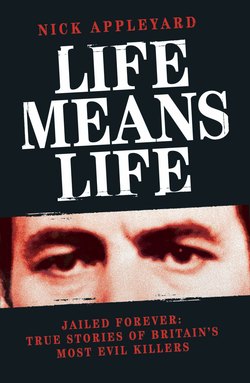

Читать книгу Life Means Life - Nick Appleyard - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеWhile anyone convicted of murder in the UK is automatically handed a life sentence, for only a tiny fraction does life really mean life. This grisly elite includes Dennis Nilsen, who butchered a string of young men in London, Rose West who – with her husband Fred – raped, tortured and murdered girls and women in the Gloucester area, and Ian Brady, one half of the Moors Murderers.

The crimes involved are of unparalleled savagery, perversion or scale. For these killers there is no hope of rehabilitation for society has ruled they must never walk the streets again. They are the men – and one woman – who committed the crimes that shocked and outraged Britain, and the courts have ruled they must end their days behind prison bars. In their wake, they leave a trail of death and devastation that both fascinates and revolts the world. Their trials have uncovered stories that horror writers would discard as outlandish; fascination for them is so enduring that every scrap of gossip about their life behind bars is devoured by the public, even decades after they were caged.

Crimes of this magnitude inevitably spark debate over the restoration of the death penalty. Within living memory every killer featured in this book would have gone to the gallows. In 1861 the Offences Against the Person Act dictated that anyone who murdered a fellow human must be executed, and so it was that all convicted murderers died, by hanging, for almost a century.

After many years, campaigners for the abolition of the death penalty secured a partial victory with the 1957 Homicide Act, which restricted capital punishment to cases of the five worst types of murder. They were, in the words of the Act: ‘Murder in the course or furtherance of theft, murder by shooting or causing an explosion, murder while resisting arrest or during an escape, murder of a police officer or prison officer and two or more murders – of any type – committed on different occasions’. Killers who did not meet the new criteria for hanging were given mandatory life prison sentences. This substitute sentence did not mean a lifelong period of imprisonment. Rather, it meant the prisoner would spend a finite period in jail before being released when he or she was no longer deemed a danger to others.

The 1957 Act received as much criticism as it did support. After all, why should someone who shoots a man dead be eligible for execution, while another who intentionally kills by strangulation or with a knife is not? Also, murder in the course of theft was punishable by hanging, while murder in the course of rape merely carried a jail sentence. In many ways, the new death penalty guidelines were as unfair as before.

Eight years later, the 1965 Murder (Abolition of the Death Penalty) Act replaced capital punishment with a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment. The last executions in Britain were Anthony Allen, 21, and Gwynne Owen Evans, 24, who were hanged respectively in Walton Prison, Liverpool, and Strangeways Prison, Manchester, on 13 August 1964. They had murdered a man while robbing him in his home on 7 April of the same year.

For almost two decades the basic rules of sentencing for murder in Britain went unchanged until 1983 when the ‘tariff system’ was introduced. The new rules allowed Home Secretaries to set the minimum terms that convicted killers would serve before being eligible for parole on life licence. The arrival of the new system brought with it the ‘whole life tariff’, a sentence reserved for those who commit the most heinous of crimes. Successive Home Secretaries used this power to increase the sentences of several high-profile murderers, many of whom feature in this book.

In November 2002, new human rights legislation and a Law Lords ruling stripped Labour Home Secretary David Blunkett of the power to set tariffs. Lord Bingham said the power exercised by the Home Secretary to decide the length of sentences was ‘incompatible’ with Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights – the right of a convicted person to have a sentence imposed by an independent and impartial tribunal. The minimum length of a life sentence is now set by the trial judge although the Attorney General can still appeal to the High Court if he considers a sentence unduly lenient and the Lord Chief Justice then has the power to increase that sentence.

In response to being stripped of the power to keep killers behind bars, Blunkett outlined new minimum terms to be used by sentencing judges. All convicted murderers are now sentenced to ‘life’ in prison but judges set their tariffs. ‘Starting points’ of 15 and 30 years are available to trial judges, depending on the severity of the crime. These tariffs can be lowered by ‘mitigating’ factors like provocation and increased by ‘aggravating’ factors, such as the macabre disposal of a body. Whole life orders are the starting point in any case where two or more murders are committed that involve a substantial degree of premeditation, or sexual or sadistic conduct. This also includes the killing of a child involving any of the above factors.

Schedule 21 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 operates as a guide to all sentencing judges in Britain. Section 4 (2) of Schedule 21 states that a whole life order applies in the cases of:

(a) the murder of two or more persons, where each murder involves any of the following –

(i) a substantial degree of premeditation or planning,

(ii) the abduction of the victim, or

(iii) sexual or sadistic conduct,

(b) the murder of a child if involving the abduction of the child or sexual or sadistic motivation,

(c) a murder done for the purpose of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause, or

(d) a murder by an offender previously convicted of murder.

Schedule 21 also states that to qualify for a whole life tariff the offender must have been aged 21 or over at the time of the offence.

Soham murderer Ian Huntley, who killed 10-year-olds Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman in his home in August 2002, did not have his minimum prison term set at his 2003 trial because the system on serving life sentences was being altered at the time. Instead sentencing was postponed until 29 September 2005 when the trial judge, Mr Justice Moses, had to consider the new principles set out under the Criminal Justice Act.

In deciding whether to issue Huntley with a whole life tariff, the judge had to consider the principles set out in Schedule 21. Explaining his decision not to issue such a sentence, Mr Justice Moses said the Huntley case lacked a proven element of abduction because the meeting between the girls and Huntley, while his then girlfriend Maxine Carr was away, had been by chance.

The judge explained: ‘It is likely that the defendant took advantage of the girls’ acquaintance with Carr to entice them into the house, but that could not be proved.’ He added: ‘Their presence in the house thus remains unexplained. There is a likelihood of sexual motivation, but there was no evidence of sexual activity, and it remains no more than a likelihood. In those circumstances, the starting point should not be a whole life order.’ Instead, the judge chose a starting point of 30 years and added an extra 10 years because the murders were ‘aggravated’ by Huntley’s abuse of the girls’ trust and his deceitfulness afterwards. He said: ‘The two children were vulnerable and obviously trusted the defendant because of his position in the school as caretaker and relationship with Carr.’

Sentencing Huntley, Mr Justice Moses emphasised: ‘I have not ordered that this defendant will not spend the rest of his life in prison. The order I make offers little or no hope of the defendant’s eventual release.’ Huntley will be eligible for release in 2042, by which time he will be 68 years old. Even then, he will have to convince the parole board that it is safe to release one of the most publicly despised killers in recent history.

The latest case to call into question the rules governing whole life tariffs came in August 2008, when cop killer David Bieber won an appeal against his sentence to die behind bars. Bieber, a former US marine, shot dead PC Ian Broadhurst during a routine check on a stolen vehicle he was driving in Leeds on Boxing Day, 2003. The gunman shot the policeman point-blank in the head as he lay injured on the ground pleading for his life. Bieber was also convicted of the attempted murder of two of Broadhurst’s colleagues as they attempted to flee the shooting. Three Court of Appeal judges held that the facts of the case,‘horrifying though they were’, did not justify a whole-life term because the ‘substantial degree of premeditation or planning’ detailed in Schedule 21 was not involved. Instead, Bieber was given a minimum term of 37 years.

Among the murderers featured in this book are a number of notable omissions, the most obvious being Britain’s most notorious serial killer, Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe, who was convicted in 1981 – before the inception of whole-life tariffs – of murdering 13 women. At his trial at the Old Bailey, Mr Justice Boreham ‘recommended’ Sutcliffe should serve at least 30 years before being considered for parole.

The Ministry of Justice says Sutcliffe is not on its official list of 36 whole-life sentence prisoners because his tariff has never been ‘formally’ set. As detailed earlier, from their inception in 1983 until November 2002, the tariffs for mandatory life sentence prisoners were set by Home Office ministers. As part of this process, prisoners were entitled to submit written representations to the Secretary of State before their recommended tariff was officially set. The representations gave the prisoner the opportunity to say what he or she thought the tariff should be and were typically prepared by a solicitor.

The Secretary of State would not set a prisoner’s tariff until the written representations had been made. Solicitors acting on Sutcliffe’s behalf did not submit these representations, presumably because they were well aware that his sentence would inevitably be increased from the judge’s recommended 30 years.

By virtue of Schedule 22 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003, the High Court is responsible for setting minimum terms for all those prisoners who, like Sutcliffe, were sentenced before the Act came into force but did not receive a tariff from the Secretary of State under the previous arrangements. There were almost 720 such prisoners when the Act came into force. The majority of these cases have now had a minimum term set by a High Court judge and several of them feature in later chapters of this book. Decisions on some cases have yet to be made. According to the Ministry of Justice, it is impossible to predict when individual tariffs on these prisoners are likely to be set.

Many of the killers on the official list of whole-life prisoners have appealed, without success, against their sentences. Others have accepted from day one that their crimes warrant the ultimate penalty available to British courts. Some are murderers who have killed again while out of prison on life licence, others are psychopathic serial killers who hunted strangers to satisfy an uncontrollable bloodlust. Several men featured within these pages are sexual perverts who killed to indulge their sick desires; other sexual killers snuffed out the lives of their victims simply to avoid identification. A few murdered purely out of greed.

Some of the killers you will have heard of, others you will not. What they all have in common is the fact that they will die behind bars.