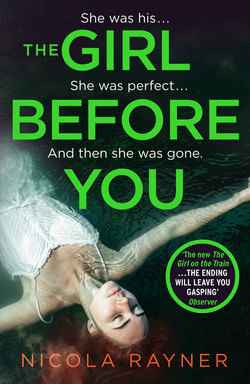

Читать книгу The Girl Before You - Nicola Rayner - Страница 18

Naomi

ОглавлениеIn the mornings our father smelled of aftershave and soap. When we woke, he’d be up already, starting his paperwork downstairs, but his scent lingered in the corridors of the hotel behind him. Our father was tall, with silvering auburn hair. He wore bow ties with his suits so as not to be like other people. It was embarrassing. He also wore leather shoes that clicked on the pavement as he walked.

‘That’s the sound of a real man walking,’ our mother would say. ‘I do like a man with proper leather shoes.’

‘And a bow tie?’ we would ask.

‘Hmm,’ replied our mother.

She always sounded less sure about that.

Our father’s car was an Aston Martin with a personalised number plate, which was the most embarrassing thing of all. The Aston smelled of clean leather seats, as if it were still new. It purred along so close to the ground that we couldn’t see over the hedges. The world looked different through the windows of the Aston. It didn’t win our father many friends.

‘You win some, you lose some,’ our mum said of the car.

She drove a battered but sturdy Volvo without a personalised number plate. In her car, we would sit in the back, pushing our fingers through the guard to touch the dogs’ wet noses. They weren’t allowed near the Aston Martin.

But in the evening, the leather shoes and suit were gone, replaced with corduroys and old jumpers with patches on the elbows. He would do odd jobs in the hotel garden when he could – mow the lawn, build bonfires – and he smelled of wood smoke and beer when he came to kiss us goodnight. The rough texture of his jumper tickled us as we sat up in bed to hug him. He wasn’t the best at bedtime stories – it wasn’t really his thing. Our mother was better, revealing tantalising snippets from Gone with the Wind or acting out the narrative of operas with doll’s house dolls – though not Madama Butterfly (‘it’s too sad’). Our mother had to be careful about things that were sad.

Our dad was good at sums and puzzles. Horses and riding. Dogs. Swinging us high in the air. Long walks on the windy clifftops. Our mother was for tummy aches and baking cakes and singing. She’d sing in the hotel bar on open-mike nights – never for long, just a couple of songs, which she’d murmur into the microphone with her eyes closed, her hair messy from a night’s waiting in the restaurant.

The men in the bar would look at her face carefully then, as if they were looking at the sun. ‘A rare beaut,’ our father used to call her. ‘You’re my rare beaut,’ he would say as he stood behind her in the kitchen and wrapped his arms around her, and she would smile and say, ‘You’re silly. Isn’t your dad silly?’ But she would look flustered, as though she liked it really.

The men who drank in the hotel never really forgave our father for stealing our mother – I think that’s the way they saw it. They called him a spiv. Ruth dared me to ask our mum what it meant and I knew, even as I asked, that it was an ugly word – something we should have looked up in a dictionary rather than saying out loud. Our mother’s fingers touched the corner of her apron, squeezing the material in a ball for a second.

‘Where did you hear that?’

We had heard the word in the bar, from the mouth of Dai the Poet, a camp, overweight man in his fifties, with drama school enunciation and a nasty turn of phrase when he was drunk.

‘What does it mean?’ Ruth asked.

‘It means people are jealous.’ Our mother let go of the apron, brushed it down and looked away.

Of the many things our father was good at, making money was the one that attracted the most attention. It was his gift. He could see opportunities where other people couldn’t; he could crack through the sums; he could glance at the restaurant or the bar and know, more or less, how much they would take that night or what they could do to make more. He had turned our grandmother’s Pembrokeshire hotel from a bohemian labour of love into something profitable in just eighteen months.

‘He came from nothing,’ the posh men would whisper in the bar. Like that was a bad thing: to create something from nothing.

‘He’s not even from here,’ the locals would say. As if that were the final insult: that he had whisked away their most beautiful girl, made heaps of money and, worst of all, he didn’t even have the decency to be Welsh.

The bar was full of tribes – the rich men who’d made their money early in life or inherited and come out to live on the coast; the locals who’d cram the bar on Fridays and Saturdays; or the holidaymakers whose drinking tended not to be bound by which day of the week it was – but our dad didn’t belong to any of them.

Instead, we made a tribe of our own: Ruth and our father with their red hair, my mother and me, with our dark eyes. Neither parent had much tolerance for tales, though we never gave up trying to embroil them both in the ongoing battle of the halfway line, mainly in the car, where it existed as an imaginary border that separated Ruth’s messy side from my neat one.

There were just eighteen months between us. We witnessed the very first moment we met on cine film, a silent movie in muted colours. Ruth, clutching Nunny, her pink toy rabbit, in our grandmother’s arms at the front door, had stretched out to greet our mother as she came back from hospital carrying me in a large white blanket.

‘Baby,’ mouths our mother in the film, tilting my face, peeking through the blanket, towards Ruth.

‘Baby,’ repeats my sister, climbing out of our grandmother’s arms to join me, heedless of the halfway line even then.