Читать книгу Cautionary Pilgrim - Nick Flint - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMy father had ended his journey and mine was about to begin. This journey had been passed to me as a gift in the form of a much thumbed volume just as his own father some sixty years before had given the very same book to him.

Who can possibly say how many paths cross and how often, sometimes without obvious consequence, other times with significant effect at the time or interpreted as such much later on. Just a few days after the death of my great grandfather in a Sussex Workhouse, another man, twenty five miles away, was at the start of his own special pilgrimage. It was late October 1902, that man was Hilaire Belloc and the walk he was about to undertake is immortalized in the extraordinary book – an early edition of which I was now holding in my hand; my grandfather’s copy. I had long dreamed of making this journey and now the time had come.

I was standing, not as I’d once imagined I might be on the anniversary of the start of the actual walk, on the spot where it began, but instead where the book’s journey ended, where Belloc had bid his walking companions and the reader goodbye. My father had just died and as I read his inscription addressed to me inside the cover it was as if I heard his voice inside me and I knew that the journey had begun.

It was in that precise moment that I became self consciously aware that I was being observed. For how long this someone else had been there I don’t know, but as I met his eyes there was a smile and I immediately relaxed and hailed him as a fellow walker. ‘You are reading Belloc.’ He observed, and I nodded, thinking he must have good eyesight for a man of his age or perhaps some other gift? He looked to me to be approaching seventy years of age, upright and wiry and to be attired in some ecclesiastical garb modified for practical outdoor purposes. My inquisitiveness as to what this monastic looking figure might be up to was immediately wakened.

His rough blue grey habit owed, with its simple cut more to what might be seen around the fishermen’s huts of Hastings than in some grand monastic cloister. A dark heavy wooden cross hung high on his heart. His floppy hat had a seaside air about it too – and I immediately thought of it as his ‘Bless me Quick’ hat and wouldn’t have been altogether surprised to see that legend emblazoned on it.

Standing together on the Downs above Harting we were able to make out through the mists of autumn below, the distinctive copper green spire of Harting Church and clustered around it the few streets and dwellings that comprised the village that, depending on how you choose to look at it, is first or last in Sussex from the Hampshire border.

‘From today I am undertaking a walk of my own.’ confided the man. ‘A pilgrimage in fact’ he added. I nodded and smiled to which he asked ‘So, perhaps I may join you? After all, ‘a man is more himself when he is in the company of others’ he quoted, from the book which I had so recently been inwardly digesting, pressing his request with a knowing wiggle of the eyebrows, and that appeared somehow to seal some sort of pact between us. Nor was the company intrusive. His knowledge of Belloc or ‘Hilaire’ as he preferred to familiarly call him was to prove a bonus.

In repose his lined face bore a weary, even perhaps melancholy air. It was all the more remarkable that whenever he spoke or his eyes met another that his features, especially his eyes seemed animated by some quality that almost appeared to be an inner lustre. I was reminded the first time I noticed it of a flower responding to the sun and basking in the source of the light. His voice at first seemed high pitched in relation to his physique but it carried on the air with a note as clear as that of the oboe above the other instruments of the orchestra.

This may sound silly,’ he went on ‘but I am heading at least as much towards a time as to a place. In four days it will be the feast of All Saints. I pestered the brothers of my community to let me out for these few days on condition that I return with evidence of the holiness that so many seem sadly to have ceased to believe in. Like the countless forgotten saints it seems even the church may have lost hope in holiness and forgotten where it can be found. My destination is the festival of All Saints.’

‘From Sin City to Sanctity?’ I quipped, immediately regretting such a flippant, not to say dismissive sounding summary of such a sacred pledge, but ‘Pilgrim’, the name by which I now thought of him, to my surprise rather than assume any attitude of religious affront laughed heartily out loud. ‘Yes – laughter is often the first step, a healthy sense of the absurdity of things. I feel our friend was on that track, and the name his father gave him Hilaire – seems to have set him off and suited him perfectly in that respect.’

I reverently shut my copy of Belloc’s The Four Men, the inspiration for my walk and put it in my rucksack as we began walking together, to begin with at a slow pace. The first part of our walk with some steep climbing afforded opportunities to stop, appraise each challenging incline as one approached it and to stop again for breath when we had attained it. Otherwise we spent much time alone with our own thoughts only exchanging the occasional remark. I was out of practice as far as any serious walking went and was more than happy to adjust to the pace of an older man.

At the top of one of our climbs I shared my personal conundrum. ‘I suppose many have retraced Belloc’s journey across Sussex – I’m not sure why, but I decided to walk it backwards’. Laughing at the image that my words no doubt conjured up he immediately twirled round and began himself walking unsteadily backwards, feigning an expression of fear as he made his reply.

‘Perhaps you are more likely to bump into the elusive fellow than you would if you were pursuing after him down the years since he last walked this way. Maybe’ he added with mock excitement ‘There’s a chance we may catch him coming in the other direction?’ With the insertion of that one word ‘we’ it seemed as though I had suddenly acquired a companion not just for this stretch but for the county wide walk in its entirety. I began to think that rather than chasing a figure receding into history that Belloc might indeed be nearer than I had first realised. In fact as we talked it emerged we knew of only one other lover of Sussex and devotee of Belloc who had recreated the walk of The Four Men. Bob Copper, a Sussex folk singer of international repute had done it in 1950 and with a view to seeing how much the county and especially the roads had changed, repeated the exercise again in the early 1990s, of necessity devising an alternative route in places where the volume of road traffic had increased beyond the imagination of Belloc since 1950 to say nothing of the increase in the first half of the 20th century.

Bob had written an entertaining and informative account of his travels. He had walked predictably enough as Belloc had, from east to west, whereas by doing it ‘backwards’ I was starting at Harting, almost in Hampshire with Robertsbridge on the border with Kent my destination. The singer had probably been of a similar age to Pilgrim when he last completed it.

We had stopped once more to look down on the peaceful morning scene below. Through a break in the trees we saw framed a perfectly square field below on which sheep appeared to have been placed like pieces in order ready for the start of some Downland giant’s board game. From somewhere much nearer however the plaintive bleat of a sheep piercingly if weakly and intermittently, carried on the breeze. Instinctively we looked for the source of the cry and then I saw clearly a sheep that had rolled onto its back and was struggling to get right way up. Immediately I came to the rescue and it was in that moment as I picked the poor animal up that I felt I had grasped the real fabric of the Downs themselves, of which for generations these flocks and their faithful shepherds were surely the rightful inhabitants.

Seeing the tuft of wool left in my hand Pilgrim said ‘Put that in your boots. There’s nothing like sheep’s wool to cushion your feet against blisters, and it’s better than holding it in your hand as the shepherds liked to be buried. For them it was a passport to show Saint Peter they had a reason for irregular church attendance.’ He had resumed his backward walk as he dispensed this wisdom, but just as he said this, a few yards ahead of us off the path a movement and splash of colour alerted me to the presence of someone sitting in the grass, unseen of course by my apparently careless companion who suddenly seemed in danger of tripping himself or trampling the figure behind him. I gave a cry to look behind him and as I caught up the man got to his feet thinking he would have to allow the backwards walker past. The man we had disturbed was holding a small sketch pad on which a pencil drawing could be seen.

‘I’m sorry’ my new friend said to the stranger although I have to admit that he didn’t look excessively contrite. ‘We were experimenting as regards the virtue of walking backwards.‘ There was a pause as the man seemed to be taking this information in.

‘A good way of not getting lost’ replied the other ignoring the narrowly averted injury to himself. ‘Every once in a while it is good to look back and memorise the scene behind you. If you take a wrong turn and have to retrace your steps you should be able to almost instantly recognise the way you’ve been.’

‘Very practical’ I replied, the novice walker that I was, suitably impressed. I noticed that when he spoke there was the slightest trace of some accent I couldn’t quite identify. It suggested to me that he might have travelled a long way with his pad and pencil to make this appointment with us. He was what in times past the Sussex native would have called, without any trace of unfriendliness a ‘furriner’. His complexion was dark and his tight curly hair completely white, but whether this foreigner was from Russia, Germany, perhaps the Middle East or even Kent, my ear could not detect with certainty.

‘Well I have a visual approach to life’ he replied, interrupting my thoughts, brushing himself down and holding up his drawing pad ostentatiously before replacing it in some pocket about his person.

‘We are on a pilgrimage’ my companion offered by way of explanation. ‘My friend is looking for a certain Hilaire Belloc. I am looking for saints. I fear that my church has stopped believing in holiness so my community let me out on a field trip to see if I could find any.’ He made them sound like some rare kind of butterfly.

‘And walking backwards helps you spot them?’ asked the newcomer, with apparent seriousness.

‘Er, could be… perhaps we recognise as saints those who have tended to go against the grain, choose a different direction, swim against the tide.’ As Pilgrim said this he peered around as though some might be nearby in the long grass or caught in the gorse bushes.

In the presence of this third party I became embarrassingly aware that the moment for introductions had come, but I did not know the name of my fellow walker. I was about to come clean when Pilgrim asked him ‘you’re an artist?’

You could call me a sort of scribbler I suppose and you?’

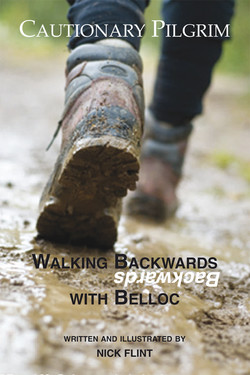

‘I am only a pilgrim, Scribbler and happy to be known simply as that. It is good to be joined by a scribe of the kingdom of Heaven who out of his treasure can bring forth things both old and new.’ I congratulated myself that the name I had chosen for Pilgrim was one he felt himself so perfectly close to the mark. There was a pause as they both looked at me. Who was I? I wondered if that was for me to discover; the unspoken question on this journey. Both sensed my hesitation. ‘Your journey is a pilgrimage too.’ said Pilgrim but the purpose is perhaps not as clear to you yet as mine might seem to be. I think Hilaire would respect your reticence; he would perhaps call you a ‘cautionary pilgrim.’ I smiled at the reference to the poet’s perhaps best known and most enduring if not most profound verses and thanked Pilgrim and Scribbler, but at the same time I knew I was searching for a greater confidence in myself.

As if reading my thoughts Pilgrim said ‘Caution is no bad thing in itself of course, and yet taking risks is liberating. The saints I’m looking for have often been judged foolish or silly, but in this part of the country we know ‘silly’ comes from the old word selig meaning blessed or happy. Silly Sussex has more saints per square mile than any other English county.’ I was not in a position to contradict the assertion, but my respectful silence was immediately broken in an agnostic tone.

‘Why should that be?’ asked an astonished Scribbler ‘What does Sussex have that no other county can boast?’ in reply Pilgrim calmly pointed to the ground on which we are walking and gestured towards the soft contours of the Downland landscape spread out green ahead of us and on either side. ‘Have either of you been to the Holy Land of Our Lord’s birth and ministry?’ We shook our heads, almost apologetically, certainly in deference as we sensed we were to be made privy to a matter of deep wisdom and insight.

‘The chalk Downs are nothing less than the landscape of the Bible’ Pilgrim declared. Long ago Palestine lost, through a changing climate the lush green that clothed its hills. If you took away the grass you would see the line of these gentle hills to be just the same as the Judean desert. When you traverse the chalk desert between Jerusalem and Jericho just as the Good Samaritan did, you are treading the same kind of terrain that forms our weald or and their wilderness – the words even mean the same; the weald means the wild. This land too is holy to God. We are also walking with our Lord on the sea.’

This last comment drew surprised looks from us both. Having our full attention, Pilgrim elucidated.

’Chalk is made of the remains of marine creatures which once formed the inhabitants of a vast sea, although that sea parted centuries before humankind ever arrived to walk over on dry ground there.’ I looked in wonder at Scribbler who I saw blowing out his cheeks and miming an underwater swimming action in slow motion. Sheepishly he stopped doing this as he saw us both look at his performance with amazement and recovering himself said, adopting a serious even scholarly tone.

‘Is there perhaps a memory of this in the Sussex churches that put fish emblems atop their spires? ’ I chuckled at the thought as did Pilgrim but…

‘Yes, possibly, and those same churches recall the saints who swam as it were against the current and prevailed in the strength of God if to the confusion of many’ added Pilgrim. ‘Consider James Hannington who on 29th October this very day as it should happen some one hundred and thirty years ago met his end violently at the orders of a ruthless tyrannical King of Uganda, simply because he brought the message of Jesus to that part of Africa and challenged the authority of such a despot. Hannington, a Sussex lad grew up in privileged circumstances north of Brighton. It is said his last words before being speared to death were ‘ I have purchased the road to Uganda with my blood ’ and it is true that the church has flourished in that part of Africa ever since.’

‘Our road by comparison seems a most welcoming and friendly one.’ murmured Scribbler thoughtfully. ‘HB picked up the skills of a draughtsman in early life.’ he went on. ‘It stood him in good stead when once with typical romance he tramped, almost penniless, across vast regions of America. He would pay his way by sketching local scenes in exchange for bed and board.’ During this speech, he had taken out his own pad and pencil and been intent on producing a drawing which he now showed us. At first glance it looked like one of the sturdy trees that steadfastly guarded the path but as we looked more carefully we detected a human figure seated on an old tree stump.

Not long afterwards we entered the shelter of some trees. Following recent high winds the ground was thickly carpeted with leaves and several large branches lay blown down around us. As our eyes grew accustomed to the dark we perceived a waiting figure sat precisely in the pose Scribbler appeared to have foreseen. She was a slight figure, not young. Her demeanour suggested the essence of purposeful waiting. Sitting very still, her steady gaze put me in mind of an owl and I don’t think I would have been perturbed in the least to have seen her flutter up into the branches of the imposing ash tree under which she sat, and resume her gaze from there. Instead she rose to her feet and with a smile walked towards us. No words were spoken immediately. It was if we had come together by appointment. She looked at me enigmatically ‘That wool in your boots,’ she said ‘may prove useful to weave into a tale or two.’

She spoke in an accent that left me with an impression of how I imagine my own Sussex ancestors might have spoken. They say the Sussex accent is long gone and I remember my father telling me that as a young man in the army he had been specifically trained to lose his distinctive rustic drawl, but I sensed there was a time when her accent might have marked her out not just as Sussex, but to the ears of true Sussex folk as from some precise hidden hamlet or village where her family might have lived for generations.

Pilgrim looked at me. ‘Is it enough that we are now four?’ he said, raising his eyebrows, ‘Does it matter that one of the little flock is not a man?’ Sometimes one hears a word which must be seized on to and hidden in the heart. I thought this as Pilgrim added mysteriously ‘we are all knit together in one communion and fellowship with all the saints in heaven and on earth.’

The three of us gave this lady of the woods an appraising but not unfriendly look which she returned in equal measure ‘She looks like someone who knows.’ commented Scribbler comparing his sketch with the figure seated in front of him.

‘Who knows’ she echoed mysteriously and again making me think of an owl. At this Pilgrim announced ‘We will christen you ‘Who Knows’. For a moment I feared he might literally dampen this new friendship by actually splashing her with some of the water from the drinking bottle he produced from the kangaroo pocket in his monastic smock, but he was merely brandishing it before taking a swig. ‘I am Pilgrim, this is Scribbler.’ I felt in awe of this living embodiment of the spirit of the woods, but found the courage to ask ‘Do you know whether you would like to join us on a walk through Sussex?’

‘Certainly,’ she responded, and immediately divining that perhaps the three of us were not best organised asked ‘Now we won’t make many miles before dark – have you given thought to where we might lodge tonight? It was true we were weary and the light of day was fading. In answer to our blank looks and mumbles she gave a reassuring smile. We were led downhill by her to where signs of human habitation showed us to have arrived at the outskirts of the village of Duncton. Walking single file along a footpath we emerged onto the main road opposite the church near where we waited. Before we knew it, a large shining vehicle like Elijah’s fiery chariot had stopped, doors were flung open and we were on our way to a nearby cottage. This turn of events came about through the network of church and community in a small village where trusting folk still welcome the stranger and revive them with good food and wine.

Much of the evening was spent planning the next stage of the walk in which we had found ourselves thrown together. We passed the book round, read extracts aloud to one another and pondered many aspects of the tale, each of us identifying with one or another of the companions.

But were there actually four of them?’ Who Knows suddenly asked. She appeared to know enough of the subject to see how certainly each of the characters was in all probability a facet of the author’s personality, interests and temperament.

Belloc took the name ‘Myself, Grizzlebeard was a philosophical man of the world, Sailor and Poet simply described two of Belloc’s favourite occupations. ‘Perhaps the other three are nothing more than a literary device; mix them together and out could come Grizzlepoet, Mybeardself or Sailbeard!’

‘You might as well ask whether the church’s doctrine of the Holy Trinity is a mere device.’ Pronounced Pilgrim thoughtfully ‘I say it is how the story of God is experienced. It may not be coincidence either that the Gospels give us four familiar but distinct faces of holiness to ponder.’

‘When HB and G K Chesterton first became friends they were described by George Bernard Shaw as ‘the quadruped Chesterbelloc’ said Scribbler.

‘Belloc was a Christian thinker of course.’ I said leaning forward to venture an opinion. ‘Maybe his book was subconsciously about his relationship to God in three persons, or perhaps the four men are the four evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke and John?’

‘Belloc and his companions consumed copious amounts of ale on their trek’ I observed. ‘D’you think if the other three were imaginary, that he drank for them as well?’

‘That’s certainly as may be.’ nodded Pilgrim, ambiguous as to which of our questions he was answering. Then slowly and deliberately stretching his tired neck and arms ‘Now a challenging walk lies ahead of us in the coming days and I suggest we retire early to prepare ourselves with as much rest as I am confident we will need. I feel sure that our own walk will reveal its own surprises and mysteries.’