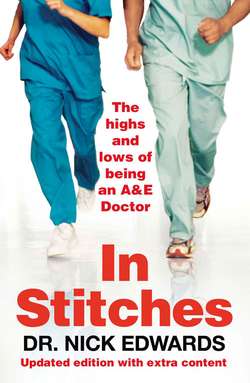

Читать книгу In Stitches - Nick Edwards, Dr. Nick Edwards - Страница 5

Introduction

ОглавлениеIt was a fairly standard Saturday at work; generally busy and stressful but interrupted by episodes of upset, excitement and amusement. However, being honest, I quite enjoyed myself. I found pleasure in successfully treating someone’s heart failure and liked being able to mend a patient’s dislocated shoulder. I was amused by a drunk and injured tough-looking biker-type who had got into a fight over a game of chess. And I had a quite fascinating conversation with a man in his late 80s (who came in after a car accident), who insisted on telling me about his current sex life difficulties. Overall, if you have got to work, then working in A&E (Accident and Emergency) is one of the most interesting jobs I could think of and I am glad that it is the job I do.

Admittedly, I got mildly frustrated by the sheer number of patients who were revelling in the British culture of getting as pissed as possible, starting a fight and then coming in to A&E. And yes, I got a little weary of seeing a number of patients who had not read the big red (and quite explicit) sign as they walked in, and who had neither an accident nor an emergency and should have seen an out-of-hours GP (if one had been more readily available). However, overall, I saw a lot of patients who genuinely needed our services and whom we could help, which is the bit of my job that I love.

There was one patient that I took an instant liking to. She was in her mid-80s and had such a fast wit and spark to her personality that she felt like a breath of fresh air as I was treating her. She touched my emotional heartstrings because she reminded me of my Great Aunt.

She came in after having collapsed at home with abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhoea. We were busy and she had had to wait 2 hours to see me. I quickly made the diagnosis of a possible gastro-enteritis (stomach bug), gave her some fluids, took some blood, organised an X-ray and arranged for admission. I wanted to wait for the results, spend more time with her and manage her care accordingly, but in a flash she was whisked away to a care of the elderly ward for me never to see her again. An hour after she arrived on the ward (and before she was seen by the ward doctors), she suddenly deteriorated and her blood pressure fell. This wasn’t noticed as quickly as it might have been had she stayed in A&E as the ward nurses were so rushed off their feet (two trained nurses having to look after 24 demanding patients).

She had been rushed out of A&E to get her to a ward so that she wouldn’t break the government’s 4-hour target (and because the A&E department has not got the resources to continue safely caring for patients for longer than a few hours in addition to seeing all the new ones constantly coming through the doors). I also had to pass responsibility over to the other doctors before her blood tests were back and before a definitive diagnosis was made. I later learned that she had been anaemic, which had put stress on her heart, and that she then ended up on the high-dependency ward, needing a blood transfusion.

For a while it was touch and go as to whether she could be stabilised. I couldn’t help wondering whether, if she had remained in A&E, under our care, all these problems could have been treated sooner and the complications avoided. However, this was not possible as, apparently, I had more pressing priorities. My next job was to go and see a bloke who had called an ambulance to get his ingrown toenail looked at and who had been waiting for 3 hours. He had, incidentally, had this problem for five weeks and wanted it (in his words) ‘sorted out now, as I’m off to Ibiza tomorrow, mate’.

I felt really frustrated. It didn’t need to be like this. Why does the ‘system’ have to impede me from caring for my sick patients and make me worry about figures and targets instead?

When you are surrounded by death and disease, aggressive and drunk patients, and nurses (male and female) trying constantly to flirt with you, it can make working in A&E an interesting and often stressful environment. However, it is the management problems and the effects of the NHS reforms, implemented without thinking about the possibilities of unintended consequences that really drive doctors and nurses mad. More importantly, they distort clinical priorities and can damage patient care. Surely this is not what the government intended? How have we drifted away from the original ideals of the NHS?

In July 1948, Nye Bevan presided over the creation of the NHS. It is a service that provides free care based on need and not ability to pay; to care for us from the cradle to the grave. It was the envy of the world and the greatest example of social policy this country has ever implemented. It is a wonderful institution that needs protecting and nurturing. Its desire to protect health and not profits means that its efficiency could outstrip that of any other health system in the world. The very thought of working for it filled me with pride.

By 1997, years of underfunding had left the NHS in a perilous state. Massive influxes of money from Blair and Brown poured in, which helped bring in some great improvements in service and much-needed reforms. This is especially true in A&E, where things have improved greatly from the days of patients spending days in corridors on trolleys waiting for a bed. The target brought in was a 4-hour rule stating that 98 percent of people have to be seen and admitted or discharged within 4 hours. Initially, it was a necessary but blunt tool, which effectively brought about urgently needed change. However, its lack of subtlety and implementation without resort to common sense is now impeding care and distorting priorities.

Despite the enormous sums of money that have been spent, for the NHS as a whole the overall benefits have been underwhelming. In the last few years, the government has managed to demoralise a significant number of hospital workers despite these huge increases in resources. To try and get ‘better value for money’ targets have been implemented and reforms made that threaten the structure, efficiency and ethos of the NHS, driving it away from cooperation and caring towards incoherence and profit making. For those of us who believe in the idea of collectivism enshrined in the NHS, it is a worrying time. It is an especially worrying time if you live near a hospital that is under threat of closure or losing its A&E in the name of ‘reforms’.

These worries about what is happening to the NHS (and in particular A&E) combined with the general demands of the job, can sometimes make me feel a bit stressed. Many people cope with this by drinking; however, I usually have to stop after a pint, as I start to feel sick and get a rash. Instead I started ranting to my friends and moaning to my wife: she started to threaten divorce and my friends seemed to invite me out less and less. So, in an attempt to save my sanity and marriage, I turned to writing down my frustrations with the job. A cathartic form of literary therapy.

That is, in part, what this book is about. It is a collection of stories written to try and explain what working in A&E is really like. It is not just about the frustrations – far from it. I have also tried to provide a small indication of the buzz I get from work and the amusement and banter that can be found there, including the dark humour that is used to cope with the stress of the job. I have tried to describe the joy I get from observing the eccentricities of the human condition and the fascinating little ironies life throws upon us. I have, in addition, tried to cover more serious aspects of the problems facing today’s NHS and A&E departments in particular. All the stories are typical of ones retold in staff coffee-rooms up and down the country. They are based on events that have happened to me, or colleagues, working in various hospitals throughout the last six years. However, details have been changed and the stories described are often an amalgam of many similar incidents rather than one specific case. If you think you recognise a clinical situation or problem, it is probably because it is repeated daily in all A&E departments.

This book is certainly not a whistle-blowing exercise, as the situations described are universal problems and not specific to one hospital. I certainly feel that the departments I have worked in are good and the consultants have been supportive. The way they manage to provide top-quality clinical care despite the management concerns occurring in the background, provide me with appropriate role models. Neither is this book a blog as such (although the idea started out as a blog) – there is no real-time order to the various passages. There is no underlying story and neither are the stories arranged into any theme. It is just a random selection of events and experiences as an A&E doctor.

I hope you enjoy reading it – both the amusing and sarcastic bits and the ones where I am being serious. I hope to inform you what really goes on in your local A&E and what the people working there are going through, so that if you happen to need our services, you will understand when things don’t work as smoothly as perhaps they should. The views and ideas in the book are my own and are not endorsed by any political organisation or pressure group. I am not a politician or a manager, but I do work on the ‘coal face’ of the NHS and can see its problems.

I don’t think the NHS is having its best year ever. I think all the recent reforms and targets and private sector involvement are really making things go a bit ‘tits up’. I want to share with you some of my concerns and how they affect my working life, as well as showing you the real highs and lows of life as an A&E doctor. Thank you for reading.

Dr Nick Edwards, July 2007

P.S. For those of you who want a quick summary of what life is like working in A&E, without having to read the book, then here goes. It is a bit like what you see on TV programmes such as ER, but with less sex and more paper work. I, unfortunately, do not look like George Clooney either – more like Charlie out of Casualty. I have also never asked for a ‘chem 20 stat’ and the medical students are not usually as beautiful or as helpful as the ones depicted in ER.