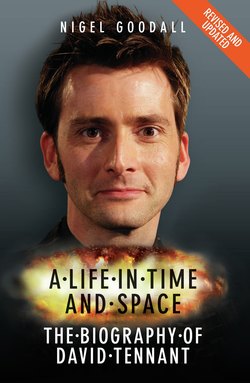

Читать книгу A Life in Time and Space - The Biography of David Tennant - Nigel Goodall - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE BOY FROM THE HIGHLANDS

Оглавление‘I was blessed with a very good upbringing, because my parents are very moral, Christian people, but without all the brimstone and thunder nonsense.’

(David talking about his childhood – 2000)

Three-year-old David MacDonald was watching Doctor Who on television and he was just crazy about it. In the years to come, he would own a Tom Baker doll, have his gran knit him a multi-coloured scarf so he could run around the garden pretending to be the Time Lord and pen a school essay declaring that he would one day play the leading role.

Although many would regard a career decision slightly premature at the age of three or four, David knew, even then, that all what he ever wanted to do was to become an actor: ‘I just loved watching people on the telly. I think I had a conversation with my parents about who these people were in the TV, and as soon as I had an understanding that this was a job, that people got paid for telling stories, that was what I wanted to do.’

Looking back, it was obvious that it was Doctor Who and in particular, Tom Baker (David’s all-time favourite) that triggered his desire to become an actor in the first place, and as far as he can remember, he was never dissuaded from pursuing his goal: ‘My parents expected I would grow out of it. And when I didn’t grow out of it and continued to pursue it, they tried to gently suggest some other things I might want to do. They always said, “You’re going to do what you want to do.” But in pragmatic terms, it’s a fairly stupid career. I think it’s one of those things you end up doing because, for whatever reason, you feel you have to. And you feel you can’t do anything else.’

As a sign of things to come, Jon Pertwee was in his second season of playing the Doctor and was only three years off regenerating into Tom Baker in the ‘Planet of the Spiders’ episode when David John MacDonald was born on April 18, 1971 in Bathgate, a post-industrial Scottish town in West Lothian, located between Glasgow and Edinburgh. That regeneration scene was the first time the process had been seen on screen. Suffering from fatal radiation poisoning, the Doctor is left for dead before regenerating into his fourth incarnation before viewer’s eyes, rather than just taking on a different appearance as had happened with the first three Doctors.

Before all of that, of course, and before David got hooked on the programme and, like the rest of the country, ranked Baker as the most quintessential Doctor ever, he spent the first three years of his life with his older brother and sister, Blair and Karen, living in Bathgate before the family moved to Paisley in Renfrewshire. His mother Helen was a full-time housewife, and his father Alexander (‘Sandy’ for short) was a minister in the Church of Scotland.

But to David, religion remains at best an abstract concept: ‘I don’t think, just because I’m the minister’s son, that I must believe. My parents allowed me to come to my own conclusions. Let’s face it, organised religion, especially in Scotland, leaves a lot to be desired and the Church of Scotland in particular has a lot to answer for. But I think I have a humanist outlook because of them – Christian in the right way.’

Sandy and Helen met at St George’s Tron Church, Glasgow in 1961 when Helen was twenty-one. Shortly after that fateful meeting, she had to go into hospital and Sandy visited her there, taking along a bouquet of white tulips as a get-well gift. But according to the Very Reverend Dr James Simpson, who is today a chaplain to Her Majesty the Queen, and who conducted Helen’s funeral service at Renfrew North Parish Church in the summer of 2007, ‘Helen’s mum was already in the infirmary, speaking to Helen, when Sandy came in with his flowers. Like most men, Sandy was a bit embarrassed about carrying the flowers, so he dropped them by the bedside and rushed out of the hospital. Helen’s mum told her: “That young man is serious about you.” And, soon afterwards, she and Sandy were married.’ Interestingly enough, those happy days of Helen and Sandy’s romance were poignantly remembered at her funeral by a beautiful bouquet of white tulips – just like the ones Sandy had courted her with – which lay on the communion table throughout the service.

Although the MacDonalds had ‘gypsied’ around other places in Scotland while Sandy worked for the ministry, they ended up making Paisley their home just three years after David arrived into the world, and to all intents and purposes, that is where he spent his childhood and where he was educated, first at Ralston Primary, followed by Paisley Grammar School, where he is said to have enjoyed a fruitful relationship with his English teacher, Moira Robertson, who was among the first to realise his true potential. Overall though, David remembers enduring academic studies rather than enjoying them.

What he perhaps enjoyed most was talking to his mates about wanting to become an actor and how he really wanted to play his hero, Doctor Who, which in his estimation was Tom Baker. Not even the emergency surgery that he had when he was nine years old, which left him battling for life with appendicitis, would deter him. ‘It was certainly touch-and-go for a while,’ recalls his friend Innes Smith: ‘It was feared he might not make it.’ On leaving the hospital, a few weeks later, he needed two months off school to allow time to recover.

It was in the period soon after the appendix scare that some pupils at his school wondered if he may be gay. He always clowned around, in and out of class, and was even a bit camp, remembers Carol Robertson: ‘Loads of girls fancied him, but he didn’t have many girlfriends. And so, some boys started to accuse him of being gay. But he didn’t care.’ And why should he? He’d already experienced his first kiss in primary school, the year after he had been signed off sick from school, with a girl called Melanie Hughes.

But that, according to David, was about four years before he started ‘really’ getting into music for the first time. He got into lots of Scottish groups such as The Proclaimers (still his all-time favourite band), Deacon Blue, Hipsway, The Water Boys, Hue and Cry: ‘I loved all that white-boy soul thing that was going on. And also the good stadium stuff, Simple Minds and U2. I guess I was also going to the theatre for the first time, going to the Citz in Glasgow. It was an extraordinary artistic policy which they operated under; I saw some of the worst things I’ve ever seen and some of the best. The first thing I saw, I think, was School for Scandal, but an unusual, high-camp production. Brilliant! Macbeth set in a spaceship was probably the low point.’

The Citizen’s Theatre, or the Citz, as David called it, was then, as it is today, Glasgow’s very own theatre. It is what it says it is – a citizen’s theatre in the fullest sense of the term. Established to make Glasgow independent from London for its drama, it produces plays which the Glasgow theatre-goers would otherwise not have the opportunity of seeing. Internationally renowned for its repertoire, it is one of few theatres in Scotland to produce its own work. By inviting a diverse range of touring work into the theatre, offers a powerful mix of productions that seal the Citizen’s reputation as the place to see theatre in Glasgow.

David balanced his theatrical and musical diet with books and movies. One book that was a favourite was J. D Salinger’s immortal The Catcher in the Rye, a novel that assumed an almost religious significance to the counterculture generation, some of whom were known to speak only in quotations from the novel. The book still resonates with readers today. Mark Chapman, the murderer of Beatle John Lennon, is one of the most notorious readers of the book. He was carrying a copy when he was arrested soon after he had shot five hollow bullets from a .38 revolver into the back of Lennon at around 10.49 p.m. on 8 December 1980, outside the Dakota Building in New York, where Lennon shared an apartment with Yoko Ono. Chapman was still reading passages from the book when the police arrived. He had apparently bought a copy of the novel from a book store in the city early that morning, a paperback edition, inside which, he scrawled ‘This is my statement’ and signed it ‘Catcher in the Rye’.

Equally influential on David, albeit for different reasons, was actress Audrey Hepburn. ‘Although I’ve seen lots of her films and am a great admirer of what she does, the little shrine in my head is to Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly. I must have been in my late teens when I first saw Breakfast at Tiffany’s.’ From an early age, he was in love: ‘She has such an iconic look: the little black dress, the cigarette holder and the coquettish grin. It’s a proper piece of good acting rather than the sort of slightly frothy, rom-com performance we often saw her do elsewhere. She brings that delicate, demure, butter-wouldn’t-melt quality to every part, and suddenly she’s playing this character who is quite dark and a bit of a loony. Yet she carries it off so assuredly you’d sell your children to get to spend some time with Holly Golightly, even though you’re aware she’d be a high maintenance nightmare.

‘If nothing else,’ he continues, ‘Hepburn makes her utterly alluring and fascinating. It’s one of the great things about movies that we’re allowed to indulge little fantasies about people that in life we would steer away from. She was a proper movie star in a way we’re not really allowed to have these days because they have to be so exposed, and we have to know everything about them. And she was probably the most beautiful woman who has ever lived, which always helps.’

Like most of us, David probably has a mix of good and bad memories of his school years. Almost certainly, the worst times for him were the days spent at Paisley Grammar: ‘I hated school, and I hated my teenage years.’ The only anecdote he offers up from this period, without detailed explanation, is the night when he was beaten up. His attackers decided he was a Goth and pounced. The bullies left him to make his own way home after he was assaulted. In fact, his only fashion crime was wearing a bootlace tie in the style of Bono: ‘I was spotty with greasy hair and pretty pissed-off; I couldn’t wait to get to drama college so that my life could get going.’

Situated on Glasgow Road, Paisley Grammar was a non-denominational state school, which had also earned itself a bit of notoriety in 1986, the year before David left. The school was threatened with imminent closure by Strathclyde Regional Council until Margaret Thatcher, then Prime Minister, personally intervened to ensure its survival and subsequently changed the law so that local councils could no longer close schools which were more than 80 per cent full without the approval of the Secretary of State for Scotland. Naturally, the council had to abandon its plans.

Not that David had much of an interest in anything to do with politics at the time, nor with Scotland. For him, his birthplace was pretty much on an abstract concept: ‘I’m very aware that Scotland is where I’m from,’ he once noted. ‘But I had no relationship with Scotland when I lived there. I had no interest in nationalism, no interest in Scotland’s nationhood or legacy, or any of that stuff until I moved down to London, which is a terribly crass, idiotic thing to say, but it’s true. My family are mostly still in Scotland, so it will always be part of who I am and what I go back to.’

But there was more to his roots than just Scotland as he would discover when he took part in September 2006 in Who Do You Think You Are? – the BBC’s ancestry series that looks at family histories of the famous. As Sarah Williams, editor of the accompanying magazine, pointed out, the episode featuring David Tennant was fascinating because it opened up a colourful and sometimes disturbing Irish heritage.

Indeed when David started filming the programme, not only did he want to untangle his Scottish roots, but also to find out about his family in Ireland and what lay behind his grandmother’s strident Protestantism. ‘I guess as you get older and you look forward to the ultimate grave, you begin to become a bit more aware of your place in the scheme of things,’ he conceded.

The first surprise for him came when researchers uncovered the details of the Scottish side of his family. For a start, he was no native Glaswegian. His great grandfather Donald McLeod was an immigrant to the city from the Isle of Mull. ‘I’ve always thought of myself as a lowland Scot. The Highlands was something that I knew was there, but I’d always felt a bit of a fraud, claiming to be part of them so that was interesting to learn,’ he said. ‘I was keen to find out why Donald left Mull when he did, and what life was like for him – whether he left because country life was untenable or whether he came to Glasgow because he thought the streets would be paved with gold.’

The truth about Donald’s motives, when it emerged at the end of one of Mull’s winding country roads, was more tragic than he could ever have imagined. His family roots lay in a series of small, ruined cottages on a wind-washed hillside overlooking the sea, where Donald was one of ten children forced from their homes during the Highland Clearances in the early nineteenth century. This was the burgeoning industrial age, with wool and meat becoming valuable commodities in the new mill towns, when many highland landowners realised sheep were more profitable than tenant farmers. So they suddenly increased the rents and when tenants such as Donald’s parents couldn’t afford to pay, they forced them off their land and often burnt their homes to prevent them returning.

‘It’s the inhumanity of it that’s quite bewildering,’ David concluded. ‘That people could do that to one another. There’s also something about going and standing where it happened that brings it all home in a way that the history books just don’t. There’s something about seeing your mother’s maiden name connected to it at such close quarters – it’s quite grim, really.’

The most positive thing to come out of the trip was that when Gregory Doran, the Royal Shakespeare Company’s chief associate director, watched the programme and saw David hold up and contemplate a skull exposed by renovations in the church where Donald was baptised. He was so impressed that he offered him the role of Hamlet. ‘It was like an audition,’ admits Doran, who immediately sent him a text asking him outright if he had ever thought about playing Hamlet. ‘He said that the two roles he really wanted to do were Hamlet and Berowne in Love’s Labours Lost. [And as] I had already decided that I would be directing Love’s Labours Lost, I thought it was an extraordinary coincidence.’

David’s Irish connection began when his grandfather Archie, former captain of the Scottish youth football team, was signed up to play for Derry City soon after he arrived in Londonderry in 1932. By all accounts, he was a stellar success, scoring 57 goals in one season – a record that still stands today – and marrying a local beauty queen.

‘Archie,’ he continues, ‘must have had a whale of a time. He must have thought he was in God’s own country: he was a superstar and was dating a beauty queen. I’d never been to Londonderry before. I just grew up with all the reports of violence, but it seemed like such a beautiful spot, you can’t quite imagine it’s also a violent place.’ But a violent place it was, and his family was at the centre of the sectarian struggle that has, in many ways, sadly come to define religion.

Fiercely proud Protestants, his great, great grandfather James Blair was an Orangeman and Unionist councillor. His great grandfather William was also an Orangeman and many of his family were among the 500,000 who signed the Ulster Covenant in 1912, a thinly veiled threat of insurrection if the British Government consented to Home Rule in Ireland.

Despite there being almost twice as many Protestants as Catholics in Northern Ireland due to their historical allegiance to Britain, the Protestant Irish had most of the land, money and good jobs; they also used vote-rigging – or ‘gerrymandering’ – to maintain the status quo. David’s own family was a proud supporter of that system: ‘My knee-jerk reaction was one of horror,’ he said. ‘I know that I’m not really qualified to judge but it doesn’t really sit with my Guardian-reading liberalism. To me [the Orange Order] is a symbol of aggression, and certainly not of outreach and peace among men. It’s quite difficult to reconcile that with the lovely people I met in Londonderry, even with my Grandad and Grandma.’

Despite his political affiliations, David’s ancestor James Blair was considered something of a radical and dubbed ‘a Guardian of the Poor’ in a local paper. He was dedicated to social justice, fighting for better homes and wages for workers. His daughter Maisie married a Catholic, Francis McLoughlin, and their son Barry was an instrumental figure in the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, taking part in many marches, including those of Bloody Sunday, and helping to challenge discrimination against Catholics. He also stood for election for the non-sectarian Labour party and was committed to the peaceful resolution of Ulster’s problems.

‘You want your family to be people you admire,’ says David. ‘Looking at James Blair, the whole dichotomy is there. Some things he did were admirable, yet he was mired in sectarianism. But I want to believe in what Barry believes in. I was proud to hear him talk about his ideas and his principles and [to] hear how he stood firm against becoming involved in violence, and it was good to leave a city that finally – despite everything – feels full of hope.’

He himself had that same kind of hope years earlier, when after leaving Paisley Grammar, at the age of seventeen, he successfully gained a place at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, where he studied for a B.A. in Dramatic Arts, which covered every aspect of producing a show, whether it was for television or theatre. As part of the two-year course, the boy who wanted to be Doctor Who would learn all there was to know about movement, vocal projection, make-up, directing and stage management, and when he was through, he would be ready and qualified to go into teaching or serious acting. Even though David loved the all-consuming nature of drama school, as everyone now knows, he decided to go for the acting option: ‘I liked having to fit everything in and juggling maybe three or four parts at the same time. Being slightly too busy all the time is energising and inspiring, and it was a great experience, especially because I was so green.’

It was also during his spell at drama school that he changed his name, not by choice, but because he had to – already there was a David McDonald on the Equity books. Almost by accident, he came across his new surname: ‘I was on the bus looking through Smash Hits and I saw [Pet Shop Boy] Neil Tennant. I thought it would be a good name as it’s got a good number of consonants in it,’ he jokes. Not that his parents would agree. In fact, his mother wasn’t at all happy about the name he had chosen. She would have much preferred it, had he taken her father’s name, McLeod, or that of her mother, Blair. ‘But at sixteen,’ says David today, ‘I wasn’t having any of that.’

On leaving drama school in 1991, having already grabbed for himself a leading part in The Secret of Croftmore for ITV’s ‘Dramarama’ series, he moved onto repertory theatre, went on tour, and in between travelling the width and breadth of the Scottish Highlands, made periodic attempts to win a part in ITV’s Taggart, a goal he somehow never managed to achieve. ‘I’m the only Scottish actor alive who hasn’t been in Taggart,’ he laughs. ‘Some people have been in it five times, playing three different murderers.’ To overcome any disappointment he felt for not getting through any of the sixteen Taggart auditions he went for, he plumped for making his professional debut with the 7:84 Scottish Theatre Company in a touring production of The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui.

‘The 7:84 company,’ David explains, ‘was formed by John McGrath in the 1970s and is still going strong. It takes two or three shows a year on one-night-stand tours around the Highlands and Islands, stopping longer in the larger towns. I went for the audition just after graduating from the Royal Scottish Academy, aged about twenty – a single-minded youngster, I had started there at the tender age of seventeen – and landed the part of Giri the hitman, my first professional part. I think there can have been only about six of us in the production – I suspect for monetary reasons, rather than artistic ones. Arturo Ui was one of those Brecht plays with thousands of characters. Inevitably, we shared them all out, with the help of a few wigs and fake noses. It was great fun, we were all young and up for it. Three of us had been at drama school together and I was terrifically excited. I was fresh out of college and really rather green, but I was earning a proper wage and having enormous fun touring Scotland in a small van. ‘Our first stop was Motherwell Civic Hall and the first performance was a disaster. We hadn’t had time to finish the technical rehearsal, let alone attempt a dress rehearsal. We might have managed, had the production not been so complicated but we were a group of travelling players who unpacked and made themselves up on stage, so of course everyone was changing, swapping props, losing props and mislaying wigs. It was utter chaos on stage as we struggled past the point at which we had ended the technical run. I remember thinking at one point: “This is my professional debut, and it’s all falling apart.” But we got through it. It may have been rusty and received terrible reviews, but the whole thing had a vibrancy and energy that I adored. And of course, I thought we were excellent.’

Not so excellent was the scathing review he alone received for his second job, playing King Arthur in Merlin in Edinburgh. Writing for The Scotsman, one theatre critic was particularly chastening: ‘The cast of eighteen are uniformly excellent with the exception of David Tennant, who lacks any charm or ability whatsoever.’ Even though he was pretty much floored by the review, it still wasn’t enough to put him off acting, or indeed, his goal of becoming Doctor Who. In fact, it was not long after the Edinburgh episode that things began to turn around when David headed down to London and moved in with comic actress and writer Arabella Weir.