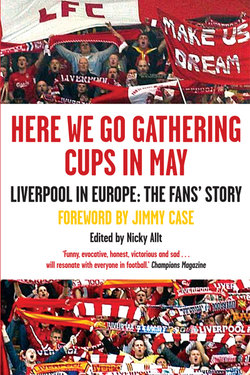

Читать книгу Here We Go Gathering Cups In May - Nicky Allt - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Leaving of Liverpool

ОглавлениеIf I was going on a five-day trip abroad next week, I’d pack a small case or a hefty sports bag with five pairs of undies and socks, a few changes of clobber, toothbrush, paste, shampoo, razor, foam, a bit of aftershave and some books to read … you know the score. At around half three on Monday 23rd May, me and our kid left me ma’s carrying two little plastic Co-Op bags with six sarnies and an apple each … and that was it. Honest to fuck, not even a comb. And the only reason we took apples is because our kid said, ‘They’ll clean our teeth.’

When we met the others, they had similar bags. Peter, the lad on the dole, only had crisps and Coke. It was a mixture of foreign-trip inexperience and couldn’t-give-a-shit attitude. Our kid summed it up: ‘It’ll do till we get to the boat.’

Standing at the bus stop outside the Park Brow pub in Kirkby was special. I really felt like somebody. We were all decked out in scarves and hats, and our kid and Peter had flags draped around them. Every car that passed blew their horn. On the bus we were treated like royalty. The driver didn’t charge us, and people on the top deck offered us ciggies and talked about the mass exodus. One fella said that his brother-in-law raised his trip money by selling his Ford Capri then telling his bird that the car had been robbed. There were all sorts of stories like that. Peter sold his entire record collection – about forty LPs and sixty singles. Our kid’s mate funded his trip by packing in his job as a sheet-metal worker so he could get his hands on the severance pay. The pawn shops got absolutely battered with hocked jewellery … in many cases unbeknown to the wives or girlfriends. Odd-job men were at an all-time high. Everywhere you looked, there were houses getting painted and gardens being mown.

I remember a Kopite who was always in Church Street playing a classical acoustic version of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, with a bucket that said ‘Busking for Rome’. The Echo ran a story about a lad from Speke who did a sponsored run dressed as a Roman gladiator, with all monies (after his fare) going to charity.

There were also more dodgy ways. Scrapyards put the price of copper down after hundreds of empty houses and flats around the city were stripped clean. A few Reds I knew from Huyton financed their trip by travelling round the north-west blowing water into fruit machines with a straw till the machines went haywire and paid out for any sequence. They also mastered the art of taping up ten-pence pieces with electricians’ tape then using them as fifty-pence pieces in ciggy machines.

Two brothers who drank in the Kingfisher in Kirkby got their trip sorted in one weekend after going to Blackpool and snaffling sets of chrome wheel trims from parked coaches (sixty quid per set). They’d never stolen a thing before that and have never done since. A well-known Kopite from Netherley got his fare together by going round putting people’s electricity metres on the fiddle for a pound a time. Then there were the famous Scottie Road shop hoisters who, in the spring of ’77, were lifting more shirts than Freddie Mercury and Elton John put together. It was a case of getting to Rome by any means without harming anyone. Everyone seemed to rally round and help each other out. I gave a lot of my diesel money away. I didn’t want it back; that’s just the way it was. Don’t get me wrong, there were a few no-marks and arseholes in the city, like everywhere else. But they were few and far between. There weren’t so many people with ‘I’m all right, Jack’ or ‘fuck-thy-neighbour’-type attitudes. These were the days before rag-heads, bag-heads, scag-heads and fuckin’ Thatcher. Harmless scallywags, yeah; scumbags, no … you know the score.

When we got to town, it was bouncing. The streets and bars around the station were wall to wall. Some of the costumes were fantastic: ten-gallon hats, top hats, bowler hats, red jumpsuits, white boiler suits, rosettes as big as sunflowers. The excitement and buzz was like nothing I’d ever experienced. Fellas were getting off buses and out of taxis then punching the air through gritted teeth before shaking hands with anybody. Some even hugged like the Reds had just scored a goal. It was obvious that this was something special. All together, 5000 of us were making the journey on twelve specials. One left early afternoon; the rest of us were due out in the evening.

Flags were draped inside pub windows – mostly home-made. There wasn’t enough room to roll a ciggy in the Crown, the Yankee bar and the Big House. Round in Casey Street a giant conga was snaking up and down singing ‘Let’s all go to Roma, let’s all go to Roma, na na na na’.

The ‘Arrivederci, Roma’ song had lads stopping women in the street and dancing slowies with them – all the birds happily obliged. A bearded tramp wearing a red and white plastic bowler hat was dancing around singing ‘Ee ay addio, we won the Cup’. I don’t know if he’d had a premonition or if he was just blagging it, but it did the trick – loads poured ale in his glass and filled his hat with loose change.

One of me mates, Vinnie, was gonna try and bunk the train. He was meeting us in the Star and Garter boozer at the front of St John’s precinct. The singing in there was deafening: ‘Liverpool are magic, Liverpool are magic, na na na na’. It took us about fifteen minutes to get from the entrance stairs to the bar. Our plastic carrier bags were a nuisance. It was all ‘Hold that while I go the bar’, or ‘Mind that for us while I go for a piss’. Ninety per cent of Reds had one.

Some lad had it sussed. He’d threaded and tied his carrier-bag handles through a belt-loop on the front of his jeans while he pretended to play the guitar solo in the Liverpool FC team song ‘We Can Do It’, which blasted from the jukebox. Soon everyone was walking round with plastic bags bouncing off the front of their kecks. Most sounds on the jukebox were drowned out by LFC songs, apart from one hilarious five minutes when everyone sang along and did the bump to Joe Tex’s ‘Ain’t Gonna Bump No More With No Big Fat Woman’. There was definitely a few squashed sarnies after that one.

For someone who had to look inconspicuous to bunk a train, Vinnie was as loud as fuck. He turned up in a white Liverpool hat, white T-shirt and white jeans. Peter was right on it. ‘Where’s your paintbrush?’ he said. The choice of outfit seemed even crazier when Vinnie said he was gonna buy a platform ticket then run across the lines and board a Rome special. All’s he had with him was a bag of sarnies and a tenner – no passport, no match ticket and no Italian lire. We didn’t believe him, but he was serious. ‘I don’t care. I’m having a go,’ he said.

By the time we walked over to the Crown on Lime Street, we were all half-gassed. There were just as many people outside the boozer as in it, mostly drinking their own gear. Davey and Eddie Mac from Breck Road passed me a bottle of Strongbow cider. Like a beaut I necked most of it – big mistake! It was the start of one of those phases where a simple trip to the shithouse becomes a major expedition. The occasional flashbacks I get are of me in the Yankee bar rabbiting to a gang of fellas from Park Road. Fuck knows why I went there or how long I was gone, but when I got back to the Crown I couldn’t see the lads. I looked inside: no sign. Star and Garter: no sign. It was no big deal. Getting split up from your mates was a massive and totally accepted part of footy culture then. If ten of you went the game, you’d be lucky to see eight of them till after the match at a prearranged meeting point – usually a pub. That’s why I wasn’t arsed when I couldn’t find them, especially in the atmosphere that was around Lime Street. The word ‘stranger’ doesn’t exist when you’re travelling to your first European Cup final. I had 5000 mates that night. Every bastard was talking to any bastard … you know the score.

We all had an itinerary with designated train numbers and times, but loads were just getting on any. About half eight I walked up past the Punch and Judy cafe with three dead funny lads from Halewood. One of them had a Roman laurel on his head made from privets, and a T-shirt that said ‘Julius Scouser’. There were some great T-shirts knocking about. A few I remember are ‘Tommy Smith is Spartacus’, ‘The Pope is from Gerard Gardens’ and ‘Is Hadrian taking brickies on?’.

The singing inside the station had a Pied Piper effect. I followed it to the side of platform nine, where hundreds were queuing up. I bumped into Vinnie. He told me that our kid and the others thought I’d jumped on a train, so they’d done the same. ‘Your Mick said if I see yer, to tell yer they’ll see yer at Folkestone.’

Vinnie’s platform-ticket plan had gone pear-shaped. Platform tickets were just tuppence each and were for waving goodbye only. He said there were about twenty-five Scousers trying the same thing. They were all smiling and waving to strangers on the London train as it pulled away. ‘They must’ve thought we were all on a day out from the fuckin’ loony bin,’ he said. Bizzies and train guards were well onto it and moved in. There were still a few specials due to leave, but the odds of him bunking on one looked impossible. ‘I’m gonna try the ladder,’ he said, meaning coming in via a fixed metal fire-escape ladder that led into the station from Skelhorne Street – a known bunker’s route that brought you out further down platform nine. His parting words were ‘God loves a trier’, then he passed me his sarnie bag. I watched him go, knowing deep down that he had no chance.

The next half-hour in the queue was heart-pumping stuff. I joined in the singing: ‘Tell me ma, me ma, I don’t want no tea, no tea, we’re goin’ to Italy, tell me ma, me ma’. Adrenalin diluted the ale inside me and replaced it with nervous butterflies. This was it. Five weeks of scrimping, saving, stealing, fiddling and dreaming was within touching distance, and the way I felt at that moment every single second of worry and struggle had been worth it. Passing through those gates onto platforms eight and nine was like being liberated.

I boarded the train and right away bumped into three Kirkby pissheads: Mick and Gilly Stewart and Ged Wainwright. They were all wearing white jeans, which were bang in fashion for the trip; hundreds had them on. Mick pulled a piece of coal out of his jeans pocket … the others did the same. I was snookered till they told me the score. Years ago, during the War, it was tradition for loved ones to pass coal to soldiers before they set off for battle – ‘Keep the home fires burning for a safe return’ – so Mick’s nan had given them a piece each.

It sort of captured the feeling and spirit of the whole thing. It was as if we were all going on a war crusade to some foreign land and the people had come in their droves to see us off. The scenes as we pulled out of Lime Street still give me goosebumps. Bodies and flags waved from every window to the deafening sound of cheers and applause from women, kids and well-wishers in the station. I’ve never felt as proud or as much a part of something in my whole life. It was a touching and unique Scouse send-off.