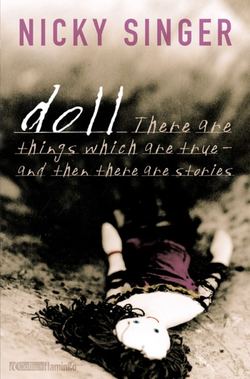

Читать книгу Doll - Nicky Singer - Страница 7

3

ОглавлениеGerda.

This is the name of the doll. It came to me on the bridge, when I was running. Running like I was the wind and the trains were paper.

“Trust me. Trust me, trust me, trust me.” The noise of the wind and the wheels and the wings at my feet. Did she whisper the name to me herself? Or was it my mother’s voice I heard? I don’t know. But the name is right. The name of the child in the Snow Queen. How I loved that story. Had my mother read it over and over again. In those long-ago, happy-ever-after days. How the little girl scoured the world for Kai, the boy with ice in his heart, and how she found him, and held him, and how her tears melted that ice.

And I do trust Gerda. Know that I would follow her to the ends of the earth. Knew it from the moment she uttered that first word: “Come.” Was I waiting for her to speak? It didn’t surprise me. I’ve always believed that love can stretch between worlds. That the dead can speak. That the past stands close enough to whisper in your ear.

“We’re Weavers,” said my mother. “Judith and Tilly Weaver. Weaver by name and weaver by nature. Matilda Weaver. It’s your name but also who and what you are. We Weavers are the weft and the warp, we web things together.”

My father argued with her about that. “You’re only a Weaver by marriage,” he said. “You were born a Barker.” That’s how he crushed her. With small things.

“A name isn’t a small thing,” said Inti. Inti was the molten-eyed Ecuadorian who had the stall next to my mother at the market. “There’s one tribe,” he said, “that never reveal their names to strangers. They believe if a stranger knows your name, he can tramp on your soul.”

And so the day passes in thinking, wandering, wondering, being close. I am content, happy even. I remember how, when I was a small child, I was afraid of the dark. Each night, in order to sleep, I constructed in my imagination fifteen concentric courtyards, each with high stone walls and only one door. And then I walked myself through each one of those doors, locking it behind me. In the innermost courtyard, the fifteenth, was a small square of grass. I bolted the final door, lay down on the grass and slept. Gerda makes me feel as I did in that courtyard. Safe.

So it is a shock to find myself, at dusk, at the glass entrance of the shopping mall. How did we arrive here? Why have we stopped? This is not my place. It belongs to those who thrive in artificial light. It is Mercy’s place. Charlie’s place.

And there they are, the electronic doors swishing open for them. They are coming towards me. Mercedes Van Day and Charlotte Ferguson. Mercy half a step in front. She is captivatingly beautiful. I thought so when she was my friend and I still think so. She’s one of those people from whom you cannot take your eyes. Her skin is flawless, translucent even, as if, beneath the surface, where others have boiling pimples, she has radiant light. I’ve never seen such skin, even on an adult. Her blonde hair swings, impeccably cut, about her face and her eyes are like a cat’s, at once quick and stealthy. They promise you things. Her body is both slim and curved and she has that ability to turn a collar, or hitch a hem so that she looks stylish, individual even in her school uniform. Charlie is larger and darker and drawn to Mercy, as I was, like a moth to a flame.

There is a spring in Mercy’s step. She has made a new purchase. At her side is one of those shining paper carriers with the string handles they give you in designer shops. She will have gone with Charlie for a post-school coffee, and been unable to resist – what? A belt? A skimpy top? A pair of shoes? She smiles and talks and walks towards me.

I’ve tried to walk like that, so the sea of people in front of you parts when you move. I’ve tried to cut my hair so it falls, as hers does, like a kiss against her cheek.

“You are who you are,” said my mother, one foot on the accelerator of her Yamaha Virago 750. “Why try to be someone else?”

“Be yourself,” my mother said, providing me with a non-regulation school jumper. “Why not?”

And of course, I’ve wanted to be as fearless as my mother, as devil-may-care, but not as much as I’ve wanted to be Mercedes Van Day.

They are almost upon me, Mercy and Charlie, but their heads are so close in conversation, they will not see me. I have time to melt away. I choose the bus shelter. I need to be calm, to compose my thinking.

“Inti,” says Gerda. “Concentrate on Inti.”

Inti, my mother’s friend, the gap-toothed South American. Inti, the market man who sold amber and lapis lazuli and opals.

Mercy and Charlie are coming towards the bus stop.

And also panpipes. Inti, who took me on his lap when my mother was busy and told me the names of the Siku, the Latin pipes. Whispered Antara and Malta. Showed me how to fill the bamboo reeds with tiny green seeds. “You have to tune pipes,” Inti said, “in winter. When the pipes are cold, they play too low.”

Mercy and Charlie are going home. They are going by bus. They are taking the bus from this stop.

“Taquiri de Jaine,” says Gerda.

The rhythm of the carnival, Inti’s favourite tune. I try to listen to it. But all I hear is the flip of two plastic seats. Mercy and Charlie sit down. And there I am, in the corner, trapped.

Mercy and Charlie are animated, they talk loudly, excitedly. They are discussing “Celeb Night”. It’s a charity affair, in aid of the NSPCC, and Mercy’s mother is one of the organisers. Come dressed as your favourite star, that was the original idea. It was Mrs Van Day who introduced the idea of a talent contest. “Like they do on the television. Aspiring bands. Singers. A pound if you want to cast a vote.”

Everyone’s going. Mrs Van Day’s promised the press, scouts from the music business. Everyone that is, except me. Why would I want to?

Mercy is going as Britney Spears. She has the body, the smile, the eyes and she’s bought the hair extensions. Now all she needs is a dress.

“Well, actually,” she’s telling Charlie, “I’m going to have trousers and a top. Cindy, you know my mother’s friend Cindy? The dressmaker?”

“Your mother!” exclaims Charlie. “If she wanted a photographer from Hello! she’d have one for a friend.”

“Yeah, well. Cindy’s copying something from a magazine. Something Britney actually wore. It’s gauze mostly. Blue gauze. It’s going to be amazing. Just you wait. Got a fitting on Sunday. Got to look my best, you see.” Mercy pauses. “Jan’s coming.”

“Jan?” queries Charlie.

“Yes. It’s spelt with a J but pronounced like a Y. Yan. Yan Spark. And that’s his real name, not a stage name. How cool is that? Ready-made star quality. But he’s the strong silent type, you see. So I’m going to need more than my sparkling conversation.”

“Is he going in for the contest?”

“Of course. He’s Mr Guitar, apparently. Plays brilliantly, according to his mother who told my mother. But forget guitar, you should take a look at his face. Is he gorgeous or what? His features, Charlie, they’re kind of sculpted. Like he was some Inca god. And his eyes, they’re so dark, so deep you feel like you are looking down a tunnel right into his soul. And …”

And then, with her boy, comes my boy. The one up at the bridge. I’ve felt him tracking me all day, a hound at my back. But I haven’t turned round once to look. Because of his eyes. They are not tunnels you can look down, they are fierce, dark drills. They bore into you. Make you feel that, with a glance, he could pierce your heart right through. Know things about you that even you don’t know.

But I could have stood that. Wouldn’t have cared, except that, at the bridge, he turned those eyes on Gerda. Stared like he could see right through her, too. My Gerda. And I couldn’t bear that again. Stared and stared, as if he had the right. As if he knew something.

I cannot stop my hand, it’s reaching into my pocket. I have to touch her. Put my fingers on Gerda’s warm, white skin. My breath is slamming against the glass of the bus shelter.

This is for you, beloved.

But somehow I fumble. A bus is coming and someone is barging and pushing. It’s an old lady and the handle of her shopping bag is snagged round my arm. I cry out, so as not to drop Gerda. The old woman pulls against me, glares, curses and butts her way on to the bus. I’m still spinning when Mercy says:

“Well, well. If it isn’t Tilly M.”

I come to a stop. We are face to face. Mercy is not getting on the bus. Not this bus anyway.

“Did you bunk off school today to assault senior citizens?”

Charlie sniggers.

I work at composing my features, pay attention to keeping my hand so still she will not see what is clutched at my heart.

“What’s that then?” she asks.

Did I look at Gerda? Did I?

“It’s one of those creepy things her mum makes,” Charlie says.

“Oh,” says Mercy. “A little dolly. Let’s see then.”

A second bus arrives. This has to be their bus. People shuffle and move. Mercy and Charlie don’t move. They stay. The bus drives away. I could run. I could run again. If Mercy touches the doll … If she brings her hand anywhere near …

“I said, let’s see.”

“No!” I jam Gerda into my pocket. And then: “Nothing to see.”

“How old are you, Tilly?” Mercy laughs. And I remember how that laugh used to be full of kindness. How it seemed “quaint” to her that I came to school dressed in non-regulation cardigans and black gym shoes when everyone else had trainers. Mercy was so sure of herself that difference didn’t seem to matter. How I adored her for that. And how bereft I was the day it stopped. The day she came to my house.

“I said, how old are you, Make-Believe?”

Make-Believe. That was my fault too, of course. I wouldn’t tell them my middle name. Mercedes Alice Van Day. Charlotte Elizabeth Ferguson. Matilda M. Weaver. They all had middle names but I didn’t, or not one I was prepared to admit to. Was I afraid they would trample my soul? No. I never shared the secret with Mercy, not even when we were at our closest. The reason was – shame. And, give credit where credit’s due, Mercy never pushed me. Other people did. Small enquiries, a few tentative jokes. But I never cared. What were a few jokes compared with the truth?

It was Charlie who wouldn’t let go. It was how she wormed into Mercy’s affection. How she pushed me away.

“What does the M stand for, Weaver? Go on, tell us. What’s the big deal? Friends are meant to share. Anyway, it’s only a game.”

A Rumpelstiltskin game. What is Tilly’s middle name? Guess, guess, have a good laugh. Tilly Moron, Tilly Misbegotten, Tilly Misery-Guts, Tilly Misfit, Tilly Misnomer and then Tilly Make-Believe.

It was Mercy who coined it.

“Make-Believe,” she said, “it’s Make-Believe, isn’t it?”

And I said yes. To stop the game, but also because it didn’t seem that unkind. There was something innocent in it, something creative, it contained the dust of fairies and of angels. And of course, after that day at my mother’s house, she’d called me many worse things, bitter things. So “Make-Believe” sounded, in my ears, like reconciliation. And I wanted her friendship so much. I wanted her back. How she was, how it all was, before …

“I’m waiting,” says Mercy and she stands, her bus seat twanging upright behind her.

Nothing can happen. This is a bus shelter. A shelter. There are other people here. A second old lady, looking the other way. A mother, fussing over a toddler. Or maybe the toddler’s fussing.

“Are you deaf? As well as infantile? Bet you still have Barbies too.”

“Walk away,” says Gerda.

“I saw you this morning,” Charlie says then. “In Tisbury Road.”

But she can’t have. I looked up and down the street. I looked for her bus.

“That’s where your grandma drops you, when your mum—”

Mum. Not even I called my mother “Mum”. I called her “Mama” because this – along with Weaver – is what she called herself. My father called her “Judith”. Inti called her “Big”. No, I will not have my mother in Charlie’s mouth.

“Leave my mother out of this,” I shout.

“Whoa,” says Mercy. “Steady on.”

“As I was saying,” says Charlie, “your grandma drops you in Tisbury Road when your mother—”

“Shut your mouth. Shut it!” The second old lady tuts and turns to the mother with the toddler. The toddler bursts into tears.

“You’re upsetting the baby now,” says Mercy.

I will not cry.

I will not be angry.

“Mustn’t lose your temper,” says my grandmother. “You have a terrible temper, Tilly. How would it be if we all allowed ourselves to lose our tempers? Self-control. That’s something I learnt from Gerry. My husband never lost his temper.”

“Your mother—” says Charlie.

“Walk away,” says Gerda.

“My mother,” I scream, “is dead. Dead. Dead. Dead!”

“Oh sure,” says Mercy. And she laughs.