Читать книгу Wirehaired Pointing Griffon - Nikki Moustaki - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

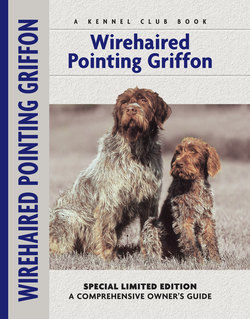

ОглавлениеThe word “griffon,” as a generic term, refers to a shaggy, rough-coated dog with a downy undercoat. Dogs of the griffon type have been known in Europe since the mid-1500s, hundreds of years before the advent of the versatile gundog that is the subject of this book. A French word, “griffon” appears in the names of a few American Kennel Club breeds, such as the Brussels Griffon, Petit Basset Griffon Vendéen and, of course, the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon. The Wirehaired Pointing Griffon (WPG) for generations has inspired an unrivaled passion and devotion from its followers. A superb gundog, a loyal house dog and a gentle friend to the children of the family, the WPG is still little known to the dog layperson but has long been a versatile treasure to hunters all over the globe.

Few dogs can compare to the WPG in terms of hunting skills, devotion to his owners and a gentle demeanor with all family members, including the children.

Though the French lay claim to developing the “Griff,” the breed was actually started by a young Dutchman named Eduard K. Korthals (1851–1896). As the son of a wealthy banker and shipbuilder, Korthals had the time on his hands to develop a dog that suited his favorite pastime—hunting. His father bred cattle, so Korthals already understood something of selective breeding and genetics and sought to create an all-terrain, close-working, pointing and retrieving gundog that would be easy to care for and train. He was partial to the griffon, which occurred in many forms throughout Europe, and set out to find the perfect “type” (size, coat, temperament, etc.) in order to develop the ideal dog patterned in his mind. Since Korthals denied using anything other than griffons in his breeding lines, it’s difficult to ascertain which breeds or types of dog he incorporated into this new breed. Undoubtedly he used various spaniels and setters that were available to him in Holland and possibly the Barbet and Otterhound. Korthals actually did cross with a German Shorthaired Pointer but the results were disastrous, so he didn’t pursue it.

The Wirehaired Pointing Griffon, or the “Korthals Griffon,” as the WPG came to be known, began in earnest in 1874 when Korthals started his breeding program with a bitch named Mouche, a brown-and-gray griffon who was reported to be a good hunter in a variety of landscapes. The other original dogs, or “Korthals Patriarchs,” were Janus, Satan, Banco, Hector and Junon. The bitch Trouvee, a result of a breeding between Mouche and Janus, resulted in the type of coat that Korthals was looking for, and a mating between Trouvee and Banco produced Moustache I, Lina and Querida. The lineage of all true WPGs can be traced to these dogs.

The Pudelpointer originated in Germany, where it was created in the late 1800s by Baron von Zedlitz by combining outstanding Pointers and Poodle-type dogs.

Two German Wirehaired Pointers, distinguishable by their eyebrows, mustaches and beards.

The German Longhaired Pointer is distinguishable by its wavy long coat and large size, standing up to 27.5 inches at the shoulder.

The Griffon Bleu de Gascogne, one of the many wirehaired hunting dogs of France, may well be in the make-up of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon.

CANIS LUPUS

“Grandma, what big teeth you have!” The gray wolf, a familiar figure in fairy tales and legends, has had its reputation tarnished and its population pummeled over the centuries. Yet it is the descendants of this much-feared creature to which we open our homes and hearts. Our beloved dog, Canis domesticus, derives directly from the gray wolf, a highly social canine that lives in elaborately structured packs. In the wild, the gray wolf can range from 60 to 175 pounds, standing between 25 and 40 inches in height.

Korthals, who was then working as an advance agent for the French Duke of Penthièvre, attended many field events, praising the merits of his dogs and informing the hunting community of Europe about the concept of his ideal hunting dog. In 1877 Korthals was offered the use of a large kennel in Germany, owned by Prince Albrecht of Solms-Braunfels. He moved his dogs to Germany and dedicated the next 20 years to the development of his Korthals Griffon. During this time, he worked with over 600 dogs, keeping only 60 that he considered correct for his new breed. He did extensive line-breeding (mating dogs of the same family to a common ancestor); thus in some pedigrees one foundation dog will occur many times, sometimes in dozens of places.

The breed became successful very early on, with Korthals competing the dogs in field trials and conformation shows. Though a fatal disease struck his kennel in 1882, killing 16 dogs, Korthals and his gundog friends all over Europe, particularly in France, were not daunted and continued developing the breed. Korthals died at 44 years of age on July 4, 1896, of laryngeal cancer.

A Griff stands proudly in the field with a fellow talented gundog of Continental origin, the Spinone Italiano.

Before Korthals’ untimely death, a split occurred among advocates of the breed. The Germans wanted a certain type of dog, and the French wanted another—both from the WPG. Once Korthals was gone, the rift opened even further. World War I, beginning in 1914, significantly hindered the breed’s progress in Germany, while French breeding took off and created what is essentially today a French dog with pan-European origins. Today the WPG exists mainly in France with about 14,000 dogs, while in Germany there are probably fewer than 600 breed members, about the same number in Italy and 200 to 300 dogs in each Holland and Belgium.

It is not known whether the French fell in love with the breed for its adept hunting ability or its personality. German hunting dogs, like the German Shorthaired Pointer, are like machines in the field, working consistently and tirelessly. The WPG is more of an artist, sensitive and a little moody, though he can also be consistent and driven. He can take a field trial by storm or not perform at all, depending on how he is feeling that day. The French say that the Griff will “invent” birds in the field—they go places where the other dogs haven’t thought to look. The WPG is also a much softer dog and far more laid-back. According to Philippe Roca, vice president of the American Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Association, a trainer should be as laid-back as the dog. “When you train, you need to be very creative and make training fun for the dog. Appeal to your dog’s intelligence. Channel his drive. You can’t tell him what to do. You use the Griff’s instinctual drive and channel it where you want. You can’t train the dog like you train a robot.”

The French school of training for the breed is also different. For the French, the WPG is a bird dog only. The Germans use the dog to hunt fur-bearing animals and to do blood-tracking as well, often with the handlers on horseback, which the French do not do. The two countries are still split on this issue.

A strong and skilled worker, the Griff is not all business—the breed’s charm and personality are evident in this lounging pack.

The first WPG registered with the American Kennel Club (AKC) in 1887 was Zoletta, a bitch who came to the United States and was recorded under the breed “Russian Setter (Griffon).” At that time, breeds with copious facial hair were supposed to have originated in the Siberian area, and so were registered incorrectly. In 1916, an official breed standard was established in the United States, and the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show boasted 16 competing WPGs. By 1929, the WPG was registered in the American Field Dog Stud Book and competed in hunting and pointing events. Unfortunately, the two world wars put a damper on the propagation of the WPG, and serious breeding ceased.

The WPG found its way back to the United States again after World War II, when a group of servicemen brought back the dogs they had seen and admired in France, Germany and Holland. The breed thrived, gaining loyal devotees in the many years following.

THE WPG FELLOWSHIP

The first WPG club was started by E. K. Korthals and his friends on July 29, 1888, and it was called the International Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Club. Specialty clubs in individual countries followed: the Royal Belgium Griffon Club began in 1895; the Club Français du Griffon d’Arrêt a Poil Dur Korthals commenced in 1901 in France; De Nederlandse Griffonclub initiated in 1911 in Holland; and the Griffon Club of America began in 1916, the year in which the official breed standard was instituted.

The Griffon Club of America fell apart under the pressure of World War II. But after the war, when the newly imported Griffs appeared in the States, Lt. Colonel Thomas Rogers and other breed devotees formed the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Club of America (WPGA) in 1951. The breed flourished for over 30 years, but a rift eventually overtook the breed again.

In the late 1970s and early ’80s, a faction of the WPG fancy was discontented with the quality of Griffs in the US and expressed the desire for better hunting dogs. The faction believed that there was too much random breeding that wasn’t well managed or well considered. The club started a committee to identify good breeding and began to hunt-test the litters of specific dogs. Those particular pups did not show well. The committee became frustrated at what they perceived to be the lack of “good” Griffs in North America. Someone outside the club suggested outcrossing the breed to German Wirehaired Pointers. Another advisor, a member of the breeding committee, suggested that the Griff would be best crossed with another hunting gundog, the Cesky Fousek (pronounced CHESkee FOWseck), a Czech breed which is similar in appearance to the WPG but whose hunting manner and disposition are more comparable to those of the German Wirehaired Pointer. This breed nearly died off during World War II even though the Czech government had been trying to resurrect it. Arrangements were made and the first Fouseks were brought over to the States. The outcrossed dogs were successful in competition, much to the delight of the group that supported this decision.

Even when relaxing, the WPG is keen, alert and ready to go.

The 2004 American Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Association specialty show was judged by Marian Mason Hodesson and won by Ch. Flatbrook Kyjo’s What a Sport, JH. A total of 42 WPGs competed.

However, another faction of the club refused to taint the bloodlines that Korthals had so carefully created. This steadfast group did not approve of the crossbreeding and held that these new dogs (often called Foufons by this group) were not true WPGs, though the WPG/Fousek group held that they were.

The split was definite. The pure-bred faction went off on its own to create the American Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Association (AWPGA). In 1991 the AWPGA was recognized by the AKC as the official parent club for the breed. The Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Club of America is currently not recognized by the American Kennel Club (AKC), United Kennel Club (UKC), Canadian Kennel Club (CKC), Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI), North American Versatile Hunting Dog Association (NAVHDA), American Field or the European Griffon and Fousek organizations. These organizations do not register or test the WPG/Fousek cross. Because of this, the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Club of America created its own registry, wrote its own standard and began holding its own field trial competitions.

Comparatively speaking, the WPG/Fousek cross is a more “square” dog, whereas the Griffon is more “rectangular,” longer than it is tall. Some of the dogs are also bigger. The mechanics of the dog has also changed. Its coat is a little tougher, as is its mentality, which is more like that of a German Wirehaired Pointer. These are not “bad” dogs—they are suited for the hunt and do well in field trials, but they are not pure-bred WPGs. The two groups are still philosophically divided, and heated discussions still occur. Nevertheless, members of both groups remain friendly, though neither will accept the other’s perspective on the matter.

Today there’s a healthy stock of WPGs in the United States. The WPG community is still very small, and most of the breeders know what the others are doing. When a litter is whelped, it’s not unusual for most of the community to know about it. Because the community is small, each breeder needs the others to keep the bloodlines strong and healthy. Dogs are still imported from Europe, primarily from France, and semen is also imported and used by breeders who want to improve their stock. Somewhere in the range of 400 to 500 Griff puppies are produced in the United States each year.

Best of Breed at Westminster in 2000, Ch. Jerome von Herrenhausen was shown by Cheryl Cates under judge Dr. Bernard E. McGivern, Jr.

Perhaps the most important goal of the 21st century for the American Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Association is to prevent another split, this time between those who show their dogs in conformation events and those who hunt. The AWPGA would like conformation dogs to also achieve top field results. As it stands, it’s often the case that the WPGs appearing at the weekend dog shows will be hunting in the field the following weekend, no matter what trophy or ribbon they bring home. The WPG, above everything, is a sporting/hunting breed which was bred for field work. The AWPGA’s emphasis is to continue breeding dogs that meet the breed standard and that can still hunt with the best of ’em.

The Griff thrives on doing his job and on his owner’s praise.

THE GRIFF ON THE HUNT

The Griff is indeed the consummate hunter, but it also competes successfully in agility events, obedience trials and tracking tests. Its proponents call it “the best-kept secret of the Sporting Group.” The breed’s versatility is what appeals to most of its fans. These dogs hunt successfully in all terrains and all weather, and they are competent swimmers. The breed was originally produced to hunt upland game birds, but it will also retrieve waterfowl and track and point on fur-bearing animals as well. It is known as an “all-game” dog.

Bill Marlow, president of the American Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Association, hunts his WPGs for pheasant and quail on the eastern shore of Maryland and hunts with the same dogs in canyons in Idaho on horseback. He has hunted ducks in Alaska and geese in Virginia with his dogs. “They swim and they have webbed feet and a dual coat like a Chesapeake Bay Retriever, and yet they’ll point and retrieve upland game at the same time,” said Marlow. “You can go duck hunting early in the morning, and when the ducks stop flying you can get up out of the blind and walk out into the field and go quail hunting, and the dog will find and point quail and will hold that point and retrieve the quail for you.”

The WPG has deep roots in the hunting dogs of Europe. As a result, the hunting instinct is very dominant in these dogs, without exception. Puppies will even begin pointing game at seven weeks old. Most people who own and breed these dogs will say, emphatically, that this dog is not a pet. This is not to say that the Griff isn’t a great companion because he is indeed a sensitive family dog, able to read moods and sprawl happily at his owners’ feet at the end of a day of rigorous hunting or running.

The Griff’s hunting style is more “European,” being a close-ranging hunter, bred to hunt with a human on foot, not on horseback. How far WPGs range depends on the type of cover and terrain, and they generally hunt in front of their human companion, though they will fall behind if the hunter passes a tightly sitting bird. Because they range close, voice commands and hand signals are ideal for WPGs.

Though they are known to be close-ranging hunters, some individuals have their own idea of how they should behave in the field. Bill Jensen, an AWPGA member and WPG breeder, once had a dog with an unusual hunting style. “I had one dog that was a ‘run-off,’” said Jensen. “He was absolutely self-driven. He wasn’t a team player. He was a French import and a wild, crazy dog—a very talented dog—but that one characteristic was frustrating. I never used him for breeding.”

With a wiry coat to protect him in the field, the WPG is well suited to working in many types of terrain.

The versatile Griff can be an excellent retriever in water and on land if properly trained.

Breeders are adamant that the WPG does not end up in “pet-only” homes. Not only does that situation eliminate dogs from the preciously guarded breeding pool in the US, it also prevents the dogs from doing what they were created for—hunting. The dog comes alive when he’s hunting. The moment the owner puts on his hunting vest, the dog knows that they are going out into the field.

There are a few Griffs each year that are destined for pet homes, usually those dogs that aren’t “acceptable” in terms of temperament and conformation. These dogs will be spayed or neutered and sold at a lesser price. It’s still important, however, that the dog be allowed to exercise himself by running as if on a hunt; according to WPG breeders and owners, jogging, walking or bicycling the dog around will not do. For the most part, even those dogs with minor conformational faults are still generally sold to hunting families and turn out to be remarkable hunters.

These are not city-dwelling dogs, though they are quite adaptable. They are more suited for country living where wide open spaces afford them the ability to dash around. The breed’s interest in the outdoors will not fade just because its owners do not hunt or hunt only occasionally.

Many hunters compete in AKC hunt tests where the WPGs excel over such dogs as the English Setter, German Shorthaired Pointer and Pointer. The WPGs are often the envy of the owners of other breeds. Marlow remembers fondly the first hunt test he went to with a WPG. “On the second day of the test I came up to the line and some of the fellows who didn’t know the dog with me said, ‘The guy’s got a Poodle! Look at that!’ The other guy turned to the first guy and said, ‘I saw this dog yesterday, and you’re going to wish you had one of those Poodles!’ Well, we started, and we didn’t get 20 feet before my dog was pointing a bird. There weren’t supposed to be any birds for another half mile, but she goes on point anyway, and I was really embarrassed. I pulled on her and said, ‘Let’s go,’ but the judge said I’d better step into the bush, and sure enough a bird took off! We were probably the fifth or sixth brace, so that meant that there were no less than ten dogs that had run right past that quail and never stopped.”

WPG DEVELOPMENTAL TIMELINE

| 1851 | Eduard Karel Korthals born—Amsterdam, The Netherlands |

| 1867 | Mouche whelped |

| 1870–71 | Franco-Prussian War |

| 1873 | Korthals begins serious breeding program |

| 1874–77 | Korthals acquires Mouche, Janus, Junon, Banco, Hector and Satan |

| 1875 | Banco whelped |

| 1877–79 | Korthals moves to Biebesheim am Rhein, Germany |

| 1879 | Donna acquired in Germany—longer coat |

| 1882 | Illness destroys 16 young dogs in Korthals’s kennel |

| 1885 | Vesta leased as a brood bitch. Good producer—rough coat |

| 1887 | Korthals and 16 other breeders sign and publish the breed standard |

| 1887 | Zoletta registered with AKC |

| 1888 | International Griffon Club formed |

| 1895 | Southern German Griffon Club in Bavaria formed |

| 1895 | Royal Belgium Griffon Club formed |

| 1896 | Korthals dies |

| 1901 | Club Français du Griffon d’Arrêt a Poil Dur Korthals formed in France |

| 1911 | De Nederlandse Griffonclub formed in The Netherlands |

| 1916 | The Griffon Club of America (GCA) formed and breed standard adopted |

| 1916 | Sixteen Griffons exhibited at Westminster Kennel Club |

| 1917 | New Country Life magazine article published, peaking interest in the breed |

| 1939–45 | World War II—serious breeding activity stopped due to war—GCA ceases to exist |

| 1951 | New club formed—Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Club of America (WPGCA) |

| 1980s | WPGCA splits into two groups; those wanting to crossbreed with Cesky Fousek and those who don’t |

| 1991 | American Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Association formed by those choosing not to crossbreed (AWPGA) |

| 1991 | AKC recognizes AWPGA as official national parent club for Griffons in the US |

*Chart courtesy of the American Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Association

Overall, the WPG is an energetic hunter and a charming companion, often surprising in his abilities. For the avid hunter, this breed is a blessing, an exceptional instrument and a winning cohort, achieving successes worthy of ample bragging rights.