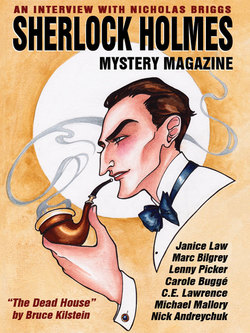

Читать книгу Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #7 - Nicholas Briggs - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTERVIEW WiTH C. E. LAWRENCE

The Darker Half of Carole Buggé

Conducted by (Mrs) Martha Hudson

I regret that for the past two issues, I have been unavailable to write my customary contributions to Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, but thanks to the wonders of modern communications, I have managed to interview another of this magazine’s frequent contributors, Miss Carole Buggé. (Forgive me for eschewing the use of ‘Ms,” which strikes me as an unharmonious neologism.)

Dr Watson, I may say, is quite taken with Carole. After reading her shorter fiction, as well as what I understand are called her three “cosy” Berkley Books mystery novels, Who Killed Blanche Dubois?, Who Killed Dorian Gray?, and Who Killed Mona Lisa?, the good doctor permitted her access to his notebooks; as a result she has given us two new Sherlock Holmes novels, The Star of India and The Haunting of Torre Abbey, as well as quite a few shorter Holmesian adventures.

It is rather an open secret, however, that for the past several years, she has taken to writing much darker mysteries, the “Silent” series y clept, under the pen name of C E Lawrence: Silent Screams, Silent Victim, and the most recent, Silent Kills. All of them feature a deeply troubled New York City forensic profiler named Lee Campbell, and in each he must track down truly frightening serial killers.

Below is a transcript of our conversation about her new persona. For convenience, my questions are prefaced by H for Hudson, whereas Carole’s replies are designated CE.

* * * *

H: What does the C. E. stand for, may I ask?

CE: Carole Elizabeth. Lawrence is a family name.

H: What prompted you to begin a series of books about serial killers?

CE: I’ve always been interested in hidden behavior, in people’s dark sides, perhaps in part because in my family no one was supposed to have a dark side; these things were never talked about, so that made me even more curious about it. Also, I think most writers have a natural interest in psychology, in human behavior, and what can be more intriguing to a writer than extreme behavior? And it seems to me that serial killers are about as extreme as it gets.

H: Is that why you write chapters from the killer’s perspective?

CE: Yes. I think it would be very challenging but almost impossible to write a book in which the killer is the protagonist. It was done in American Psycho, of course, but not entirely successfully, I think. So I knew the killer couldn’t be the hero, but I wanted to explore his mind in some way, so I came up with idea of having very short chapters from his point of view. I’m not sure if I succeeded, but I wanted to try to get inside the murderer, in Chesterton’s famous phrase.

H: Why create a protagonist who suffers from depression? Weren’t you afraid that might turn some readers away?

CE: I was actually given advice early on that I should stay away from having a damaged hero, that readers would want a kind of super-hero detective, but in reality I believe that damaged heroes are the only interesting kind (a lot of so-called super-heroes are damaged, after all: Superman is an orphan and an alien on a strange planet, and Batman is a weirdo with a bat fetish). Also, we’re all damaged by the time we reach adulthood, some more than others, of course, but I feel that suffering and loss are two of life’s constants, and that depression is a very real and understandable reaction to the shock of living, what Shakespeare so memorably called life’s slings and arrows. And I think a lot more people suffer or have suffered from various degrees of depression than we probably realize. And, of course, when I wrote the book I had recently been through my own bout of clinical depression.

H: What kind of research did you do for this book?

CE: I have a huge library of forensic books of all kinds, from Dead Men Do Tell Tales by Michael Baden to Forensics of Fingerprints Analysis. I spent a lot of nights reading and taking notes and, of course, there are some wonderful shows on television, especially Forensic Files, which I watch religiously. You can get all kinds of plot ideas from those shows, which are about real crimes and real people. I’ve been studying forensic psychology for some time through books, and I also took a graduate course at John Jay College for Criminal Justice, taught by Dr. Lewis Schlesinger. He was kind enough to let me audit the class, which was excellent, and also gave me his very informative and scholarly textbook, Sexual Homicide, which was one of the textbooks for that class. Interestingly, most of the students were women and I found it interesting that they often sat there calmly eating their lunch as we passed around horrific crime scene photographs. The men in the class seemed more disturbed by it than the women did. The research I did for this book was nowhere near as challenging as the research I did for my physics play Strings (for about a year I read physics books nonstop. It was really fun, but after a while, my head was spinning with quarks and muons and neutrinos)!

H: What was the most difficult thing about writing this book?

CE: Plot. Plot, plot, plot . . . did I mention plotting? Or, as Robert McKee would say, story. It was for this book and every other book I’ve ever written. I think any writer who claims that plots come easily to him/her is either a liar or a fool. It’s a bitch and a struggle and that saying about characters writing their own stories is pure nonsense. Oh, you can get away with that in a short story, sure, where you have only one event and one through line. But in a novel, where there are plots and subplots and multiple characters and 400 plus pages to fill with twists and surprises, you bloody well better put your plotting hat on and keep it on until your forehead bleeds, or you’re not doing your job. You have to keep coming up with ways to thicken the plot and twist it and turn the story and make it unexpected without making it feel contrived . . . that is never pretty and it’s never, ever easy. You know the genre of movie where the hero has cornered the villain in a warehouse, and there are all these barrels around and the bad guy picks one up and throws it at the hero, and he ducks, and the villain throws another one and he jumps over it, and so on? Well, you have to keep throwing barrels at your hero. And then you have to find new ways for him to jump out of the way. Your arms get really tired, and your brain starts to hurt, and you really want to stop, but you have to keep throwing those barrels. You have to make choices that seem original and surprising and yet entirely in keeping with the logic of the story. I care a lot about writing style, and graceful prose, but all the pretty writing in the world won’t hide a soft spot in your story.

H: Did you have any “Aha!” moments while working on this particular plot?

CE: Funny you should ask. I did, as a matter of fact. I had two such moments. The first one was after my agent had received a few rejections of the book, and I was getting a sense that though people liked the characters, they weren’t sucked in enough by the story. I didn’t know how to make it work, but I wasn’t ready to give up. At the time I was a summer resident of Byrdcliffe Arts Colony at the time, which is a lovely, idyllic spread of cabins in the woods on a mountainside overlooking Woodstock, New York. They have a kick ass library system in Ulster and Dutchess County, and so I took out The DaVinci Code on tape from the Woodstock Library. I had no television, no cable, no VCR, only my tinny little radio and my books on tape. It was, in many ways, the perfect life. I would listen to The DaVinci Code while I worked out every night in my cabin. I’m not sure the exact moment it hit me, but it gradually became clear to me there was a powerful lesson to be learned from that book: one thing Dan Brown does so well in it is to keep the pressure up at all times. There is a constant sense of danger and peril to the protagonist, from the first page to the end. I realized that’s what was missing from my book, and that there were flaccid scenes and chapters where people sat around comfortably talking philosophy or psychology or whatever. So I took out my cutting knife and whole chapters flew out the window. And I added a stabbing, a shooting, a car chase, a hanging, a beating, and in general just ratcheted up the tension more. And then we sold the book.

H: You said you had two such moments. What was the other one?

CE: That was a real classic “Aha!” moment. It was that same summer at Byrdcliffe, and I had just started out on a jog from my cabin on a beautiful evening in mid-July. I was jogging down Byrdcliffe Road when it hit me all of a sudden: I realized what the book needed was a major twist at the end, and I knew at that moment what the twist had to be. I had been working on this book for two years now, and I hadn’t seen it until that very moment. I remember the exact spot on Byrdcliffe Road where I was when it came to me, literally like a bolt out of the blue. But at the same time I realized that it was as though I had set the twist up all along; I really didn’t have to change anything in the rest of the book. It was as if my unconscious mind had been setting it up the whole time; once I saw it, it seemed not only logical but actually inevitable. And yet it was invisible to me until that moment. As Geoffrey Rush says in Shakespeare in Love, “It’s a mystery.”

H: Why do you think that is?

CE: Well, my mind was relaxed. The very act of running always jolts something loose in my brain. I would get my best ideas while jogging or mountain climbing or riding my bike up there. Of course, I was engaged all day long in struggling with the problems of writing the book, so my brain was primed, as it were, to come up with solutions, but I was always struck by how those solutions would present themselves at the most unexpected time. In this case, I didn’t even know I was looking for a big twist at the end until it popped into my head. But the minute it did, there was no question about it: I recognized the rightness of it.

H: How do you balance being a novelist and playwright? Is it hard moving back and forth?

CE: Actually, I find it refreshing. I feel like some stories are just begging to be plays, while others really need the pages of a novel in order to be properly explored. And then others strike me as screenplays. For instance, I just finished a screenplay about magicians. The title is The Assistant.

H: Doesn’t each form have its own challenges?

CE: Absolutely. Transition in a screenplay is a whole different technique than transition in a novel, or even a play. But I find it stimulating to move between the different forms. In a novel you have so much space, you can gas on about this and that (within reason, of course), whereas a screenplay is like an epic poem—so condensed, so streamlined. It’s story in its most essential form. And you have to think visually, which is great discipline for someone like me. I think one of the greatest dangers to a writer, by definition someone who loves language, is to be drunk with words. Danger, Will Robinson! That can lead to undisciplined, flaccid writing. Screenplay forces you out of that quickly; you’re always looking how to condense, condense, condense. And when you’re writing a play you have to show everything through dialogue and character interaction. I think it helps you to write better scenes when you’re working in prose fiction. You try to make your dialogue character-specific and pithy, just as you would in writing a play.

H: You write music, too, isn’t that right?

CE: Yes. I was trained as a classical pianist and singer, and Anthony Moore, my boyfriend at the time, was a composer. (His great uncle was Douglas Moore, the opera composer). Tony had a show done at Yale School of Drama, and he taught me how to do music manuscript so I could help him transcribe songs. One day about a year later I decided to write a musical, a kind of Faustian tale, and I just sat down at my piano and wrote a song. I called him out at his house in Cutchogue and played it for him over the phone. There was this long silence and I thought he hated it, but then he said, “That’s really good. It’s really interesting.” And I knew it was something I could do. I grew up playing the Great Composers, Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, etc., so it never occurred to me until then that was something I could do. I thought they lived on a whole other plane of existence—which was only reinforced by my classical training. I never studied theory or anything like that, but when Tony said he liked my song, I knew it was something I could do. He is a very gifted composer, so I trusted his judgment. And the only thing I enjoy more than writing is writing music. It is an amazingly joyous and completely engaging, sensual thing to do. I’ve written four complete musicals and am working on a new one, 31 Bond Street, about a real life murder that took place in the 19th century on Bond Street in New York. It was the O.J. Simpson of its time: a media circus, and was referred to as The Crime of the Century. Jack Finney has written a very good nonfiction book about it called Forgotten News: The Crime of the Century and Other Lost Stories.

H: You mentioned Shakespeare a few times. Is there anything special you would like to say about him?

CE: Oh, well, you know, he’s the Big Kahuna, isn’t he? What can you say . . . the man wrote the most exquisite poetry, dealt with The Big Questions in a way rarely equaled. My only consolation is that he wrote some real stinkers. The Merry Wives of Windsor is a wretched, boring play. Thank god.

H: Are there any questions or topics about you, your book, and your life that you would wish to stay away from?

CE: No, my life is an open book. Ha.