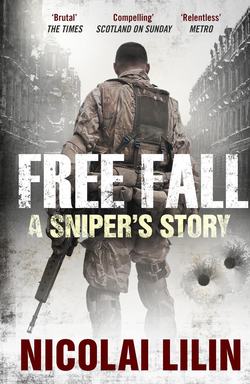

Читать книгу Free Fall - Nicolai Lilin - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWe were supposed to get there at about eight in the morning.

The spot was a couple of tree-covered hills where three huge enemy groups had set up camp a few days earlier. Figuring out how many units those groups were composed of seemed impossible; the information was pretty vague and contradictory. Different numbers came from commanding headquarters on different occasions: first it was a matter of a thousand terrorists, then fifteen hundred, and finally almost three thousand. Every hour the number went up like we were at an auction. But one thing was certain: lots of them were Arabs and Afghans, poor people recruited to fight, almost all of them drug addicts. Before going to battle they would do so much heroin that, when they ran out of ammunition, they would shuffle up to our soldiers like a bunch of zombies, their arms dangling and their eyes bulging. Those poor guys had come so far just to fight us a couple times and then die so miserably.

Their leaders, though, were professional mercenaries who had fought in several wars – in Afghanistan, in the former Yugoslavia, in all the conflicts that the Muslim world had taken part in. They were cowards, they’d take those soldiers to the battle site completely high on drugs and then abandon them. Their only interest was organising direct encounters and then vanishing, taking off. The only thing they were capable of was throwing the clueless to the wolves and making a nice chunk of change off it, which – as our captain Nosov said – ‘came straight from Red Square’.

But if those desperate men were in the hills it was because of a plan developed on the desk of one of the strategists at general command – after a month of intense fighting, our men had pushed them there. They couldn’t move quickly because the mountains started just beyond the hills, and going through the valleys in large numbers would mean incineration by helicopter fire. Therefore, the only thing the Arabs could do now was try to escape, in small groups of fifty to sixty men.

At the same time, also thanks to the decision of some genius of military strategy, part of one of our units – about sixty men from the 72nd paratroopers – had been sent by night to the area to occupy a strange, pointless position on the side of one of the hills. They were young men from the latest draft, accompanied by about ten officers and expert sergeants; they had no reserve ammunition, but in exchange they had quite a burden on their shoulders – they carried their tents and coal stoves for camp like mules. Someone had decided to transport the heavy artillery and ammunition by helicopter, to lighten their load and allow them to reach their post as quickly as possible.

Yet even that midnight, as they were crossing the first hill, a group of scouts and paratroopers ran into an enemy group. They fought a series of short battles, but unfortunately couldn’t retreat, because in the meantime other Arabs had already blocked their way from the other side. Any subsequent change in position looked more and more like a hopeless attempt to flee – they had no choice but to run, and so at five in the morning they found themselves smack in the middle of the valley, in a small young wood, surrounded by at least two thousand of the enemy.

The gunfire lasted barely ten minutes, after which the paratroopers ran out of ammunition. The Arabs, however, kept shooting at our men with mortars and launching hand grenades repeatedly and ceaselessly (incidentally, as we realised later, amidst all the chaos some of their own men had been wounded by shrapnel from their grenades). The surviving paratroopers, in the desperation of the battle, jumped into an exhausting hand-to-hand fight, using the knives and small folding blades they had on them.

But the agony of our men didn’t last long, and within half an hour they were all dead.

The signal reached us saboteurs at six in the morning. Some big shot in the paratroopers’ command insisted that the ones to go down into those mountains and eliminate the first enemy group – which had a two-thousand man cover – should be us.

Our intervention was to serve as an ‘opener’ – it was just the start to a big operation. We had to go there by helicopter, block the pass in the valley and attack them by surprise. There was only one objective, and it was very clear: ‘to eliminate all enemy human units’, as our executive orders usually put it. According to the signal, the group we were to face had left for the valley that divided the mountains and it included some professional mercenaries and commanders of military terrorist operations. The leaders, to be precise.

Some men from the armoured infantry base, at the foot of the mountains, were supposed to pick us up right after the battle was over and then the paratrooper unit would take care of the rest. In short, what they had in mind was some sort of revenge.

None of us was keen on the idea of going to fight in a place where there were two thousand enemies. We knew how things had gone in the last few hours, and we hoped that we wouldn’t end up like the others – victims of a strategical error on the part of our command. Every time we had to work behind the front lines, in enemy-controlled territory, we felt like we were playing Russian roulette.

The preparations were always the same; we had to check our weapons, ready our jackets and fill them with ammo. Usually each of us brought sixteen long magazines, four or five hand grenades and a pistol with a few spare cartridges. We never carried our guns on our belts, as is usually done; we put them under our jackets at waist or chest height, where we had hand-sewn a special pocket ourselves. It was important to have our bodies free to run and move without making noise. Before heading out, we would always jump on the spot a few times or make a few sudden moves, so we could tell if anything was loose that could make a lot of noise at the wrong moment.

Our rifles were also modified to be as silent as possible when we moved. The first thing a saboteur had to do with his Kalashnikov was saw off the little iron hooks for latching the gun to his sling. Usually the metal parts kept touching and made a lot of noise – at night, especially in humid air, that noise could be heard up to twenty-five metres away. We used the classic Kalashnikov sling – or alternatively a mountain climbing rope, the ten millimetre ones – and wrapped electrical tape around it several times to attach it directly to the folding stock and the grip, which was plastic on the new models and wood on the old ones. The tape blocked all sound, and it was very resistant. In city battles, where you always needed to have your hands free and your rifle handy, we would often tape our Kalashnikovs right on our chests, against our jackets. I always wore my bulletproof vest wherever I went – it was like a sort of underwear. I even wore it to the bathroom, whether I was on base, with my comrades, or on a mission in the middle of the woods.

Once we were ready to go, we all sat in a circle and had a few minutes of silence. It’s an old Russian tradition, called ‘sitting on the road’. They say that before embarking on any journey, or beginning anything, carrying out this simple ritual brings good luck.

Later we would be transported to wherever our assistance had been requested. Many times, we jumped out of a plane, primarily at night – that’s why our parachutes were black, and the other paratroopers called us ‘bats’. At the end of a mission, attack, or any other military operation, to show the others that we’d been the ones who took care of the mess, we would draw a bat somewhere. It was a kind of signature, a sign of recognition and valour.

The other military corps had symbols too; every wall in the cities where there had been battles was covered in tags, often along with messages. The soldiers expressed their feelings in sentences like: ‘If I die, don’t wake me up’ or ‘Once all my ammo’s gone, remember me with kind words.’

In special operations, like ambushing nerve centres or freeing hostages, our captain would leave in plain view a white glove, which was part of the uniform saboteurs wore during military parades.

That time, Nosov explained the situation to us in detail, and he figured we could even capture a few hostages because, as he said:

‘The guys up there’ – that is our superiors – ‘like to push around prisoners of war.’

We set off in two transport helicopters, plus an assault helicopter for protection from possible ground attacks. As a means of transport, helicopters, like everything in war, weren’t very safe. There was always the danger that somebody could shoot off a flare and down it, even if they crashed more often because of mechanical problems than from enemy attacks.

We reached the spot at the prearranged hour, around eight in the morning. We found a group of night explorers and special infantry units waiting for us near the woods. They were all people ruined by war – they were very cruel, and after their operations you would often find among the bodies men who’d been tortured, their fingers or ears cut off; cases of violence against civilians were frequent. Within the infantry division, dedovshchina was extremely common, even during war; the older soldiers exploited the new conscripts and would force them to go through countless humiliations. This is the reason why the infantry has always had the highest amount of suicides and deserters – many of them can’t stand the injustice, and they suffer more from that than from the reality of war.

As soon as we landed, it was clear to both groups that we would have to collaborate – the infantry, like the other units in the Russian army, weren’t too fond of us. Other soldiers were always obliged to follow the orders given by any higher-ranking official, whereas we never were. This is why we’d clashed with the officers of other divisions many times, especially the younger ones who would give us orders that we never obeyed. Our freedom from military hierarchy wasn’t liked by anyone.

As the first order of business, we set a trap for our enemies. According to command’s predictions, the Arabs would arrive around nine-thirty. We covered the positions on one side, at the point where the valley narrowed, while on the opposite side two of our men placed the anti-personnel mines and fastened hand grenades to the trees. A string was stretched taut across the ground, and as soon as someone passed by and broke it the bomb would explode.

We still had half an hour to go before the enemy’s predicted arrival, when our sentinels suddenly rushed back to us – we’d sent them to explore three kilometres ahead.

‘The column is composed of sixty-three armed men,’ said one of them, with extreme precision, ‘and it’s advancing very quickly.’

‘We saw lots of mercenaries . . .’ another added.

We were happy. Killing mercenaries meant taking home lots of trophies – American things and other various trinkets. The night explorers immediately started fighting over who would get to keep the hiking boots. Usually the Arabs wore boots produced in the West with high-quality materials, and every infantryman dreamed of having at least one pair.

The column moved along at a clip because they feared direct conflict and they wanted to get out of the area as quickly as possible.

I was positioned a little higher than the others, hidden behind a large tree, where I had established my line of fire. From that spot, the view of the valley really opened; I was able to survey almost a kilometre and a half of the area.

About fifty metres below me was the night explorers’ sniper, a professional soldier with whom I had divided tasks – he would cut off the column from behind and I from the front; that way nobody would be able to escape.

The strategy we used was very simple, and, as far as I knew, had been perfected during the war in Afghanistan, against the Taliban. On one side of the space where the battle unfolds, it’s open fire; on the other side, there are the mines. This way, the enemy is disorientated and he’s forced to move away from the bullets to find a comfortable position and respond to the fire, but he steps on a mine and blows up. A mine causes a lot more damage than any other heavy weapon, because it’s absolutely unexpected – a blow from a mortar or grenade launcher is very loud – and even if in the din of the gunfire it’s hard for the untrained ear to tell one sound from another, if you’re quick enough and hear the explosion, you can manage to avoid the worst.

For us snipers, chaos was the ideal atmosphere in which to work without being discovered. As long as the surprise-effect lasted and the enemy showed fear, we would knock down every subject that looked dangerous, like the ones with grenade launchers and heavy artillery, snipers, sharpshooters armed with rifles that had optic and dioptric devices, the soldiers with equipment to communicate with the field, the expert commanders and mercenaries, easy to recognise from the superior quality of their dress, arms and ammo. Lots of Arab commanders loved the U.S. Marines’ bulletproof vests, which were easy to spot from afar since they were less heavy and bulky than Russian ones. They always had the best weapons, usually 7.62x39-calibre AKS-47s, with American-made scopes or dioptric lenses mounted on top. They were always the first to hit the ground.

Sometimes, however, it wasn’t so easy to push men onto the mines. Lots of them tried to turn around and run or would throw themselves forward. At first you had to concentrate your fire on the first and last in line, continuing to reduce the target range but being careful not to hit the people in the middle. This way, human instinct would take over – seeing others fall dead in front of them and behind them, the men would head for the opposite side of the road, and would end up on the mines. After a while, we would also aim at those remaining in the middle, and one after the other they would all set off our fatal traps. Stepping on a mine meant blowing up on the spot.

The mines we used were in part Russian-made, in part taken from the enemy. In the Russian army, it was hard to get anti-personnel mines for normal operations; according to regulations, it was supposed to be expert military strategists who mined an area following a specific plan, established with command. The use of mines or other explosive devices was defined as ‘tactics of terror’, and since the whole world knew that we were fighting against terrorists, we were supposed to be different from them. If any enemies blew up on a mine and command asked us for an explanation, we all said they’d been put there by the Arabs – nobody could say precisely who, when, or how it had been planted.

To avoid potential problems at the administrative level, all the units would take some of the mines planted by the strategists and keep them for when we would need them. We often bartered with officers or the soldiers who ran the explosives depot; they would give us some of their stuff – mines, bombs, grenades and other explosive material – and in exchange we would bring them the weapons we had taken as trophies.

Much later, when I was back home, I was watching television when I heard a correspondent talking about how the Chechen war had been fought.

He said that the Russian soldiers had scrupulously followed the moral principles of modern war, and that in our army the use of anti-personnel mines was officially prohibited, for any military operation.

If I think of all those mines we planted that went unexploded . . . Who knows how many people still risk stumbling onto our traps.

Back to that morning when we had to avenge our paratrooper comrades . . .

After we were all in position, hidden in the thick of the woods, the only thing left to do was wait. Our ambush was ready, and before long the enemy would come. The sentry had said that the column was composed of over sixty people, whereas there were only twenty-five of us, even counting the infantrymen and explorers. But we had the surprise-effect on our side, one of the most powerful weapons in military strategy.

The first to appear was a group of five scouts; they were Arabs with long beards. They looked hastily and distractedly to the sides of the path, and continued on without stopping. We let them pass and waited for the rest of the group.

Shortly afterward, no more than three hundred metres away, the column we’d been waiting for appeared. We gave the entire group enough time to enter the valley and then, as planned, our machine gun started shooting at the last ones in the row. Those machine guns were ‘toys’ to the night scouts – they were extremely powerful weapons, beasts that could shoot up to six rounds a second; the bullets were large calibre, capable of splitting a body as if it had been chopped in half with a giant axe. We only had a light 7.62-calibre RPK machine gun, manned by Zenith. As the Arabs began to move towards the mines, our machine gunner went to work on the rest of the group.

I followed right after Zenith’s gun, aiming for the front of the line. In the first ten seconds, nobody responded to our fire; enemies fell to the ground one after another without having time to react.

Through the lens I saw human bodies disintegrate with the machine gun blasts – arms flew off, faces blew up; I shot at the torso, as they teach you to do with moving targets. After I hit them they would keep running for a couple metres and then suddenly drop, as if hit by a powerful gust of wind.

Then some of the Arabs took positions on the ground, shielding themselves behind their comrades’ bodies, and started shooting at us. The bullets went just above our heads – they were experts, they aimed towards the shells from the precision rifle my comrade in the infantry was using. He had a weapon without a silencer, whereas I had an integrated silencer and the sound produced by my rifle was no louder than a handclap. People who have grown up in war-torn areas can hear and recognise every single noise. From a mere series of blasts at several metres’ distance they can get a clear idea of the type and number of weapons, and are even able to figure out their location.

While some enemies were shooting, others began to retreat to the other side. After a few seconds the mines began to explode – two bodies dissolved instantly, sending up a little red cloud, as if their blood had turned to mist. Someone shouted something in Arabic, and everyone else who had been running towards the mined area halted in their tracks.

About twenty were still standing but they didn’t know what to do. The machine gunners had let up and our guys with normal rifles took down the enemy with precise, targeted shots. One of them started to zigzag; they shot at him several times, following his moves, but he seemed able to dodge all the bullets, he was so fast.

Just then I heard Captain Nosov yell at me:

‘Kolima, see him? Take him down, but don’t kill him!’

So I used the basic technique for catching a moving target; I aimed my rifle on his path. Even if he continually changed direction from right to left, there was a constant in his movements because he always passed through the middle. I calculated where he would pass about ten metres ahead and waited. When the objective came into a quarter of my crosshairs, I pulled the trigger. The bullet hit him at leg height, blowing off a piece of his knee. He dropped straight to the ground, yelling and flailing his arms.

‘Holy shit,’ said Nosov.

Before making a move my comrades and I waited a little, looking around, but none of the enemies gave signs of life, except the runner. He was lying in a pool of his own blood, and he was conscious. His backpack was nearby, and he was trying to grab it to get his rifle, but his movements were slow. That enormous hole in his knee must have hurt like hell.

When we went down, the infantrymen went to inspect the area of the massacre. Everything was soaked with blood and dust; our steps were heavy because we felt a swampy mass underfoot, like mud. There were body parts everywhere – arms, legs, heads shattered like ceramic vases.

We realised that one guy had survived. Miraculously, he was still alive and in one piece; perhaps when the chaos broke out he had hidden and we hadn’t caught him. Yet even if he didn’t have a single wound, he was completely disorientated – he walked in circles around his dead companions, disarmed, his hands raised towards the sky, speaking in his language with a desperate tone. He wore a military uniform with the insignia of one of the many fundamentalist organisations involved in the war in Chechnya; he had a long beard and a small cap completely covered in medals, the kind that Muslims usually wear. It struck me, because there in the woods among the corpses he truly looked out of place. I sensed that it would have been better for him if he were dead.

An infantryman seized him by the beard and with the butt of a pistol smacked him in the face. He let out a cry full of pain and fell to his knees, speaking in a feeble voice full of humility. He was probably asking him to spare his life. But the soldier kicked him again in the head with his heavy boot, and the Arab was left on the ground.

That instant, a small digital videocamera fell from his clothes. The soldier picked it up and tried to turn it on, but Captain Nosov started shouting.

‘Soldier! Who gave you permission to touch the technical evidence or mistreat my prisoner?’ Nosov was famous for picking fights with everybody; even the guys in the other units were afraid of him. The rumour was that no matter what he did he never got punished. He had fought in Afghanistan, and so for many he was a veteran worthy of the highest respect.

We ourselves had once been witness to a very personal event in his life. A young nurse, who worked on a base where we were temporarily stationed, just so happened to fall in love with him. When we transferred, as we saboteurs always did, the poor girl killed herself with an injection of morphine.

We hadn’t heard anything about this story but one day, three months later – we were on the front lines, fighting in a small city – a young investigator came from the military law office. He delivered a letter to us and started asking questions about our time on the base where the nurse had worked. In particular, he was interested in finding out whether our captain and this woman had engaged in ‘relations prohibited by military code’.

Obviously we all said we didn’t know a thing, though someone recalled Nosov coming down with something while we were stationed on the base. So – we told the investigator – a nurse in fact did come to our unit, but nobody could remember her in any detail. The investigator asked a few more questions and then left, giving us the letter. We never saw him again.

We all went together to deliver the letter to Nosov right away, and the captain asked me to read it. Before taking her life, the woman had written that she couldn’t imagine a future without Ivanisch. She called him a ‘heartless man’ and concluded by saying that he was ‘as crazy as he was handsome’.

After I finished reading – the captain had remained stock still the whole time, without batting an eye – Nosov didn’t do anything in particular. He looked at us for a moment and then whispered a single phrase:

‘If someone is weak, they should stay home.’

At his officer’s command, the soldier rushed over to our Captain, saluted him, and handed him the videocamera. A device like that must have been worth a lot, and for low-ranking soldiers could even present a risk. To prevent anyone killing them for it, officers would immediately take any object of value off their hands.

Nosov carefully opened the videocamera, turned it on, and after a few seconds called three of us over:

‘Strays, take everything out of that piece of shit Arab’s pockets and wrap it up for consignment. We’re taking him home with us . . .’

He showed us part of the film. The Arabs had captured two of our paratroopers; one already half dead, the other seriously wounded in the stomach but still alive. One Arab said something incomprehensible, and all the others started yelling and chanting religious phrases. Abruptly, mercilessly, one of them cut the heads off the paratroopers. Then they danced around with the heads in their hands, with our soldiers’ lifeless bodies in the background. One came up to the videocamera and said something in their language. Then the video broke off.

Before tying up the Arab prisoner, we inspected him thoroughly. He had a small fabric bag hooked to his belt: inside there was a portable computer, a map with some notes and a series of Afghan and Russian passports, all with different names but various photos of the same face.

Nosov was satisfied.

‘This time we got the good one . . .’

Meanwhile, the infantrymen took the shoes and other things that could be of use from the bodies. It was like being at an outdoor market – they kept shouting things like:

‘Forty-six, boys, who wears a forty-six? I’ve got a good pair of shoes here, come and get ’em!’

‘Help me cut open this bloody jacket – there’s a Colt under there, I can see the butt but I can’t get it off this fucking fatso!’

‘Hey! I’ve got two full Beretta clips! Does anyone need them?’

‘Fucking hell, this guy’s shoes were practically new and even the kind I like – too bad our guns blew all these holes in them . . .’

‘Guys! I have a cool designer* bayonet over here! Who wants to trade for a pair of shoes?’

In this way, in fifteen minutes the infantrymen had picked the dead clean, leaving them barefoot and unarmed. We’d made an agreement with the infantry; since they were only rarely involved in operations like that and they needed shoes, guns and so on more than we did, they were free to take their trophies. They would leave us the rifles, scopes and infrared laser pointers, which the Arabs had in abundance, given that the United States systematically and with great generosity refurnished them with all the necessities.

We took the new Kalashnikovs to reinforce our equipment and put everything else in a pile with a hand grenade underneath, which would render the weapons completely useless. I kept for myself a Finnish-made precision rifle, equipped with an American scope and ten full cartridges.

When we were getting ready to go back to the base, Nosov went over to the guy I had hit in the knee. He was hardly moving. His face had gone white, he was losing a lot of blood and if it went on that way he wouldn’t last much longer.

The captain looked at him with a wry grin and said:

‘You had some fun here in the valley, huh?’ He placed his foot on the wound, right where the white bone was poking out, and pushed down with brute force. The poor wretch shouted hopelessly, it seemed like he was going to explode from pain any moment. Nosov laughed softly, looking him right in the eye.

‘Piece of shit Arab, you made a bad move coming here. They told you a load of crap about the Russians . . . You think that your people killed the infidels, right?’ Nosov didn’t raise his foot from the man’s knee and his entire body was shaking. A dribble of dark spit trickled out of his mouth, as if he had eaten dirt. He didn’t have the strength to scream, he just made a quiet moan, like the cry of a sick dog. The captain pulled his knife out of his jacket, and stroked it as he continued his speech.

‘I know you think you’re going to your nice little Muslim paradise now, but you can’t be so naïve as to think that they’ll let you in without you suffering a little here on earth . . .’

We had all realised that something truly horrendous was about to happen, but we were paralysed.

A young officer in the infantry, who seemed to be the most cruel of their group, stood there like a statue; open-mouthed, as still as if he had seen a ghost.

Nosov exposed the Arab’s chest, ripping off his military jacket. The man stared at him without saying anything, his eyes bulging with terror.

‘Thank goodness I’m here, always willing to help you good people, to oil the gates of the garden of your god. So when you finally open it, it won’t bother you with its squeaking . . .’

Nosov bent over him; he put one knee on his chest, the other on his legs, then stuck the knife in his belly and began to cut.

The Arab howled so loud that his voice gave out soon after; he just let out a sort of prolonged, inhuman whistle, like a machine with metal parts grating against each other.

Our captain continued carving into his chest, accompanying his work with a song, a kind of saboteur anthem:

‘A bayonet in the back, a bullet to the heart,

the wolves will pray for our souls!

The dead aren’t warmed by triumph or glory,

Blood runs in our veins, the blood of the Russian,

today we will satisfy death, God forgive us!’

The louder the Arab wheezed, grimacing with pain, the louder Nosov sang, while he continued carving with patience and calm.

‘Born and raised there, where the others will die,

that’s why fate made us saboteurs!

The Motherland, great Russia, even she is afraid of us,

we are her true sons, for her we’d drown in blood,

but our hearts burn with true love!’

When he was finished, the captain got up slowly, and with a sadistic smile said to the rest of us:

‘We were here, the saboteurs!’

The man’s entire torso was skinless, from his navel to his neck. The Arab had lost consciousness, but you could see he was still breathing softly.

Next to him, on the ground, there was a layer of skin. Nosov had cut it in the shape of a bat, just like the ones we drew on the city walls.

The captain said to the infantrymen:

‘Go ahead and take it if you want, keep it as a souvenir. That way you can tell everyone that at least one time in your pointless lives you knew some real men . . . Remember that being cruel doesn’t mean cutting the noses or ears off the dead to make a necklace or a keychain . . . You don’t rape women or beat children. Try to look your enemy right in the eye when he’s still alive and breathing, that’s enough . . . And if you have the balls to do something else, well go ahead . . .’

We said nothing, mulling over what had just come out of our captain’s mouth. The infantrymen seemed frightened, some had stepped back, pretending they hadn’t seen anything.

The silence that had fallen around that inhuman torture was broken by Shoe. With an almost indifferent and calm expression – as if he were on vacation – he proclaimed:

‘Well, not too bad, Ivanisch, that bat almost looks real!’

A young officer from the infantry pulled his gun out of his holster and went over to the Arab, aiming at his head. Nosov gave him a dirty look.

‘What are you doing, son?’ he asked, calm.

‘Enough, I can’t take it – I’m going to kill him . . .’ The officer was shaken up. His hand trembled as it gripped the weapon.

‘This guy stays as he is,’ Nosov yelled, ‘and in fact I hope he lives till his friends get here . . . They think they’re cruel? They don’t know shit about cruelty! I’ll teach them personally what it means to be cruel!’

Then he went towards the prisoner on whom we’d found the videocamera and the passports. He was all tied up, ready to come with us. Nosov grabbed him by the beard and dragged him over to his freshly skinned companion:

‘Look, and look hard, Arab . . . You don’t know who you’re playing with! Pray to your god that command is interested in you, otherwise I’ll skin you alive and make my guys belts out of your hide!’

After about ten minutes, the helicopters came. We jumped on while the infantrymen stayed behind, waiting for two special infantry units to close off the valley.

We headed back to base, tired and loaded with useless stuff as usual, this time with an Arab prisoner to boot, who, while we were up in the air, suddenly started to cry.

Moscow, feeling sorry for him, gave him some water to drink, and the captain smiled.

‘Give him a drink; I’m sure his throat is all dry . . . What a shitty day, boys, surrounded by a bunch of homos . . .’

When we got to base, there was already a delegation waiting to pick up the prisoner.

Captain Nosov spoke to the colonel while his men loaded the Arab onto another helicopter. The colonel called Nosov ‘son’, and the captain called him ‘old man’; you could tell that they were buddies.

The colonel said:

‘The infantrymen complained, saying that you made a bloodbath, you tortured a prisoner . . .’ He wasn’t at all angry; he spoke with a mixture of complicity and irritation.

Nosov, as always, was playful and in good spirits:

‘You know how they are, old man, those guys shit themselves as soon as they get wind of an Arab . . . They need to be shown that we’re the dangerous ones – they should be afraid of themselves, not those ignorant, incompetent, drugged-out religious fanatics . . .’ Whenever he spoke, Nosov had a mysterious power; his words carried a strange certainty. The colonel thought for a moment, and then, smiling, clapped a hand on his shoulder:

‘Son, you’d certainly know better than anyone else. But remember, if anything ever happens, I’m always here . . .’

As the helicopter ascended, the colonel smiled from the window and waved. Then he made a sign on his chest, as if he were drawing our bat with his finger. Still smiling, he clenched his fist, as if to say ‘Keep it up!’ We all broke out in big grins and waved back at him, as if he were our own grandfather who had come to visit us.

I thought a lot about what happened that day. Sometimes I regretted not having killed that poor man I’d shot in the knee. But later, after some time had passed, I came to understand the insane logic that guided our captain’s actions, and I realised that, yes, it was true that he made some extreme decisions, but he did it so that we could keep fighting the war the way we did.

We owed our reputation to Nosov’s great skill in handling complex situations well in the face of the realities of war.

And if his choices didn’t always conform to human morality, it was only because they reflected the horror and the difficulty we endured every day in the war, trying to stay alive, strong and sound.

_______________

* This was what we called military supplies – ammunition, weapons, clothing – that came from a foreign country.