Читать книгу Bali Morning of the World - Nigel Simmonds - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

"The road ran on and on, a wide avenue between stone walls. Everywhere temples lifted their stone gates, carved as feathery as the banyan trees above them. The villages were miles of walls, thatched against the rain, with hundreds of prim pillared porticos, and groups of damsels sitting by them. Beyond those parapets were homes. What sort of people lived there? What manner of life did they lead behind their sheltering barriers?"

Hickman Powell,

The Last Paradise, 1930

For four years I have lived in Bali. I arrived on holiday with very little knowledge of the "Island of the Gods"—when I stepped off the Garuda jumbo jet in October 1992 I knew next to nothing of its religion, had only a vague conception of its immense beauty and no real understanding of the extraordinary manner in which its people organize their lives. Today I feel lucky to have experienced an island which remains remarkable in a thousand different ways.

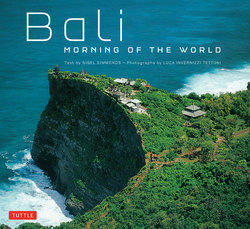

I knew this much at that time: many before me had been charmed by Bali's powerful magic. Hickman Powell, a 1930s visitor, called it "a vast spreading wonderland" and "the embodied dreams of pastoral poets". To the writer and musicologist Colin McPhee, another early fan, it exhibited a "golden freshness", where everyone was either a dancer or an artist. Pandit Nehru— India's first prime minister—immortalized the island in the 1950s when he called it the "Morning of the World" a kind of tropical Garden of Eden where, according to another early description, "care-free islanders" lived as "happy as mortals can be". Could Bali really be this good, I wondered?

The lotus, the frangipani and an ornately carved temple gate in Ubud... a heady trinity which many believe still puts Bali above other Asian destinations.

Pura Ulun Danu Bratan, the temple of the Lake goddess near Bedugul in north Bali.

I began to find out on my first visit. Setting off from the artists' town of Ubud in the grassy central lowlands, a companion and I drove through the glaucous pre-dawn twilight to watch the sun rise over Mount Batur. As we emerged onto the lip of a long-defunct crater, within which stretched a vast volcanic valley, a single purple cloud hovered over a glassy lake like a fanciful addition to an already celestial scene. And then the sun exploded above us in a blush of soft carmine hues, and I was torn between a feeling of magical wonder, of being present on the day the world was born, and an idea of what it must be like to spend a lifetime blind, and then see colour and shape for the first time. "What is this place?", I remember thinking.

As if we needed more, the island handed us an even greater spectacle. Driving back to a recently rented thatched house in the rice fields, we were greeted by a pageant of colourfully costumed worshippers tripping their way through the dazzling green landscape to a twirly-edged temple in the distance. Dressed in white and yellow, hot orange and bright blue, a magnificent parade of Balinese women walked in front of an ornately carved golden sedan chair, its occupant a boy of no more than 10 years.

Behind this little king, with his adult gaze and regal persona, trouped brown-skinned and black-haired men, their features smooth and manner proud. And then more—a line of teenage girls, a vision of collective beauty descending in size right down to a last little toddler, a perfect copy in miniature of the first skinny, bejewelled girl. We sat entranced in our jeep on the side of the road and were captivated by the beat of Bali's hypnotic drum.

As life progressed I learned more about the culture of Bali. I learned that children were carried everywhere, held in the protective arms of a family member until three months old. I listened as a priest, dressed in white, chanted a mantra in an ancient language, and watched while an entire village clasped its palms together in prayer. I marvelled at the vibrant offerings prepared for the temple, and the simple gesture of a welcome smile. I saw dance and dramas to evoke the spirits, and shadows that fired the imagination. I learned to love the island.

Festival offerings for the gods.

Bali's rugged eastern mountains viewed from Kintamani.

These days, I understand Bali a little better than I did on that first early morning in Batur—like a wised-up city boy initially enamoured with the country farm, I now recognize an earthly pragmatism which goes beyond the geographic splendour of rural living. Life is not easy for everybody on Bali. Their deep and sensual religion offsets the daily hardship of a lifestyle that in many quarters remains largely unchanged since the 17th century. Yet I continue to recognize within the culture an extraordinary sense of community, one which transcends our Western ideals of liberty and individualism and puts cooperation above competition. This, perhaps more than anything else, is the real substance of Bali's beauty. It is an island populated by a people who know how to live together. Few cultures can say the same, even though many may try.

Jukung - traditional Balinese fishing boats.

"No feast is complete in Bali," wrote the Mexican expatriate Miguel Covarrubias in 1937, "without music and elaborate dramatic and dance performances; no one would dream of getting married, or holding a cremation, or even of celebrating a child's birthday, without engaging troupes of dancers and actors to entertain the guests and neighbours." Dance and drama remain central to the Balinese way, colourful spectacles in the life of the culture. In fact Covarrubias and his wife became such enthusiastic theatre-goers during their time on the island they "sometimes had to make a point of staying home to catch up with lost sleep". The Mexican chronicler wrote in his still definitive book, Island of Bali: "Even the tired peasant who works all day in the fields does not mind staying up at night to watch a show, and the little children who invariably make up the front rows of the audience remain there until dawn for the end, occasionally huddled together taking naps, but wide awake for the exciting episodes of the play." Next to having good orchestras, a fine group of dancers is an imperative need for the spiritual and physical well-being of the community. When a society has enough money for the elaborate costumes needed for public appearance, the village banjar or community association gives an inauguration festival to bless the clothes. All actors, dancers or story-tellers undergo the same ceremony—in the case of a dancer, a priest uses the stem of a flower to inscribe magic syllables on the face, head, tongue and hands in order to make the dancer attractive to the eyes of the public. It is not only on this occasion that dancers pray for success; before every performance they make small offerings to the deities of the dance.

The legong, for which this girl is dressed, is often said to be the finest of all Balinese dances. Three little dancers, usually portraying an air of infinite boredom, sit on mats in front of the orchestra. They are dressed from head to foot in silk overlaid with glittering gold leaf and on their heads they wear great helmets of gold ornamented with rows of fresh frangipani blossoms. The girl who sits between the two legongs, their attendant or tjondong, waits until the moment is right, then to the accompaniment of the gamelan orchestra gets up lazily and stands in the middle of the dancing space. "Suddenly," writes Miguel Covarrubias, "at an accent from the orchestra, she strikes an intense pose: her bare feet flat on the ground, her knees flexed, she begins a lively dance, moving briskly, winding in and out of a circle, with an arm rigidly outstretched, fingers tense and trembling, and her eyes staring into space. At each accent of the music her whole body jerks; she stamps her foot, which quivers faster and faster, the vibration spreading to her thigh and up her hips until her entire body shakes so violently that the flowers of her headdress fly in all directions. The gradually growing spell breaks off unexpectedly and the girl glides with swift side-steps, first to the right, then to the left, swaying from her flexible waist while her arms break into sharp patterns at the wrists and elbows. Without stopping, she picks up two fans that lie on the mat and continues dancing with one in each hand, in an elegant, winding style."

Images of Bali, a kaleidoscopic culture where children are reserved a special place close to the gods.