Читать книгу Move Under Ground - Nick Mamatas - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

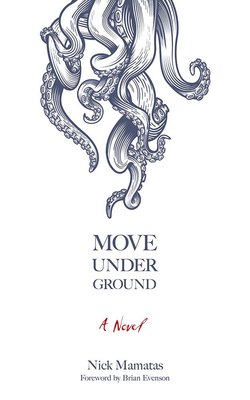

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

AT FIRST glance, the concept of Nick Mamatas’s first novel, Move Under Ground, sounds like the kind of thing you’d think up when very, very stoned. You and your buddy are sitting on either end of the couch, your best bong between you, multiplayering Doom 3 (Move Under Ground was originally published in 2004, after all). You start talking about how awesome Lovecraft and his contingent of Elder Gods are, and he responds, “No, man, Kerouac’s On the Road is where it’s at.” You argue, but after a few more flicks of the lighter you simultaneously come up with the brilliant idea (dude!) of writing a book that combines both Kerouac and Lovecraft. A book both of you can love.

Usually such ideas don’t survive in the cold, sober light of day. They’ve lost their sparkle, maybe, and no longer appeal. Maybe they weren’t as good of an idea as they seemed when your state was altered. Maybe you simply slept the idea off and forgot you ever had it. Or maybe you realized that actually writing the book would be a lot of work.

But Mamatas didn’t forget, and he isn’t afraid of work: he actually wrote the book. The amazing thing about Move Under Ground is that it approaches what could be an absurd premise in a way that actually works. Not only works: it’s stunningly good.

Move Under Ground is a strange little telepod experiment that brings together styles and concepts from two different writers and two different genres to create something altogether different from either one. One reason the novel is good (besides the strength of the writing itself) is that Mamatas is not an acolyte. He views both Lovecraft and Kerouac with a critical eye, clearly aware of their strengths and flaws both as writers and as human beings. So much writing that follows in the furrow Kerouac drunkenly plowed is slavishly imitative, replicative, and ends up reproducing some of the clumsiness of Kerouac’s writing without capturing his verve and velocity. Similarly, many 21st century stories written in a Lovecraftian vein are little more than pastiche: they just make you wish you were reading Lovecraft instead (though admittedly many of Lovecraft’s own stories make you wish you were reading another, better Lovecraft story instead). But Mamatas begins in an altogether different place. He is not a joiner or a follower; he is the kind of writer who is deeply engaged but skeptical, not willing to accept anything on faith. He is less interested in imitating either Lovecraft or Kerouac than in seeing how the sparks fly when he makes the Lovecraft and Kerouac vehicles have a head-on collision.

There’s something exhilarating about the specificity of the genre combination here. Often when writers combine or straddle genres they do so in a way that’s fairly loose, but here it’s quite precise. In that specificity, Move Under Ground was ahead of its time: it reminds me more of the sophisticated genre hybrids people started publishing about ten years after the book was first published. Move Under Ground is also the opening salvo in a larger critique and questioning of genre as a mechanism of control that Mamatas has engaged in across all of his books. You should be determining and directing the genre, rather than giving in to its clichés and allowing the genre to determine you.

Mamatas takes from Kerouac his fluidity, his sense of tumbling progression, but after a chapter or so he torques this, shows how such a voice has to be transformed once shambling shoggoths stand in the place of squares in this void-cursed version of America. And yes, Lovecraft’s beings are here, but they’re torqued as well, integrated into the social structure of America but only visible to those who know how to perceive them, those whose perceptual doors have been blown wide open—kind of like John Carpenter’s They Live but with Beat enlightenment in the place of special sunglasses. Neal Cassady, the individual who seems most aware of the Elder Gods and the most interested in trying to manipulate them for his own purposes (when he can stay focused, that is), is very different from the tortured occult-obsessed seekers found in Lovecraft’s stories. He’s also a seeming expert in self-deception, in convincing himself to do what he obviously shouldn’t: “I think I should give myself over to the Dark Dreamer, and then, bound to that power, I can use it to protect reality from the on-rushing chaos overhead.” In other words, give yourself to chaos to protect yourself from chaos—what could possibly go wrong? Or as he says a page later, “Maybe it’s not so bad. Is it really any worse than what happened before? People killed themselves for reasons just as foolish. People go to work, stuff themselves full of meat, get down on their knees and wail before something or other, crap out babies from bloody crotches, then feed the worms. . . Is it even any different?” I think the argument of the book is that it most definitely is, and that self-deception seems to be as rampant in the turn on/tune in/drop out generation as it is in the squares. Even if you thwart Cthulu, if you’re not vigilant you might still end up becoming the very thing you’ve been fighting against. After all, writing On the Road wasn’t enough to save Kerouac from becoming the kind of person who ineffectually yelled at the hippies on TV as he drank himself to death in his mother’s house.

The writing in Move Under Ground is a little like Kerouac, enough to give the feel of him. It owes a great deal less to Lovecraft’s often purple prose, but there’s a thickness to the patterning, an imagistic density, that strikes me as the kind of thing I wish Lovecraft had done more often. Mamatas manages a retooling and re-engineering of both Lovecraft’s style and Kerouac’s style into a new seamless and rollicking whole. China Miéville says it as well as anyone when he calls the book “An intense, inspired crossbred bastard homage-cum-critique-cum-vision.” That, for me, is one of the great things about Mamatas’s work, and what separates him from lesser writers: he knows he doesn’t have to choose. He understands you can have an homage that is also a critique and that also, ultimately, opens up an entirely new horizon—that all these things can work with and against one another in a complex way.

Kerouac may be the central character, but, as I’ve said, Cassady is there as well, often as a focal point, as he is in On the Road—though for good stretches of the novel he is absent, with Kerouac trying to find him. Even when he is there, it’s not altogether clear that it’s really him who’s there. Just as important is William S. Burroughs, who only shows up about halfway through, and who strikes me as the book’s defining spirit. Indeed, Move Under Ground implies that if you combine Kerouac and Lovecraft you might end up with something that reads a lot like Burroughs, at least in terms of content (no cut-ups here): the shoggoths are bugs of a sort, which seems decidedly Burroughsian, and they are called mugwumps as well, like the creatures found in Naked Lunch. As Mamatas’s Kerouac says of Burroughs, “Of course he didn’t care about the beetlemen, they may as well have run off the pages of his own damn book.” There’s something deeply weird about Burroughs in general, and tonally Move Under Ground recalls Naked Lunch and The Nova Trilogy. Burroughs’s sensibility, more than Kerouac’s, seems naturally receptive to the vibrational frequency of weird horror.

Ultimately Kerouac finds himself somewhere in the middle ground between Cassady, who wants to embrace the darkness, and Burroughs, who is out to kill all these goddamn bugs. He has to figure out how to properly thread the needle between these two to prevent the world from ending. Where that, ultimately, leaves Kerouac is the subject of the Epilogue. By keeping the world from going to hell, as it turns out, he may have simply chosen a different, more personal form of hell.

Move Under Ground is, in addition, a scalpel-sharp demythologizing of On the Road and of Kerouac in general. It has a similar maddened carnivalesque feel to it as Robert Coover’s The Public Burning, in which Richard Nixon is buggered by Uncle Sam, or A Political Fable, in which the Cat in the Hat runs for president, to be eventually skinned alive and eaten. But Move Under Ground is a darker carnival, its ribald touches rarer. That’s not to say that if you’re a fan of Lovecraft or Kerouac you won’t find a lot to enjoy here: you will. One of the joys of the book is that bi-focused reading, the remembering and reconsideration of the stories and authors behind this book as you see how Mamatas is playing with them. The thrust of that is essentially metafictional: as well as having an engaging and crazed plot, this is a book about how Lovecraft and Kerouac’s writing works, about how they both succeed and fail, about how to both acknowledge them and move beyond them.

All in all, Move Under Ground is a smart critique of two writers who are too often not subject to real, informed critique. It ends up ricocheting off both of them to get somewhere entirely different than either of them manages to get on their own. It’s a radical book very much ahead of its time, strange and highly original, and well worth the read. Enjoy.

Brian Evenson