Читать книгу Driven toward Madness - Nikki M. Taylor - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

“HOPE FLED”

Then, said the mournful mother,

If Ohio cannot save,

I will do a deed for freedom,

Shalt find each child a grave.

I will save my precious children

From their darkly threatened doom,

I will hew their path to freedom

Through the portals of the tomb.

—Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, 18571

Late in the evening of 27 January 1856, the Garners—an extended family of eight people living on two farms in northern Kentucky and ranging in ages from nine months to fifty-five years—escaped from slavery. The fugitive family included twenty-two-year-old Peggy Garner, who was pregnant; her twenty-seven-year-old husband, Simon Jr., also known as “young Simon”; their four children, Tommy, Sammy, Mary, and Cilla—who were almost six, four, and two years, and nine months old, respectively; and young Simon’s parents, Simon and Mary, both in their midfifties. Peggy and the children were owned by Archibald K. Gaines of Richwood, and Simon Jr. and his parents lived roughly a mile away, on a farm owned by James Marshall. What made the Garners unusual is not that they escaped slavery, but that they did so as an intact family unit.

Thousands of enslaved people attempted to escape slavery every year in the antebellum era (roughly the years from 1830 to 1860), but only a small fraction succeeded. Coming up with a plan of escape, including the means and route of escape, was incredibly challenging for enslaved people. Even a solid escape plan often was not enough to guarantee success; would-be fugitives had to summon a high degree of courage to face the prospect of permanently leaving behind their farms, families, and communities in pursuit of an uncertain freedom in an unknown region. Only the most ingenious, resourceful, determined, courageous, and fortunate fugitives made it to freedom.

Despite how courageous, empowered, resourceful, and determined the Garners were, and how intensely they desired freedom, the sheer size of their party proved to be a hindrance. Larger groups, with few exceptions, rarely made it to freedom. The larger the group, the greater the risks of discovery and capture.2 Most potential runaways knew the risks and would not dare attempt to escape with their entire family in tow. The Garners were an exception.

Not only were entire family units unlikely to escape slavery, but even as individuals the Garners were the unlikeliest of runaways. Most runaways tended to be young men in their teens and twenties, traveling alone. None of the Garners fit that profile except Simon Jr. In their mid-fifties, young Simon’s parents were the antithesis of that youthful profile. Peggy was well into her fifth pregnancy and certainly could not have made the journey without the assistance of her family. As women and mothers, Peggy and Mary were far from typical runaways, as well, because enslaved women did not commonly try to escape slavery. It is not that these women did not want to escape, but because they were the primary caregivers for their children, the thought of leaving them behind was unimaginable; the thought of taking the children with them was equally overwhelming. In other words, children decreased the likelihood that their mothers would escape. Interestingly enough, although women did not escape bondage as often as men, most of those who did were driven out of a fear of losing their children through sale, and those took the children with them.3

Gender ideals and obligations to family and community kept enslaved women tied to their farms and plantations. Ideals about black womanhood pressured women not to leave their children behind if they did flee: the culture dictated that mothers should be selfless and sacrificing. Good mothers, then, did not abandon their children, just as good wives did not abandon their husbands, on a quest for personal freedom. Additionally, enslaved women had fewer realistic opportunities to escape because of their relatively limited mobility. Nineteenth-century gender conventions limited the movements of enslaved African American women and confined them where they lived and worked. They were subjected to what the historian Stephanie Camp termed a “geography of containment.” The only exceptions were those women who traveled with their owner’s family as personal servants or nurses. By comparison, enslaved men possessed far more mobility than enslaved women: they transported products to the market, did errands, carried messages for their owners, worked in cities, and sometimes worked jobs for pay. Moreover, they were more likely to be given passes to visit family members. Enslaved women’s geography of containment was certainly true for the Garner women. Peggy claimed she had been to Cincinnati only once—as a small girl—underscoring how little mobility she had had in her entire life. Mary Garner had been hired out once about five years before the escape; she then spent a year hired out to a man named Cas Warrington, of Covington, Kentucky—a small town just across the river from Cincinnati. During her service to Warrington, Mary enjoyed mobility for the first time in her life. He often sent her to Cincinnati on errands and allowed her to travel there by herself to attend church services. But it had been years since she had enjoyed that mobility. By contrast, young Simon had been hired out several times and had frequently traversed Boone County, northern Kentucky, and Cincinnati, so he was quite familiar with the regional geography. He knew the location of the toll roads—manned by guards ready to sound an alarm about runaways—and how to avoid them. Simon Jr. knew just where farmland met streams or steep hills and where the bends in the road could obscure travelers. These gendered differences of mobility mattered because regional geographical familiarity—especially in the dark—proved essential to successfully navigate the family to freedom.4

Women were unlikely runaways for another reason: they rarely had the opportunity to disappear or absent themselves from work for any period of time without being missed immediately. On farms, the distinction of the work duties between those who worked in the house and those who worked in the fields was not as sharp as it was on large plantations. Enslaved women on farms did farmwork and housework. In addition to tending to crops and animals, these women cooked, cleaned, sewed, and nursed—or babysat—children for their owners. They worked virtually around the clock, meeting all sorts of demands and needs of members of the slave-owning family and their guests. And these women could hope for little reprieve from the on-call, around-the-clock work regimen, because their work and home spaces often were practically the same sites. Many owners of small farms could not afford to have separate structures for their enslaved workers, so they often lived in the main family structures, in the kitchens or other auxiliary rooms.5 Hence, living in such close quarters to whites, these women would be quickly missed if they escaped.

Most slaves who seriously contemplated running away understood that traveling with children posed huge challenges that exponentially decreased the odds of their success. The ages and number of children could make an already difficult journey even more conspicuous and trying. Infants, especially, had to be wrapped well to protect them from the extreme elements. The risks included frostbite, heat stroke, dehydration, exhaustion, and illness. Adults had to carry infants and small children whose legs could not handle the walking. Moreover, at any given point, infants and toddlers could, without warning, cry into the darkness, alerting sleeping owners or the slave patrol that someone was escaping. Understandably, few escaping with young babies or small children in tow were successful.6 Moreover, traveling with one child was difficult enough; more than two children made such journeys exercises in futility. Yet the Garners had four very young children, including an infant and a toddler. Given these odds, how did the Garners have the audacity to escape?

. . .

Enslaved people in Kentucky did not have as robust a history of plotting or executing slave rebellions as other slave states, although at least one completed revolt and a handful of significant plots occurred there.7 One possible explanation is that in Kentucky enslaved people were outnumbered by whites nearly four to one, scattered across the countryside, and often enslaved on farms with only one, two, or three others.8 On smaller farms and homesteads, enslaved people spent more time with whites, leaving little opportunity to gather as a community to air common grievances or to plot insurrection. In antebellum Kentucky, it was far more common for enslaved people to resist slavery through insolence, defiance, or covert forms of resistance like work slowdowns or feigning illness—in other words, individual acts not designed to overthrow the institution or permanently shed their slave status. Not content with those options, the Garners wanted a certain and final break from slavery altogether.

What were the probabilities of slaves securing freedom in Boone County, Kentucky—legitimately, or otherwise? Geography created the best biggest threat to the security of slavery in northern Kentucky. Boone County was close enough to Ohio, a free state, that slave owners faced the likely possibility of their slaves escaping at any point. Besides that, there were cross-state relationships that further increased the likelihood of escape. Many enslaved people in Boone County had free relatives living in Cincinnati who could facilitate their escape or hide them. Slaveholders with only a handful of slaves could not afford to lose any to escape, making them more controlling and watchful over the movements of their bondspeople. Consequently, enslaved people in that area found that freedom was hard to come by—either through escape or manumission. In 1850, twelve Boone County slaves managed to escape slavery and another eight were manumitted—six of whom were freed by the same person.9 Taken together, only twenty African Americans—1 percent—obtained their freedom in that county that year. That is just a small snapshot of the dim dream of freedom in Boone County despite its proximity to a free state.

The Garners were undeterred by the odds. They had a clear vision of freedom and a mental roadmap of how to get there. Freedom was not an abstraction for them: a few of the Garner adults had been to Cincinnati and witnessed how free and freed African Americans lived. For example, Mary Garner said that when she was hired out in northern Kentucky, she had sometimes attended the Cincinnati AME church. Her experience in an independent black church—and an AME one at that—introduced her to a vibrant free black community that practiced a liberatory version of Christianity. Although she had been a Christian for two decades, there were no black churches in Richwood or Boone County, where they lived as slaves. Those experiences in the Cincinnati church undoubtedly affected her spirituality, view of bondage, and desire for freedom.10 Nor was freedom an ideal or remote fantasy for the Garners. Freedom was not a distant place outside of their grasp or awareness; freedom was sixteen miles away, and they knew the route.

A successful escape required careful planning, coordinated efforts, resources, advance knowledge of the geography and terrain, and the assistance of free blacks. The Garner escape was not impulsive; it was the result of at least a month of careful planning and coordination. Young Simon was the engine behind the entire scheme. Although they all collectively decided that they would escape, he made all the plans and supplied every resource they needed, including geographical knowledge, transportation, a pistol for protection, and a safe house.

The escape plan hinged on making contact with black Cincinnati because the family needed people to assist them on the other side of the Ohio River. This support was critical: fugitive slaves with friends and kin in free states who were willing to provide assistance had better chances of success. In December 1855, Simon Jr. had accompanied Thomas W. Marshall, the nineteen-year-old son of his owner, to Cincinnati to drive hogs in for slaughter and sale, as he had done so many times before. The men had grown up at the same time and may have played together as children. Of the relationship, Thomas Marshall said that he had always treated young Simon as more of a companion than a slave. But by the time they were adults, few would have defined them as friends—largely because the racial and status boundaries between them had hardened, creating an unbridgeable gulf. For Simon Jr. this trip’s significance had nothing to do with work or male bonding; indeed, the trip proved to be a crucial factor in finalizing the Garners’ plans to escape. During that December trip, Thomas made the critical mistake of giving Simon Jr. some freedom to visit his wife’s relatives, Sarah and Joseph Kite. The Kites’ son, Elijah, was Peggy’s first cousin. Peggy, young Simon, and Elijah had spent some portion of their childhoods together in the same Richwood neighborhood before Elijah escaped in 1850.11

After taking leave of his young owner, Simon Jr. had inquired of several African Americans on the street where to find Joseph and Sarah Kite’s home. Most African Americans living in Cincinnati then knew who Joseph Kite was and where he lived. A man named Edward John Wilson directed young Simon to the Kite home on Sixth Street, east of Broadway, near the Bethel AME Church.12

Joseph Kite had been born into bondage on March 16, 1787, in Culpeper Court House, Virginia, where he spent the first sixteen years of his life. By the time he was thirty years old, his owner relocated to east Tennessee. Joseph eventually ended up in Boone County, Kentucky—likely owned by George Kite of Burlington, who had an enslaved workforce of seven. In Boone County, Joseph had met his wife, Sarah, who was nearly twenty years his junior. They had at least one child together, Elijah. Joseph hired his own time and earned enough money to eventually purchase his freedom in 1825. He immediately moved to Cincinnati, joining a heavy stream of African Americans who shed their slave status, legally or otherwise, and settled in Cincinnati, “Queen City of the West,” in the 1820s. Joseph Kite bore the distinction of being among only a small number of African Americans who lived in the city before the great exodus of 1829, when impending mob violence precipitated the historic exodus of half of the black population. Here, at least, jobs abounded to nearly the same extent as the racism and legal proscriptions black settlers faced. Joseph Kite worked as a peddler for many years.13 Although not considered entirely respectable work, the entrepreneurial nature of peddling worked in his favor; he soon had saved enough to purchase his wife and contracted with Wilson Harper, his son Elijah’s owner, to purchase him for $450. Elijah escaped in 1850 with his wife and their five-year-old child before the transaction was complete, though. Now a fugitive slave, Elijah settled in central Ohio for a few years and then moved to Cincinnati to be nearer to his parents. When Harper learned of Elijah’s whereabouts, he chose not to retrieve him under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, but decided, instead, to take a gamble and sue Joseph Kite for breach of contract regarding the broken purchase agreement. Joseph Kite hired abolitionist attorney John Jolliffe to defend him, who persuasively argued that the contract was nullified because it had been drawn up in Ohio, where laws prohibited any buying and selling of slaves.14

A thirty-year resident of one of the most racist cities in antebellum America, Joseph Kite had witnessed more than his fair share of mobs and near mobs. However, he also had witnessed much good in Cincinnati, including the establishment of several of the city’s first black churches and schools, as well as the growth and stabilization of the black community. He was a pillar of that community. Kite had lived in the city long enough to see the Underground Railroad grow from a few committed free blacks who risked life and limb, to a strong interracial network stretching across several Ohio counties. Joseph and his son, Elijah, knew the inner workings of the Cincinnati Underground Railroad and who the main conductors were. Even if they were not operatives in that movement, they became de facto activists when their own kin made the decision to seek their assistance. Simon Jr. reasoned that the location of the elder Kites’ home—in a very populated section of town in the heart of the black community—was too conspicuous. Besides that, everyone knew Joseph. Elijah, however, lived in a less dense part of town in the western section of the city. Simon Jr. weighed the likelihood of capture at both homes and decided he would take his family to Elijah Kite’s residence once they crossed the Ohio River.

During his Christmas visit with Peggy’s relatives, young Simon had familiarized himself with the exact location of the home at Sixth and Mill Streets. He remained with the Kites for two days and even enjoyed a Christmas play before meeting up with Thomas Marshall to make the journey back to Richwood. That visit ensured him that they had a destination and capable support on the other side of the river and allowed him to finalize the family’s plans to flee.

Young Simon might have claimed his own freedom then, based on his stay in Ohio. State laws protected black freedom for those legally on its soil. According to the 1841 State v. Farr ruling, an enslaved person brought into Ohio willingly by his or her owner, even with the intention of simply passing through it, was considered free.15 He could have taken advantage of Thomas’s mistake of bringing him into the state and boldly claimed his freedom in a court of law and won. Joseph Kite’s abolitionist attorney, John Jolliffe, would have made certain of that. Moreover, had young Simon absconded then, he could have easily put himself into the capable hands of Underground Railroad agents—never to return to bondage or Boone County. Instead, he made the selfless, but ill-fated, decision not to pursue freedom without his family, so he returned to Kentucky with Thomas Marshall.16

The Garners waited nearly three weeks to escape after Simon Jr.’s return to Richwood. Perhaps they did not have an earlier opportunity. When the opportunity did present itself, the family coordinated the departure of Peggy and her children, Tommy, Sammy, Mary, and Cilla, who lived on the Gaines farm, named Maplewood, and Simon Jr. and his parents, Mary and Simon, who lived on James Marshall’s property. Timing was critical: they had to wait until all their owners had retired to bed on the night they planned to leave. They also had to be careful not to leave too early, lest they awaken the sleeping families with the slightest sound; yet they also had to leave enough time to travel the sixteen miles to Cincinnati, which was a day’s journey by foot under normal circumstances. The Garners knew there was no way they could have made the long journey by foot—especially with four small children and with Peggy being pregnant. Moreover, the sixteen miles between their farms in Boone County, Kentucky, and freedom in Cincinnati, Ohio, would seem like a thousand in freezing temperatures. So Simon Jr. found transportation for the family of eight: a sleigh and two old horses from the Marshall farm to pull it. He and his parents brought the horse-drawn sleigh over to Maplewood to collect Peggy and the children at 10:00 p.m. on 27 January 1856.17

The night of 27 January was exceptionally frigid—cold enough that the Ohio River was frozen. Conventional wisdom would lead one to question why the Garners left in the winter with its frigid temperatures and snowy, icy conditions; but the warmer months actually posed more obstacles to travel and risks of discovery. First, more people would have been outside in the evening in the warmer months, ensuring that someone would have seen the fugitive family along the way. Second, there would have been no way to convey a party that size and with such small children in warmer weather; they would have had to walk. The sleigh across snow made travel infinitely easier and faster than walking. Finally, in warmer months, the Ohio River, which separated the slave south from the free north, would have been a barrier to freedom, because they would have needed a boat or skiff to get across. It would have been exceedingly difficult to find someone willing to ferry them across because Kentucky laws forbade ferryman from carrying African Americans across the river without a permit from their owners.18 Moreover, the fugitives would have needed a boat big enough for eight—an unlikely prospect.

One advantage of having worked in such proximity to the river for all those years is that the Simon Jr. knew its particularities. For example, in the nineteenth century, those who knew anything about the Ohio River knew it frequently froze solid in January and February; and when it did, it became a natural bridge from the slave state of Kentucky to the free state of Ohio. This knowledge was invaluable to the fugitives and dictated when they escaped. In sum, it actually was wiser and easier to flee in the winter.

The journey took the family all night. The fugitives likely would have stayed off of the main tolls roads lest they be discovered by toll guards. Instead, they likely would have taken farm roads and open fields to avoid the guards, who would have sounded the alarm. We can only speculate about what delayed them, but a couple of old horses pulling an entire family of eight through snow would have been a hard tow. The long journey pushed the horses to their limits—the animals barely finishing the task of towing the weight of eight people the sixteen miles to the riverbank in frigid temperatures. The Garners abandoned the horses and sleigh at Washington House, a Covington hotel, and walked the last few hundred feet to the edge of the frozen Ohio River close to the Walnut Street Ferry. There, they faced another obstacle: crossing the half-mile-wide river undetected. Police watchmen were supposed to keep close watch of the river to ensure that fugitive slaves did not cross. Young Simon had lived in northern Kentucky, so he would have been familiar with the location of the watchmen’s posts.

After getting past night watchmen, the Garners’ next obstacle was moving across the ice, an unnatural walking surface, especially in the dark. Each of the adults would have carried a child across the river, since all but one was too small to navigate the ice without slipping and falling: Tommy, the oldest child, may have walked on his own. Each step the Garners took would have collectively put thousands of pounds of pressure onto the icy surface. Any misstep on a fragile section of the ice could have cracked it, sending some or all of the Garners to an icy death. The drama of an enslaved mother crossing the frozen Ohio River with her child in her arms was not a new one. The character Eliza in Uncle Tom’s Cabin is based on the real woman, Eliza Harris, who also escaped slavery and ran across the frozen river years before Peggy Garner.19 In fact, we will probably never know how many other enslaved mothers made the same perilous decision to cross the icy river on foot.

As they crossed the frozen Ohio River, the Garners shed their slave status and put on the mantle of freedom. The younger couple decided to assume new names, which served the triple functions of hiding their real identities, distancing themselves from their enslaved pasts, and claiming new destinies on free soil. And apparently, it was fairly common for fugitive slaves to choose new names in freedom. Peggy assumed her formal name Margaret (Peggy is the common nickname for Margaret); like his wife, Simon Jr. may have adopted a formal birth name or even a middle name when he chose to be called Robert. The couple’s four children and young Simon’s parents retained their names. Peggy and Simon Jr. would walk into the annals of history bearing their freedom names of Margaret and Robert.20

The Garners made it to the Cincinnati riverbank after sunrise on 28 January—hours later than they had hoped. Unfortunately, sunrise increased the risks of someone seeing them. Still, they pressed onward. Robert led his family to a house at Sixth and Mill Streets in the western part of the city, four houses from the Mill Creek Bridge. Their journey finally ended at around 8:00 a.m., some grueling ten hours after it had begun, at the home of Margaret’s cousin, Elijah Kite, and his wife, Mary.21

When they arrived, the Garners were tired, hungry, and cold. Kite welcomed his cousin and her family and introduced them to his wife, who began preparing their breakfast. The family decided it best to move to a more secure location immediately after breakfast. To that end, Kite hastily left to consult with Levi Coffin, a Quaker Underground Railroad operative, about how to move the large family to a safer location. As a white man, Coffin not only had more experience with large parties of fugitive slaves but also enjoyed civil rights that would safeguard against anyone barging into his home, searching it without a warrant, or seizing any occupants. As an African American, Kite did not enjoy these rights. Besides that, by harboring his cousin and her family, he risked a $1,000 fine and a six-month imprisonment under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. In a city like Cincinnati, which had a long history of antiabolitionist violence, Kite also risked being targeted by a mob. Coffin advised him to move the family further up Mill Creek to a black settlement that routinely harbored fugitives.22 After leaving Coffin’s house, Kite hurried back to his own home intending to follow his advice. Unfortunately, shortly after he returned home, he got some unexpected visitors.

Archibald K. Gaines, the owner of Margaret and the children, had discovered the family was missing only a few hours after they left Richwood and had gone after them with dogged determination. Before getting on the road to Cincinnati, he had gone over to the Marshall farm to see if the rest of the Garner family had escaped. There, the slave-owning neighbors learned that the entire family indeed had left, taking a sleigh and two horses with them. Marshall, who was too ill to travel, sent his son Thomas to retrieve his slaves.

Gaines and young Marshall quickly closed the distance between themselves and the fugitive family. It was not hard to follow the clues the Garners had left along the way, including the sleigh and horses left abandoned in Covington. Gaines and Marshall knew that the Garners’ kin, Joseph and Sarah Kite, resided somewhere in Cincinnati. Moreover, Thomas Marshall would have remembered that Robert had gone to visit them late the previous year. After some inquiries, someone directed the pursuers to Elijah Kite’s street. There, a girl pointed out the home and informed them that the party had gone inside.23

Once they knew the family’s location, the slaveholders left someone to watch the home while they went to secure a warrant under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act from John L. Pendery, the United States Commissioner for the Southern District of Ohio. The provisions of that law granted slaveholders authority to retrieve runaways in free states. It also provided for the appointment of federal commissioners, or officers, in local communities throughout the nation who were charged with enforcing the law. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act outlined a clear process for owners to reclaim fugitive slaves: Upon discovering the whereabouts of their slave, owners had to go before a commissioner who could issue a warrant for the alleged fugitive’s arrest. The federal commissioner would then deputize citizens, bystanders, and posses to help execute the warrants. The law stated that “all good citizens [were] hereby commanded to assist in the prompt and efficient execution of this law.”24 Once in custody, the accused runaway would be brought back to the commissioner for a hearing. The burden of proof for the owner was very low: the only requirement for a person to establish ownership was a witness or affidavit from someone in the home state attesting to the fugitive’s identity. In this case, Gaines and Marshall would serve as each other’s witness. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act outlined harsh penalties for those who interfered with, or failed to enforce the law, with federal criminal charges, a fine up to $1,000, or civil lawsuits for the value of the slave. Moreover, the law provided commissioners with a decent incentive to rule in favor of the claimant: commissioners who remanded an African American to slavery were paid $10 and those who ruled in favor of the alleged fugitive received only $5. In current terms, that is equivalent to $247 versus $123. Some interpreted the unequal rewards as an attempt to bribe commissioners. Abolitionists and African Americans believed the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act to be wholly corrupt and designed to benefit slaveholders.25 That was the grim reality of what the Garners would face should they be recaptured. In sum, they did not stand a chance under this legislation.

After Gaines and Marshall appeared before Commissioner Pendery the morning of 28 January, he promptly issued warrants for the Garners, giving them to John Ellis, the federal marshal, to execute. Pursuant to the provisions of the legislation, Ellis deputized a posse of white men from Cincinnati and northern Kentucky to help execute the warrants. Then the newly deputized marshals, Gaines, and Marshall quickly returned to the Kite home by 10:00 a.m. with warrants in hand, to recover the family. Elijah Kite barely had beaten them back to his home. Apparently, Robert Garner was none too happy that Elijah had not made arrangements to get the family out of the city ahead of time as they had planned. That fact, plus Elijah’s delay at Coffin’s house the morning of their arrival, and his return to the home only moments before the marshals arrived led Robert to suspect that he had betrayed the family. It remained a sore spot for Robert until his death.26 In reality, though, there is no evidence that Elijah had betrayed his cousin and her family to their owners; he may simply have been an ineffective Underground Railroad operative. His missteps, though, canceled the family’s herculean efforts to escape slavery.

The Garners were finishing breakfast when the marshals pounded on the locked doors and windows with the authority of the federal government on their side, demanding that they surrender. Mary Kite, Elijah’s wife, refused the party entry; Elijah first agreed to let the authorities in but changed his mind.27 Outside, a crowd—composed of curious passersby, neighbors, proslavery and antislavery sympathizers, deputies, members of the press, and African Americans—gathered around the home and grew larger by the minute.

The deputies tried to force their way into the home. Cornered, the family scrambled, not sure what to do. Robert pulled out a pistol he had taken from his owner to protect his family’s freedom. The men had decided to “fight and die” rather than return to slavery. Surely, Robert had freedom and death on his mind as he fired at a deputy who tried to come through a window of the cabin. The bullet hit the deputy, shattering his teeth and leaving his finger hanging “by a mere thread.”28

The Garner men’s decision to resort to armed defense is remarkable for a few reasons. It was a powerful assertion of manhood neither ever had been able to assert in Kentucky: the power to protect their family from everything that had hurt them in the past, plus all that threatened to hurt them outside the doors of that Cincinnati home. Hence, they enacted a type of heroic power that was largely elusive for enslaved men. Moreover, it was a brazen act for African Americans to fire at white men—especially deputized federal authorities—who outnumbered them and had greater firepower. Their decision to use deadly force to avoid capture was not without precedent, though. Other fugitive slaves had used deadly force to avoid capture before the Garners, including in Christiana, Pennsylvania, in 1851. Then, when Maryland slave owner Edward Gorsuch tried to reclaim his slaves from the home of free black William Parker, the armed inhabitants inside shot and killed him and gravely injured his sons.

There were consequences for shooting at white men in the Ohio Valley. Had the shooting occurred across the river in Kentucky, laws there decreed that an enslaved person convicted of maliciously shooting a free white person with the intent to kill could be punished by death, whipping, or imprisonment; a conviction for murdering a white person carried the death penalty.29 In Ohio, a free state, there were no specific laws against fugitives shooting, injuring, or killing white men, but black on white violence certainly would lead to an extralegal death sentence. African Americans’ armed resistance against whites in Cincinnati always prompted swift mob violence against the entire community. None of the consequences deterred Robert from firing a gun against white deputies.

Initially, Margaret, Mary, and the children were in the front room of the Kite home with the Garner men. As Margaret watched the unfolding struggle at the door and became convinced of the inevitability of the family’s capture, she grew increasingly agitated, if not panic-stricken, after Robert shot the deputy. She decided to use deadly violence, as well. Grabbing a butcher knife from a counter, she rushed toward her children, grabbing two-year-old Mary and declaring, “Before my children shall be taken back to Kentucky I will kill every one of them!” While the men were trying to keep the posse from gaining entrance, Margaret snatched up two-year-old Mary and quickly cut her throat, right to left. She practically decapitated her daughter with a cut that was estimated to be four or five inches long and three inches deep. She threw the bleeding, dying child to the floor in the corner of the room. Margaret roared to her mother-in-law, “Mother, help me to kill them!” The older woman—the only adult witness to the impending horror—returned, “I cannot help you kill them!” Mary Garner did nothing to stop Margaret from harming her grandchildren; instead, she turned, ran from the room, and hid under a bed in an adjoining room. Not content with taking just one child’s life, Margaret then grabbed her sons one at a time and tried cutting their throats. They both fought back, though: one begged for his life, crying, “Oh Mother, do not kill me!” Hearing the commotion and screaming from the boys, Mary and Elijah Kite ran into the front room and witnessed Margaret trying to kill them. Mary Kite rushed over to Margaret and struggled with her for the knife. Tommy and Sammy took that opportunity to run into the next room and hide from their mother under the bed with their grandmother. Once Mary Kite wrested the knife from Margaret, she sternly told her not to kill her children—apparently still unaware that a child already lay bleeding with its neck cut open just a few feet away. Margaret went after the knife a few more times until Mary Kite gave it to her son to put in the privy behind the house.30

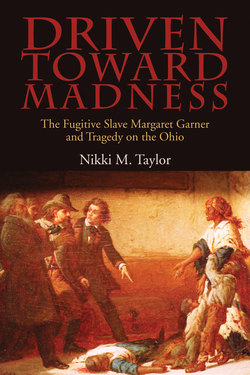

Figure 1.1. Pencil drawing of the Thomas Satterwhite Noble painting The Modern Medea (1867). Granger, NYC

When the Garner men—who had been occupied preventing the deputies from entering the home—turned and saw what Margaret had done to little Mary, Robert started “screaming, as if bereft of reason,” and pacing the room. His anguish was palpable—a testament to how much he loved the little girl. Old Simon groaned, while pacing too, and his wife wept inconsolably. Sheer pandemonium reigned inside the cabin. The men paced and wailed; the boys trembled under a bed—terrified of their own mother; the Garner matriarch cried; and deputies battered in the door, successfully gaining entrance. Meanwhile, as everyone else was focused on the specter of the dying toddler, Margaret, with laser-focused attention, decided to finish her mission. As the marshals battered their way into the now unmanned front door of the home, Gaines instructed the deputies not to do anything illegal. His last directive was that “no harm whatever should be done to the little children.” As they burst into the cabin, Robert fired his pistol a few more times at the entering party, but hit no one. Gaines, following behind a marshal, rushed in, grabbed Robert by the wrists, and wrested the pistol away before he could fire another round. Before Margaret could be apprehended, though, she picked up a heavy coal shovel, aiming it at her youngest child, Cilla, who was on the floor in the front room. She managed to bash her daughter in her face with the shovel one time before deputies grabbed it from her. The younger couple reportedly fought the deputies with “the ferocity of tigers” to avoid being taken.31

It is important to state here that trauma is not fully digested or comprehended until later. There is a period of latency, and then the trauma of that violence may rush back at once in ways that shock or debilitate the trauma victim. The act of leaving the site of trauma—what Sigmund Freud calls “a form of freedom”—is what accelerates the recognition of the trauma and, ultimately, fosters its eruption. In other words, Margaret’s facing recapture and the possibility of returning to her Kentucky enslavement may have led to a rush of traumatic memories and an eruption that resulted in murder.32 Hence, her trauma—consisting of interior and exterior injuries—is central to understanding what had driven Garner to escape bondage and, when that failed, to commit an infanticidal act.

The family had generational responses to the threat of recapture. The older couple had a quieter, less confrontational response: elder Simon did not use a weapon, and his wife hid under a bed. The younger couple, by contrast, used armed violence to resist returning to the lives they had left. Margaret and Robert each brandished weapons—he a pistol, and she a knife and shovel; neither hesitated even the slightest to use them. The couple gravely injured people in the process of resisting: Robert shot a deputy, while Margaret slit one child from ear to ear, bashed another in the head with a coal shovel, and tried to cut the throats of her other children. The difference in the violence committed by husband and wife is that he turned his weapon outward toward strangers who threatened his family, while Margaret turned hers inward to her own children.

Aggression, public violence, and armed self-defense were understood to be prerogatives of white men in the nineteenth century. Through their violent resistance, the younger Garners exercised a form of power that was a right reserved to white men. The irony is, of course, that as a legally powerless, enslaved woman in a racist and patriarchal society, Margaret had been an object and target of violence her whole life; as a free woman striving to assert her freedom, she became an instrument of deadly violence against someone who was even more powerless than she—an enslaved, female child.33

With Margaret and the men restrained, the deputies rushed from room to room trying to reclaim the other fugitives. They found the elder Mary Garner hiding under a bed with Tommy and Sammy. When deputies pulled them out, they noticed that Tommy bled from two cuts on his throat—one four inches long—and Sammy from gashes on his head—injuries inflicted by their mother. Cilla’s head was swollen and bruised. She bled from her nose as the officials removed her from the Kite home. Someone in the home tenderly wrapped little Mary in a quilt and put her on the bed in the next room. Though cut from ear to ear reportedly, the toddler did not die swiftly. According to witnesses, she gasped and struggled for air as a male neighbor carried her from the bed into the outside yard. She was dying as her parents, grandparents, and siblings were being apprehended, led outside, and loaded into an omnibus, a horse-drawn bus designed to transport groups of passengers in the mid-nineteenth century. As the omnibus carrying her entire family left the scene, little Mary Garner was in the arms of a stranger as she took her last breath.34 So ended the Garners’ quest for freedom. Sadly, their brief freedom in Cincinnati had been marked with violence, much like their bondage.

Still in front of the Kites’ home after the omnibus departed, Archibald K. Gaines took Mary’s body from the arms of the neighbor, intending to take it back to Covington for a proper burial in a slave cemetery. The crowd vociferously objected to his removing her body before a proper coroner’s inquest could be made into her death. Gaines complied and awaited the arrival of Hamilton County Coroner John Menzies, who had been summoned to the home. Coroner Menzies was himself from the same Richwood neighborhood as Gaines and knew the family quite well.35 He immediately examined the scene and the girl’s body, while Gaines patiently waited for him to finish—apparently more concerned about securing Mary’s body than securing his other slaves. When Menzies completed his examinations, he gave the toddler’s little body back to Gaines, who loaded it, and then proceeded to the Hammond Street jail. A neighbor claimed he held a funeral, but it is not clear where Gaines laid the toddler to rest.36