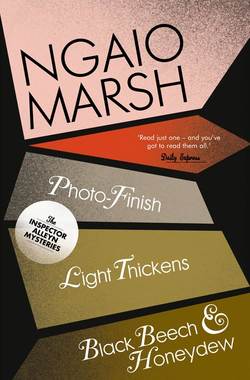

Читать книгу Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 11: Photo-Finish, Light Thickens, Black Beech and Honeydew - Ngaio Marsh, Stella Duffy - Страница 32

II

ОглавлениеAlleyn wondered if he was about to take the most dangerous decision of his investigative career. If he took this decision and failed, not only would he make an egregious ass of himself before the New Zealand police but he would effectively queer the pitch for their subsequent investigations and probably muck up any chance of an arrest. Or would he? In the event of failure, was there no chance of a new move, a strategy in reserve, a surprise attack? If there was, he was damned if he knew what it could be.

He went over the arguments again: The time factor. The riddle of the keys. The photograph. The conjectural motive. The appalling conclusion. He searched for possible alternatives to each of these and could find none.

He resurrected the dusty old bit of investigative folklore: If all explanations except one fail, then that one, however outrageous, will be the answer.

And, God knew, they were dealing with the outrageous.

So he made up his mind and having done that went downstairs and out into the watery sunshine for a breather.

All the guests had evidently been moved by the same impulse. They were abroad on the Island in pairs and singly. Whereas earlier in the morning Alleyn had likened those of them who had come out into the landscape to surrealistic details, now, while still wildly anachronistic, as was the house itself, in their primordial setting, they made him think of persons in a poem by Verlaine or perhaps by Edith Sitwell. Signor Lattienzo in his Tyrolean hat and his gleaming eyeglass, stylishly strolled beside Mr Ben Ruby who smoked a cigar and was rigged out for the country in a brand new Harris tweed suit. Rupert Bartholomew, wan in corduroy, his hair romantically disordered, his shoulders hunched, stood by the tumbled shore and stared over the lake. And was himself stared at, from a discreet distance, by the little Sylvia Parry with a scarlet handkerchief round her head. Even the stricken Miss Dancy had braved the elements. Wrapped up, scarfed and felt-hatted, she paced alone up and down a gravel path in front of the house as if it were the deck of a cruiser.

To her from indoors came Mr Reece in his custom-built outfit straight from pages headed ‘Rugged Elegance: For Him’ in the glossiest of periodicals. He wore a peaked cap which he raised ceremoniously to Miss Dancy, who immediately engaged him in conversation, clearly of an emotional kind. But he’s used to that, thought Alleyn, and noticed how Mr Reece balanced Miss Dancy’s elbow in his dogskin grasp as he squired her on her promenade.

He had thought they completed the number of persons in the landscape until he caught sight out of the corner of his eye, of some movement near one of the great trees near the lake. Ned Hanley was standing there. He wore a dark green coat and sweater and merged with his background. He seemed to survey the other figures in the picture.

One thing they all had in common and that was a tendency to halt and stare across the lake or shade their eyes, tip back their heads and look eastward into the fast-thinning clouds. He had been doing this himself.

Mr Ben Ruby spied him, waved his cigar energetically and made towards him. Alleyn advanced and at close quarters found Mr Ruby looking the worse for wear and self-conscious.

‘’Morning, old man,’ said Mr Ruby. ‘Glad to see you. Brightening up, isn’t it? Won’t be long now. We hope.’

‘We do indeed.’

‘You hope, anyway, I don’t mind betting. Don’t envy you your job. Responsibility without the proper backing, eh?’

‘Something like that,’ said Alleyn.

‘I owe you an apology, old man. Last evening. I’d had one or two drinks. You know that?’

‘Well …’

‘What with one thing and another – the shock and that. I was all to pieces. Know what I mean?’

‘Of course.’

‘All the same – bad show. Very bad show,’ said Mr Ruby, shaking his head and then wincing.

‘Don’t give it another thought.’

‘Christ, I feel awful,’ confided Mr Ruby and threw away his cigar. ‘It was good brandy, too. The best. Special cognac. Wonder if this guy Marco could rustle up a corpse-reviver.’

‘I dare say. Or Hanley might.’

Mr Ruby made the sound that is usually written: ‘T’ss’ and after a brief pause said in a deep voice and with enormous expression: ‘Bella! Bella Sommita! You can’t credit it, can you? The most beautiful woman with the most gorgeous voice God ever put breath into. Gone! And how! And what the hell we’re going to do about the funeral’s nobody’s business. I don’t know of any relatives. It’d be thoroughly in character if she’s left detailed instructions and bloody awkward ones at that. Pardon me, it slipped out. But it might mean cold storage to anywhere she fancied or ashes in the Adriatic.’ He caught himself up and gave Alleyn a hard if bloodshot stare. ‘I suppose it’s out of order to ask if you’ve formed an idea?’

‘It is, really. At this stage,’ Alleyn said. ‘We must wait for the police.’

‘Yeah? Well, here’s hoping they know their stuff.’ He reverted to his elegiac mood. ‘Bella!’ he apostrophized. ‘After all these years of taking the rough with the smooth, if you can understand me. Hell, it hurts!’

‘How long an association has it been?’

‘You don’t measure grief by months and years,’ Mr Ruby said reproachfully. ‘How long? Let me see? It was on her first tour of Aussie. That would be in ’72. Under the Bel Canto management in association with my firm – Ben Ruby Associates. There was a disagreement with Bel Canto and we took over.’

Here Mr Ruby embarked on a long parenthesis explaining that he was a self-made man, a Sydneysider who had pulled himself up by his own boot-strings and was proud of it and how the Sommita had understood this and had herself evolved from peasant stock.

‘And,’ said Alleyn when an opportunity presented itself, ‘a close personal friendship had developed with the business association?’

‘This is right, old man. I reckon I understood her as well as anybody ever could. There was the famous temperament, mind, and it was a snorter while it lasted but it never lasted long. She always sends – sent – for Maria to massage her shoulders and that would do the trick. Back into the honied-kindness bit and everybody loving everybody.’

‘Mr Ruby, have you anything to tell me that might, in however far-fetched or remote a degree, help to throw light on this tragedy?’

Mr Ruby opened his arms wide and let them fall in the classic gesture of defeat.

‘Nothing?’ Alleyn said.

‘This is what I’ve been asking myself ever since I woke up. When I got round, that is, to asking myself anything other than why the hell I had to down those cognacs.’

‘And how do you answer yourself?’

Again the gesture. ‘I don’t,’ Mr Ruby confessed. ‘I can’t. Except –’ He stopped, provokingly, and stared at Signor Lattienzo who by now had arrived at the lakeside and contemplated the water rather, in his Tyrolean outfit, like some poet of the post-Romantic era.

‘Except?’ Alleyn prompted.

‘Look!’ Mr Ruby invited. ‘Look at what’s been done and how it’s been done. Look at that. If you had to say – you, with your experience – what it reminded you of, what would it be? Come on.’

‘Grand opera,’ Alleyn said promptly.

Mr Ruby let out a strangulated yelp and clapped him heavily on the back. ‘Good on you!’ he cried. ‘Got it in one! Good on you, mate. And the Italian sort of grand opera, what’s more. That funny business with the dagger and the picture! Verdi would have loved it. Particularly the picture. Can you see any of us, supposing he was a murderer, doing it that way? That poor kid Rupert? Ned Hanley, never mind if he’s one of those? Monty? Me? You? Even if you’d draw the line at the props and the business. “No” you’d say “No”. Not that way. It’s not in character, it’s impossible, it’s not – it’s not –’ and Mr Ruby appeared to hunt excitedly for the mot juste of his argument. ‘It’s not British,’ he finally pronounced, and added: ‘Using the word in its widest sense. I’m a Commonwealth man myself.’

Alleyn had to give himself a moment or two before he was able to respond to this declaration.

‘What you are saying,’ he ventured, ‘in effect, is that the murderer must be one of the Italians on the premises. Is that right?’

‘That,’ said Mr Ruby, ‘is dead right.’

‘It narrows down the field of suspects,’ said Alleyn drily.

‘It certainly does,’ Mr Ruby portentously agreed.

‘Marco and Maria?’

‘Right.’

During an uncomfortable pause Mr Ruby’s rather bleary regard dwelt upon Signor Lattienzo in his windblown cape by the lakeside.

‘And Signor Lattienzo, I suppose?’ Alleyn suggested.

There was no reply.

‘Have you,’ Alleyn asked, ‘any reason, apart from the grand opera theory, to suspect one of these three?’

Mr Ruby seemed to be much discomforted by this question. He edged with his toe at a grassy turf. He cleared his throat and looked aggrieved.

‘I knew you’d ask that,’ he said resentfully.

‘It was natural, don’t you think, that I should?’

‘I suppose so. Oh yes. Too right it was. But listen. It’s a terrible thing to accuse anyone of. I know that. I wouldn’t want to say anything that’d unduly influence you. You know. Cause you to – to jump to conclusions or give you the wrong impression. I wouldn’t like to do that.’

‘I don’t think it’s very likely.’

‘No? You’d say that, of course. But I reckon you’ve done it already. I reckon like everyone else you’ve taken the old retainer stuff for real.’

‘Are you thinking of Maria?’

‘Too bloody right I am, mate.’

‘Come on,’ Alleyn said. ‘Get it off your chest. I won’t make too much of it. Wasn’t Maria as devoted as one was led to suppose?’

‘Like hell she was! Well, that’s not correct either. She was devoted all right but it was a flaming uncomfortable sort of devotion. Kind of dog-with-a-bone affair. Sometimes when they’d had a difference you’d have said it was more like hate. Jealous! She’s eaten up with it. And when Bella was into some new “friendship” – know what I mean? – Maria as likely as not would turn plug-ugly. She was even jealous in a weird sort of way, of the artistic triumphs. Or that’s the way it looked to me.’

‘How did she take the friendship with Mr Reece?’

‘Monty?’ A marked change came over Mr Ruby. He glanced quickly at Alleyn as if he wondered whether he was unenlightened in some respect. He hesitated and then said quietly: ‘That’s different again, isn’t it?’

‘Is it? How, “different”?’

‘Well – you know.’

‘But I don’t know.’

‘It’s platonic. Couldn’t be anything else.’

‘I see.’

‘Poor old Monty. Result of an illness. Cruel thing, really.’

‘Indeed? So Maria had no cause to resent him.’

‘This is right. She admires him. They do, you know. Italians. Especially his class. They admire success and prestige more than anything else. It was a very different story when young Rupert came along. Maria didn’t worry about letting everyone see what she felt about that lot. I’d take long odds she’ll be telling you the kid done – did – it. That vindictive, she is. Fair go – I wouldn’t put it past her. Now.’

Alleyn considered for a moment or two. Signor Lattienzo had now joined Rupert Bartholomew on the lakeside and was talking energetically and clapping him on the shoulder. Mr Reece and Miss Dancy still paced their imaginary promenade deck and the little Sylvia Parry, perched dejectedly on a rustic seat, watched Rupert.

Alleyn said: ‘Was Madame Sommita tolerant of these outbursts from Maria?’

‘I suppose she must have been in her own way. There were terrible scenes, of course. That was to be expected, wasn’t it? Bella’d threaten Maria with the sack and Maria’d throw a fit of hysterics and then they’d both go weepy on it and we’d be back to square one with Maria standing behind Bella massaging her shoulders and swearing eternal devotion. Italians! My oath! But it was different, totally different – with the kid. I’d never seen her as far gone over anyone else as she was with him. Crazy about him. In at the deep end, boots and all. That’s why she took it so badly when he saw the light about that little opera of his and wanted to opt out. He was dead right, of course, but Bella hadn’t got any real musical judgement. Not really. You ask Beppo.’

‘What about Mr Reece?’

‘Tone deaf,’ said Mr Ruby.

‘Really?’

‘Fact. Doesn’t pretend to be anything else. He was annoyed with the boy for disappointing her, of course. As far as Monty was concerned the diva had said the opus was great, and what she said had got to be right. And then of course he didn’t like the idea of throwing a disaster of a party. In a way,’ said Mr Ruby, ‘it was the Citizen Kane situation with the boot on the other foot. Sort of.’ He waited for a moment and then said: ‘I feel bloody sorry for that kid.’

‘God knows, so do I,’ said Alleyn.

‘But he’s young. He’ll get over it. All the same, she’d a hell of a lot to answer for.’

‘Tell me. You knew her as well as anybody, didn’t you? Does the name “Rossi” ring a bell?’

‘Rossi,’ Mr Ruby mused. ‘Rossi, eh? Hang on. Wait a sec.’

As if to prompt, or perhaps warn him, raucous hoots sounded from the jetty across the water, giving the intervals without the cadence of the familiar singing-off phrase ‘Dah dahdy dah-dah. Dah dah.’

Les appeared on deck and could be seen to wave his scarlet cap.

The response from the islanders was instant. They hurried into a group. Miss Dancy flourished her woollen scarf. Mr Reece raised his arm in a Roman salute. Signor Lattienzo lifted his Tyrolean hat high above his head. Sylvia ran to Rupert and took his arm. Hanley moved out of cover and Troy, Mrs Bacon and Dr Carmichael came out of the house and pointed Les out to each other from the steps. Mr Ruby bawled out, ‘He’s done it. Good on ’im, ’e’s done it.’

Alleyn took a handkerchief from his breast pocket and a spare from his overcoat. He went down to the lake edge and semaphored: Nice Work. Les returned to the wheelhouse and sent a short toot of acknowledgement.

The islanders chattered excitedly, telling each other that the signal must mean the launch was mobile again, that the lake was undoubtedly calmer and that when the police did arrive they would be able to cross. The hope that they themselves would all be able to leave remained unspoken.

They trooped up to the house and were shepherded in by Mr Reece who said, with sombre playfulness, that ‘elevenses’ were now served in the library.

Troy and Dr Carmichael joined Alleyn. They seemed to be in good spirits. ‘We’ve finished our chores,’ Troy said, ‘and we’ve got something to report. Let’s have a quick swallow, and join up in the studio.’

‘Don’t make it too obvious,’ said Alleyn, who was aware that he was now under close though furtive observation by most of the household. He fetched two blameless tomato juices for himself and Troy. They joined Rupert and Sylvia Parry who were standing a little apart from the others and were not looking at each other. Rupert was still white about the gills but, or so Alleyn thought, rather less distraught – indeed there was perhaps a hint of portentousness, of self-conscious gloom in his manner.

She has provided him with an audience, thought Alleyn. Let’s hope she knows what she’s letting herself in for.

Rupert said: ‘I’ve told Sylvia about – last night.’

‘So I supposed,’ said Alleyn.

‘She thinks I was right.’

‘Good.’

Sylvia said: ‘I think it took wonderful courage and artistic integrity and I do think it was right.’

‘That’s a very proper conclusion.’

‘It won’t be long now, will it?’ Rupert asked. ‘Before the police come?’ He pitched his voice rather high and brittle with the sort of false airiness some actors employ when they hope to convey suppressed emotion.

‘Probably not,’ said Alleyn.

‘Of course, I’ll be the prime suspect,’ Rupert announced.

‘Rupert, no,’ Sylvia whispered.

‘My dear girl, it sticks out a mile. After my curtain performance. Motive. Opportunity. The lot. We might as well face it.’

‘We might as well not make public announcements about it,’ Troy observed.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Rupert grandly. ‘No doubt I’m being silly.’

‘Well,’ Alleyn cheerfully remarked, ‘you said it. We didn’t. Troy, hadn’t we better sort out those drawings of yours?’

‘OK. Let’s. I’d forgotten.’

‘She leaves them unfixed and tiles the floor with them,’ Alleyn explained. ‘Our cat sat on a preliminary sketch of the Prime Minister and turned it into a jungle flower. Come on, darling.’

They found Dr Carmichael already in the studio. ‘I didn’t want Reece’s “elevenses”,’ he said. And to Troy: ‘Have you told him?’

‘I waited for you,’ said Troy.

They were, Alleyn thought, as pleased as Punch with themselves. ‘You tell him,’ they said simultaneously. ‘Ladies first,’ said the doctor.

‘Come on,’ said Alleyn.

Troy inserted her thin hand in a gingerly fashion into a large pocket of her dress. Using only her first finger and her thumb she drew out something wrapped in one of Alleyn’s handkerchiefs. She was in the habit of using them as she preferred a large one and she had been known when intent on her work to confuse the handkerchief and her paint-rag, with regrettable results to the handkerchief and to her face.

She carried her trophy to the paint-table and placed it there. Then, with a sidelong look at her husband, she produced two clean hog-hair brushes and, using them upside down in the manner of chopsticks, fiddled open the handkerchief and stood back.

Alleyn walked over, put his arm across her shoulders and looked at what she had revealed.

A large heavy envelope, creased and burnt but not so extensively that an airmail stamp and part of the address was not still in evidence. The address was typewritten.

The Edit

The Watchma

PO Bo

NSW 14C

SY

Australia

‘Of course,’ Troy said after a considerable pause, ‘it may be of no consequence at all, may it?’

‘Suppose we have the full story?’

‘Yes. All right. Here goes, then.’

Their story was that they had gone some way with their housemaiding expedition when Troy decided to equip herself with a box-broom and a duster. They went downstairs in search of them and ran into Mrs Bacon emerging from the study. She intimated that she was nearing the end of her tether. The staff, having gone through progressive stages of hysteria and suspicion, had settled for a sort of work-to-rule attitude and, with the exception of the chef who had agreed to provide a very basic luncheon and Marco who was, said Mrs Bacon, abnormally quiet but did his jobs, either sulked in their rooms or muttered together in the staff sitting room. As far as Mrs Bacon could make out, the New Zealand ex-hotel group suspected in turn Signor Lattienzo, Marco and Maria on the score of their being Italians and Mr Reece whom they cast in the role of de facto cuckold. Rupert Bartholomew was fancied as an outside chance on the score of his having turned against the Sommita. Maria had gone to earth, supposedly in her room. Chaos, Mrs Bacon said, prevailed.

Mrs Bacon herself had rushed round the dining and drawing rooms while Marco set out the elevenses. She had then turned her attention to the study and found to her horror that the open fireplace had not been cleaned nor the fire relaid. To confirm this, she had drawn their attention to a steel ashpan she herself carried in her rubber-gloved hands.

‘And that’s when I saw it, Rory,’ Troy explained. ‘It was sticking up out of the ashes and I saw what’s left of the address.’

‘And she nudged me,’ said Dr Carmichael proudly, ‘and I saw it too.’

‘And he behaved perfectly,’ Troy intervened. ‘He said: “Do let me take that thing and tell me where to empty it.” And Mrs Bacon said, rather wildly: “In the bin. In the yard,” and made feeble protestations and at that moment we all heard the launch hooting and she became distracted. So Dr Carmichael got hold of the ashpan. And I – well – I – got hold of the envelope and put it in my pocket among your handkerchief which happened to be there.’

‘So it appears,’ Dr Carmichael summed up, ‘that somebody typed a communication of some sort to The Watchman and stamped the envelope which he or somebody else then chucked on the study fire and it dropped through the grate into the ashpan when it was only half-burnt. Or doesn’t it?’

‘Did you get a chance to have a good look at the ashes?’ asked Alleyn.

‘Pretty good. In the yard. They were faintly warm. I ran them carefully into a zinc rubbish bin already half-full. There were one or two very small fragments of heavily charred paper and some clinkers. Nothing else. I heard someone coming and cleared out. I put the ashpan back under the study grate.’

Alleyn bent over the trophy. ‘It’s a Sommita envelope,’ said Troy. ‘Isn’t it?’

‘Yes. Bigger than the Reece envelope but the same paper: like the letter she wrote to the Yard.’

‘Why would she write to The Watchman?’

‘We don’t know that she did.’

‘Don’t we?’

‘Or if she did, whether her letter was in this envelope.’ He took one of Troy’s brushes and used it to flip the envelope over. ‘It may have been stuck up,’ he said, ‘and opened before the gum dried. There’s not enough left to be certain. It’s big enough to take the photograph.’

Dr Carmichael blew out his cheeks and then expelled the air rather noisily. ‘That’s a long shot, isn’t it?’ he said.

‘Of course it is,’ agreed Alleyn. ‘Pure speculation.’

‘If she wrote it,’ Troy said carefully, ‘she dictated it. I’m sure she couldn’t type, aren’t you?’

‘I think it’s most unlikely. The first part of her letter to the Yard was impeccably typed and the massive postscript flamboyantly handwritten. Which suggested that she dictated the beginning or told young Rupert to concoct something she could sign, found it too moderate and added the rest herself.’

‘But why,’ Dr Carmichael mused, ‘was this thing in the study, on Reece’s desk? I know! She asked that secretary of his to type it because she’d fallen out with young Bartholomew. How’s that?’

‘Not too bad,’ said Alleyn. ‘Possible. And where, do you suggest, is the letter? It wasn’t in the envelope. And, by the way, the envelope was not visible on Reece’s desk when you and I, Carmichael, visited him last night.’

‘Really? How d’you know?’

‘Oh, my dear chap, the cop’s habit of using the beady eye, I suppose. It might have been there under some odds and ends in his “out” basket.’

Troy said: ‘Rory, I think I know where you’re heading.’

‘Do you, my love? Where?’

‘Could Marco have slid into the study to put the photograph in the postbag before Hanley had emptied the mailbox into it and could he have seen the typed and addressed envelope on the desk and thought there was a marvellous opportunity to send the photograph to The Watchman, because nobody would question it. And so he took out her letter or whatever it was and chucked it on the fire and put the photograph in the envelope and –’

Troy, who had been going great guns, brought up short. ‘Blast!’ she said.

‘Why didn’t he put it in the postbag?’ asked Alleyn.

‘Yes.’

‘Because,’ Dr Carmichael staunchly declared, ‘he was interrupted and had to get rid of it quick. I think that’s a damn good piece of reasoning, Mrs Alleyn.’

‘Perhaps,’ Troy said, ‘her letter had been left out awaiting the writer’s signature and – no, that’s no good.’

‘It’s a lot of good,’ Alleyn said warmly. ‘You have turned up trumps, you two. Damn Marco. Why can’t he make up his dirty little mind that his best move is to cut his losses and come clean. I’ll have to try my luck with Hanley. Tricky.’

He went out on the landing. Bert had resumed his guard duty and lounged back in the armchair reading a week-old sports tabloid. A homemade cigarette hung from his lower lip. He gave Alleyn the predictable sideways tip of his head.

Alleyn said: ‘I really oughtn’t to impose on you any longer, Bert. After all, we’ve got the full complement of keys now and nobody’s going to force the lock with the amount of traffic flowing through this house.’

‘I’m not fussy,’ said Bert which Alleyn took to mean that he had no objections to continuing his vigil.

‘Well, if you’re sure,’ he said.

‘She’ll be right.’

‘Thank you.’

The sound of voices indicated the emergence of the elevenses party. Miss Dancy, Sylvia Parry and Rupert Bartholomew came upstairs. Rupert, with an incredulous look at Bert and a scary one at Alleyn, made off in the direction of his room. The ladies crossed the landing quickly and ascended the next flight. Mr Reece, Ben Ruby and Signor Lattienzo made for the study. Alleyn ran quickly downstairs in time to catch Hanley emerging from the morning room.

‘Sorry to bother you,’ he said, ‘but I wonder if I might have a word. It won’t take a minute.’

‘But of course,’ said Hanley. ‘Where shall we go? Back into the library?’

‘Right.’

When they were there Hanley winningly urged further refreshment. Upon Alleyn’s declining, he said: ‘Well, I will; just a teeny tiddler,’ and helped himself to a gin-and-tonic. ‘What can I do for you, Mr Alleyn?’ he said. ‘Is there any further development?’

Alleyn said: ‘Did you type a letter to The Watchman some time before Madame Sommita’s death?’

Hanley’s jaw dropped and the hand holding his drink stopped half-way to his mouth. For perhaps three seconds he maintained this position and then spoke.

‘Oh Christmas!’ he said. ‘I’d forgotten. You wouldn’t credit it, would you? I’d entirely forgotten.’

He made no bones about explaining himself and did so very fluently and quite without hesitation. He had indeed typed a letter from the Sommita to The Watchman