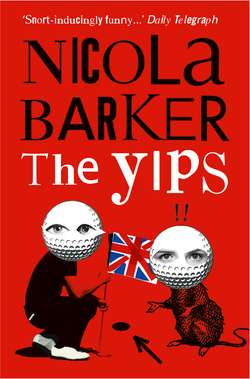

Читать книгу The Yips - Nicola Barker - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Ransom rolls on to his back, yawns, stretches out his legs and farts, luxuriously. He feels good. No. No. Scratch that. He feels great. And he smells coffee. The golfer flares his nostrils and inhales deeply. Coffee! He loves coffee! He wiggles his toes, excitedly, then frowns. His feet appear to be protruding – Alice in Wonderland-style – from the end of his bed. He puts a hand above his head (thinking he might’ve inadvertently slipped down) and his hand smacks into a wooden headboard.

Ow!

He opens a furtive eye and gazes up at the ceiling. He double-blinks. He is in a tiny room. It is a pink room, and it is a smaller room than any room he can ever remember inhabiting previously. A broom cupboard with a window. Yes. And it is pink. And the bed is very small. He is covered with a duvet, a pink duvet, and the duvet has – his sleep-addled eyes struggle to focus – pink ponies on it! Little pink ponies, dancing around! The duvet is tiny – ludicrously small, like a joke. A laughably tiny duvet. A trick duvet. A miniature duvet. He tries to adjust it but he feels like he’s adjusting some kind of baby throw. A dog blanket. When he moves it one way, a different part of his body protrudes on the other side. His body (he is forced to observe) is not looking at its best. His body looks very big. His body looks coarse and capacious in this tiny, dainty, girly, pink room. His body looks hairy. It feels voluminous.

He shuts his eyes again. He suddenly has a headache. He thinks about the coffee. He can definitely smell coffee. He needs a coffee. He opens his eyes, turns his head and peers off to his right. (Might there be a door to this room so that he can eventually get –)

WHAH!

Ransom yelps, startled, snatching at the duvet. Two women – complete strangers! – are standing by the bed and staring down at him, inquisitively. Not two women. No. Not …

A woman and a girl. Yes. But the woman isn’t a woman, she is a priest (in her black shirt and dog collar), and the girl isn’t a girl, she’s … What is she? He inspects the girl, horrified. She’s half a girl. The lower section of her face is … It’s missing. A catastrophe. It’s gone walkabout. Or if not quite missing, exactly, then … uh … a work in progress. A mess of wire and scar and scaffolding.

The girl registers his disquiet and quickly covers her jaw with her hand. Ransom immediately switches his gaze back to the priest again, embarrassed.

‘Thank goodness he’s finally awake,’ the priest murmurs, relieved.

The half-faced girl nods, emphatically. She is wearing a school uniform. Her hair is in two, neat plaits.

‘I don’t recognize him,’ she whispers, from behind her hand. ‘Dad said he was really famous, but I don’t recognize him at all.’

It takes a while for Ransom to fully decipher her jumbled speech, and when he finally succeeds he feels an odd combination of satisfaction and disgruntlement.

‘Ssshh!’ the priest cautions her.

‘Where am I?’ Ransom croaks, trying to lift his head.

‘You’re in my bedroom,’ the girl promptly answers.

‘I left you to lie in for as long as I could,’ the priest tells him (rather brusquely, Ransom feels). ‘Gene left for work several hours ago. But Mallory needs to go to school and I’m scheduled to meet the bishop in Northampton at ten …’ She checks the time. ‘I don’t have the slightest clue where Stan is right now, so …’

She shrugs.

‘Oh.’

Ransom feels overwhelmed by an excess of information.

‘I like your feet.’ The girl chuckles, pointing.

After a short period of deciphering, Ransom peers down at his feet. He can see nothing particularly remarkable or amusing about them.

‘Thanks,’ he says, just the same, and then slips a hand under the duvet to check he’s still decent (he is – just about).

‘Your clothes are folded up on the stool,’ the priest says, pointing to a pile of clothes folded up on a pink stool.

‘I folded them,’ the girl says.

Ransom lightly touches his head. He suddenly feels a little dizzy. And he feels huge. It’s a strange feeling. Because it’s not just his actual, physical size, it’s also his … it’s … it’s …

‘I suddenly feel a bit …’

‘Nauseous?’ the priest fills in, anxiously. ‘There’s a bucket next to the bed if you’re …’

‘If he’s sick in my bed I’ll just die!’ the girl exclaims.

‘… big,’ Ransom finally concludes. ‘I suddenly feel very … very big. Very large.’

He pauses. ‘And conspicuous,’ he adds, ‘and vulnerable.’ He shudders (impressing himself inordinately with how frank and brave and articulate he’s being).

Nobody says anything. They just stare down at him again, silently.

‘I’ve brought you some coffee,’ the woman eventually mutters. She proffers him a cup.

‘If he’s sick in my bed I’ll just die!’ the girl repeats, still more emphatically.

‘I feel like I’m trapped inside this weird, fish-eye lens,’ Ransom continues, holding out his hands in front of his face and wiggling his fingers, ‘like I’m –’

‘There should be a little water left in the boiler,’ the priest interrupts him, ‘enough for a quick shower. You can use the pink towel. It’s clean. And you can help yourself to some cereal, but I’m afraid we’re all out of –’

‘Not the pink towel, Mum!’ Mallory whispers, imploringly. ‘Not my towel!’

‘It’s the only clean towel we’ve got,’ the priest explains. ‘I haven’t had time to do the –’

‘But it’s –’

‘Enough, Mallory!’ the priest reprimands her, pushing the coffee cup into Ransom’s outstretched hands. ‘You’re already late for school. Did you pack up your lunch yet?’

The girl slowly shakes her head.

‘Well hadn’t you better go and do it, then?’

They turn for the door.

‘I won’t use the pink towel,’ Ransom pipes up.

The priest glances over her shoulder at him, irritably.

‘I won’t have a shower,’ Ransom says, intimidated (she is intimidating). ‘I can always have one when I get back to the hotel.’

‘Fine.’ She shrugs. ‘But if you do decide to …’

‘I won’t,’ he insists. ‘So don’t fret,’ he yells after the girl. ‘Your towel is safe.’

He carefully props himself up on to his elbow and takes a quick sip of his coffee, then winces (it’s instant – bad instant).

‘Where am I, exactly?’ he asks, but nobody’s listening. They’ve already left him.

‘Where am I, exactly?’ he asks again, more ruminatively this time, pretending – as a matter of pride – that he was only ever really posing this question – and in a purely metaphysical sense, of course – to himself.

* * *

Gene knocks on the door and then waits. After a few seconds he inspects his watch, grimaces, knocks again, then stares, blankly, at the decorative panes of stained glass inside the door’s three, main panels. In his hands he holds the essential tools of his trade: a small mirror (hidden within a slightly dented metal powder compact, long denuded of its powder), a miniature torch (bottle green in colour, the type a film critic might use) and a clipboard (with his plastic, identification badge pinned on to the front of it).

No answer.

He studies his watch again, frowning. He knocks at the door for a third time, slightly harder, and realizes, as he does so, that the door isn’t actually shut, just loosely pulled to.

He scowls, cocks his head and listens. He thinks he can hear the buzz of an electric razor emerging from inside. He pushes the door ajar and pops his head through the gap.

‘Hello?’ he calls.

No answer. Still the hum of the razor.

‘HELLO?’ Gene repeats, even louder. ‘Is anybody home?’

The razor is turned off for a moment.

‘Upstairs!’ a voice yells back (a female voice, an emphatic voice). ‘In the bathroom!’

Gene frowns. He pushes the door wider. The razor starts up again.

‘HELLO?’

The razor is turned off again (with a sharp tut).

‘The bathroom!’ the voice repeats, even more emphatically. ‘Upstairs!’

The razor is turned on again.

Gene gingerly steps into the hallway. He closes the door behind him. The hallway is long and thin with the original – heavily cracked – blue and brown ceramic tiles on the floor. There are two doors leading off from it (one directly to his left and one at the far end of the corridor, beyond the stairway. Both are currently closed, although the buzz of the razor appears to be emerging from the door that’s further off).

The stairs lie directly ahead of him. Gene hesitates for a moment and then moves towards them. At the foot of the stairs is a small cupboard. He has already visited seven similar properties on this particular road and he knows for a fact that in all seven of the aforementioned properties the electricity meter is comfortably stored inside this neat, custom-made aperture. Gene pauses, stares at the cupboard, then reaches out a tentative hand towards it.

His fingers are just about to grip the handle when –

‘UPSTAIRS!’

The woman yells.

Gene quickly withdraws his hand. He sighs. He shakes his head. He gazes up the stairs, with a measure of foreboding.

‘THE BATHROOM!’ the voice re-emphasizes, quite urgently. ‘QUICK!’

Gene starts climbing the stairs. Sitting on the landing at the top of the stairs is a large, long-haired tabby cat which coolly appraises his grudging ascent. When he reaches the landing it turns and darts off, ears pricked, tail high, jinking a sharp left into an adjacent room which – from the particular quality of the light flowing from it – Gene takes to be the bathroom. Gene follows the cat into this room and then draws to a sharp halt.

The bathroom (his hunch proved correct) is crammed full of cats. Five cats, to be exact. One cat is perched on the windowsill (the window is slightly ajar) and it takes fright on his entering (leaping to its feet, hackles rising, hissing), then squeezes through the gap and promptly disappears. Three others – with rather more sanguine dispositions – are arranged on the worn linoleum in a polite semicircle around the edge of the bath. The fifth cat – and the boldest – is sitting on the corner of the bath itself, closest to the taps.

The bath – an old bath, long and narrow, with heavily chipped enamel – is currently full of water. Next to the bath (and the cats) is an old, metal watering can which Gene inadvertently kicks on first entering. He exclaims as his toe makes contact, but it isn’t so much the can (or his clumsiness) that he’s exclaiming at. He is exclaiming – with a mixture of surprise and consternation – at the rat.

There is a rat in the bath – a large, brown rat – doggy-paddling aimlessly around. Gene bends down and slowly adjusts the watering can, his eyes glued to the rodent.

It is huge – at least twelve inches in length (excluding the tail) – and it is plainly exhausted. As Gene quietly watches, it suddenly stops swimming and tries to stand up, but the water is too deep. It goes under for a second, panics, and then returns to the surface again, spluttering.

Gene is no great fan of rats – or of rodents, in general – yet he can’t help but feel moved by this particular one’s predicament.

‘I suppose I’d better get you out of there, eh?’ he mutters, popping the torch between his teeth, transferring the powder compact into the hand with the clipboard, reaching down and calmly grabbing its tail.

The rat is heavier than he anticipated as it exits the water. He observes (from its prodigious testicles) that it is male. ‘How long’ve you been in there, huh?’ Gene chuckles, through clenched teeth, as it jerks and swings through the air, legs scrabbling, frantic to escape.

The cats all commence padding around below it. Two rise on to their back haunches, paws tentatively raised.

‘Sod off!’ Gene knees a cat out of the way and lifts the rat higher, suddenly rather protective of it. The rat gives up its struggle, relaxes and just hangs there, limply.

‘Very sensible,’ Gene commends it. He peers around the bathroom (to check there’s nothing left in there to detain him), then slowly processes downstairs carrying the rat, gingerly, ahead of him (followed by a furry, feline train).

He pauses for a second in the hallway, unsure of what to do next. He decides (spurred on by the sound of voices) to consult with the opinionated female on this issue – presumably the home-owner – and so pads down the corridor.

It is difficult for him to knock (or to speak, for that matter, with the torch still gripped between his teeth) so he simply bangs on the door with his elbow and shoves it open with his shoulder.

He is not entirely prepared for the sight that greets him. He blinks. The room is cream-coloured – cream walls, cream blinds, imbued with an almost surgical atmosphere – and flooded with artificial light. A crouching woman with red lips and quiffed, auburn hair (tied up, forces’ sweetheart-style, in a neatly knotted, polka-dotted scarf), gasps as he enters. Another woman – dark-haired, semi-naked, her back to him (thank heaven for small mercies!) – propped up on a special, padded bench, is inspecting her own genitals in a small, hand-held mirror, as the first woman (the gasping woman) shines a tiny torch into the requisite area. The rat begins to struggle.

Gene immediately backs out of the room, horrified. The door swings shut on its hinges. He retreats down the corridor, hearing an excitable discussion taking place inside (crowned by several, muttered apologies, then rapid footsteps). The door opens. The auburn-haired woman stands before him. She is wearing a white, plastic, disposable apron and matching disposable gloves. She is still holding the torch. She seems furious, then terrified (on seeing the rat, close at hand) then furious again.

He notices that her auburn hair is quaintly pin-curled underneath the scarf (which reminds him – with a sudden, painful stab of emotion – of his beloved late grandmother, who once used to curl her hair in exactly this manner). The woman is slight but curvaceous (the kind of girl who at one time might’ve been lovingly etched on to the nose of a spitfire) with a sweet, heart-shaped face (he sees a sprinkling of light freckles under her make-up), two perfectly angular, black eyebrows and a pair of wide, dark blue eyes, the top lids of which are painstakingly liquid-linered. Her lips are a deep, poppy red, although her lipstick – he notes, fascinated – is slightly smudged at one corner.

‘Who are you?’ she demands, flapping her hands at him to move him further on down the hallway. ‘What on earth d’you think you’re doing?’

‘I’ve come to read the …’

Gene lifts the clipboard, trying not to trip up over the cats, his speech (through the torch) somewhat slurred. Both parties notice, at the same moment, that their torches are identical.

‘I should probably …’ He lifts the struggling rat.

The woman darts past him (he registers the solid sound of her heels on the tiles), yanks the door open and shoves him outside. Gene drops the rat into the tiny, paved, front garden and it immediately seeks shelter behind a group of bins.

‘I thought you were my brother!’ the woman exclaims.

Gene spits out his torch. ‘I came to read your meter,’ he stutters, ‘but the door was ajar and when I …’

A phone commences ringing in the hallway behind her. It has an old-fashioned ring. It is an old-fashioned phone: black, square, Bakelite, perched on a tall, walnut table, just along from a large aspidistra in a jardinière. Gene frowns. He has no recollection of noticing either the phone or the plant on first entering the hallway a short while earlier.

The woman turns to inspect the phone, then turns back to face him again.

‘Stay there,’ she mutters, glowering. ‘I should answer that.’

She slams the door shut.

Gene waits on the step as a brief conversation takes place inside. He glances around him, looking for the rat. He inspects his watch again. He dries his torch on his shirt-front. The door opens.

‘It was just a bit of a shock …’ the woman explains, calmer now.

‘Of course.’ Gene grimaces. ‘I really should have knocked. I just –’

‘We have the same torch,’ she interrupts him, pointing.

‘Yes.’ Gene nods.

‘Mine’s a little unreliable,’ the woman confides, flipping it on and then off again.

‘There’s this tiny spring inside the top.’ Gene points to the top of her torch, where the spring is situated. ‘I actually ended up replacing the one in mine.’

The woman studies the torch for a moment and then peers up at him, speculatively. ‘I suppose I should thank you for getting rid of the rat …’ She indicates, somewhat querulously, towards the bins. ‘I ran a bath a couple of hours ago, popped downstairs to fetch the watering can …’ She pauses (as if some kind of explanation might be in order, but then fails to provide one). ‘And when I came back …’

She shudders.

Gene struggles to expel a sudden vision in his mind of her reclining, soapily, in the tub. He clears his throat. ‘It was nothing,’ he mutters, then stares at the corner of her lip, fixedly, where her lipstick is smudged.

‘Well thanks for that, anyway,’ she says, her mouth tightening, self-consciously. He quickly adjusts his gaze and notices a light glow of perspiration on her forehead, then a subtle glint of moisture on her upper lip, a touch of shine on her chin, a further, gentle glimmer on her breastbone …

He quickly averts his gaze again.

‘I’m actually …’ She glances over her shoulder, frowning. ‘I’m actually in a bit of a fix’ – she leans forward and gently tips his clipboard towards her so that she can read the name on his identification badge – ‘Eugene,’ she clumsily finishes off.

Gene can’t help noticing her bare arms as she leans towards him. Her arms are very smooth. Utterly hairless. Slightly freckled. Her skin has a strange kind of … of texture to it and exudes – his nose twitches – a slight aroma of incense (Cedarwood? Sandalwood? Frankincense? Musk?).

Under her semi-transparent plastic apron, she’s wearing a strangely old-fashioned, tight, cap-sleeved khaki shirt (in the military style), unfastened to the breastbone with a jaunty, cotton turquoise bra (frilled in shocking red nylon) peeking out from between the buttons.

Gene blinks and looks lower. On her bottom half he can make out a pair of dark, wide-cut denims, rolled up to the knee. On her feet, some round-toed, turquoise shoes with neat ankle straps and high, straight heels.

‘… I mean I know it’s a little cheeky of me,’ she’s saying, ‘but it’s only eight doors down. The other side of the road – number nineteen …’

‘Pardon?’

Gene tries to re-focus.

‘My niece. I have to go and fetch her. It’s just …’ – she indicates over her shoulder – ‘I really should get back to my client. She wasn’t very happy about …’

She winces.

Gene stares at her for a moment, confused.

‘And if you’re headed in that direction anyway …’

He finally realizes what she’s getting at. ‘Oh. Wow. You mean you want me to go and …?’

‘Would you mind?’ She bites down on her lower lip.

‘Uh, no. No. Of course not. It’s fine,’ Gene insists. He glances up the road, appalled.

‘I’d go myself’ – she indicates over her shoulder again – ‘it’s just that I really should …’

‘Of course.’

Gene nods, emphatically. They stare at each other, wordlessly, in a strange kind of agony, like two distant acquaintances who’ve just met up, arbitrarily, in the waiting room of a VD clinic.

‘So what’s her name?’ Gene finally enquires.

‘Her name? Uh …’ She puts a tentative hand to her headscarf. ‘You know I honestly can’t remember …’ She frowns. ‘Isn’t that terrible? Something unpronounceable, like … like Hokakushi …’ Her frown deepens. ‘Or Hokusha. It’s Japanese.’

‘Your niece is Japanese?’ Gene deadpans.

‘My niece?’ The woman looks mystified, then mortified. ‘Oh God! Sorry …’ She shakes her head. ‘I’ve been up all night. I’m not firing on all cylinders, obviously. My niece … My niece. My niece is called Nessie. Nessa. And the woman who’s minding her is called Sasha …’ She pauses, sheepishly. ‘And I’m Valentine.’

She holds out a gloved hand. Gene reaches out his own, in automatic response, but before their fingers can touch, she quickly withdraws hers, apologizing, and starts trying to remove the plastic glove, muttering something about ‘needing to maintain hygiene’.

‘Don’t worry.’ Gene smiles, taking a small step back. ‘I should probably …’

‘Yes …’ Valentine’s eyes are now lingering on his wedding ring. ‘Well I suppose I’d better …’ She thumbs over her shoulder. ‘My poor client …’

‘Absolutely.’ Gene takes another step. He inspects his watch. She remains where she is, though, still gazing at him. He isn’t sure why, exactly.

‘You have the original glass,’ he mumbles, pointing, somewhat uneasily.

‘Pardon?’

‘The original glass panels, in the door …’ He can gradually feel his colour rising. ‘You’re one of the only houses left on the street.’

‘Oh. Yeah. Yeah. The glass …’ Valentine peers across at it, fondly. ‘My dad always loved it. He was completely obsessed by this period of design. I guess you could say it was his …’

Gene suddenly turns – while she’s still talking – and hurries down the short path, then out of the garden (the gate swings gently behind him). He knows it’s a little strange. He knows it’s a little rude. And even as he’s walking – just as soon as he starts walking – he’s reproaching himself for it (‘What is this? What are you playing at? Are you crazy?!’).

Valentine watches him go, surprised. He senses her blue eyes upon him, and feels – possibly for the first time in his adult life – an excruciating awareness of all his physical shortcomings. He automatically lifts his chin and pushes back his shoulders. He tightens his stomach. But even as he does so he’s haranguing himself for it, lambasting himself for it (‘You bloody fool. This is ridiculous. This is laughable’). His body feels leaden and yet light, all at once. His chest feels too small to contain his breath. He longs – above everything – to escape, to bolt, to flee. It’s as much as he can do not to break into a sprint.

‘They’re Gene’s,’ a sullen voice announces. ‘All of them.’

‘Huh?’

Ransom glances up, startled. He’s just been idly rifling through a deep drawer in a heavy, dark (and profoundly unfashionable) Victorian sideboard in a somewhat cramped and boxy sitting room. In one hand he holds a bowl of cereal (mini shredded-wheat, drenched in milk, which he’s eating with a fork), in the other he holds a medal. The person sullenly addressing him is a boy – a short, thick-set teenager with a dense mop of black hair (carefully arranged to hang, with a fastidious lopsidedness, over one eye) and a copy of Bruce Lee’s Artist of Life propped under his elbow.

‘I don’t know why he keeps them there,’ the boy continues, stolidly. ‘He’s got dozens of the stupid things. Mum’s always nagging at him to display them properly.’

‘I was looking for a spoon.’ Ransom quickly drops the medal back into the drawer, adjusts the towel he’s wearing (a pink towel) and turns to engage with the boy directly.

‘You finished the milk,’ the boy mutters, darting Ransom’s cereal bowl a petulant look before silently retreating.

Ransom glances down at his bowl, shrugs, devours another forkful, saunters over to a nearby bookshelf and casually scans the books on display there. After a brief inspection he soon deduces that the books are divided – by and large – into two main categories: the military and the spiritual. Ransom instinctively shrinks from the religious side and focuses his attention on the military end instead. Here, his eyes run over Clausewitz’s On War, Conrad Lorenz’s On Aggression, Richard Holmes’s Acts of War, then rest – for a brief interlude – on Wendy Holden’s Shell Shock. He carefully places down his bowl and pulls it out, opening it, randomly: ‘Too many people are jumping on the trauma bandwagon,’ he reads, ‘in a society where to be a victim confers on people a state of innocence.’

He scowls, tips the book over and inspects the cover, then slaps it shut and shoves it, carelessly, back into the shelves again. Next he removes the Clausewitz. ‘The element of chance, only, is wanting to make of war a game,’ he reads, ‘there is no human affair which stands so constantly and so generally in close connection with chance as war …’ He scratches his head, intrigued. ‘War is a game both objectively and subjectively …’ he continues, and then, ‘Every activity in war necessarily relates to the combat, either directly or indirectly. The soldier is levied, clothed, armed, exercised, he sleeps, eats, drinks and marches all merely to fight at the right time and place.’

Ransom ponders this for a moment and then places the book under his arm, grabs Richard Holmes’s Acts of War, and quickly flips through it, pausing for a moment, beguiled, at a section that discusses how man’s aggressive drive is inherited from his anthropoid ancestors. This genetic legacy apparently inclines him to fight members of his own species. Most other creatures, he discovers, avoid lethal combat with their own kind by employing a series of simple mechanisms like a pecking order, the ritualization of combat etc. Piranhas generally prefer to attack other piranhas with their tails rather than their teeth. Rattlesnakes air their grievances not by biting other rattlers but through bouts of wrestling …

‘Brilliant!’

Ransom chuckles to himself as he carefully turns over the corner of the page (for future reference), closes the book and shoves it under his elbow along with the Clausewitz.

His eye now settles on a tiny copy of Sun Tzu’s Art of War, which has been secreted, sideways, on top of a row. He pulls it out with a small, wry smile of recognition. It’s a miniature hardback – under three inches in width – wrapped, like an expensive chocolate, in shiny black, red and silver foil-effect paper. He enjoys the sumptuous feel of it in his hand. He opens it up.

‘Simulated chaos is given birth from control,’ he reads. ‘The illusion of fear is given birth from courage; feigned weakness is given birth from strength.’

He muses on this for a moment, his attention briefly distracted by the sound of a phone ringing in a far corner of the house. He can tell from the distinctive ringtone (Queen’s ‘We Are The Champions’) that it is his phone. He scowls. The ringing stops. His eye returns to the Sun Tzu and he slowly re-reads the previous sentence: ‘Simulated chaos is given birth from control; the illusion of fear is given birth from courage; feigned weakness is given birth from strength.’

Ransom considers this for a while, then he smiles, almost sentimentally, closes the book, carefully slots it under his elbow (alongside the other two) and is about to grab his cereal and move away when his eye alights on a distinctive-looking beige and black hardback with an old-fashioned drawing of an open palm on its spine. He pauses. His mind turns – very briefly – to the previous evening and to Jen.

Ah yes, Jen. Jen with her pale arms, her chapped upper lip and her infinite lashes. Jen with her ponytails and her pierced – and piercing – tongue. Jen. He winces. He draws in closer. Written above the illustrated hand he reads: Cheiro’s Palmistry for All; 2/6 NET.

‘Cheiro?’ He pronounces the name out loud, as if trying it on for size.

‘Cheiro.’

He pauses. Then, ‘Goll-uff,’ he murmurs, quizzically. ‘Gol-ol-ol-ol …’

He shakes his head. ‘Cheiro! Cheiro! Cheiro!’

He tweets the name like a canary, then snorts, pulls the book out and opens it up, randomly, to ‘an autographed impression of Lord Kitchener’s hand given to “Cheiro”’ –

‘Eh?’

– ‘on the 21st of July, 1894 (hitherto unpublished).’

As he gazes down at the photograph, two important things happen. The first is that the boy – the stroppy, dark-haired teenager – enters the room, holding out a dripping mobile.

‘I just found this in the toilet bowl,’ he’s saying. ‘Is it yours by any chance?’

The second is that a loose wad of papers falls down from within the pages of the palmistry book – an old letter, a dried flower, a couple of photos, the order of service for a funeral …

Ransom curses, loudly, as the order of service and the photo slide down on to the floor, but the dried flower and the letter plop into his cereal bowl. He instinctively snatches for the letter – keen to preserve it – but, in his panic, he clumsily knocks his knuckle into the fork and tips up the bowl, sending it (and all its contents) cascading down on to the carpet.

Ransom stares at the milky, wheaten mess, agog.

‘Wow!’ The boy is impressed (and Ransom can instantly deduce that it takes a fair amount to impress this kid): ‘You really fucked up,’ he announces, delighted (like all teenagers, immeasurably enlivened by the prospect of a catastrophe), ‘that stuff belonged to Mallory’s dead mum.’

Ransom’s already on his knees, yelping plaintively, plucking photos and dried flowers from the goo.

‘Kitchen roll,’ the boy announces, sagely, and then promptly abandons him.

‘I don’t understand,’ the woman mutters, peering over Gene’s shoulder. ‘You’ve come to collect Nessa, but now that you’re here you’ve decided to …’

‘Read the meter. Yeah.’ Gene tries to sound nonchalant as he straightens up, switches off his torch and scribbles the relevant digits on to his clipboard. ‘It’ll save me from bothering you twice, that’s all.’

‘I see.’

The woman gives this some thought, and then, ‘But you are actually friends with Valentine?’ she demands (she is short and heavy-hipped, with long, wavy, black hair, down to her waist, and a piercing, brown gaze). ‘I mean you do actually know each other?’

‘Uh …’ Gene frowns. He senses trouble. ‘Uh … Yes. Yes. Of course I know Valentine,’ he insists. ‘Of course I do.’

‘Of course you do.’ The woman laughs, nervously, then smiles up at him, somewhat ruefully. ‘God – I’m getting so cynical in my old age! I mean it’s hardly as if you just turned up at her house to read her meter and then the next thing you know she’s railroading you into …’

Gene clears his throat and glances off, sideways.

The woman pauses, alarmed. ‘I mean she wouldn’t …?’

‘Good gracious, no!’ Gene exclaims. ‘That would be …’ He struggles to find the right word, but can’t; ‘pathetic,’ he eventually manages.

Pathetic?

‘Yes.’ The woman’s keen, dark eyes search his face. ‘Sorry,’ she eventually apologizes (plainly mollified by whatever it is that she finds there), ‘you must think I’m completely paranoid.’ She shakes her head, exasperated, then turns and guides him down the corridor. ‘It’s just that I’ve known Vee since she was a teenager’ – she glances over her shoulder, raising a single, deeply expressive, black brow – ‘and she’s always had this incredible gift – this … this knack – for making people feel …’

She suddenly checks herself. ‘Have you been friends with Vee for long, then?’

‘Long?’ Gene parrots, like the word is somehow incomprehensible to him.

‘Yeah. Long. Long …’ She rolls her eyes, sardonically. ‘As in how’d the two of you first become acquainted?’

‘Uh …’ Gene tries to think on his feet. ‘I work in a bar. At the Thistle. In town.’

‘Okay …’

The woman nods, as if expecting something more.

‘It’s not full-time,’ he elects, ‘I just fill in when they’re short-staffed, sometimes.’

‘Right.’ The woman sniffs, nonplussed. She is silent for a moment and then, ‘Well it really has been incredibly tough on her,’ she confides (determined – in spite of Gene’s best efforts – to broaden the level of their interaction). ‘I mean what happened to her mother …’ She shudders. ‘And to lose her dad like that. Then all the problems with her brother. Then her sister-in-law being carted off into …’

She points her finger to her temple and rotates it.

‘Awful,’ Gene confirms, in studied tones.

‘Devastating,’ the woman persists. ‘And I do think she’s coped extremely well …’ she concedes (perhaps a little grudgingly), ‘I mean under the circumstances. Although in some respects she barely copes at all – just doesn’t have the emotional …’ She rotates her hands, struggling to find the correct adjective. ‘Chutzpah!’ she eventually finishes off.

They arrive at the kitchen door. She pushes it open and waves him through.

‘I blame the parents, obviously …’

She grimaces, self-deprecatingly, after delivering this cliché. ‘D’you have kids of your own?’

‘A couple.’ Gene nods. ‘A boy and a girl …’ He pauses. ‘Both adopted,’ he qualifies.

‘I mean I love Vee,’ she insists (barely acknowledging his answer). ‘Who doesn’t love Vee? She’s a wonderful girl. Very sweet. Very creative. Very genuine. Just a bit of a lame duck, really …’ She pauses, thoughtfully. ‘Reggie’s at the root of it all.’ She sighs. ‘Did you ever have the honour of meeting Vee’s dad?’

‘Vee’s dad?’ Gene frowns. ‘No. No. I don’t believe we ever …’

He passes through the door and then waits, politely, at the other side. Directly ahead of him is a large, kitchen table (currently covered in piles of washing), and beyond that, an open door which leads out into a long, lush and meandering back garden where a gang of children – mainly boys – can be seen playing together on a trampoline.

‘So you work two jobs?’

‘Pardon?’

Gene drags his eyes away from the carefree scene outside. The woman has grabbed a pair of matching socks from a prodigious, cotton-mix hillock and is now deftly rolling them into a single ball.

‘Two jobs?’ she repeats, inclining her head towards his clipboard.

‘Uh –’

‘Of course Reg adored Vee,’ she interrupts him, identifying a second pair and grabbing them. ‘She was the apple of his eye. Reg doted on the girl. Although he could be very strict with her – quite domineering – overbearing, even, on occasion. In fact I read this excellent article recently about how people with Vee’s …’ she pauses, delicately, ‘… problem …’ She pauses again. ‘I mean I suppose you should call it an illness, really …’ She looks to Gene for confirmation. Gene just gazes – pointedly – back out into the garden.

‘Well they normally have an overbearing father-figure,’ she persists, ‘a controlling dad. That’s apparently very common …’

While she’s speaking the woman is rolling up her shirtsleeve: ‘Here – take a look …’

She shows Gene a large, black and grey tattoo on her forearm which depicts a coffin lying on a bed of roses, inscribed with the words: MUM, RIP, 1946–1998.

Gene inspects the tattoo.

‘It’s a Reggie T original.’

She smiles up at him, proudly.

Gene re-examines the tattoo more closely. It’s certainly a fine piece of work: delicately inked, distinctive, very traditional.

‘D’you like it?’ she demands (possibly irritated by his protracted silence).

‘It’s great,’ he answers, a little awkwardly. ‘I mean it’s extremely’ – he frowns – ‘accomplished.’

She gazes down at the tattoo herself, somewhat mollified. ‘He was a filthy old bigot,’ she grumbles, unrolling her sleeve again. ‘A neighbour once told me how he developed his hatred of all foreigners after his mum had an affair with an American serviceman during the war. His dad went crazy when he found out. Did a hike. Reg was only a toddler at the time, but he never got over it.’

‘That’s tough,’ Gene volunteers, blandly.

‘Although – to Reggie’s credit – he’d never be rude to your face. Not directly. He was very charming in person. Very amiable. Always campaigned for the NF or the BNP at election time. Stood as the borough candidate every opportunity he got. Made no secret of his views, but was never nasty about it, never rude. I mean I’m half Filipino. My dad was from the Philippines. They’d play darts together down the –’

Her monologue is briefly interrupted by a sharp, girlish scream from the garden. She moves over towards the open doorway and blinks out into the bright sunlight.

‘Got any yourself?’ she wonders, after a short pause.

‘Sorry?’

‘Her last man was covered in them.’ She turns, patting her forearm, by way of explanation, ‘Hands, legs, feet. Had this massive, tangerine-coloured carp swimming across his neck – its eye just’ – she points to her throat – ‘just there. On his Adam’s apple. It’d bob up and down whenever he spoke.’ She grins. ‘Russian, he was. Size of a house. But wouldn’t say boo to a goose. Gentle as a mouse. Lovely boy. Ran off to live on an Indian commune with this woman they call “The Hugging Saint”. Very weird. Very weird. Did Vee ever tell you about all that?’

‘Uh, no. No she didn’t.’

Gene frowns, uneasily, his cheeks reddening. ‘And just for the record …’

As he speaks, another sharp, girlish scream resounds around the garden. The woman turns and peers outside again, shading her eyes with her hand this time.

‘Would you believe it?’ she mutters. ‘The little devil’s climbed straight back on again after I clearly told her …’

Gene glances outside himself. In the garden he sees a small girl bouncing up and down on a trampoline wearing a short, white, cotton dress and no underwear. As she bounces, a group of older boys stand nearby in a furtive huddle, watching on.

‘Awful, isn’t it?’ The woman turns and observes Gene’s slightly queasy look. Then, before he can answer, ‘In fact I’m glad you’re here to see it for yourself, because now you can have a word with Vee about it. I’ve tried to raise it with her before, but she always just fobs me off.’

Gene watches, transfixed, as the small girl bounces higher and higher, kicking out her legs with joyous abandon, each time providing the assembled company with an exemplary view of her dimpled buttocks and tiny vagina.

‘I mean they’re good boys – all of them,’ the woman insists. ‘It’s just that she’s way too young to be playing with this crowd, but she tags along with little Natalie, there …’

She points to another child, an older girl, who is sitting in a deck chair picking out pebbles from between the tread in her sandals.

‘Natalie’s at that age where she enjoys playing the “older sister” …’

‘Perhaps we should think about calling her in,’ Gene prompts.

‘Good idea.’

The woman pops her head through the open doorway.

‘Nessie? Nessa!’ she yells. ‘Get down off there and come inside, pronto!’

Pause.

‘NESSA!’

Pause.

‘NOW!’

The child finally stops bouncing.

‘She’s such a wilful little creature’ – the woman tuts – ‘a terrible exhibitionist. Was your own daughter ever that way inclined?’

‘Sorry?’

‘Did your own daughter …?’

‘Absolutely not!’

Gene’s almost aggrieved at the mere suggestion.

‘So you’ll speak to Vee about it, then?’

‘Uh …’

Before he can fashion a suitable answer, Gene’s phone starts to ring. He jumps, startled, reaches into his jacket pocket and pulls it out.

‘Hello?’

He turns to face the opposite wall (profoundly grateful for the temporary distraction).

‘Gene?’

‘Sorry …?’

It takes him a second to register the voice.

‘Jen?’

‘Yeah, you goof! Don’t sound so surprised. I bribed your number out of Nihal on reception.’

(Gene makes a quick mental note to have a quiet word with Nihal.)

‘I just wanted to check if you got home all right. Things got pretty crazy last night after you left.’

‘Oh. Yeah.’

Gene hunches his shoulders, defensively.

‘So did you manage to bundle him into the cab or what?’ she prompts him.

‘No. Uh …’

Gene switches the phone to his other ear. ‘I’m actually in the middle of something right now, Jen, could I possibly –’

‘There’s this terrible photo in the Daily Star website …’

‘Is there?’

‘And one in the Mirror’s. He’s sprawled over a car bonnet. It’s taken from the back, but it’s gruesome. In fact if you look really closely you can make out part of your arm – you’ve got him in some weird kind of head-lock …’

‘I was simply trying to hold him up.’ Gene scowls, exasperated.

‘He’d had a good skinful.’ Jen sniggers.

‘He had his cap pulled down over his face. Didn’t have a clue where he was going. Then someone knocked the thing askew in the scramble – probably a photographer – and he completely lost the plot. Started throwing punches, spitting, swearing – ended up vomiting all over the bonnet of the cab. The cabbie was livid and promptly drove off …’

‘Oh my God.’

‘… so I ended up just piling him into the Megane and driving him myself.’

As Gene speaks, the small girl enters the kitchen. He turns to look at her.

‘Where to? Back to the Leaside?’

The child peers up at him and smiles. She’s a beautiful little thing with angelic blue eyes and short, white-blonde curls.

‘Back to the Leaside?’ Jen repeats.

‘Uh …’ Gene frowns, struggling to focus. ‘No. No.’

He turns to face the wall again. ‘When we got back to the Leaside he became convinced that he wouldn’t be safe there, that we’d been followed. He got all tearful and melodramatic …’

He rolls his eyes. ‘It was quite a performance.’

‘So what did you do?’

‘What could I do? I just took him home and stuck him in Mallory’s bed for the night.’

‘Bloody hell!’ Jen chortles. ‘Back to the rectory?!’

‘It was fine. Mallory came in with Sheila and me. He’d virtually passed out by that point, anyhow –’

‘So where’s he now?’ Jen interrupts.

‘I haven’t a clue.’

‘Won’t he still be at your place?’

‘I doubt it.’ Gene frowns, peering down at his watch.

‘Well give me your home phone number and I’ll check,’ Jen suggests.

‘Sorry?’

Gene’s patently not sold on the idea.

‘Your home phone number. So I can check.’

‘But I’m pretty sure –’

‘Just give it to me, Gene!’ Jen snaps.

Gene gives her the phone number.

‘Brilliant! You’re a star!’

Jen hangs up.

Gene removes his phone from his ear and stares down at it for a second, scowling, then shoves it back into his pocket, draws a deep breath, carefully fixes his expression and turns.

‘So let’s get this show on the road, shall we?’ he exclaims, holding out his hand to the child with what he hopes is an air of confident jocularity.

‘Is it salvageable?’

They are hunched over the cracked and fissured lemon-coloured laminate of the breakfast bar in the rectory’s rickety, L-shaped kitchen, inspecting the sodden letter.

‘I don’t know.’ Stan scowls. ‘I mean I’ve done my best with the first page …’

He holds it up to the light, squinting. ‘But it’s very blurred in places …’

A bare-chested Ransom snatches it from him, impatiently.

‘It’s perfectly legible!’ he exclaims.

‘Yeah, well …’

Stan isn’t convinced.

‘You’ve done a brilliant job!’ Ransom enthuses, picking up the pressed flower. ‘And the flower’s still basically intact, which is great …’

‘It’s a flowering clover,’ Stan mutters. ‘A lucky clover. It had four leaves originally.’

‘So?’

Ransom refuses to be dispirited.

‘So one of the leaves is now completely …’

Stan grimaces as he points to it. ‘That’s just mangled.’

Even Ransom can’t deny the harsh truth of this statement. ‘Yeah. Yeah. But …’ He blows softly on the clover (hoping to bulk it out with his breath, perhaps). ‘But you still get the general idea …’

Stan picks up the damaged photo. It’s an old, black and white publicity shot of a young, dark-haired, female contortionist in a harlequin-style leotard (with the obligatory white, frilled ruff) performing an exaggerated backbend. Her face smiles out from between her ankles (her chin resting, jauntily, on her hands). A quantity of the shredded wheat obscures one leg, knee and foot.

‘Her face is fine,’ Ransom mutters, peering, intrigued, at her sharply jutting pubic bone. ‘If we could maybe just …’ He leans over and starts prodding, clumsily, at a damp strand of the wheat with his forefinger.

‘Careful!’ Stan yelps, snatching it away. ‘The photographic ink’s still really unstable.’

Ransom withdraws his hand, jarred.

‘Perhaps we should use a hairdryer?’ he volunteers. ‘See if it peels off more easily once the liquid’s all evaporated?’

‘Yeah.’

The kid doesn’t seem especially enthused by this notion. He places down the photo (beyond the golfer’s reach) and picks up the Order of Service.

‘How’s that thing coming on?’ Ransom reaches over and grabs a hold of it. The paper on the bottom half has bubbled up and the print has become furry in several places. He gives it a tentative sniff.

‘Not too bad,’ he murmurs (wincing at the sour smell of the milk), ‘I mean we’re definitely making progress here …’

As Ransom appraises all the artefacts, en masse, he suddenly feels curiously distended again. Swollen. Like a sheep bloated with methane. He puffs out his cheeks (as a physical expression of this odd, internal sensation) and then expels the air, violently (producing a loud, hollow, farting sound).

Stan glances up, startled. The golfer tosses down the Order of Service and picks up Stan’s copy of Bruce Lee’s Artist of Life. ‘This thing any good?’ he asks, idly flipping through it.

‘Depends on your definition of “good”,’ Stan answers, somewhat inscrutably.

Ransom thinks for a few seconds. ‘Gisele Bundchen’s baps,’ he eventually volunteers.

Stan carefully considers this suggestion. ‘I’m not sure if that’s an appropriate frame of reference,’ he eventually concludes.

Ransom places down the book again. ‘I actually had a brief correspondence with Linda Lee Cadwell …’

‘Lee’s wife?’

Stan’s impressed. ‘What about?’

‘I dunno. Bruce. Fame. Mysticism. Sport. Competition. Life …’

Ransom commences picking, distractedly, at an ingrown hair on his forearm.

‘So once we’ve dried all this stuff off,’ he eventually mutters, abandoning the ingrown hair, gazing down at his naked torso, tensing his chest muscles and watching his generous, brown nipples jerk skyward, ‘then what?’

Stan frowns, focusing on the nipples himself (his dark brows automatically arching, in sync). ‘How d’you mean?’

‘Well d’you reckon it might be possible to just stick it all back into the book and … uh …’ Ransom shrugs.

‘What?’ Stan looks scandalized. ‘Bang it back on to the shelf again like nothing’s happened?’

Ransom shifts in his seat, quickly diverting his attention from Stan’s accusing gaze to a small window cut into the tiling above the stainless-steel sink. Beyond this window stands a large vehicle covered in tarpaulin.

‘What is that out there?’ he demands, rising slightly. ‘A truck of some kind? A jeep?’

‘But wouldn’t that just be wrong?’ Stan interrupts, refusing to be diverted.

Ransom flinches at the word ‘wrong’. He abhors moral imperatives. The word ‘wrong’ hangs in the air between them, buzzing, self-righteously, like an angry black hornet.

‘Absolutely,’ Ransom finally concedes, smiling brightly as he sits back down again, ‘of course it would be wrong. Of course it would be. I was just thinking out loud – just trying the idea on for size – brainstorming, if you like … Although …’ He pauses, thoughtfully. ‘Although in my experience, which is – as I’m sure you can imagine – pretty extensive …’ (He pauses again, portentously.) ‘Golf is principally a game of the mind, a game of strategy, after all … I’ve generally found that actually telling people about something like this – a serious problem or a terrible catastrophe – confronting them with it, unhelpfully, at an inappropriate moment, can often end up generating more hurt and distress than simply letting the whole thing unfold in a more gradual, a more natural, a more … uh … how to put this? A more organic way.’

‘But if we just stick the book back on to the shelf again and say nothing,’ Stan interrupts, scowling, ‘what happens when they do eventually find out? Won’t I just cop all the flack for something that wasn’t even my fault?’

‘You?’ Ransom appears stunned by this humble teenager’s fundamental grasp of basic, deductive logic. ‘But why on earth would they blame you? That’s totally illogical! Like you say, it wasn’t your fault …’ He pauses, thoughtfully. ‘Although if you hadn’t come charging into the room, at the worst possible moment, like a bull in a bloody china shop …’

As Ransom speaks he darts a malevolent look towards his phone (where it currently sits, moistly – but still disturbingly functional – on the countertop).

‘Well who else are they going to blame?’ Stan snorts.

‘They might not blame anyone!’ Ransom declaims, indignant. ‘They might not even notice anything’s wrong. They might just put the staining down to a little natural wear and tear, or think that there’s a touch of damp behind the bookshelf, or …’ He pauses. ‘Or an infestation of silverfish. It’s a common enough problem, uh …’

He peers at Stan, enquiringly. ‘What was your name again?’

‘Stanislav,’ Stan enlightens him.

‘Polish?’

Stan nods. ‘On my dad’s side.’

‘Really? Gene’s a Pole?’ Ransom’s surprised.

‘Not Gene. I mean my real dad. Gene’s my stepdad.’

‘Oh. Okay.’ Ransom accepts this information, impassively. ‘Well, for all we know, Stanislav,’ (he promptly returns to the issue at hand), ‘it’s entirely possible that nobody will get around to picking up this book and looking inside it for weeks – months – years, even. In fact it’s not beyond reason that we might actually be the last two people on the planet ever to handle this thing.’

He holds up the palmistry book with a suitably portentous expression.

‘I seriously doubt that,’ Stan quickly (and firmly) debunks his theory. ‘It’s a precious, family heirloom, not just some crummy, old book that nobody cares about.’

‘But that’s the very nature of an heirloom, don’t you see?’ Ransom exclaims, frustrated. ‘They’re not especially important – not in themselves. They’re just old things from the past that “represent” stuff …’ – he rolls his eyes, boredly – ‘stuff about, urgh … I dunno … ideas and memories and feelings and shit, but they don’t actually mean anything. They’re not actually worth anything …’

‘Well you were interested enough to take a look at it,’ Stan mutters.

‘This house could suddenly go up in flames!’ Ransom leaps to his feet, dramatically. ‘Tonight! Next weekend! An electrical fault! It could be razed to the ground! Then all this worrying and heart-searching will’ve been a complete waste of bloody energy.’

Stan indicates, mutely, to a small, flashing smoke alarm which is situated on the ceiling directly above their heads.

‘A flood, then,’ Ransom improvises, irritated. ‘A flash-flood – and you barely have time to evacuate the place …’

‘In Luton?!’ Stan snorts.

‘Yeah. Why not?’

‘No big rivers.’

‘None at all?’

‘The Lee, but that hardly counts.’

‘No canals? No lakes?’

Stan gives this some thought. ‘I suppose there’s always the lake over in Wardown Park, but that’s –’

‘A burst water main! Hah! ’ Ransom slaps the worktop, victorious. ‘I rest my case!’

‘These are Mallory’s things, anyway,’ Stan persists (instinctively shielding the vulnerable clover from Ransom’s violent show of exuberance). ‘They’re her dead mum’s things. They belonged to her dead mother,’ he reiterates (just in case Ransom was in any, remaining doubt about the objects’ sacred provenance). ‘Mallory’s the one you’ve got to be seriously worried about here.’

‘Mallory’s just a kid!’ Ransom swiftly pooh-poohs him. ‘She probably won’t even notice …’

‘Oh really?!’ Stan guffaws. ‘You obviously don’t know Mallory very well. Mallory’s officially the world’s most uptight kid. She’s a neat-freak – a lunatic. She pretty much has a heart attack if she steps in a puddle on her way to school. Top of her Christmas list last year was a shoe store and a lint roller.’

‘Well I bet Mallory has loads of knick-knacks knocking about the place from when her mum was still alive,’ Ransom contends.

‘There was her mum’s old teddy bear …’ Stan willingly concedes.

‘A teddy bear!’ Ransom throws up his hands. ‘Perfect! What better memento of a loved one than a teddy bear?’

‘… but it was destroyed by moths,’ Stan finishes off.

‘Oh.’

‘And there was her mum’s gold, heart-shaped locket with a tuft of her dad’s hair hidden inside …’

‘Bingo!’ Ransom snaps his fingers. ‘Top that! Precious, wearable and sentimental.’

‘… but it was stolen from her locker at the swimming pool last year.’

A lengthy silence follows in which Ransom stares, inscrutably, into the middle distance (pulling rhythmically – and not a little repulsively – at the hair under his armpit), until, ‘So what the heck is that thing?’ he finally demands, pointing. ‘A jeep, a van, a truck …?’

‘Cheiro,’ Gene says, ‘was this well-known –’

‘Palm-reader,’ she interrupts, ‘and a clairvoyant. Yeah. I know all about him.’

Valentine holds out her hand. ‘Can I take a proper look?’

Gene removes the ring from his little finger and passes it over. They are standing in the hallway together.

‘Although the story’s probably just apocryphal.’ He shrugs, noticing how her make-up is perfect now (the bright, red lipstick no longer smudged at one corner but adhering – neatly and faithfully – to the smooth line of her lips).

‘Apocry-what?’ She grins up at him.

‘Apocryphal. Not genuine. My mother was a professional palmist. I suppose it was a rather convenient piece of lineage to have.’

Valentine inspects the ring closely.

‘It’s incredibly pretty,’ she murmurs. ‘Is that a ruby?’

As she pores over the ring, Gene’s eyes are drawn to the short, delicate fronds of auburn hair at the nape of her neck which protrude – in irresistible wisps – from below her scarf.

‘Is that a ruby?’ she repeats, glancing up.

‘A ruby?’ Gene starts. ‘No. No, it’s actually a garnet. I believe it’s Persian. He apparently wore it on the little finger of his right hand to ward off evil spirits.’

He smiles, drolly.

‘And the cigarette case? Do you have that, too?’ Valentine wonders (ignoring the drollery).

‘Pardon?’

‘The cigarette case. Wasn’t it the silver cigarette case that saved his life when he was stabbed by a disgruntled client in his New York apartment?’

Gene looks bewildered.

‘There’s no official biography’ – Valentine shrugs – ‘but you can find out all about him on the internet. His books still sell in bucket-loads – they’re considered classics in the field. From what I can recollect, I’m pretty sure he was raised in Ireland, although he finished up in California, working as a screenwriter …’

‘I get the general impression,’ Gene interjects (somewhat dryly), ‘that his personal history probably always owed a certain debt to the screenwriter’s art.’

‘So there’s a powerful emotional connection with your mother, at the very least,’ Valentine ruminates.

Gene frowns, not following her logic.

‘They both enjoyed spinning the odd yarn.’ She grins.

He considers this for a second and then smiles himself.

‘Although if your mother’s story is to be considered credible,’ she reasons, ‘if the connection is biological, then you’d actually be his great-great-nephew or something …’ She raises a mildly satirical brow. ‘I never got the impression that Cheiro was “the marrying kind”.’

‘There was a sister,’ Gene muses, ‘a Mary Louise Warner, but I suspect our connection might’ve been by marriage alone.’

Valentine continues to inspect the ring.

‘Anyhow …’ Gene draws a deep breath, struggling to re-focus. ‘I just didn’t feel it would be right to let the incident pass without at least drawing your attention to it in some way.’ He glances down the corridor and indicates (somewhat limply) towards the child.

Valentine slips the ring on to her index finger, straightens out her arm and holds it at a distance (to admire it, in situ). ‘I’m really interested in palms,’ she murmurs, turning her hand over and inspecting her own, ‘I’m obsessed by the skin, in general, same as my dad was. Just how strong it is – how tough and soft and durable. The skin’s actually the largest organ of the body. Did you know that?’

Gene doesn’t respond. He’s still peering over at Nessa who is currently having a loud, imaginary conversation on the heavy, black, Bakelite phone.

‘Just forget about the other thing.’ Valentine smiles (glancing over towards the child herself). ‘Sasha’s so uptight about that kind of stuff. Nessa’s still a baby. She’s a free spirit. She hates to feel confined – hemmed in – by clothes, walls, rules … And she’s the world’s worst exhibitionist. I’ve got no idea where …’

Valentine pauses for a second, mid-sentence, then frowns. ‘I mean I’m sure she’ll grow out of it. It’s just this silly phase she’s going through.’

‘She’s certainly quite a character,’ Gene murmurs as Nessa lifts up the back of her dress, pulls the hem over her forehead and commences wearing it as a kind of half-veil, beaming all the while.

‘She’s completely brazen!’ Valentine chuckles. ‘Brimming with confidence! Life has a nasty habit of knocking the stuffing out of people …’ She gazes up at him, appealingly.

‘I take your point,’ Gene concedes, ‘although I do think that when girls reach a certain age …’ He pauses, cautiously. ‘And I have a daughter of my own, so I’m speaking from painful experience here … These things can occasionally start to develop – if you’re not extremely careful – into something rather more … uh … something rather more …’

‘But she’s still just a baby!’ Valentine repeats.

‘Yes. She is. Absolutely …’ Gene clears his throat. ‘It’s simply that the other children in the group – the boys, in particular …’

Gene focuses, intently, on the aspidistra. He can’t quite believe he’s having this conversation.

‘The boys?’ Valentine’s brows rise.

‘Yeah. Yeah. The older boys,’ Gene murmurs. ‘It’s nothing explicit, nothing … just a … a particular kind of … well … a certain kind of … of atmosphere …’

‘An atmosphere?’ Valentine looks shocked. ‘An atmosphere?’ she repeats, lifting a tentative hand to the back of her head.

‘Yeah …’ Gene follows the progress of the hand from the corner of his eye (it’s an attractive hand – soft and graceful, with lean, tapering fingers. An artistic hand, he suddenly thinks, switching, automatically, into palm-reading mode, a conic hand …). ‘Yeah …’ he repeats, blinking. ‘I mean they’re certainly not doing anything … anything inappropriate, they’re just naturally … uh … inquisitive. Just registering an … an idle interest, so to speak. There’s nothing … nothing specifically wrong about it – not exactly … yet it still feels slightly … well …’ – he winces – ‘slightly … what’s the word? I don’t know … slightly, uh, well, unsavoury …’

‘Unsavoury?’ Valentine snorts, incredulous. ‘Bloody hell! They’re only kids, for heaven’s sake!’

‘Absolutely!’ Gene insists. ‘Completely!’ he reaffirms. ‘I mean it would be ridiculous – stupid, ludicrous – to blow this thing all out of –’

‘Wouldn’t it, though?’ Valentine interrupts, tartly.

Gene winces, stung.

‘I’m sorry,’ she immediately apologizes.

‘No.’ Gene shakes his head. ‘It’s fine. I probably deserved that. I’ve overstepped the mark.’

A strange pulse passes between them.

‘It just seems like a sad reflection of the modern world,’ Valentine finally volunteers, ‘if an innocent, little girl, a child, can’t just –’

‘If you’ll forgive me for saying so,’ Gene promptly interrupts her (his confidence burgeoning, exponentially, as the discussion moves from the personal to the generic), ‘this isn’t really about the relative goodness or badness of the world. It’s not a complex social or philosophical issue, it’s purely a pragmatic one – a practical one. It’s essentially about accepting our responsibility as adults. Children need protecting – as much from themselves as from other people – protecting from their own innocence, even …’

As Gene speaks, a commotion becomes audible in the street outside. A vehicle pulls up at the kerb, the engine cuts out, car doors slam, the gate creaks, footsteps can be heard tramping up the garden path (and voices, engaged in lively conversation).

Valentine gives no indication of having noticed, though. She continues to stare up at him, totally engrossed in what he’s saying, her lips moving as his lips move, her hands knitted together so tightly that the knuckles are whitening. On noticing her hands – the stress in them – Gene suddenly loses the strand of what he’s saying. He glances over towards the door. ‘I should probably … uh …’ he mutters, gesticulating.

Valentine says nothing for a few seconds and then, ‘Yes,’ she murmurs, her voice unexpectedly flat and colourless. Gene turns and takes a small step forward.

‘Wait …!’

Valentine reaches out her arm and touches his shoulder. He spins around, as if stung. She pulls his ring off her finger and offers it to him. He takes it from her. He starts to say something – something off the cuff, something low and intense and curiously heartfelt – then the door flies open and his words are swiftly obliterated in the ensuing commotion.

‘Shouldn’t you be at school or something?’

They are standing in the garden together inspecting a large, tarpaulin-covered vehicle. Ransom has thrown on his jeans again (in haste – one of the pockets is hanging out) along with an antique, military cap and matching jacket (he’s still resolutely bare-chested underneath it). The uniform he unearthed (mere moments earlier) in the hallway cupboard as Stan hastily disposed of the mop and bucket.

The cap’s a perfect fit, but the jacket’s strong, sepia-coloured fabric forms two taut ridges between his shoulder blades and creaks a fusty protest from beneath his armpits.

‘I’ve got the day off, actually,’ Stanislav swanks.

‘Really?’ Ransom starts grappling, ham-fistedly, with the tarpaulin. ‘How’d you manage to wrangle that, then?’

‘School Exchange Programme.’ The teenager tries (and fails) to look nonchalant. ‘I’m flying to Krakow this afternoon. For a month.’

‘Ah, Krakow.’ Ransom smiles, dreamily. ‘There’s a fabulous Ronald Fream course in Krakow. The Krakow Valley Golf and Country Club. Ever played there?’

Stan shakes his head.

‘Well you should definitely check it out if you get the opportunity. It’s fuckin’ amazing. There’s this crazy – almost … I dunno … Jurassic – feel to the landscape. The tee distance is incredible – something like six and a half thousand –’

‘I’m actually more into basketball myself,’ Stan interrupts, pushing aside a couple of the tarpaulin’s supporting bricks with a pristine-trainered toe.

‘Basketball?’ Ransom is nonplussed. ‘D’you play at all?’

As he speaks he instinctively starts feeling around inside the pocket of the jacket for his cigarettes, but ends up gingerly withdrawing an old, red tassel – heavily faded – of the kind that might be attached to a trumpet or bugle. He stares at it for a moment, perplexed, then shoves it away again, frowning.

‘I started the school team,’ Stan volunteers.

‘Really?’ Ransom appraises him, quizzically. ‘But surely you’re way too short to take it seriously? I mean how tall are you?’ He quickly sizes him up: ‘Five foot four? Five foot five?’

‘Basketball’s huge in Europe right now,’ Stan mutters (as if his chosen sport’s burgeoning size on the international scene must, inevitably, have some significant bearing on his own – admittedly diminutive – status), ‘and it’s really massive in the old Eastern Bloc: the Russians just can’t get enough of it.’

‘They friggin’ love it in China,’ Ransom volunteers, ‘and let’s face it’ – he shrugs, obligingly – ‘they’re pretty much all short-arses over there.’

Stan gazes at the golfer, balefully, as if awaiting a punchline (or – better still – a sheepish retraction of some kind). None is forthcoming.

‘I used to love shooting hoops as a kid,’ Ransom reminisces, ‘but golf was always destined to be my game of choice. I suppose you could say it was written in the stars …’ He waves a lordly hand, heavenward. ‘I mean I was sporting mad, in general; played footie, rugby, had a stunt-bike, skated, skateboarded. We lived alongside this small, public course in Ilkley. I started caddying for my dad just about as soon as I could toddle. Then, after inheriting my grandad’s old clubs when I was around four or five, I started taking a serious interest in the game myself …’

‘Four or five?’ Stan echoes, almost disbelieving.

‘You betcha!’ Ransom nods. ‘Dad wanted to cut the clubs short but I wouldn’t hear of it. Had quite a tantrum about it as I recall. Because I always enjoyed playing with them at full stretch.’ He lifts his chin, proudly. ‘I relished the challenge. I suppose you could say I’m from the “Grip it and rip it” school. A feel player. My swing’s always been pretty powerful, pretty distinctive, pretty … uh … loose.’

Ransom performs a basic simulacrum of his swing (although its grand scope is somewhat retarded by his beleaguered armpits). ‘Pundits like to call it “unorthodox”, or … or “maverick”’ – he grimaces, sourly – ‘or “singular”. Peter Alliss – the commentator? On the BBC? – he once called it “grotesque”. Grotesque?!’

The golfer gazes at Stan, horrified. ‘Unbelievable!’

Stan opens his mouth to comment.

‘But what Alliss simply doesn’t get,’ Ransom canters on, oblivious, ‘what he never got, is that I’m an instinctive player, a gut player. I play straight from here …’ He pats his breast-pocket, feelingly. ‘The heart,’ he adds (no hint of irony), ‘and that’s something you’re born with. It can’t be taught. I learned my game from the floor up. I developed it as a kid, inch by inch, through trial and error. Adapting my stroke – experimenting – making judgements – taking risks. I was relentless. Never took a lesson. Never needed to. Just used these …’

Ransom points at his two eyes: ‘Drank everything in, like a sponge. And it bore fruit. By ten I was playing off a handicap of seven …’

(Stan’s grudgingly impressed.)

‘By thirteen I was playing off scratch. Although my game went to shit for a while after my parents split up …’ Ransom begins searching the pockets of the military jacket for his cigarettes (then realizes – with a start – that the jacket isn’t actually his). ‘Got a fag on you by any chance?’

Stan shakes his head.

‘Messy, messy divorce.’ The golfer sighs. ‘My handicap shot up to five after Mam moved to St Ives with Roderick, her new partner. Although – on a purely selfish tip – I’d’ve never got to spend my summers down on the coast if the old folks’d stayed together. As it was I just had a blast, basically; staying out all hours, running wild, ripping it up in the surf … And whenever I got myself into a tight spot’ – he grins, mischievously – ‘exploiting that trusty, parental guilt mechanism for all it was worth …’

‘Jammy bastard,’ Stan mutters, jealous.

‘Don’t get me wrong,’ Ransom rapidly backtracks (keen to maintain his hard-bitten, northern lustre), ‘first and foremost I was always a hustler. Had to be. My folks weren’t made of money. Dad sold car insurance for a living. Mam worked in the school canteen. I raised the funds to surf by playing golf for cash. And while I was never what you might call an ambitious player, at least not in the formal sense of the word – never gave a toss about trophies and prizes and all that crap – I was competitive as all hell. Still am, to a fault. It’s like …’ He frowns. ‘It’s like I don’t care if I win the tournament, but I do care if I get thrashed by some smarmy, tight-arsed, Norwegian dick, dressed head to toe in fuckin’ …’

Ransom throws out an irritated hand. ‘… fuckin’ Galvin Green, who spends his entire life nibbling on energy bars and doing bench presses in the fuckin’ gym. It’s personal with me. Always has been. A pride thing. I need to be the big dog – the biggest dog – win or lose. And if I’m gonna lose, then I’ll piss all over the fairways. I’ll leave divots a foot fuckin’ deep. I’ll give the groundsman a fuckin’ coronary. I’ll be filthy. I’ll lose like a fucking pig. I’ll lose worse than anyone ever lost before. I’ll make an art out of it. I’ll hit the ball through the clubhouse window. I’ll play five shots from the car park. Because I’m a wild-card, Stan, a headcase: “Better to burn out than to fade away.” That’s always been my motto.’

Stan gazes at him, blankly.

‘Neil Young, dipstick! It’s the lyric Kurt Cobain quoted in his suicide note. You’re a teenager – you should know that. I quoted it at my coach the other day and he just stared at me, like – duh? I go, “It’s Neil fuckin’ Young, Roger.” He goes, “Neil Young? Of course it’s Neil Young! I love Neil Young! Are you kidding me?! The Jazz Singer’s my favourite film of all time!” I just looked down at myself and I thought, Ransom, you’re on a hiding to friggin’ nowhere here. So I sacked the little turd, on the spot.’

‘Seriously?’ Stan’s impressed.

‘Yeah.’ Ransom bridles. ‘Of course I’m fuckin’ serious. Although now the greedy twat’s suing me for unfair dismissal.’

‘Ouch.’

Stan looks pained.

‘The more I think about it, though,’ Ransom muses, adjusting his cap to a less rakish angle, ‘the more I feel like I’m … I dunno … like I’m a man out of time …’ He pauses, wistfully. ‘Nah-ah,’ he promptly corrects himself, ‘it’s worse than that. Sometimes when I walk into the locker room at the start of a tournament I feel like I’ve just landed from another planet. Like I’m extraterrestrial. An alien! And it’s not just that I’m Old School, that I’m Hardcore … It’s much more … I dunno … much more fundamental. There’s something different about me. A uniqueness. I have this … this natural … this basic … this essential quality about me which marks me out from ninety-nine per cent of players in the professional game right now …’ Ransom fixes Stanislav with an implacable stare. ‘D’you know what that quality is, Stan?’

Stan shakes his head.

‘Shall I enlighten you?’

Stan shrugs.

‘Personality!’ Ransom grins. ‘It’s personality, kiddo! I have character. Gallons of the stuff. And I’m just too damn creative – too much of a fuckin’ individual – to turn myself into one of those gormless, brainwashed, Ledbetter-style automatons who only ever plays the next hole, the next shot, while spouting endless, turgid platitudes about their “mental game” and the arc of their fucking “swing plane”. D’you know what I mean?’

Stan just gazes at him, blankly (he has no idea).

‘Lemme put it this way.’ Ransom gamely attempts to re-state his position: ‘I remember this shit-for-brains journo cornering John Daly outside the clubhouse at the start of a major tournament one time – I forget which tournament it was, off-hand – getting right up in his face and demanding to know what his “golfing strategy” was for the week’s play ahead. Daly’s obviously really unimpressed by this half-wit’s attitude, not to say bored and pissed off by the question itself, but, as always, he’s very friendly and courteous and listens to the journalist really politely before considering his reply. “My strategy?” he finally murmurs, plucking at his chin for a moment as if he’s going to say something really deep, really significant. “Yeah … Well I guess that would probably be …”’ Ransom clears his throat and then attempts a (perfectly passable) impersonation of Daly’s slow American drawl: “Hit the ball, find the ball, then hit the ball again.”’

Ransom smiles at Stan, beatifically. Stan looks puzzled.

‘“Hit the ball, find the ball …”’ Ransom repeats, slapping his hand against his thigh, snorting, ‘like this is the most incredibly profound, fuckin’ insight: “Hit the ball, find the ball …” Like this is the hugest fuckin’ revelation! Man! It was pure, undiluted genius! A defining moment in the history of the game! A two-finger salute to all the vultures and the bullshitters and the mind-wizards and the … the …’ (Ransom momentarily runs out of suitable targets for his mirthful ire, and flounders. His eyes fill with sudden, hot tears.) ‘It was absolutely fuckin’ brilliant,’ he huffs, then turns – blinking, self-consciously – and gazes, impatiently, past the modern, slightly shabby rectory building, to the large, somewhat static and forbidding, Victorian, red-brick church beyond.

‘What was that phrase Dad always liked to use?’ Valentine wonders, indicating, somewhat wryly, towards her mother. ‘Full of piss and vinegar?’

Her mother – who seems in unusually high spirits – is singing ‘Frère Jacques’ at the top of her lungs to a slightly bedraggled cat which is crouching, terrified, halfway up the stairs.

‘So what’re they trying to pin on me this time?’ Noel demands, slowly unwinding a grubby-looking keffiyeh scarf, while carefully ensuring that the sterile gauze dressings (which have been neatly applied to his neck beneath it) remain intact.

‘Pin on you?’ Valentine’s down on her knees, unfastening Nessa’s shoes. ‘Who d’you mean?’

‘Who?!’ Noel exclaims, thumbing over his shoulder, towards the front door. ‘Who the fuck else, stupid?!’

‘Watch your mouth, stupid!’

Valentine glances up at him, indignant, as she removes the first shoe. ‘And don’t call me stupid,’ she adds (as a guilty afterthought), inclining her head, warningly, towards the child.

‘Yeah, stupid !’ Nessa immediately echoes, snatching her other foot from her aunt’s grip, jutting out her chin and boldly squaring up to him.

‘Oh great.’ Valentine rolls her eyes.

‘Yeah, stupid !’ Nessa repeats, grabbing a handful of the baggy fabric of her father’s jeans and yanking at it, hard.

‘Get the fuck off!’ Noel screeches, snatching for the belt on his trousers (which are already alarmingly low-slung), but his response is too slow, and the trousers slip down, with virtually no resistance, from his hip-bones to his knees.

Nessa clings on to the concertinaed fabric, giggling, delighted. Valentine struggles to contain a wan smile.

‘Enough!’ Noel hisses, raising the back of a warning hand to the child. Nessa promptly lets go and Noel yanks the trousers up again, cursing. Valentine pulls the toddler back towards her and embraces her, protectively.

‘MUM!’ Noel bellows – effortlessly displacing his irritation (principally, admittedly, with himself). ‘Could you put a bloody sock in it, please?’

His mother sings – if possible – still louder.

‘I said could you put a sock in it?’ Noel repeats (an added edge of menace in his voice this time).

‘She’ll carry on for hours at this rate,’ Valentine mutters (with a strong element of ‘and I can’t say I’d blame her if she did …’).

‘She’s been singing that damn thing, non-stop, since we left the day centre,’ Noel gripes. ‘It’s driving me round the twist.’

‘Let it go, Bro’,’ Valentine advises him, stifling a yawn.

‘I had to remove her filthy hand from my thigh, twice, in the car on the drive home,’ Noel hisses. ‘She’s absolutely, bloody disgusting!’

‘I’ll have a word with her about it, later,’ Valentine promises, untangling one of Nessa’s bright, blonde curls with a distracted finger.

‘So where’s your client?’ Noel demands, suddenly glancing around him.

‘Gone.’ Valentine shrugs. ‘I called her a cab.’

‘Jeez. That was one hell of a turnaround,’ Noel murmurs (cheerfully ignoring the fact that he’d promised, faithfully, to transport her himself). ‘Was she happy with the end result?’

‘I dunno … Yeah’ – Valentine nods – ‘so far as I could tell. She was shy. Her English wasn’t great, but she cried when she saw it in the mirror.’

Pause.

‘Did she pay in cash?’

Her brother tries to appear disinterested.

‘By cheque …’

Valentine starts to remove Nessa’s other shoe.

‘I thought we had a strict rule about that,’ Noel grumbles.

‘We do …’

Longer pause.

‘… but she needed some of the cash she’d put aside to pay for her ride to the airport.’

Noel turns to glower at his mother again (who is now banging along in time to her ditty on the wooden banister).

‘So how’d it look?’ he demands, turning back to face her.

‘Fine. Nice. Good. Although I was so knackered by the end of it that I could hardly …’

‘But she was happy?’ he repeats.

‘Yeah. So far as I could tell. The skin was incredibly delicate – unusually delicate. I really had to hammer away at it.’

‘Did you get a photo?’ Noel demands.

‘For my portfolio?’ Valentine asks, fixing him with a dry look.

‘Why else?’ He shrugs, grinning.

‘Why else,’ she echoes, smiling back.

‘So did you?’ he persists.

‘Nope.’ Valentine shakes her head. ‘It was difficult to get her to trust me and relax. I mean after all the fuss at the hotel …’

Noel raises a tentative hand to his throat.

‘And – like I said – her English wasn’t all that great. She was really stressing out about making her flight in time. She’d lied to her husband about taking the trip. She’d told him she was visiting her sister in Osaka. She didn’t want him getting suspicious. She was planning to surprise him for their anniversary …’ Valentine pauses for a second, cradling Nessa’s tiny shoe in her hand. ‘Then, just when I was about to take the plunge and ask her, this guy turned up to read the meter and walked in on us by mistake –’

‘Hang on a second,’ Noel interrupts, alarmed. ‘Which guy? Not the hotel guy?’

‘Hotel guy?’ Valentine echoes, confused.

‘He said he’d come to read the meter?!’

Noel snorts, derisively.

‘The hotel guy?’ Valentine repeats. ‘Which hotel guy?’

‘To read the meter?!’ Noel rolls his eyes. ‘Are you having me on?’

‘No.’ Valentine shakes her head, defensively, then she pauses. ‘Although …’

She glances over towards the meter, frowning. ‘I’m not sure if he actually got around to …’

‘And you thought he was credible?’ Noel demands.

‘Credible?’ Valentine’s starting to look paranoid. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Did he have all the official documentation and shit?’

‘Documentation?!’ Valentine exclaims, almost irritated. ‘He came to read the meter, Noel. He was perfectly nice and polite and professional …’

‘So you saw his badge?’ Noel jumps in.

‘His badge?’

‘You checked his badge?’

‘Yes. Yes. I saw his badge.’ She flaps a hand at him, dismissively. ‘I checked his badge. Of course I did. I’m not a complete idiot. He had a clipboard and this tiny –’

‘Although an impostor could forge a badge, easily enough,’ Noel reasons.

‘You think an impostor would have a tiny torch?!’ Valentine’s almost deriding him, now. ‘And a special, little mirror inside an old powder compact?’

‘Yeah. Sure. Why not?’ Noel bristles.