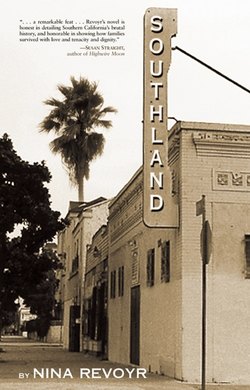

Читать книгу Southland - Nina Revoyr - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER SEVEN

1994

THERE WERE so many questions, which she took out in private, unfolded and examined like secret love letters. For one thing, why had no one in her family ever told her about the freezer? That no one talked about history, the internment, seemed a community decision; the entire Nisei generation might have taken a vow of silence. But this thing, the death of the boys, was much more personal, unique—and so her family’s silence on the matter was more troubling. She had known right away that she’d have to talk to Lois, who was always the best source of family information. Lois, like Rose, didn’t tend to offer things on her own, but at least she’d give them up when she was asked.

Jackie called her aunt on Tuesday night, as soon as she got home. They talked about the houses that Lois had looked at, and then discussed the will—the official one—which had been read that afternoon. Frank had left his computer and his savings— about a thousand dollars—to Lois, and to Rose he’d left some old books. Jackie, to her mild and bewildered disappointment, had been willed his box of documents and a bowling ball. As they both expected, there’d been no mention of the store.

After telling Lois that she was in no hurry to pick up her inheritance, Jackie took a deep breath. “Listen. I did some poking around about the kid in the will, Curtis Martindale.”

“Oh, really?”

“He worked in the store for a while.”

“Oh, right. Of course. That’s why the name sounded familiar.”

“Yeah. Well, he’s not going to be wanting that money any time soon. He’s dead.”

“Oh,” Lois said, deflated.

Why did she sound disappointed? Did she really have no clue? “He died in the Watts riots.”

Silence. Something rustled on the other end of the line.

“…in Grandpa’s store,” Jackie concluded.

Lois still didn’t speak. Jackie could hear her aunt breathing. Finally Lois said, “What are you talking about?”

Jackie stood and started walking, the phone cord twisting around her hips. “You knew about this, didn’t you?”

“Knew about what?”

Jackie’s mouth fell open. She repeated what Lanier had told her—about the store, about the freezer, about the suspicions concerning the policeman, Nick Lawson.

When she was finished, Lois was silent for a moment. Then she said, very slowly, “I had no idea. Mom made Rose and me leave the first day it was safe. The three of us stayed with Mom’s parents down in Gardena until Dad sold the house and the store.”

“Well, now you know why.”

“Jesus.” Lois remembered the frenzy of the days before the looting reached Crenshaw—how she and Rose weren’t allowed to wander the neighborhood, or even see their friends. The quick, messy packing of suitcases, the drive down to Gardena, where her mother’s parents lived. Lois crying about being plucked out of her house, her school, her life. Her father wild as she’d ever seen him, wide-eyed, in a frenzy. His whipped hair and bloodshot eyes when he came home from the store. How he slept in the garage and avoided the rest of the family, while her mother circled the rooms of the house, tight-lipped and victorious. I told you so, she kept saying to him. I told you this neighborhood was no good for our girls. “That cop sounds familiar, though,” Lois continued. “There was this awful cop in the area who used to harass Dad a lot. He’d come in and knock stuff off the shelves and take cigarettes and soda. He followed Rosie and me home a couple of times, really scared us bad. Anyway, as you can imagine, he was no big fan of black kids, either. I wonder what ever happened to him.”

“If it’s the same guy, he was shot in retaliation. He didn’t die, though, and he was never brought to trial or anything. Anyway, this Lanier wants to bring a case against him. We’re meeting again on Friday.”

“And you’re helping, like the good lawyer you are.”

Jackie noticed that she didn’t say “granddaughter.” “Well, it would be nice if they got him.”

“Yeah, I guess you’re right,” Lois replied. She remembered the ice-chill of fear as the cop walked behind her, humming low, lightly hitting his baton against his thigh.

Jackie put her fist on her hip and looked up at the ceiling, annoyed. “Well, you don’t exactly sound enthusiastic, Lois. Do you think I should forget the whole thing?”

“No, I’m just saying you should be careful.”

“Is there something you’re not telling me?”

“No. But it was an ugly time, Jackie. And if everyone knows that a certain person did this thing, but he was still never punished, then think about what you must be up against.”

“Right. But it’s almost thirty years later now. You’d think that someone would be brave enough to talk. I wonder if there’s anyone who actually saw Lawson in the store.”

“Well, unfortunately, it wouldn’t have been any of us. As soon as the looting started in Crenshaw, Dad locked up the store and came home. We all stayed there until it was over.” She remembered the four of them in front of the television, staying awake for days. Frank shaking his head and mumbling. Lois crying sometimes. Mary saying as soon as this is over, we’re leaving, Frank. Whether or not you come with us, the girls and I have to go.

“So Grandpa never left the house.”

“Not once the looters came, no.”

Jackie was relieved to hear this. She hadn’t thought he was involved in the murders, but it was good to know for sure. “But how did Lawson get into the store? Grandpa must have locked the door. Did anyone else have a key?”

Lois thought for a moment. “Yes. There were three boys who worked in the store—no, four. I think they worked at different times, so I don’t know who would have been there during the riots. Except, I guess, for Curtis Martindale.”

“Do you remember the other boys’ names?”

“Let me see now. David. And another D name…Derek. I don’t remember their last names, unfortunately. And a Sansei boy, Akira Matsumoto, who was a little bit older than Rosie. I remember him—he’d come back and visit even after he went off to college, and he had a really foul mouth. He was one of the original members of the Yellow Brotherhood.”

“The what?”

“The Yellow Brotherhood—they were kind of a gang. Not like the ones today. They formed for protection, mostly, and they had a political angle. I don’t think they lasted past the sixties.”

“Do you know what happened to the boys who worked in the store?”

“I don’t know what happened to the two black boys. Akira moved to Japan. He went to UCLA and got his act together, and then took a job in Tokyo. We’d hear about him sometimes because Dad stayed in touch with his parents. They might still be alive—I could look them up.”

“Right. But if you called every Matsumoto in the phone book, it’d probably take a year.” She paused. “Thanks for the help, Lois. Sorry to shock you with all this.”

“It’s not your fault. I’ll let you know if I remember anything else.”

Friday came, slow as Christmas or a birthday, and Jackie drove back down to Crenshaw. Lanier had given her the address for a place he called the “barbecue church,” and a little after two, she arrived there. In the corner of the parking lot was a huge, smoking grill, facing several picnic tables which were half-filled with people. Jackie parked her car and made sure all her doors were locked. Then she walked over to the tables.

She was nervous. There were about twenty-five people there, most of them young and all of them black. There were half a dozen older men, sitting together at a table. A middle-aged couple stood behind the grill, apron-clad, he marinating the big sides of beef, she twisting sausages with a pair of tongs. As Jackie approached, she felt self-conscious and not entirely safe. The teenagers looked at her and lifted single eyebrows in calm disdain. Jackie scanned the tables again—where was Lanier? But then he turned—he’d been sitting with his back to her—and waved her over.

“Thanks for meeting me here,” he said as she approached. “I needed to touch base with some folks at the church…” He gestured toward the building. “…and then I thought I’d get some lunch. I hope you haven’t eaten already.”

Jackie smiled. “I haven’t, actually. Once you told me there was barbecue involved, I figured I should wait.”

Lanier extricated himself from the picnic table, motioning for her to walk toward the grill. “It’s actually an interesting story. Twenty-five years ago, this was just an empty lot. Then the founders of the church started using it to sell barbecue ribs and hot links at lunchtime. Well, word got around and the food sold so well that the founders raised enough money to build the church.”

Jackie nodded, feeling encouraged. Lanier still hadn’t smiled at her, but he seemed much more relaxed than the first time they met. He wouldn’t have brought her here, she thought, if he disliked her.

They had reached the grill now, and Lanier gestured to the couple behind it. “This is Don and Mary Carter. Mary’s the daughter of the original church founders. And this,” he said to the Carters, “is Jackie Ishida, Frank Sakai’s granddaughter.”

At her grandfather’s name, both the Carters became animated. Mrs. Carter removed her hot-pad glove and held her hand out over the grill, her arm bisecting the waves of rising smoke. “It’s a pleasure to meet you,” she offered, shaking Jackie’s hand. “Frank Sakai’s a name I haven’t heard in a long time. He was a good man, your grandfather. Remember him well.” She paused. “I heard he passed on. I’m very sorry.”

Jackie thanked her, and they stood there awkwardly. Again, she had the sense that she didn’t deserve such sympathy. The luscious, meaty smells from the grill were making it hard to focus.

“Well, listen, honey, why don’t I fix you up a plate? I’d make one up for James there,” Mrs. Carter said, looking teasingly at Lanier, “but he’s already eaten ’bout a whole week’s supply.”

“Aw, come on, Mary. That was just one hot link to get me through my meeting. I’ll take a real lunch now.” He was smiling and his whole face changed. It was no longer a stern mask of angles and stark, immobile lines. He looked boyish and warm, more approachable.

Jackie could feel the eyes of the customers. The Carters’ reaction to her, instead of making the other people more comfortable with her, had somehow had the opposite effect. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d felt so scrutinized, exposed, and yet, there was a dismissive quality to the teenagers’ looks; she wasn’t important enough, even, to glare at. Mary Carter handed her a red and white cardboard box full of ribs, black-eyed peas, and corn bread. She waved off the ten Jackie offered and gave Lanier an identical serving. They each grabbed Cokes from the cooler. Then Lanier directed Jackie to the picnic table closest to the fence, away from the milling teens. He insisted that Jackie try her food, which she did—inhaling tangy mouthfuls of the tender pork ribs that tasted even better than they smelled. He started on his own ribs before wiping his mouth with a napkin and asking, “Did you find out anything interesting?”

“Maybe,” Jackie answered. She recounted what Lois had told her. How she and Rose hadn’t known of the murders. How Frank had reacted, shutting himself away, then moving the family down to Gardena. How three other boys besides Curtis might have had a key to the store.

Lanier stirred his Styrofoam cup full of black-eyed peas. “Any idea who they were?”

Jackie nodded. “Some. They were all teenagers, employees. Anyway, one of them was Akira Matsumoto, a Japanese-American, obviously, who ended up moving to Japan. The other two I only have first names for—Derek and David.”

Lanier tapped his fingers on the table. “David Scott. He was one of the other four boys in the freezer.”

“Oh. God. I don’t think my aunt knew that.”

“David and Curtis had just graduated from Dorsey. The other two, David’s little brother Tony and his best friend Gerald, would have been freshmen that fall.”

Jackie felt dizzy and grabbed the table. “Jesus.”

“Derek’s last name was Broadnax. I think he might have been there when the boys were found.” He paused. “His little sister Angela was Curtis’s girlfriend. I don’t remember what happened to them, but we could ask around a bit. Some of the old folks around here got memories like books. You think you could track down the Japanese guy?”

“Maybe,” Jackie said. “I’ll try.” She took a sip of her Coke and then, when she felt steady again, she tried the rich, moist corn bread. “Any luck on your end?”

Lanier sighed, waved to a man at another table, then looked back to Jackie again. “Some. I have a buddy who’s a detective at the Southwest Station. He grew up around here and he knew your grandpa, and he’s been doing some sniffing around.” He paused. Allen had not been willing at first. What James was asking was dangerous, too risky. The department was a sleeping monster that it was better not to disturb, and who knew what kind of creatures you’d find if you went digging in its belly. What secrets, half-digested, the twisted guts would offer up. Only after a few days had Allen changed his mind. He had loyalties deeper, he said, than the department. “Most of the cops from Lawson’s time have retired, you know, and the few who are still on the force have all moved up and out to desk jobs at other stations. It’s hard—no one’s gonna speak out against another cop.”

Jackie nodded, waiting.

“But Allen heard about this one guy, Robert Thomas. He and his partner worked at Southwest with Lawson, and they were the only two black cops there. Anyway, the partner’s gone, but Thomas is still around, up at the Hollywood Station.”

“Have you talked to him?”

Lanier took a bite of his ribs. A dollop of sauce got smeared on his cheek, and Jackie pointed at the same spot on her own face. Lanier wiped the sauce off with a napkin. “Tried to,” he said. “He thought I was a reporter. I called him at the station, and when I started to explain what I wanted, he interrupted and said he didn’t know what I was talking about. Then he hung up on me. I called back yesterday and tried to tell him I was calling at the suggestion of a cop—but he still seemed to think I was messing with him. But this time he remembered ‘the incident.’ That’s what he called it, ‘the incident.’ Said it was a terrible tragedy and he didn’t want to discuss it, why did the press insist on stirring up all those painful things from the past.”

Jackie took a gulp of her Coke. “What do you think’s going on with him?”

Lanier shrugged. “I don’t know. He probably does think I’m a reporter. And my guess is, he’s gonna retire in the next couple of years and he doesn’t want any kind of hassle. The last thing he’s going to want to do is dig up a scandal from thirty years ago.” Lanier paused, remembering the conversation. Thomas had been curt, self-protective, an old-school Negro. Lanier almost felt sorry for him—what twists, what back-flips he must have had to perform in order to succeed at his job. Thomas was his father’s age, and Lanier understood his suspicion, his fear. So many of the old folks had been crushed down and down.

“So what do we do now?” Jackie asked.

“I’ve got some ideas on that,” Lanier said, “but I’ll tell you about them later. Let’s get out of here before the traffic gets bad.”

They threw their trash away and waved goodbye to the Carters. They got into Lanier’s green Ford Taurus station wagon, strapped themselves in, and Lanier took a left onto Crenshaw.

“Where we going?” Jackie asked.

“We’re taking a drive.” They passed Crenshaw Motors, an old building with rounded corners that had clearly been there for decades. There was a string of small offices and stores on the right, and Jackie wondered how all these places remained in business—there didn’t seem to be enough foot traffic to support them. When she looked closely, she saw that many of the stores were empty. She thought of the ghost town she’d once seen, driving back from Arizona; she thought of the broken-windowed, barricaded buildings of Northridge, which she and Laura had toured the week after the earthquake. At the first big intersection, several blocks down, Lanier made a U-turn and they headed back north. Looking up, Jackie saw the Hollywood Hills in the distance, the tiny Hollywood sign, which was lovely, but incongruous, like someone had rolled in the wrong backdrop for a movie set.

“This area ain’t exactly hopping,” said Lanier. “But right up here, by Leimert Park, it’s nicer—this is what I wanted to show you. There’s a couple of art galleries, coffee shops, jazz clubs. And Magic’s new theaters are helping bring people to the mall. You should see this place on Sunday, when they shut Crenshaw down to traffic and the kids all come.”

He walked over sometimes, just to watch the show. The young brothers in their souped-up cars, shiny old Pontiacs and Buicks that rattled and groaned like prehistoric beasts. The drug dealers in their Nissans and heavy gold chains. Young men with arms slung out windows, lifting their chins and calling out to the girls, who’d pretend they weren’t trying to be noticed. Stereos blasting, music jumping from every open window. The bass lines so solid you could walk on them. You didn’t need a ride as long as that bass kept thumping, carried you down to where you wanted to go. Ride this line and it felt so good you knew you were gonna live forever, come back the next Sunday just to keep the thrill going. Young men and young women all looking fine, dressed, and ready. Eyes feasting on each other. Appraising and making offers, rebuffing or rebuffed. Affiliations made and broken. Sex or a hit or even the big prize, love, if the music and the weather were right. Crenshaw on Sunday. Like Mardi Gras. The candy store. Every carnival and holiday packed up into one tight bundle and rolled on down the wide boulevard. The young brothers and sisters cruising Crenshaw on Sunday. Nothing—at least that one perfect night of the week—could ever get in their way.

Jackie nodded as Lanier turned onto Degnan, noting that, indeed, this street was more lively. She saw the galleries and the stores that sold African goods. She saw several older men sitting in metal chairs, playing chess outside a coffee shop. Degnan was only a few blocks long, and soon they were right back on Crenshaw. “What did it look like around here thirty years ago?”

“More open,” said Lanier. “The houses didn’t look much different—they were nice, and a lot of blocks are still real nice, as you’ll see. Although just about everyone has bars on their windows now. There weren’t gangs, not the way we have them today. And a lot of these here businesses,” he waved his hand in front of Jackie’s face, “were open. This was just a nice, solid, middle-class area, pretty mixed-race even way back then, with a lot of black and Japanese folks. During the ’65 uprising, the looting didn’t start up here until the third or fourth day. It was a lot less widespread than the mess in ’92. But then, things were a whole lot worse in ’92.”

Jackie nodded, more in acknowledgment than agreement. She’d watched the ’92 riots unfold on TV. The rioters had made it to within a mile of her apartment, all the way up to Pico and Fairfax, extending into Hollywood just east of her, along La Brea and Western and Vermont. She’d been horrified and scared, though less certain than Lanier that this upheaval was somehow understandable. But now she remembered the TV newspeople talking about how “it” was coming closer to “us”; telling their viewers—as if they couldn’t see and smell for themselves—of the smoke that hovered over the city.

Lanier turned right onto a side street, and then turned left at the second corner. He’d been right—the houses were nicer here, and Jackie was surprised by how middle-class they all looked. The lots were big, the lawns neat, the eucalyptus trees large and looming, the houses well-kept and substantial. The trees that lined the sidewalk reached across the street and tangled their fingers together, so that when they drove down the block, Jackie felt like a child running through a gauntlet of older children in a game of London Bridge. At the next corner they took a left, and then another. Something was different about this block, but Jackie couldn’t put her finger on what it was. “Where are we going?” she asked.

Lanier slowed down and pulled over to the curb. He pointed out the window, saying, “Here.”

Jackie saw a tan stucco house with a black-tiled, sloping roof. There was nothing remarkable about it. “What’s this?”

“Your grandfather’s house.”

Jackie nodded. She thought, of course. But other than that, she felt nothing—no recognition, no connection. The only thing that struck her was that this house was bigger than the one the family moved to in Gardena. “It’s nice,” she finally said. She looked a minute longer. And as she looked, certain things became clear to her, the way a stranger’s features, once you learn she’s related to someone you know, suddenly appear more familiar. Jackie noticed the black tiles, the shuttered windows, the perfectly manicured bushes and bonsai-style trees. “That stuff—the trees, the tiles—that’s all Japanese.”

Lanier nodded. Jackie looked down the street and saw that all of the houses had the same bonsai-type bushes and trees. Many of the houses also had old Japanese-style doors, black strips of wood criss-crossing the white body of the door, like crust laid over a pie. A few places had window shutters modeled after screens in Japan, and stone lions placed on either side of the entrance. The roofs were black and tiled, some multi-layered and pagoda-style.

“This looks like Gardena,” Jackie said.

Lanier nodded. “There used to be a lot more houses like this, but most of them are gone now.”

After a few more minutes, he pulled away from the curb, and Jackie realized that she’d seen a picture of this house, of Lois and Rose as little girls, sitting on the lawn with a kitten between them. She stared out the window, feeling like a tourist in her grandfather’s life, and when they turned again, she felt a twinge of loss. She didn’t pay much attention to where the car was going until Lanier stopped in front of a boarded-up old building. He nodded toward it. “Your grandfather’s store.”

This time, Jackie reacted. She was afraid, she was curious, she wanted both to flee and to stop and look closer. She got out of the car and stood there for a moment. The store was free-standing— to the right was an alley and to the left, the back of the buildings on Crenshaw. It was bigger than she’d expected, not like one of the tiny bodegas she often passed on Washington or Pico. The building had obviously met with violence and fire—there were boards across the door and the plaster around each window was black and charred. The walls were covered with graffiti, black and indecipherable to Jackie. The faded black letters on the rusted white sign read, “Mesa Corner Market.” There were several crushed beer cans in the doorway, two or three broken bottles, and a scattering of glass vials with green plastic caps.

“Jesus,” she said. “How long’s it been like this?”

Lanier had gotten out of the car, and he came up and stood next to her, arms crossed. “Since the uprising.”

“That long?”

“The ’92 uprising. It was open a long time before then. Your grandfather shut it in ’65, but he sold it to someone else.”

“Has that owner had the place the whole time?”

Lanier shook his head. “No. He sold it again a few years ago to a Korean couple.” Lanier kicked at a can in front of him; it went skittering down the sidewalk. “I felt bad for them. The day after the store burned, the wife, Mrs. Choi, was standing out in front, looking at the mess and crying. A couple of the mothers brought back stuff their kids had taken from it—just little things, packages of cookies and cigarettes—and a few others helped sweep up the glass and the ashes. But they never reopened and I don’t know who owns it now. It’s been empty for the last two years.”

Jackie nodded, only half-listening. As she walked forward, getting close enough so that the front of the store blocked out the sky, she was thinking that this place, this shell of a building, was where her grandfather had spent twenty years of his life. She went right up to the door, raised her arm, placed her fingertips on the wood. It was cool and rough, a little frayed. Slowly, so as not to get a splinter, she flattened her hands against the board and closed her eyes. On the other side of that wood, her grandfather had struggled and sweated and laughed. She could almost see him as he’d been then, as she’d seen him in pictures—tan work pants, white shirt that was always slightly too large, crisp white apron, neatly tied and blindingly bright. Tan face, almost as brown as the skin of his field-laborer father, and shiny black hair, slicked back with Pomade. Her grandfather’s money had been made and lost here. Four teenage boys had died here. It seemed to Jackie that if she could just get inside, beyond the boards, the answers would all be available to her, scattered among the ashes. Or perhaps Frank himself would be there, sweeping, restocking the shelves, ringing up groceries for an afternoon customer.

Lanier watched her, glad that he’d taken this foolish girl by the head and forced her to look at her past. She seemed nice enough, concerned enough about Frank to be here today, but her parents, clearly, had sent her into the world without the nourishment of her own family history. Her past was like this neighborhood—still there, intact, but she had never bothered to visit. Never driven through its streets, taken in the beauty of its trees and houses. Let it sit there unexplored just down the road from her.

“Can we get in here?” she asked, not turning.

“No. It’s all closed up. And there’s really nothing to see in there anyway. It was all pretty much burned out.”

Jackie nodded. She took her hands off the wood and turned back toward Lanier, who was standing, a bit awkwardly, on the sidewalk. “Thanks,” she said. “I’m glad I saw this. It makes everything more real, somehow.”

Three young boys careened around the corner on bicycles, rode between them, then turned again and darted down the alley. Lanier watched them go. He and Cory always biked over around this time to see what Curtis was up to. “You know, a lot of times at this time of day your grandfather would be sitting outside with his friend Mr. Conway to greet the kids when they were coming home from school.”

“You think that’s how he met Curtis?”

Lanier shrugged. “Probably. Curtis and Cory lived a couple blocks from here and they would’ve walked by on their way back and forth from school.”

“What do you know about Curtis? Why did my grandfather like him so much?”

“I don’t know why your grandfather liked him, but I know why I did. He was always there, man. Always. He was solid.” And he kicked me in the ass when I needed it, Lanier thought. He paid attention to me, and wasn’t embarrassed to have me and his brother hanging around with him. With him I felt big, like I mattered. And so much of what I do now is still about him.

“What was his family like?”

Lanier sighed. “Complicated. I’m not sure their parents liked each other much. Bruce—my uncle—was from L.A., but he met Curtis’s mom when they were working in Oakland. Actually, Curtis was born up there, and his mother went back up there after he died. Anyway, Bruce and Curtis used to fight something awful. I don’t know what the problem was—Curtis was a pretty good student and didn’t get into any trouble. But he did whatever he wanted and hung out with whoever he wanted, and I don’t think that sat very well with his dad.” Nothing ever did sit well with Bruce, he remembered. Jimmy’s own mother didn’t, which meant that neither did Jimmy. Uncle Bruce was more frightening than any version of Jimmy’s father, drunk or sober. He had a way of making you feel like you were being beaten, even though he never raised a hand.

“Anyway,” Lanier continued, “Bruce and Alma, Curtis’s mom, used to fight a lot too. Usually about Curtis, I think.” But Alma, he remembered, could handle him. Fiercely loving but also aloof somehow, she was Jimmy’s first love. And Curtis’s. And everyone else’s.

“What’d they do for a living?”

“Bruce worked for Goodyear. When I was growing up, there were a bunch of factories and plants in the area. A lot of men walked to work—you could actually hear the five o’clock whistles. And Alma was a teacher. She ended up getting some important job with the Oakland School District after Cory graduated from high school, but back when I knew her, she was a teacher. Before that, she was a factory worker. And before that, she worked as a domestic.”

“My grandmother was a teacher, too. And my great-grandmother was a domestic.”

Lanier laughed. “My great-grandmother was a domestic, too. And my grandmother. And my mother. I guess that was the fate of most women of color back then.”

Jackie didn’t answer. She was surprised and a bit uncomfortable that someone from her family could be lumped together with someone from Lanier’s family, and from the Martindales’. Even though she knew that her grandparents, and great-grandparents, had lived in this neighborhood, she didn’t really think of them as part of it. Their stay here—and her tour—was only an accident, a fluke. They’d been interlopers, visitors, and now they were gone.

Jackie and Lanier walked back toward the car. Jackie noticed, across the street, more remnants of the earthquake—cardboard covering windows, broken glass sparkling on the lawns. But then, just as she was about to open her door, a string of small children, linked in pairs, came into view on the sidewalk on Crenshaw. There were a good twenty or twenty-five of them, and judging from their organized procession and from the four tired-looking women who walked beside them, they were a class from a local elementary school. The first children were halfway across Bryant Street when one of them yelled, “Look! It’s Mr. Lanier!”—and then suddenly children were breaking out of line, sprinting fullspeed down the sidewalk. About ten of them streamed toward him yelling “Mr. Lanier! Mr. Lanier!” and they all hit him more or less at once. “We saw a dead squirrel!” one of them announced. “Yeah,” said another, “and its head was all bloody!” “Mrs. Davis showed us all different kinds of trees!”

“Whoa, whoa!” Lanier said, laughing. But he’d come back to the sidewalk and dropped to one knee, giving the kids more access to him, and he seemed somehow to be looking at all of them at once, enclosing them all in his arms. The other children were still in the middle of the street, their line depleted and confused, and the women quickly herded them onto the sidewalk, calling to the kids who’d surrounded Lanier: “Shaniqua! Todd! Angelique! Get back here!”

But the children paid them no mind, even when Lanier instructed them to return to their class. They couldn’t take their eyes off of him. And as they kept telling him about what they’d seen and done that day, they all managed somehow to touch him—hand to his knee, arm on his shoulder, an elbow linked around his elbow.

“I’m sorry, ma’am,” Lanier said to the middle-aged, long-suffering woman who came over to retrieve her charges. “They’re in my after-school program.”

“I know who you are,” she replied. “They talk about you like you’re Disneyland.”

Because the kids refused to go back on their own, Lanier had to take them. He stood up with one child hanging onto his shoulders, a child tucked under each arm, and the rest of the kids clutching his shirt or pants. Like a many-headed, many-limbed creature, they made their way to the corner where the rest of the class was waiting. After he’d disengaged the last child and safely returned her to her partner, he came back down the sidewalk toward Jackie.

“They love you,” she said, smiling.

Lanier looked a bit sheepish. “Yeah, well, you know.”

But she didn’t; she hadn’t. The childrens’ obvious adoration of him, his tenderness with them, was a surprise, and a recommendation. By the time they reached the parking lot, Lanier’s usual face and voice and demeanor had already snapped back into place. But Jackie didn’t buy it anymore. She’d seen something that she wished to see more of.