with them. I have found no good evidence that being trained in analytic philosophy boosts political rationality. On the contrary, my aim in this book is to show that some of the leading analytic philosophers have held political views that are both deeply troubling and manifestly irrational. At the same time, in contrast to their highly problematic political beliefs and activity, their academic contributions to philosophy usually carried the marks of extremely careful thinking and the highest intellectual rigor.

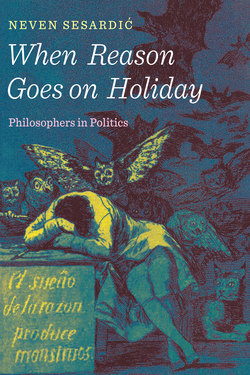

Wittgenstein famously said that “philosophical problems arise when language goes on holiday” (1967: I, §38). This book deals with another phenomenon: When philosophers enter politics it is often reason that goes on holiday.

In the text that follows I will drop the qualifier analytic when talking about philosophers, since virtually all of my examples will be analytic philosophers. The illustrations will include some of the greatest names of contemporary Anglo-American philosophy such as Neurath, Carnap, Wittgenstein, Putnam, Davidson, Dummett, Lakatos, Parfit, and many others, as well as Einstein, who, besides being a physicist, has been embraced by many philosophers as one of their own.

I will explore in detail the individual cases of these very distinguished philosophers and their highly dubious political views or actions. I will also briefly address the politicization of some leading philosophical institutions.

The bleak record will cast additional doubt on the hypothesis that reasoning skill in philosophical matters transfers to political judgment. Perhaps it is not the way philosophers argue that influences their politics but, rather, the opposite. Maybe it is philosophers’ politics that affects their intellectual standards (for the worse) and leads them down the path of irrationality when they enter the political domain.

1 They also cited the UNESCO publication Philosophy: A School of Freedom (2007), but far from advocating compulsory philosophy classes that book actually urges restraint and caution in this matter. It recommends that those who think about introducing philosophy into primary-school curricula should first initiate trial projects “so that the success of these practices can be evaluated in relation to national educational objectives” (17).

2 “In fact many interventions have been shown to raise test scores and mental ability ‘in the short run’ (i.e., while the program itself was in progress), but long-run gains have proved more elusive” (Neisser et al. 1996, 88).

3 As one of the participants of these events reported: “In England there was once a ‘Long Parliament.’ The Constituent Assembly of the RSFSR [Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic] was the shortest parliament in the entire history of the world. It ended its inglorious and joyless life after 12 hours and 40 minutes.” (www.marxists.org/history/ussr/government/red-army/1918/raskolnikov/ilyin/ch01.htm#bk04)

4 A good illustration is the following joke that was popular in the Soviet Union precisely in the thirties: There is a ring at the door at 3 o’clock at night. The husband goes to answer. He returns and says: “Don’t worry, dear, it is bandits who have come to rob us.”