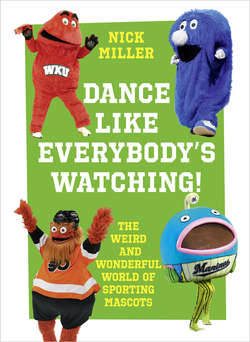

Читать книгу Dance Like Everybody’s Watching!: The Weird and Wonderful World of Sporting Mascots - Nick Miller - Страница 7

ОглавлениеAdam Glanzman/Getty Images

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MASCOTS

As ever with these things, nobody is sure who or what the first mascot was, the facts lost in the mists of time.

The word ‘mascot’ itself can be traced back to medieval Latin, in which masca meant ‘mask’ or ‘nightmare’. From there it made its way into 18th-century France, where mascoto loosely translated to ‘witch’ or ‘sorcerer’. This became a slang word, mascotte, essentially referring to a lucky charm or talisman, usually associated with gambling, but the first time it was really applied to sports teams was in the 1880s in the United States.

At that stage these ‘mascots’ were usually small boys adopted by clubs, which isn’t quite as sinister as it sounds. There was a kid named Chic who is mentioned in some books; he was not connected to a specific team, but was regarded as a good-luck charm by some baseball players; the Chicago White Stockings were led in parades by a boy named Willie Hahn, who would hold their flag high; and the St. Louis Brown Stockings were associated with ‘Little Nick’, whom the Sporting Life magazine described as ‘the luckiest man in the country’, and who supposedly passed on this luck to the team. Sportspeople being inherently superstitious, the idea of anything that could bring a little extra fortune was heartily embraced.

As sports became more organised around the turn of the 20th century, mascots generally became live animals. The oldest mascot is probably Handsome Dan, a bulldog that belonged to a student at Yale in the 1890s, and stuck around: there have been 17 subsequent Dans, the name passed on down the generations of Yale bulldogs, and No. 18 is going strong at the time of writing.

Inevitably, being connected to a university, Handsome Dan has been the subject of various kidnap-related japes, the first coming in 1934 when the editors of The Harvard Lampoon abducted him ahead of a big game between the rival institutions. You had to make your own fun back then.

Over the years countless real animals have been used as mascots – horses, pigs, goats, birds, huskies, rams, bears, lions, tigers – some connected to team nicknames, some seemingly entirely random. Plenty have been paraded at games, but some – most notably the tiger and the lion – would probably be regarded as something of a health and safety concern, and are kept to the realms of the conceptual.

All of these examples are from American sports, and it would be easy to assume that the mascot was a concept born and developed in that country, something rather too gaudy for the much more prim and proper English. But it’s simply not true. Zampa the Lion, for example, Millwall’s mascot named after the road that their stadium is on, has been around for nearly a century, and not just on the club’s badge. Zampa has existed in corporeal, furry form for most of that time, at various points looking like a slightly deformed cousin of the lion from The Wizard of Oz.

England is also where we find the first mascot for a World Cup. World Cup Willie – a lion dressed in a Union Flag shirt and shorts – was designed in five minutes by an illustrator called Reg Hoye, and also came with a song by skiffle singer Lonnie Donegan. He inspired other tournaments to try their own mascots, but perhaps unsurprisingly ‘League Cup Les’, attempted a year later, didn’t quite capture the country’s imagination.

By the 1950s ‘character’ mascots started to emerge, the first probably being Mr. Oriole, mascot of the Baltimore Orioles, who emerged in around 1954 but soon faded. Not long after came one of the most famous and best loved: Mr. Met, initially just a cartoon character on scorecards for New York Mets games, was fully realised in 1964 when a full-sized, costumed version began making appearances at Shea Stadium. When you explain Mr. Met in mere words – he’s a man with a giant baseball for a head – he sounds deeply weird, to say the least, but somehow still works. Although ‘retired’ for the better part of two decades, he was eventually revived after a campaign by fans in the early 1990s.

A big reason why he was quietly ushered away from the spotlight was the emergence in the 1970s of what we know today as mascots, the larger-than-life, Muppet-like creatures that you’ll see throughout this book.

The San Diego Chicken was the first, initially a promotional character for a radio station called KGB-FM (meaning he was somewhat menacingly known as the ‘KGB Chicken’ for a spell), but who became adopted by the San Diego Padres when the man who played him decided he wanted to get into games for free. The Chicken, zany antics and all, proved wildly popular, and copycats followed, the most notable being the Phillie Phanatic, broadly regarded as the model for the modern-day mascot.

These days you’ll struggle to find a major sports team, tournament or organisation that doesn’t have – or hasn’t had – a mascot, for better or worse. It’s almost a separate industry in itself; with every mascot comes merchandise, personal appearances, commercial endorsements and myriad other money-making schemes. They’ve come a long way from a dog that some students stole in the name of banter.