Читать книгу Requiescat - Nigel Barley - Страница 3

Preface

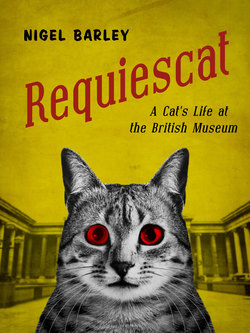

ОглавлениеErnest Wallis Budge was a real person, born in 1857 out of wedlock and into rural poverty and, against all the odds, would become a pioneering Egyptologist at the British Museum - half Indiana Jones, half Mr. Pooter - who wrote prolifically, climbed socially and numbered the rich and famous among his social set. His friend, Mike, was a real cat and a real presence at the British Museum and received more elaborate obituaries on his death in 1929 than many of the seemingly eminent staff who were his colleagues. Unfortunately, being a cat, he left no records as part of his legacy for it is not just colonised peoples, but also cats, that are the muted groups of museums and the history they tell. Yet, institutions often show their most human face in their treatment of animal staff and, upon this basis, I have constructed a work not of pure but rather impure fiction where many of the events described are documented as happening, even if the fine detail escapes us, and all the strange and exotic objects mentioned as making their way, by the most diverse paths, into the collection, are also real. Inside the museum, they continue to pursue their own careers from one century to the next and occasionally erupt into the popular imagination and works such as this. To write a book of this nature is to cook a complex dish that cannot easily be teased back into the meat-and-two-veg of everyday truth and untruth and the linking together of disparate threads may or may not correspond to what actors saw as happening at the time. Most liberty has been taken with strict chronology so that some events have been stretched while others have shrunk. Thus, Sir Fredric Kenyon did not assume the grandiloquent title of ‘His Majesty’s Gentleman Usher of the Purple Rod’ until 1918 but I anticipate that elevation by a year or so and it seems unlikely that Budge and George Bernard Shaw overlapped as lovers of Edith Nesbit in time as well as space but authorial economy certainly demands it. As Edith herself pointed out in The Amulet, time is largely a state of mind. The institution described in the final chapter is clearly an entirely imaginary construct.

Budge adored the Savile Club and his friendships with some of the most famous writers of his day that were cemented there. For much of the public, he was the face of British Egyptology at that time, far more accessible and benign than the superciliously academic Flinders Petrie, for museums then had already begun to play the same Janus role of mediators between specialism and general knowledge that they do now and that relationship was just as uncomfortable and contested as it is today. His friendship with Dorothy Eady alias Bentreshyt alias Omm Sety, who became one of the most colourful and extraordinary figures of Egyptian historical research, is but one example of his accepting nature and the ways in which he did his bit to spread awareness and sympathetic understanding of his subject, regardless of academic niceties and the enforced sobriety of official museum space. Budge’s career benefited from high patronage without which he would never have been able to overcome the disadvantages of his birth but he also became embroiled in academic feuds of great bitterness that continue to undermine his professional reputation and it is to his disadvantage that his obsession with collecting became politically unfashionable. As an affectionate memoir, it is to be hoped that Requiescat may do some little to redress that.

Many thanks are due to Museum staff for their generous help. They had best remain anonymous but know who they are. My gratitude is profound and sincere. Mistakes remain my own and could even be deliberate falsehoods. After all, a cat cannot be expected to know everything.

Nigel Barley