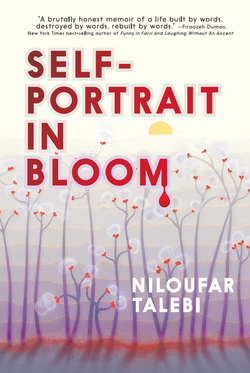

Читать книгу Self-Portrait in Bloom - Niloufar Talebi - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1. ME

I BEGAN WRITING THIS BOOK decades ago, and I have already rewritten it a thousand times over, erasing and recasting the past as I went and now go—a past ungraspable like the iridescence of an oil spill. Many selves of mine have come and gone and have yet to come. I have high expectations of my future selves. I want one of them to live with lions. Another to be a seducer of sculptors’ hands. Still another to backpack the wilderness alone. A discoverer of uncharted lands. An Egyptian actress in the Alexandria of Agatha Christie. Jeanne d’Arc. A grande dame, a doyenne with doting admirers seeing her through old age.

In a sense, I began writing my life as it was unfolding, or rather, seeing it through the lens of literature. When I was getting away with pranks in school, I thought I was a hero, funny. Later, as I recalled it, I marveled at the spirited girl who was leading. Now, I see that people don’t want to let others get away with being themselves because they themselves do not have the moxie to. I hung around my outsiders’ circle in college and wailed against “society” that owed us so much. Of our band of outraged, bohemian bosom buddies, one completely abdicated from society, as Susan Sontag put it, living without a phone in a hellish desert, another is a bar pianist in Paris playing for chanteuses, actualizing our “Lost Generation” idyll.

Time flows. New strata of me deposit onto the erased me. My life is alluvial.

This self-portrait, one slice of infinitely curated Creation Stories of me, is captured in print before its erasure. Therefore, it is fiction. But the Truth. A perfectly manicured chocolate cake that is not also a carrot cake or a cheesecake. Nor lemon meringue.

Let’s see if we can trace it all back to the mysterious origins of me, Tortured Artist.

I have no one to blame but myself.

For most of my life, I have felt unworthy.

I thought, or was made to feel, that I was bad. There was from me some expectation of domesticity, because I was born girl. I do not mean I come from the overt kind of patriarchal, honor-killing, Middle Eastern family you might be imagining right about now. No, our brand of patriarchy was more invisible. We are modernized, even Westernized. But herein lies the problem: Misogyny is embedded within Westernized societies that shrewdly deny their own kind of patriarchy, instead pointing fingers to the “barbaric” societies of the East they denigrate in order to colonize.

Being an artist, I betrayed the unspoken expectation of immigrant children—to restore the loss, repay the sacrifices made toward a better life for me in the new world. I think I have failed at this. The burden of this guilt exhausts me.

I backed out of so much. Children. Bourgeoisie. Casual friendships. Being generally “normal.” All in order to write. I bump against my marital life, which provides me with the sustenance necessary to write because I simply cannot swallow the framework that prescribes a specific role from me. (House)Wife.

Even as a full-blown adult, the act I show my father is largely a Theater of Good Wifery. It’s just easier not to debate when I am told I should be taking care of my husband, making him dinner. The taking-care-of-each-other advice goes both ways, but somehow it feels as if the bondage of domesticity is being passed down to me.

I have painted myself into one corner and one corner only.

So you see, I have no one to blame but myself. I was born girl. I became immigrant. I am artist. What the hell else did I expect?

They say that every new work of art redefines all those that came before it, offering a new reading of them, reorganizing them anew in the continuum of our collective imaginations.

Scientists say that each time we recall a memory, it loses fidelity.

Fidelity defined: The quality or state of being faithful; accuracy in details; the degree to which an electronic device (as a record player, radio, or television)—surely also the electric brain—accurately reproduces its effect (as sound or picture).

So we erase each time we remember. Each new recall, each new version then overrides and rewrites the past.

Erosion. Sedimentation. Ad infinitum.

Tehran, Iran, 1976 — Everything starts with this image burned into my memory: the back of a schoolgirl standing at her blue bedroom’s window watching snowfall. She writes four succinct lines in a notebook that is now lost. Somehow she knows this is poetry.

I saw all the whites in the sky, I saw them pile into bulging mounds on branches, I saw solitary flakes melt at the windowsill, I saw the throbbing silence of snowfall, I saw trees stripped to their elements, I saw their stillness and the stirrings beneath the frozen earth, I saw a hushed city, I saw the earnestness in my young parents’ tasks, I saw multitudes and beauty, I saw rivers stream down Mount Damavand, I saw another dimension, forces beyond the known, I saw the unspoken, I saw the mother, I saw the weight and the weightlessness of things, I saw time suspended, I saw the eternal.

| already solitary | |

| voyager | |

| whispers rose up in me | |

| when I was eight | |

| a feeling overcame | |

| from watching silent snowfall | |

| and | a poem was born |

| in my notebook | |

| covered in black plastic | |

| with diamond holograms | |

| four | |

| succinct lines | |

| simple | |

| perfect. | |

Silence is an animal with two faces:

| 1. | Voluntary silence Silence to breathe Silence into the labyrinth of the self Silence to cleanse Silence to undo and exorcise Silence, that buffer between bodies |

First born: London, England.

First birthday photo: dressed in a dirndl.

Perched at grandfather’s chest

mommy’s doll is stuffed

into white lacy tights that leave

their impression

on her Michelin Man legs.

Shuttled between Tehran and London

and Hamburg and Sunderland

the toddler is said to have

stopped crying

engrossed when placed in

front of the telly

with Tom Jones

singing and gyrating

his hips.

First momentous memory: possessed

jumping on a spare bed in the cool storage room

chanting, I have a peepee, I have a peepee.

The child’s make-believe world

in her blue bedroom

is a cozy bed encased

in a glossy, kelly green frame

an arcade of dreams

a pilgrim’s boat

its perimeter the frontier

separating shelter

and the vast ocean

of sharks and bogeymen beyond.

The all-night game: all limbs must stay strictly within the frame, or else

the beyond, the savage beyond.

Next door a little brother sleeps, his toy soldiers poised on battlefields.

Mommy dressed me at her closet of wonders and scents in a green polyester costume with flouncy sleeves she had sewn for my role as “leaf” in a kindergarten show. Or so I remembered for decades. Recently, a woman writes me saying she was my elementary school classmate. I try to find her name familiar, convincing myself that I do, as we do with so many fellow countrymen’s names that may or may not belong in our pasts. She mentions our “flower” play in elementary school.

Clank clank clank in Mommy’s heels down the hall when I am home alone…

Breathless from bliss on a tricycle.

Twirling my short pleated skirts

in front of the gramophone,

dancing with wrists bent, hands blooming magnolias.

Mommy makes snacks of steamed fava beans and red beets and turnips on dark winter afternoons.

A groovy, young father’s navy blue BMW 2002 with its bunny wabbit grill.

Velvet and wool blankets heaped over a low table we sat around, a heating unit housed under it, our legs jutting into the heated cubby, a toasty korsi on winter nights of soups and stews and writing between the lines.

Every school textbook opened with full-page headshots of the Shah and Empress Farah.

Sleeping in a girls dormitory for a summer where my bed is once covered end to end in sand, maybe from the beaches of the English Channel nearby, and my dolls are dismembered, and we hear rumors of a savage murder in the woods surrounding the international boarding school, but no one tells my parents back in Tehran and neither do I because I am somehow mute.

Barbie and Sindy dolls and their seasonal wardrobes and tiny plastic high-heeled shoes. Sindy’s lavender royal cape, purchased in Bath, United Kingdom. My love for shades of purple unmistakable even early on.

Riding a glittery gold bicycle on the grounds of the apartment complex around a large swimming pool downstairs from my blue bedroom.

An older, sensible father’s blue Peugeot 504 and its backseat booster seat. A turquoise and elongated ceramic figure, a mysterious seated feline, nestled on the shelves of my father’s office, a sprawling city where I run laps and get eye exams.

Dolphin diving in the pool in my red one-piece suit either holding my nose or wearing a pinkish, flesh-colored nose clip. Marco. Polo. Always with the fear of Jaws. Until dusk when we rush home shuddering, wrapped in our towels, lips blue and teeth chattering.

Too early, it was too early to cry each night into the pillow, too early to have begun fearing my parents’ abandonment of me. The death-fear that enters us at birth and propels us into our actions. Every church thrashing, every sports-arena roar, every holler of joy is to defy, delay the inescapable.

Reciting memorized poetry before the entire class as early as the first grade.

Multi-family trips to orchards in remote villages where one family or another owns land, zameen, in Karaj and other villages around Tehran. I begin to see the ruthless pecking order among children. Four, even two years apart was an unbridgeable valley then.

My generous surgeon father’s patients from near and far bear gifts of gratitude. Live turkeys we kept in our winter-emptied pool in the white house from the peasant patients, and Beluga caviar by the tin cans from the affluent.

A train ride to vacation at the Caspian Sea in the northern, subtropical region of Iran with the same families, physician colleagues of my father. It seemed as if we had taken over all the cars, a feast of parents standing, holding on to poles and children underfoot, weaving between pants and skirts, the anticipation of sun, sand, and beach in every cell of our bodies. Pickled garlic, mooseer, served with fresh fish only makes sense in that climate.

Lying on my stomach on the car’s backseat from a first-degree sunburn during the drive home through windy, mountainous roads connecting the Caspian Sea to Tehran.

Back home after the walks in the moist woods of the north, an itch at the base of my neck just inside my hairline. A tick fattens there—not of the Lyme variety. A doctor at my father’s clinic pops it off with pincers.

Hiking the mountains surrounding Tehran. My father so comfortable on those slopes. Stopping to breakfast on wooden structures built atop brawling streams flowing down the slopes. We sit at the wooden banquettes to have fried eggs, nimroo, tea, fresh-baked bread and farmer’s or feta cheese, and little bags of cheese puffs for the kids, inhaling that early morning mountain air. The breakfast everyone still tastes. There’s a feeling of freedom, endless possibility. We are in a film of entirely different people captured in silent and scratchy black-and-white celluloid. I was born with my father’s long legs. We are mountain goats, he and I, hiking the steep foothills of the Alborz mountain range north of Tehran, capped by the mighty Damavand peak.

Ever since the 1979 Iranian revolution was declared “victorious,” and one year of chaos had ensued as the Ayatollah Khomeini was digging his claws into government, schools had been gender-segregated, and hejab, women covering their heads and bodies, made mandatory. It was easy to hide one’s mouth discreetly holding the tail end of a scarf over it. I had just returned from the United States, where my father had sent my mother, brother, and me to take refuge while the bloody uprising was taking its course. I re-enrolled in the same school where I had spent my beloved elementary years, Ettefagh, the Jewish school across the street from Tehran University.

There, while in junior high, when a teacher was absent, as class monitor I corralled a classroom of sixty girls sitting by the threes in rows and columns of wooden benches like lines in an I Ching hexagram. We carved so many names into them. I took my stage at the blackboard and entertained with ad hoc performances of making faces, putting on voices, and any other shenanigan or skit that came to body. I could keep the class in stitches for the hour-long period. Which vice principal could object? No unruliness, no strays running down the hall.

Later, at another school, from my back-row bench I orchestrated a class of fifty high school girls. Their periodic mooing out of unmoving mouths drove the teacher to tears. Incapable of taking control of her classroom, she pulled me out of class, being that I was the straight-A class monitor, and implored that I find the ringleader.

I also mobilized the spitting of orange-peel pellets onto the blackboard. The tip of Bic pens that had been hollowed of their ink cartridges were punched into orange peel, pellets were lodged in and fired at the blackboard with a swift blow into the other end of the casing when the teacher was chalking the board.

On summer afternoons that stretched for eons, I retreated into Hemingway and Farrokhzad and de Chateaubriand and Gertrude Stein and Behrangi and Dickens and Emma Goldman and Al-Ahmad and Neruda and Fuentes and García Márquez and Daneshvar and Twain in my cool bedroom sanctuary. My father would, upon leaving home for the clinic in the morning, hand me a book—not picture books, we are talking Kafka—and tell me we were discussing it in the evening when he returned. And such went my literary education, and all the personas that I got to take on when immersed in those other worlds, intimate with so many characters and their dramas.

Nothing was missed from the absence of religious faith in my home. We had literature. My parents found spiritual solace in art. I would come to understand that the making of art promised that all my travails would be in the service of something better, building toward a redemption, giving my life an arc bent toward meaning.

During all the years I lived in Iran both before and after the revolution, I exchanged heaps of hand-written letters in English with pen pals all over the world. There were readily available forms I cannot remember how or through whom to be filled out and sent away that resulted magically in pen pal matches. I wonder whether children still practice this mysterious exchange, or whether internet connectivity hijacked this pleasure. Letters would arrive from faraway places in exotic or thin blue Par Avion envelopes bearing unfamiliar stamps and ink charting journeys through ports. I carefully lifted the stamps to add to my heavy stamp-collector’s book that was filled with picturesque stamps from my father’s correspondences from abroad and others he bought my brother and me at stamp stores, another favorite childhood token lost in emigration. I don’t have copies of the letters I wrote, nor any trace of where, to whom, and how many were sent. So many lost Creation Stories. Perhaps somewhere in my musty storage bags filled with letters received from my Iranian schoolmates after I left might be lodged an odd copy.

Packets of Pop Rocks arrived from America. The most memorable flavor: purple grape. I had never put anything like them in my mouth. Purely chemical tiny rocks unexpectedly thudding into the upper palate of my mouth. Almost violent.

What is time?

— A way of keeping track of how things evolve. The order of one thing coming after another.

— Causality. What causes what.

— A human construct, time may or may not exist.

— Everything may have already happened, and we are just aware of little pieces at a time.

— A way to ensure everything does not happen at once.

— Space is a way to ensure that not everything happens to us.

— A standard argument for time running forward:

We remember the past and not the future.

And what if we were going backwards in time?

We would progressively forget the past, undoing memories we have formed.

— We can time-travel into the past and the future:

We remember the first kiss and imagine next month’s vacation.

— People with dementia cannot imagine themselves fully or make new memories or predict the future. Our memories are crucial to our identities.

— Time feels longer if we are present. Time flies if we are busy.

I felt this during my car accident when all my attention went to that one thing, the swerving of my car across many lanes of the 405 freeway traffic toward the median at high speed while singing at the top of my lungs to Yma Sumac playing loudly on the stereo. My whole life did not flash before my eyes, but I did make a curious decision, or rather, the decision presented itself to me: I was moving to San Francisco—which I did on a Monday in December 1994, the day my physical therapy for broken bones ended. I had $60 in my pocket and no job, only a carry-on with a portable laptop and printer. When I was put onto a stretcher at the scene of the accident, I directed the paramedics to retrieve the master copy of a documentary I had made and was delivering to its producer from the glove box of the totaled car. I think of the accident as a not-so-gentle nudge to stop moping directionless at my parents’ home after college and to get my life going already.

Our experience of time distorted, we are visited by moments, tableaus. We attribute different degrees of importance to them by storing and dramatizing certain episodes, rendering them integral to our essence and being. Our sense of self is a game of Russian roulette.

While reaching back in time, I searched the internet for old images of my schools. Every time, I type the name of the school of my hearts, Ettefagh.

My mother was so exacting about my education that she would enroll me at the beginning of each school year in a name school that promised the moon: the American school, the French school among them. She would interrogate me every day after school to get to the bottom of how the day was structured, gauge if I had learned enough, and how much homework I had. Sure enough, no school ever passed muster, and two weeks into the school year, and a whole new school uniform to buy, I would return to Ettefagh, a public school with a reputation for high academic standards. In addition to being closed on Fridays, the Sabbath in Iran, Ettefagh school was also closed on Saturdays, following Jewish Sabbath, which was normally the first day of the week in Iran. I grew up with an unusual two-day weekend. To make up for the lost time, our school days were long, 8 a.m.–4 p.m. with a full load of academic classes. My arms were weighed down by a heavy leather bag of textbooks and notebooks, including ones with black nylon covers with a hologram design. I loved the time at the end of summer when we shopped for new school supplies. I loved choosing which notebook for which subject, writing my name in them with my favorite four-color pens in my well-practiced and eye-pleasing handwriting, keeping everything neat. At home I settled at my desk for several hours of homework each night. The endurance.

People just like me had posted their old photographs. Others had found vintage video clips, captioning them with nostalgic notes: Does anyone remember this? Our beloved school!

I looked hard into those black-and-white or faded images and shaky sepia clips for something. Anything—the window of my first grade class where I learned the letters A, B, and D in the first phrase we learn at school, Baba ahb dahd. Father water gave. The wide windows of the lunch hall where I would take my little first-grader brother’s hand after anxiously looking for him among the hundreds of uniformed, unleashed children running erratically like atoms under heat in the school yard, where we would haul our large, insulated, black lunch thermoses lovingly stacked with our mother’s homemade foods to eat together. My brother would not remember later that I cared for him like a worried mother.

I need pieces of the past to help me move forward. I pore over old photographs, images that enthrall me endlessly. I depend on them to live. They are frozen yet never stilted to my eyes. Private gazes into scenes summon shadows of memories, memories that are reverse engineered, manufactured from the photographs and mistaken, stored, and embedded as real memories. Each time I look at or think of them they animate whole fictions, myths that are more ancient and modern versions than the myths they conjure. While many fragments recede, some fragments magnify to become primitive symbols of my fears and drives. I redescribe their implications through my own experience. These myths are personal and sacred not because they are flights into an imagined antiquity, or remembrances of beauty, but because they express to me something real in myself, something ungraspable to me through other means, what fulfills a dim longing to belong to a greater sense.1

In these images, I looked for scale. Was that really the entrance that I went through every day? Where was the grand hallway through which my glamorous mother would strut like a movie star in her long fur coat to fetch me? Was it in reality a dingy corridor? Was she really wearing fur? Was what I imagined as the gilded gateway to Constantinople or some other rich, ancient city only a dilapidated and unused iron gate to the forlorn ramp next to the playground? Was that the temple with the high ceilings I would visit each morning before class, that endless field-maze of platforms and tables and podiums and Torahs we played hide-and-seek through? Where was that football field of a playground at the end of which the tastiest, greasy, chocolate donuts we called pirashki, and negrokees—chocolate-covered marshmallow treats—were sold from a low, gated portal in the wall? How far down the street was the stationery store with the puffy stickers, glitter, and designer erasers that smelled of fruits and bubble gum that I would sniff in sustained inhalations and even put in my mouth, they were so enticing.

We pronounced the name for the marshmallow treats as one word, negrokees, like necropolis, not realizing the Latin roots and racist reference of Negro kiss. The only black people I had seen were my African nanny and her husband. I only know this because I saw a photograph of them with my family on the occasion of their daughter’s birthday. I was a newborn. We were still in England. My petite young mother next to the large husband in native garb. I don’t know which country in Africa. In another photograph, my nanny, a nurse in the hospital where my father received his ophthalmology fellowship, is holding me on her lap, and my mother is standing behind her chair gazing at me in adoration with a craned neck. In Iran, I played with Jewish and Christian children in the same apartment complex, in the same school yards. I was exposed.

We peer so deeply into images of lost places and times for a hint of meaning as to who we were. We hope to superimpose our ghosts onto these spaces to make an imaginary film of our days, but the discrepancy between what we think was and what really was as we yearn to bridge in some way to what is lost, evaporated into another dimension of time, is our actual lives.

I once stood in a circle of other ten-year-olds, many of them well-toned Arab boys in tight designer jeans and shiny belts and crisp shirts and turbans, who took my fellow boarding-school mate, a blue-eyed, blond-haired Greek girl with honey skin who looked like our image of a Biblical angel, and passed her around and pummeled her inside the circle.

We were in a secluded part of the grounds near the woods. It was a misty summer by the southern sea of the English Channel. Five or six boys beating one girl. I remember freezing, staring dumbfounded. Before I knew it, the young-man-handling and assault was over.

Even early on I knew this was a Terror of Beauty—

which I later read about in Rilke’s Duino Elegies.

Beauty is only

the first touch of terror

we can still bear 2

The violence against me had not started then.

Not yet…

Decades earlier, in 1931, a boy of six, a future poet with the pen name Alef Bamdad, meaning A. Dawn or A. Daybreak, witnessed the bloody public lashing of a lowly soldier. A feeling overcame him, he said, and he knew.

He wrote:

I am Daybreak, in the end

weary

…

I was six the first time I laid eyes

upon grief-stricken Abel receiving

a whipping from himself

public ceremony

in full befitting swing:

there was a row of soldiers, a pageant of cold,

silent chess pawns,

the glory of a dancing colorful flag

trumpets blasting and the life-consuming

rapping of drums

so Abel would not ail from the sound

of his own sobbing. 3

When I was ten, around the disorienting time my body started to exist for me, I also became aware of my country. Iran was having a revolution, shedding its oppressive monarchy.

We left for the United States in 1978 and returned in 1979, a few months after the revolution was declared “victorious” with the Shah of Iran fleeing to Egypt, not knowing, as no one did, what we were returning to.

What unfolded over the following four and only other years I lived in Iran: chaotic arrests and disappearances, martial law, half of the brutal eight-year war with Iraq, violently enforced, compulsory hejab, the denouncement of alcohol, neckties, beardless faces, and anything “Western,” watching what you said in public—anyone could be a spy, even the girl sitting next to you in class. Poor, angry, young men promised their comeuppance by the Ayatollah became the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, Pasdaran, armed with machine guns and beige Toyota Land Cruisers—seeing them still makes me double over with nausea—patrolling the streets with carte blanche to stop, arrest, confiscate, imprison, rape, kill. The birth of a religious dictatorship centuries in the making. And a mass exodus of which my family was a part.

And meeting Shamlou.

The poet, Ahmad Shamlou, also known as Alef Bamdad.

Iran underwent two pivotal events in the twentieth century regarding women and their dress.

The first was kashfe-hejab, the forced unveiling of women decreed by Reza Shah in 1935, the founder of the short-lived Pahlavi dynasty, a welcome decree by the Westernized upper classes, but traumatic for women whose covering was intimately connected with their religious devotion and identity, leaving them exposed, despondent. This fed the alienation between the clergy and the monarchy, causing clashes at various points throughout the century until the deposition of Reza Shah’s son, the Shah of Iran, in 1979.

The second was the forceful veiling of Iranian women imposed by the clergyman Ayatollah Khomeini’s new, brutal regime, usurped from the hands of the many factions that played a part in overthrowing the Pahlavi dynasty, “winning” the 1979 revolution.

The Ayatollah’s strong-arm men, the Pasdaran, were a motley band, sons of the underclass promised their rightful place in the revolutionary rhetoric. Their families had suffered in the margins of a society dominated by the British and the Americans, in turn priding itself for being modernized, Westernized, leaving behind tribal people, peasants, crafts people, denying them the upward mobility their exploitation provided the modernized and urban bourgeois class. These young men were recruited in the name of Allah, and with blanket power they exercised to take out their decades-long revenge upon the corrupt ruling class. And terrorize they did, breaking any and all rules, for it was the rule of chaos, unaware that they were mere pawns, strong-arms for yet another despotic regime that would soon forget them as well. Their violence included deflowering maidens upon arrest, justified by a self-serving interpretation of some likely falsified Koranic verse that no virgin could be killed. They were to be addressed as brother.

Once, I was dallying on the sidewalk with my mother and brother, waiting for my father to park and join us for our dentist visit, when they closed in, the brothers. Out of nowhere, cars including the domestic car, Paykan—not dissimilar to Soviet-era national cars—sped and screeched at our feet. Young men slinging machine guns leapt out.

The next thing I remember is all three of us on our knees. My ten-year-old brother’s silky prepubescent hair in a cascading bowl cut shimmered under the winter sun. The next snapshot is of my father, his gloves or wallet in both of his hands clasped in front of him as he usually carried things. What a scene to walk into. He argues with the brothers who would not be reasoned with, for they are not in the business of justice for the class that, as far as they are concerned, has thrived on the backs of their parents. Then, my brother, my father, and I are in the back seat of the Paykan, my father in the middle. The young man in charge is in the passenger seat addressing the windshield. My mother is standing outside probably with a gun pointing at her. Other guards are loitering around their own cars. The brother in charge has been to the front to fight in the Iran-Iraq war. My father, too, as a medical doctor serving for two months each year. The brother has had an injury that still looms. My father is able to give brother the medical advice he so needs. Brother lets us go with a warning.

Apparently a few wisps of my hair were hanging loose out of the new contraption in my life, my headscarf. This was Tehran in 1983.