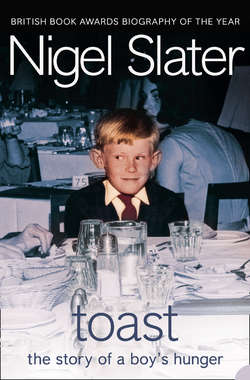

Читать книгу Toast: The Story of a Boy's Hunger - Nigel Slater - Страница 34

Crisps, Ketchup and a Few Other Unmentionables

ОглавлениеI am not certain everything is going well at Dad’s factory. He’s been quiet lately, pensive, distant, coming in tired and late. I heard him use a low, angry voice on the phone the other night. Another night he looked crestfallen when I went into the kitchen to say hello to him. Like I was a nuisance. He hasn’t let me sit on his lap for weeks. ‘Not just now,’ he says.

He spends a lot of time in deep discussion with my mother and when he laughs it is like he cannot stop, then ends up with tears rolling down his cheeks. After that his mood changes and he lets me climb up on his lap.

My father and his partner Joe Ward built that business up from nothing, taking over a vast disused munitions factory and turning it into something of a gold mine. He employed about twenty men in the factory, a secretary and a clerk who did ‘the books’. There used to be an air of excitement, a barely hidden pride about how well the business was doing. He seemed to come home weary now, like he had had enough. Two years earlier, he had been investigated by the Inland Revenue for selling scrap metal from the factory, offcuts mostly, for cash. After that there was more bookwork, so much so that he and my mother used to sit for hours in the kitchen, the table barely visible under piles of receipts on wooden spikes and long hardback books with endless columns of figures and swirly, Florentine endpapers. The two of them could be there all evening, my mother on one side of the table, him on the other. Sometimes he would come and take the whisky bottle and two glasses from the bookcase-cum-drinks cabinet.

I remember one night – they had just started doing ‘the books’ at home – when I saw something on television about President Kennedy being shot. I went in to the kitchen to tell them he was dead and they told me not to make up stories. ‘But it’s true, it’s on the television,’ I pleaded. My father threatened me with a good hiding if I didn’t stop telling tales.

‘I’m sorry, darling,’ Mum said when she came into the sitting room and saw the news unfolding on the television. She just stood there, her hand clasped to her mouth, gasping, ‘I just can’t believe it.’

‘I told you,’ I said, hot and frustrated that they hadn’t believed me.

Half an hour later my father came in with a packet of crisps. ‘Have these,’ he said. It would be the nearest I would get to an apology. Crisps were frowned upon, rather like baked beans, chips and Love Hearts. Occasionally, he would bring some back from the shops, and I’d open up the crackly bag, poke my fingers right down into the crisps and pull out the bright blue twist of waxed paper that held the salt. Unfurled and shaken into the bag, it was important to get as little of the salt as possible on the crisps. That way, when I had scrunched all the crisps I would have the bonus of finding a thick line of salt at the bottom of the bag to dab up with a wet finger. The salt and the few little crisp crumbs among it were a treat beyond measure, better even than the crisps themselves. This sort of eating wasn’t banned, it was simply disapproved of. That was enough. Crisps – light, salty, golden – were banished for the same reason that baked beans were, and fish and chips in newspaper, mushy peas, evaporated milk and sliced bread in plastic. It wasn’t that such things were considered bad for me, too sweet or full of additives. It wasn’t even because they didn’t stock such things at the local grocer. It was because my parents considered them to be ‘a bit common’. The same way they thought petunias and French marigolds were common. The way they thought flip-flops or girls who didn’t tie their hair back were common. The same way they considered eating the top layer off a Bourbon biscuit and licking the chocolate filling off was common. Quite how they explained away their predilection for tinned mandarin oranges and Kraft cheese slices is a matter for speculation.

The flip side of their snobbery was that we mostly got to eat good ham, sliced from the bone at Percy Salt’s on Penn Road, and to drink Maxwell House coffee. We bought bread from a proper baker’s, albeit a white sandwich loaf which my mother found easier to slice that the cute cottage loaves with their wayward topnot. Fish came from the fish shop rather than in breadcrumbed sticks (I didn’t taste a fish finger till I was nineteen) and we bought Cadbury’s chocolate MiniRolls rather than a plain Swiss roll. We had Battenberg too, and fresh cream and sponges on Saturdays and sometimes waxed cartons of trifle.

Some things were quite unmentionable, even in hushed tones. Babycham, sandwich spread, tomato ketchup, bubblegum, HP Sauce and Branston Pickle could never even be discussed let alone eaten. Those chocolate marshmallows with biscuit and jam in the middle that came in red-and-silver foil (and which I could cheerfully have killed for) would never have been allowed past the front porch.