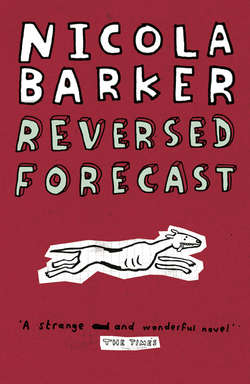

Читать книгу Reversed Forecast / Small Holdings - Nicola Barker - Страница 15

Ten

ОглавлениеRuby awoke to the sound of the telephone ringing. She opened her eyes and tried to pull herself up straight. She’d been slumped over sideways on to her bedside table. Her face felt strange, like warm wax that had set overnight into a distorted, lopsided shape. Her neck ached, even her tongue ached and her body felt, in its entirety, distinctly askew.

Vincent was there. Ugh! She looked at him. A horrible face. Dirty. Phlegm, mucus, special smells. Blood, dried. Everything inside spilling out.

His face was a solid bruise. He was a car accident, still jumbled. She had no clear impression of him. Not mentally, not visually. It was bright in her room, a yellow-white brightness, reflecting unkindly off him.

She sprang out of bed to answer the ringing. She was still wearing her cardigan, which she pulled close around her, and her T-shirt, which she noticed had coffee stains down the front.

The telephone – it had a long extension cord – was situated in the centre of the draining-board next to the sink. She picked up the receiver. ‘Yeah? Ruby here.’

She licked a finger and applied it, somewhat hopelessly, to the stain.

‘You sound rough.’

She didn’t recognize the voice. ‘Hold on.’

She put down the receiver, turned on the cold tap and stuck her head under it, inhaling sharply as the water gushed over her hair, into her ears and down her neck. She turned it off and shook her head, like a dog after a dip, then picked up the receiver again. ‘Hi.’

She felt the water dripping down her back and her face. Eventually a voice said, ‘Hello, Ruby?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Donald Sheldon. Is it too early?’

‘I’ve been up ages,’ she lied. He’d never phoned her before.

He said, ‘Actually, I’d like to see you. This afternoon if it’s possible.’

‘Oh. OK.’

‘There’s a café near Seven Sisters tube.’ He described its precise location. ‘We could meet twelve-ish.’

Twelve was too early.

‘Yeah, that’s fine. Seven Sisters. Twelve-ish.’

‘See you then.’

She put down the receiver and walked into the bathroom to look for a towel. She found one slung over the edge of the bath and wrapped up her dripping hair in it before putting the plug in the bath and turning on the taps.

Back in her bedroom, she rooted out a pair of jeans, a black vest and some clean underwear. Vincent lay across the bed, his legs spread, his feet dangling off the end. His arms, she noticed, now held a pillow over his face. She said, ‘I wouldn’t do that. Someone might be tempted to press down on it.’

He said nothing.

She returned to the bathroom. While she undressed, she debated how soon it would be acceptable to ask him to leave. She tested the water with her hand, climbed in, then lay back and relaxed, staring abstractly beyond her breasts, her knees, her toes, at the taps and the steam from the water.

Vincent felt like a caterpillar changing into a butterfly. That inbetween stage. A pupa. His skin, hard, semi-impervious; himself, inside, withered and formless.

He was not himself. His head bumped and pumped. The light, the morning, scorched him.

During the night he had awoken, he didn’t know what time, and had found a girl, a stranger, next to him. Her hip near his chin. Wool, scratching; cold skin. He had pressed his forehead against her thigh. It had cooled him.

And now it was morning. He needed something. Had to stretch his body – that crumpled thing – his mind, his tongue.

Ruby picked up a bar of soap and started to build up a lather. What does Sheldon want? she wondered. What does he want from me? Her toes curled at the prospect. She stared at them and thought, Why am I doing that with my feet?

Vincent stood on the other side of the bathroom door with his hand on the handle. He shouted, ‘You could’ve told me you were having a bath.’

Ruby dropped the soap and covered her breasts. ‘Don’t you dare come in.’

‘I have no intention of coming in,’ he said scathingly. After a pause he added, ‘Why the hell did you bring me here? I’ve had the worst time.’

She gasped at this, her expression a picture, and shouted, ‘I didn’t bring you here.’

‘Well, I didn’t get here on my own.’

His voice sounded muffled, further away now. ‘Do you always live like this?’

She stood up, indignant, and stepped out of the bath. ‘Like what?’

Silence, then, ‘Forget it.’

‘Like what?’

She grabbed a towel, wrapped it around her and pulled open the door. ‘Live like what?’

He was standing in the kitchen, looking inside one of her cupboards. He glanced at her, in the towel. ‘For a minute there,’ he said, grinning, ‘I thought you were a natural blonde. But it’s only foam.’

She yanked the towel straight. With his cut, his pale, white face, the bruises, the suggestion of a black eye, he looked like Frankenstein’s monster. But he didn’t frighten her. She said calmly, ‘Get out of my flat.’

He grimaced. ‘Some hospitality. I have a migraine and all you can do is shout.’

‘Yeah?’ She smiled. ‘Well, I think you should go.’

She returned to the bathroom, closed the door, dropped her towel.

He said, ‘I have a blotch. I’m going blind. You expect me to go when I can’t even see straight?’

She stared at the bath. ‘Well, whose fault is that?’

She picked up her towel and started to dry herself. She heard the cupboard close.

‘Yours. You shouldn’t have paid my bail.’

She rubbed herself vigorously.

‘And lunch. I only get migraines from gherkins.’

‘What?’

‘An allergy.’

She laughed. She was glad that he had an allergy.

He listened to her laughing. Smiled at it. He liked her flat. It was central. He sat down on the sofa, picked up one of the empty vodka bottles, sniffed the neck of it and winced.

Eventually she emerged, fully dressed, made up, her teeth brushed and her hair gelled.

‘I made you some tea.’ He held out a mug to her.

She took it from him. ‘Aren’t you having any?’

He shook his head. ‘Couldn’t keep it down.’

‘Did you try?’

‘I had some water.’

She sipped the tea. It was luke-warm. ‘How are you feeling?’

He shrugged.

‘What are you going to do?’

He shrugged again.

‘Will you go home? Are you up to it?’

He cleared his throat. ‘May I use your bathroom?’

‘Of course you can.’

Once he’d closed the door she shouted, ‘I’m going out in a minute. Should I trust you here alone?’

‘I wouldn’t.’

She put down her mug of tea. ‘Only a trustworthy person would’ve said that.’

Think what you like.’

‘I will.’

She picked up her keys. She was insured. She needed a new stereo, anyway.

Donald Sheldon – self-appointed king of Hackney Wick – was a short, squat man with thick, wavy hair and skin the colour of roasted peanuts. He was drinking a foamy coffee and wore an expensive business suit. Ruby was nervous, had thought too much about meeting him.

‘Am I late?’

He shrugged. ‘Ten minutes. Coffee?’

She nodded. ‘Thanks.’

He maneuvered himself out from behind the table and strolled over to the counter. Ruby watched him. She regularly saw him down at the track. He trained mainly at Hackney, but she was well informed that he ran his dogs wherever he could. She’d often seen him interviewed on SIS, the racing channel.

He returned to the table, carrying her coffee, holding on to its saucer. She looked down at his hands and saw that he wore rings on most fingers but none that seemed like a wedding ring. He sat down again. ‘I’ve seen you at Hackney a lot. You obviously enjoy the sport.’

She nodded.

‘How old do you think I am?’

This question surprised her. She stared at his face, his thick hair, his good tan. She wanted to flatter him. ‘Forty, forty-two.’

He smiled. ‘Forty-eight. I’ve been racing dogs since I was fourteen.’

‘Thirty-four years.’

‘I first went to Hackney when I was five, with my dad. You might get to meet him later.’

She stared at him, bemused, wondering where his dad fitted into the equation.

He smiled fondly, but more to himself than at her. ‘My dad got me my first dog. He helped pay for it by putting his every last penny on Pigalle Wonder in the 1958 London Cup. A great champion: big, but well balanced. Really handsome.’

Ruby put her teaspoon in her coffee and stirred away some of the foam. She felt obliged to say something but couldn’t think what, so she just said, ‘Betting on the dogs is a bit of a lottery.’

Don looked irritated. ‘I tell you, the only important thing you need to do to win at the dogs, Ruby, is to rely on honest thinking.’

She liked the way he’d used her name. She looked into his face. Did he want to employ her or to fuck her? Either way, she was flattered. He was saying, ‘Racing isn’t just about speed.’

He paused. ‘Do you know what it is that makes a good dog?’

Ruby focused on her coffee and tried to think. Eventually she said, ‘Speed and intelligence, mainly.’

He shook his head. ‘Racing is all about negotiating bends. To negotiate a bend you need balance, coordination and muscular control. But it’s more than that. A dog must have the will to win. It has to have that primitive urge. Some dogs will always be chasers or chuckers. A dog must know how to place itself. It’s got to be crafty.’

She looked at his hands as he spoke. Brown, clean hands. What did he want? What was he doing?

He said, ‘I didn’t know anything when I got my first dog.’

An image shot into her mind of how Donald Sheldon would look naked. She visualized him with an all-over tan and pinky-brown genitals. Not too much body hair. His stomach, slightly saggy, and his breasts.

He said, ‘All this is leading somewhere.’

‘Is it?’

Of course. He looked at her, grinned, then said, ‘And I think I have a good idea where you want it to lead.’

His voice sounded suggestive, arrogant, even sensual. He was old. Not that old. She inhaled deeply and stared straight into his eyes. He picked up a fork and shook it for emphasis, ‘I’m willing to sell you that dog.’

‘Dog?’

The one we discussed.’

‘Discussed?’ Ruby wanted to rewind this conversation in order to try to make sense of it.

He dropped the fork, laced his fingers together and leaned forward. ‘She’s trained. She’s in good form. I mean, she’s out of season now and she’s in good nick. She’s registered. She has a race or two lined up at Hackney, but after that it’d be your business.’

He was trying to sell her something! Donald Sheldon!

I would never, she thought, holding in her gut, I would never have had sex with him. Never.

He added, ‘It must be about her fourteenth week since she was in season. She’s probably got a bit rusty while she was rested, but that’s only natural.’

Ruby tried desperately to remember what she had said to him, how this situation had developed. Had he confused her with someone else? I didn’t even want a job, she thought furiously. Not that kind of job.

He frowned. ‘She’s put on weight, but bitches often do, even if they haven’t been mated. Her current grading figure isn’t very encouraging, but I’d be giving her to you for nine hundred.’

She said carefully, ‘To be honest, cash-flow is a bit of a problem for me at the moment.’

She wanted to laugh in his face. It was all so stupid.

He shrugged. ‘I wouldn’t want the money straight off. A week would do. Six days. If we shook on it now you could take her immediately.’

He was squinting with sincerity. He sincerely thought he was doing her a favour. If he’d employed her, if he’d fucked her, he would’ve worn that same expression. But he was selling her something.

Selling her something.

She had to admire him.

He waited.

It was her turn. To do. What?

She took the easiest option, as was her nature.

She nodded and shook his hand. His skin was warm and dry.

He stood up. ‘The dog’s down at the kennels. Here …’ He handed her his card, which she took and inspected.

‘My dad’ll be there for most of the afternoon. He’s expecting you.’

‘Thanks.’

I’m not doing you any favours. I’ve had very little luck with this particular bitch. But you expressed an interest and now she’s yours.’

Ruby tried to smile as she placed his card in the front pocket of her jeans. He turned to go. She watched him as he walked between the tables and up to the door. He pushed it, it swung outwards and he stepped outside.

She raised her eyes to the ceiling and noticed a large fan up there, turning rapidly.

Which particular bitch? When had she spoken to him at the track? Had he been holding a dog at the time? Had she been holding one? Had she expressed an interest?

She felt hot. The fan’s rapid movements were making her feel queasy. She pulled off her jacket and walked outside. It was hot here too. Things were fuzzy. She blinked, unable to tell whether this fuzziness was caused by heat, a heat-wave shimmering on the Sunday roads, or by movements behind her eyes, inside her.

Vincent pottered around the flat, feeling no particular urge to leave. He tried to assess Ruby on the basis of her personal possessions, but there was little of interest to look at apart from her record collection and her underwear. The record collection was impressive.

His headache was now a dumb whine at the back of his skull, but tolerable. He found an old Kraftwerk album and put it on – turning down the volume slightly – then wandered about, acclimatizing, inspecting things.

He had a bath. It felt like ages since he’d had a proper wash. He picked up Ruby’s soap and sniffed it. It wasn’t strongly perfumed – smelled like Palmolive – so he used it freely, grinning to himself, imagining which parts of Ruby’s body it had lathered. The warmth of the water, the rubbing, the foam, gave him a slight erection. He stared at it for a while with a terse and serious expression, then burst out laughing. It bobbed down in the water, submissive again, mournful and flaccid.

After drying himself, he went into the kitchen, still naked, did the washing up and then returned to the bathroom, where he picked up his clothes, dressed and surveyed himself in the mirror. His whole forehead was a pinky-purple colour. This bruising reached down to either side of his eyes. One eye was black. He inspected the cut more thoroughly. Most of the bump had gone down, but several strands of hair were caught inside the mouth of the gash. He pulled at them, very gently, wincing as some of them came out. He pulled a few more and then gave up, concerned that he might bring back his headache.

He returned to the kitchen and inspected the cupboards to see what food Ruby had in. Tinned stuff, dried stuff. He’d cook something.

While some beans were soaking he tidied up the living-room and then moved into Ruby’s bedroom. Her carpet was knee-deep in pieces of clothing. He kicked these into a large pile and then sorted out what was clean and what was dirty. He sniffed, looked, fondled.

He liked it here. He’d stay for a while, but he wouldn’t ask. If you asked, people said no. Even soft people. Eventually.

Ruby pressed the buzzer and listened out for barking, but could hear none. The building was a mixture of grandeur and delapidation. It was built in a square around a tarmacked courtyard. The entrance was barred by a large, black, metal gate.

After several minutes a tiny old man staggered across the courtyard towards her. He looked like Mr Punch, all nose and chin with eyes like sultanas. He reached the gate, puffed out, and gazed through it at her. ‘You’ve come to get the bitch?’

Ruby nodded and said, ‘I’ve seen you at Hackney before, haven’t I?’

‘Could’ve, but I’m usually at Walthamstow.’

He started to unlock the gate before adding, ‘That bitch of yours wouldn’t run on the Walthamstow track for love nor bloody money. They’ve got a McGee hare there. You familiar with it?’

Ruby frowned. ‘It’s smaller, isn’t it?’

‘Smaller than the Outside Sumner and doesn’t make so much noise. Stupid bitch wouldn’t run for it. Trap opened and she didn’t come out. Nice grass track but she wouldn’t have any of it.’ He shook his head. ‘Racing manager was about ready to kill me. Punters weren’t happy either. There again, she was still a novice, so she probably only had about fifty quid on her.’

He pulled the gate open. Ruby stepped inside and he closed it behind her, then turned and led the way across the tarmac. She followed him, watching the back of his yellowy kennel coat, into the main building, through an unprepossessing passageway, which smelled of detergent and dog, and into a large, square, brightly lit kitchen.

He pointed towards the big pine table that filled the centre of the room. ‘Sit down while I go get her. I’ll bring her registration booklet too.’

Ruby sat down and rested her elbows on the table. The room felt airless, she felt aimless. Why was she here? She thought, I won’t think anything. Not anything. Nothing.

When he returned, she said, ‘Don didn’t get around to telling me your name.’

He grinned. False teeth. As straight as a die. ‘Stanley. Stan. I’m seventy-four and he still has me working a seven-day week.’

Ruby pushed herself back on her chair and peered over at the dog. Stan was holding a lead and the bitch stood at the end of it, looking tense. She couldn’t help thinking how large the animal seemed. Not fat, just big.

Stan leaned against the table and got his breath back. The dog stood still, not pulling on her leash, but managing to look on edge, padding from foot to foot. He stared down at her. ‘I like black bitches. This one’s related to Dolores Rocket. Won the Derby. Won the Puppy Oaks too, twenty-odd years ago.’

He jerked the lead and brought the dog’s head up. Her face was skinny, scraggy and strangely petulant.

‘I’ll get a muzzle on her.’

‘Do you have to?’

‘She’ll chase anything if she feels the urge.’

‘Anything but the McGee hare, eh?’

Stan fitted the muzzle over the dog’s face. ‘Well, they’ve all got coursing in their blood, but these dogs …’ He slapped her lightly on her rump and she stiffened her legs to take the slap. These dogs were bred from strains of dogs that didn’t so much care what they chased, they’d run for anything.’

He brought the bitch around the table and handed Ruby her lead. Ruby hesitated and then took it. She felt a dart of terror in her chest that started between her breasts and shot up to her throat. She tried to swallow it, to keep it under.

Stan looked down at her for a moment, then said conspiratorially, ‘How much is he asking for?’

Ruby felt the leather of the lead between her finger and her thumb. ‘Nine hundred.’ When she said it, it meant nothing.

He burst out laughing. ‘I’ll tell him you’ll give him seven. He had her down at Swaffham in Norfolk on Friday. Check her toes.’

Ruby picked up the dog’s right foot. The pads all seemed fine. She picked up the left and he interrupted her, taking hold of the paw himself and parting the front pads. ‘Third pad’s slightly swollen.’

‘Is that a problem?’

She knew it was. I know all this, she thought, I know this stuff.

‘I’ll tell Don you thought it was.’

She smiled gratefully and stroked the dog’s back. ‘How did she do at Swaffham? I didn’t even know Don raced in that part of the country.’

‘How do you think she did?’

He passed Ruby the registration booklet. She opened it. Little Buttercup. Black bitch … When she was born, where, the names of her parents, the size of the litter. Physical description. Tiny details. Times of her races, places. Swaffham – the latest entry.

‘Sixth.’

‘She’s got a race lined up at Hackney on Thursday. You’d better have a chat with the racing manager, though. He’s not happy with this bitch. Did Don tell you she’s in the E grade? Her actual running time at 525 yards was 30.40 on her last night out.’

Ruby verified this in the booklet. It wasn’t a good time.

‘Just the same,’ he added, noting her expression, ‘there’s nothing wrong with her physically. The toe’s no problem. You’ve obviously got a good eye. She’s a fine-looking bitch.’

Suddenly, at last, she remembered. A month ago, Hackney Wick, the traps were loaded. Six dogs. The hare, starting, the squeal of it. Some dogs, barking, whining. And then. She remembered it. Her trap. Number six. A tail, sticking out through the bars at the front.

‘She turned around!’ Ruby said. ‘In the trap. She turned around in the trap, and I thought …’ Ruby had thought, That’s only logical. She turned around because that’s the direction the hare’s coming from. And Don was furious. He said… and I said … and he said … and I said, ‘But she’s a fine-looking bitch.’

Stan was staring at her, nervously.

‘Sorry,’ she said, almost laughing with relief, ‘I just thought of something.’

‘Don didn’t say what you were planning to do with her.’

‘I don’t know. He said she had a couple of races lined up.’

‘One race on Thursday.’

Ruby was thinking now, planning. ‘I’d better get a licence.’

He stared at her blankly. ‘She’s not your only dog?’

‘My first.’ She liked this idea. She’d been sloppy, before, admittedly.

‘Have you got kennels?’

‘No.’ She said this with great certainty, as though only saying it this way would mean it didn’t matter.

‘You won’t get a licence then. Not without proper kennels. Anyway, when the racing manager at Hackney finds out Don isn’t training her any more, he’ll drop her from the card. If she doesn’t get a place in her next race, he’ll drop her for the season anyway.’

Ruby stared at the dog. The dog’s expression was docile but furtive.

‘You,’ she said, with sudden fondness.

The dog licked her lips. Her whiskers stuck out of her cheeks – silver against her black fur – like needles in a pincushion.

After a while Ruby said, ‘There’s no law against being too keen.’

‘There should be, though.’

Stan leaned against the table. ‘You could run her at an independent track and you wouldn’t even need a licence. Swaffham’s a permit track. You could run her there for fifty quid. Or you could even breed from her.’

‘I could,’ she said. ‘I could, but I don’t want to.’ She was making decisions now. She could make them. ‘I want to run her at Hackney.’

‘You can’t.’

‘I can run her on Thursday.’

‘He’ll drop her if he finds out Don’s sold her.’

‘What if she got a place?’

He laughed. ‘She won’t.’

‘But what if she did?’

‘He’ll drop her anyway.’

‘She deserves a chance.’

Stan thought about this, looked unconvinced, but said, ‘If I come down on the day, and anyone asks, you can say you’re with me.’

Ruby smiled. ‘I’ve got plans for her.’

Stan stuck his hands deep into his pockets. ‘You’ll find out soon enough she’s got plans of her own.’

Vincent scowled at the dog. ‘Where did that come from?’

Ruby closed the door behind her and unclipped Buttercup’s lead from her collar.

‘She’s a bitch. I just bought her.’

‘Why?’

She sat down. ‘I don’t know.’

He stared at the dog as she walked around the room, sniffing furniture and poking her nose into corners.

‘Black’s a good colour. She matches everything,’ he said.

‘Yeah. I really needed to hear that.’

‘I made dinner.’

‘I thought you’d be gone.’

‘Sorry to disappoint you.’

He went into the kitchen and dished up the food he’d prepared.

‘Don’t give any to the dog.’

‘I wasn’t planning to.’

‘She’s on a diet.’

Ruby took the plate he handed her and started eating. Tuna, rice, sweetcorn, beans. The dog smelled the food and walked over. She sat next to Ruby, staring at the plate, her tail making a slight swishing sound against the carpet.

‘Does she bite?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Why’s she wearing that muzzle?’

Ruby closed her eyes, stopped chewing and swallowed. ‘At Tottenham Court Road tube she chased a woman wearing a furtrimmed jacket up the escalator.’

He laughed. ‘Did she get her?’

‘She caught her but she didn’t bite her. She was wearing her muzzle.’

‘You should’ve had her on a lead.’

Ruby dropped her fork and showed him her hand. ‘Leather burns.’

She continued eating. This is nice.’

‘I trained as a chef. In Dublin. They had a big dog track there. Shelbourne Park. I went once but I never won a penny.’

‘There are always plenty of jobs for chefs up west. Imagine what you could earn. You could pay me back in no time.’

‘I don’t think so.’

He stood up and went to turn over the record he’d been listening to earlier, then ran some water into a pan and put it down on the floor for the dog.

‘Can she drink through that muzzle?’

‘Yeah.’

He returned to the sofa, noting Ruby’s miserable expression. ‘I get the feeling you didn’t really think this through.’

‘Story of my life.’

She continued eating, then added, ‘But there was a great moment back then when it really did seem like a good idea.’

‘She’ll chew this flat to pieces.’

‘I’ll keep her muzzled.’

‘What will you do with her when you’re at work?’

The dog, suddenly, inexplicably, started to bark. Vincent jumped and dropped a forkful of rice on to his lap. He scooped it up with his fingers and crammed it into his mouth. Ruby craned her neck and stared over the back of the sofa towards Buttercup, who was still standing next to her bowl of water.

‘What’s up?’

She called out her name but the dog didn’t respond, so she put down her plate and walked over to her, squatted down next to her and tried to attract her attention. The dog continued to bark, loudly, bouncing forward on her front paws. Ruby tried to force her to sit by pushing down her rump but the dog wouldn’t oblige. She tried talking sternly and then, finally, shouting.

Vincent put down his plate and walked over. ‘What’s she barking at?’

‘I don’t know. She was fine when she came in.’

The dog fell silent. They both stared at her, surprised. Then, after a five-second hiatus, she started up again.

Ruby swore.

‘If the bloody neighbours find out I’ve got a dog, I’ll be evicted.’

‘Follow her eyes.’

‘Why?’

She peered into Buttercup’s face. The dog’s eyes were glazed and purposeful. Her breath was bad.

Vincent bounded over to the stereo and lifted the stylus. The dog stopped barking. He dropped it again. She barked.

‘She doesn’t like Kraftwerk, so she’s barking at the speakers.’

He squatted down, took the record off and threw it on the floor, then put another one on.

Ruby’s eyes widened. ‘Be careful. You’ll scratch them.’

He turned the volume up and waited for a song to start. As soon as it did, so did the dog. He laughed and switched it off. ‘She doesn’t like Inner City either.’

He took out a Ray Charles album and slung it on. It began to play. The dog cocked her head, listened intently and then sat down.

‘Look at her! She’s an old crooner.’

He was preparing to change the record yet again when Ruby crawled over to the socket in the wall and pulled out the plug. She glared at him, still on her hands and knees. ‘If you’ve scratched any of my records you can pay me for them.’

‘I won’t scratch them.’

‘I bet you already have.’

He picked up one and inspected the vinyl. Ruby squatted down next to the dog and stroked her. She said, ‘She’s all upset. Her heart’s beating like crazy.’ After a few seconds she added, ‘You can tell everything you need to know about a dog’s condition when you stroke it. She’s got strong, wide shoulders, a good, firm back …’

I’ll get him to stay, she thought, at least for tomorrow. He can look after her while I’m out, until she gets used to this place. He can take her to Hyde Park.

She continued to stroke the dog, who rested her chin on the carpet and closed her eyes.

Vincent watched this. He realized something. They wouldn’t get around to sex now. That’s what the dog meant. He hadn’t really considered sex, planned it, wanted it. Even so.

He snapped the record he was holding in half. It was a sharp, clean break. They both stared at him: Ruby, the dog.

‘You’re going to replace that record.’

He smiled. Of course he would. He studied the two halves to see what it was.

Ruby picked up the dog’s lead and attached it to her collar.

‘Where are you going? You haven’t finished eating yet.’

She ignored him, pulled on her jacket, checked for her keys and then opened the door. He was a bastard. She wanted to punch him. She stepped out into the hallway, the dog at her heels.

He stood up. ‘If anywhere’s open,’ he shouted after her, ‘You’re completely out of milk.’