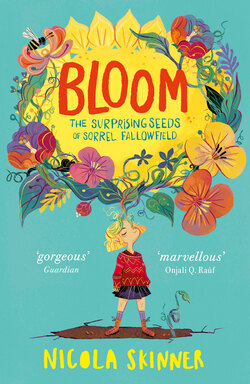

Читать книгу Bloom - Nicola Skinner - Страница 7

Оглавление

WHEN THE NEWSPAPERS and journalists first got hold of my story they wrote a lot of lies. The main ones were:

1. I was the child of a broken home.

2. Mum was a terrible single mother.

3. With a background like mine, it wasn’t any wonder I did what I did.

None of them was true – well, apart from Mum being a single mum. But it wasn’t her fault my dad had done a runner when I was a baby. Yet one of the headlines stuck in my head. I did come from a broken home.

Oh, not in the way they meant it, in the ‘I wore ragged trousers and brushed my teeth with sugar’ sort of way. But our house did feel worn out and broken down – something was always going wrong.

If you’d ever popped in, you’d have felt it too. The tick of the clock in the hallway would follow you around the house like it was tutting at you. The tap in the kitchen would go drip, drip, drip as if it was crying about something. If you sat down in front of the telly, it would lose sound halfway through whatever was on, as if it had gone into a monumental sulk and wasn’t speaking to anyone ever again. Ever.

There was a ring of black mould round the whole bath, our curtains were constantly pinging off their rods in some desperate escape mission and every time we flushed the loo the pipes would moan and groan at what we’d made them swallow. Oh yes, if you visited our house, you’d want to leave within seconds. You’d garble out an excuse, like: ‘Er, just remembered … I promised Mum I was going to hoover the roof today! Gotta go!’ And you’d get away as fast as you could.

Apart from my best friend Neena, not many people stayed long at our home.

And guess what it was called?

Cheery Cottage.

To be honest, though, I didn’t blame anyone that ran away. Because it wasn’t just the damp and the taps and the protesting pipes. It was more than all of that. It was the feeling in the house. And it was everywhere.

A gloomy glumness. A grumpy grimness. A grimy greyness. Cheery Cottage always felt cross and unhappy about something, and there was almost nothing this mood didn’t infect. It inched into everything, from the saggy sofa in the lounge, to the droopy fake fern in the hallway, which always looked as if it was dying of thirst, even though it was plastic.

And – worst of all – this misery sometimes seeped into Mum too. Oh, she’d never say as much, but I’d know. It was in her when she sat at the kitchen table, staring into space. It was in her when she shuffled downstairs in the mornings. I’d look at her. She’d look at me. And in the scary few seconds before she finally smiled, I’d think: It’s spreading.

But what could I do to fix things? I wasn’t a plumber. I was the shortest kid in our year, so I couldn’t reach the curtain poles. When it came to fixing the telly, all I knew was the old Whack and Pray method.

Instead, I had a different solution. And it was to follow this very simple rule:

Be good at school and be good at home, and do what I was told in both.

So, that’s what I did.

I was good at being good.

I was so good, Mum regularly ran out of shoeboxes in which to put my Sensible Child and School Rule Champion certificates.

I was so good, trainee teachers came to me to clear up any questions they had about Grittysnit School rules. Like:

Are pupils allowed to sprint outside?

(Answer: never. A slight jog is allowed if you are in danger – for example, if you are being chased by a bear – and even then, you must obtain written permission twenty-eight days in advance.)

Are you allowed to smile at Mr Grittysnit, our headmaster?

(Answer: never. He prefers a lowered gaze as a mark of respect.)

Has he always been so strict and scary?

(Answer: technically, this is not a question about school rules, but seeing as you’re new, I will let you off, just this once. And yes.)

I was so good, I was Head of Year for the second year running.

I was so good, my nickname at school was Good Girl Sorrel. Well, it had been Good Girl Sorrel, until sometime around the beginning of Year Five when Chrissie Valentini had changed it ever so slightly to ‘Suck-up Sorrel’. But I never told the teachers.

That’s how good I was.

And every time I came home from school with the latest proof, Mum would smile and call me her Good Girl. And that broken feeling would leave her and sneak back into the corners of the house.

For a while.