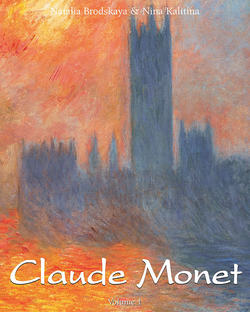

Читать книгу Claude Monet. Volume 1 - Nina Kalitina - Страница 4

Monet, the Man

ОглавлениеGustave Geffroy, the friend and biographer of Claude Monet, reproduced two portraits of the artist in his monograph. In the first, painted by an artist of no distinction, Monet is eighteen years of age. A dark-haired young man in a striped shirt, he is perched astride a chair with his arms folded across its back.

His pose suggests an impulsive and lively character; his face, framed by shoulder-length hair, shows both unease in the eyes and a strong will in the line of the mouth and the chin.

Geffroy begins the second part of his book with a photographic portrait of Monet at the age of eighty-two.

A stocky old man with a thick, white beard stands confidently, his feet set wide apart; calm and wise, Monet knows the value of things and believes only in the undying power of art. Not by chance has he chosen to pose with a palette in his hand in front of a panel from the Water Lilies series.

Numerous portraits of Monet have survived – self-portraits, the works of his friends (Manet and Renoir among others), photographs by Carjat and Nadar – all of them reproducing his features at various stages in his life.

Many literary descriptions of Monet’s physical appearance have come down to us as well, particularly after he had become well-known and much in demand by art critics and journalists. How then does Monet appear to us? Take a photograph from the 1870s. He is no longer a young man but a mature individual with a dense, black beard and moustache, only the top of his forehead hidden by closely-cut hair.

The expression of his brown eyes is decidedly lively, and his face as a whole exudes confidence and energy. This is Monet at the time of his uncompromising struggle for new aesthetic ideals. Now take his self-portrait in a beret dating from 1886, the year that Geffroy met him on the island of Belle-Île off the south coast of Brittany.

“At first glance”, Geffroy recalls, “I could have taken him for a sailor, because he was dressed in a jacket, boots, and hat very similar to the sort that they wear.”

“He would put them on as protection against the sea-breeze and the rain.” A few lines later Geffroy writes: “He was a sturdy man in a sweater and beret with a tangled beard and brilliant eyes which immediately pierced into me.” In 1919, when Monet was living almost as a recluse at Giverny, not far from Vernon-sur-Seine, he was visited by Fernand Léger, who saw him as “a shortish gentleman in a panama hat and elegant light-grey suit of English cut… He had a large, white beard, a pink face, little eyes that were bright and cheerful but with perhaps a slight hint of mistrust…”

Both the visual and the literary portraits of Monet depict him as an unstable, restless figure.

He was capable of producing an impression of boldness and audacity or he could seem, especially in the latter years of his life, confident and placid. But those who remarked on Monet’s serenity and restraint were guided only by his external appearance. Both the friends of his youth, Bazille, Renoir, Cézanne, Manet, and the visitors to Giverny who were close to him – first and foremost Gustave Geffroy, Octave Mirbeau, and Georges Clemenceau – were well aware of the attacks of tormenting dissatisfaction and nagging doubt to which he was prone.

His gradually mounting annoyance and discontent with himself would frequently find an outlet in acts of unbridled and elemental fury, when Monet would destroy dozens of canvasses, scraping off the paint, cutting them up into pieces, and sometimes even burning them.

The art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, to whom Monet was bound by contract, received a whole host of letters from him requesting that the date for a showing of paintings be deferred. Monet would write that he had “not only scraped off, but simply torn up” the studies he had begun, that for his own satisfaction it was essential to make alterations, that the results he had achieved were “incommensurate with the amount of effort expended”, that he was in “a bad mood” and “no good for anything”.

Monet was capable of showing considerable civic courage, but was occasionally guilty of faint-heartedness and inconsistency. Thus in 1872 Monet, together with the painter Eugène Boudin, visited the idol of his youth, Gustave Courbet, in prison – an event perhaps not greatly significant in itself, but given the general hounding to which the Communard Courbet was subject at that time, an act both brave and noble.

With regard to the memory of Édouard Manet, Monet was the only member of the circle around the former leader of the Batignolles group to take action upon hearing, in 1889, from the American artist John Singer Sargent, that Manet’s masterpiece Olympia might be sold to the USA.

It was Monet who called upon the French public to collect the money to buy the painting for the Louvre. Again, at the time of the Dreyfus affair in the 1890s Monet sided with Dreyfus’ supporters and expressed his admiration for the courage of Emile Zola.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Claude Monet, 1872.

Oil on canvas, 61 × 50 cm. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris.

La Pointe de la Hève at Low Tide, 1865.

Oil on canvas, 90.2 × 150.5 cm.

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth (Texas).