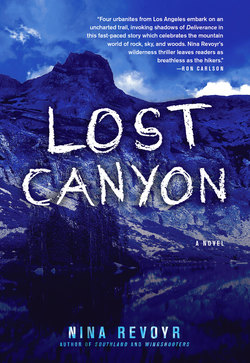

Читать книгу Lost Canyon - Nina Revoyr - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One

Gwen

The picture opened on Gwen’s computer, revealing a lake framed by pine trees, a backdrop of snow-covered peaks. A small stream flowed from the lake and when she looked very close, Gwen could almost see the water moving, the clouds drifting over the mountains. She imagined herself in the scene—the warm sun on her skin, the smell of pine—and felt her breathing slow, her shoulders ease. Just for a moment she forgot where she was—in a dingy building on 103rd Street in Watts.

Tracy’s e-mail had come with the subject line, Cloud Lakes Trip: Last-Minute Details! Although Gwen was about to step out of the office, she couldn’t resist checking the message. Besides the photo, there was a bullet-point list of food and supplies, plus directions to Tracy’s house. Gwen glanced at the list and looked back at the picture; then she picked up the phone.

“Tracy Cole,” came the voice on the other end. As always, she sounded focused and busy. Gwen could imagine her in her workout gear, standing arrow-straight behind the counter at the gym.

“Hey, Tracy, it’s Gwen.”

“Hey!” Tracy’s voice was friendlier now, although she still sounded poised for action—ready to run a marathon, or break up a mugging, or hang glide off a cliff near the coast. “You got my e-mail?”

“I did, thanks,” said Gwen. “It looks like I still need a few things. A sleeping pad, extra batteries. An extra fuel canister. How much is all of this going to weigh?”

“Maybe thirty-five pounds. A piece of cake. You’re not having second thoughts, are you?”

“No,” Gwen assured her, although she was. What had she gotten herself into? Gwen was a city girl, born and bred—she knew chain-link fences and concrete better than rivers and trees. And she spent most of her time in South LA, where she worked for an organization that provided counseling and after-school programs for low-income kids. Although Gwen had started hiking a year and a half ago, it had all been short and local—she’d never hiked a trail more than five or six miles long, and she’d never spent the night in a tent. This trip would be unlike anything she’d ever done before—a four-day, three-night trip into the Sierra backcountry, a real wilderness experience. She imagined how the pack was going to feel on her shoulders—like carrying a child piggyback, and never putting him down. But she needed this; she needed to do something different, to see a world that was not shaped by people. “I’m just not sure about carrying all that weight,” she said.

“You’ll be all right. Just load your pack up the next few nights and walk around the block.”

“Okay,” Gwen said doubtfully. She imagined the stares she’d get from neighbors. Backpacking had never been a part of her world. Most people she knew would think of it—if they thought of it at all—as an activity for tree-hugging granola types with excess time and money. It definitely wasn’t anything that black people did—especially not women.

Besides, all of this was easy for Tracy to say. Tracy was strong and fit—a combination of the Japanese sleek of her mother and the Idaho mountain man stock of her father. She’d been a star soccer player, an alternate for the US national team, and had followed that up with a slew of outdoor pursuits—rock climbing, mountain biking, snowboarding—that, in Gwen’s opinion, bordered on extreme. Now she was a trainer at SportZone, a physical therapy center and gym run out of a converted warehouse downtown, and she also had private clients on the side. Gwen had met her while doing physical therapy for a hyperextended knee, which she’d hurt during a volleyball game at the company picnic. Once she graduated from PT, she’d joined the fitness classes on the other side of the gym, and Tracy was the teacher.

“You know, I have an extra sleeping pad,” Tracy said now. This trip to Cloud Lakes had, of course, been her idea. “Don’t buy one. And I’ve got fuel and most of the group gear too. Is there anything else you need?”

“No, I think I’m okay.” Gwen appreciated the offer, though. She’d borrowed the backpack and a sleeping bag from someone at work—but she’d still had to buy a headlamp, a rain jacket, and some lightweight pants, not to mention a sturdy pair of hiking shoes. She wouldn’t be able to pay off her credit card bill that month, but one month of overage wouldn’t kill her. Much worse, she knew, would be to stay in the office all summer.

“Well, all right then!” Tracy said cheerfully. “I’ll see you at nine on Thursday at my place. It’s going to be beautiful, Gwen. Classic Sierra backcountry. Trust me. You’re not going to believe it.”

“I’m excited,” Gwen said. But she was nervous too. “Hey, who are the others again?”

“They’re all clients. A couple of married stock-fund managers, the Pattersons. Todd Harris, the lawyer. And Oscar Barajas, the real estate guy.”

“Don’t I know Oscar?”

“Yeah, he comes to my Tuesday morning class.”

Gwen was quiet for a minute and Tracy broke in again.

“Don’t worry! They’re nice people. I wouldn’t subject you, or me for that matter, to spending four days with a bunch of assholes.”

“Okay, okay,” Gwen said, laughing. “I’ll see you on Thursday.”

After she hung up, she sat thinking for a moment. What would she have to talk about with a lawyer and two finance people? But she shook these doubts off. She needed a change of scene, a mind-frame adjustment. There’d been a lot weighing on her this last year, ever since the loss of Robert, a kid from one of her groups. Thank God for this trip. Thank God for Tracy, who made Gwen get out and do things that she would never have done on her own.

Gwen had never really been into exercise. But as she’d lifted barbells and hoisted medicine balls and trudged up the stair machine in Tracy’s class, she was amazed at how much stronger she felt. Muscles she didn’t even know she had grew sore, and then firm. Her excess pounds fell away. For the first time in her life, her body didn’t feel like an encumbrance, or an enemy. And when Tracy invited her to join her twice-monthly hikes in the local mountains, Gwen had jumped at the chance. She’d been on a few hikes with the kids from work, but this was different. There was something about Tracy’s energy, her lust for adventure and her solid belief that any new skill or pursuit could be mastered, that appealed to Gwen. She had needed that kind of optimism, especially this last year. She hoped that some of it might rub off on her.

Gwen grabbed her purse, stepped out of her office, and headed toward the entrance. The building had originally been a hospital for the mentally ill, and that’s what it still felt like. The offices, converted from bedrooms, were windowless and claustrophobic. Half the overhead lights were burned out and the rest flickered unreliably. As Gwen passed through the front lobby, she saw the crack in the ceiling that was the shape of a lightning bolt; one good shaking from an earthquake might bring the whole place down.

She walked out to her car, a ten-year-old Honda. The weather was cool and overcast even though it was summer; she thought, not for the first time, that June Gloom was especially gloomy in South LA. She drove east on 103rd Street past the old train station, past the apartments for low-income seniors, barely glancing at the Watts Towers to the right, whose curling, colorful spires usually cheered her. Beyond Wilmington the broad street narrowed as it entered an area of small, rundown bungalows and apartment buildings, which faced the public housing projects across the street.

At Lincoln High School, she showed her ID to the security guard, who waved her into the lot. Then she walked across the concrete playground and into the ancient high school, which looked like a 1920s Department of Water and Power building that hadn’t been painted since it was built. She made her way down a long hallway, past a custodial crew scrubbing curse words off the walls and graffiti from the lockers, and into the administrative office. There, she was pulled into an inner office while the secretary dug up the papers she needed to sign—the new memorandum of understanding between her agency and the school, program completion forms for some of her kids.

As she went back out to the waiting room, a group of students arrived to sign up for summer school. Two of them were black, the rest Latino, reflecting the change in the neighborhood. Just a few years ago, Watts had still been mostly African American. But last semester, in Gwen’s youth leadership group at this school, she’d been the only black person in the room.

“Hey, Ms. Foster!” one of the kids called out. It was a student from the job readiness program that was run by her colleague Devon. “It’s Sylvia,” the girl said. “Sylvia Morales.”

“Oh, hi!” Gwen answered, summoning the upbeat, caring energy she always tried to have with the kids. “I didn’t realize you went here. You’re a junior now, right?”

“Gonna be a senior next year,” said Sylvia. She was a stocky girl, 5'8" or so, and she carried herself with a confidence that belied her surroundings. “I can’t wait to get out of this mess.”

“Are you coming to Devon’s group at the office this summer?”

“No . . .” Sylvia said, and now she glanced back at two other kids, another Latina and a black girl, both standing with their arms crossed and looking away like there was something else they’d rather be doing. “Actually, Lupita and Dawn and I were hoping to be in one of your groups. Sandra was in your leadership group this year—Sandra Gutierrez—and she told us we should join it for sure.”

“That would be great!” Gwen said, pleased in spite of herself. “Hi, Lupita. Hi, Dawn. I’m Gwen. It’s wonderful to meet you. I look forward to getting to know you next fall.”

And just like that, facades began to crumble. Lupita blushed and mumbled hello, and Dawn met Gwen’s eyes and smiled big.

“Just talk to your resource coordinator,” Gwen continued. “Or better yet, stop by our office and sign up with the receptionist.”

“Will you be around on Thursday?” Sylvia asked. “We could come by after school.”

“Actually, no. I’m taking a little vacation.”

“Really? Devon said you’re always at work.”

“Only most of the time,” Gwen said, smiling. “But yeah, I’ll be gone for a couple of days. I wanted to get away.”

“Get away from all this?” Sylvia asked, striking a pose like a game show assistant. With the sweep of her arms she took in the office, the school, the neighborhood.

Gwen laughed and promised to see the girls the following week, and to save them spots in one of her groups. Now she remembered hearing about Sylvia from both Devon and Sandra, who’d been one of her hardest cases this year. These teens seemed so tough on the surface, but softened when you took the time to see them. Bright kids, all of them, full of potential, and as she walked back to her car, she felt cheered.

But as Gwen drove back toward the office by a different route, she remembered what those kids walked back into. This neighborhood felt like a bombed-out city, deserted after a war. Trash was piled everywhere. There were broken TVs and discarded tires, old mattresses, dirty clothes. Greasy food wrappers balled in gutters or fluttered away down the street. Doors and windows were covered with iron bars and particle board. The threat of crime hung in the air like a layer of smog; just last week there’d been a lockdown at the office because of a nearby shooting, and the week before, a man on a bicycle had held up two of her colleagues as they left a client’s apartment. Inglewood, where Gwen lived, had its own share of troubles. But here, it felt like there were no rules at all. You always had to be on guard working in this neighborhood. You had to be prepared for the worst.

And yet, that was exactly why Gwen liked working in Watts—because the kids here had so much stacked against them. When she kept a young boy from joining a gang; when a girl she worked with made it to college, Gwen felt a huge sense of triumph and vindication. She’d had a rocky road herself when it came to school and family. No one had really expected anything from her, and no one expected anything good from the kids she helped. They were kids that other people thought expendable.

She turned onto a street that led into the housing project where Robert and his family had lived. It was a labyrinth of two-story bungalows that might have once been green. As always, she was struck by the desolation. On the dead grass between the units were old sinks and barbecue grills, piles of rusted bike and auto parts. Laundry waved from clothes lines, colorful items that stood out against the gray sky, like flags hung in surrender. A few proud residents struggled mightily against their surroundings—their entryways were swept clean, with maybe a potted plant or two—but this couldn’t make up for the heavy gates over the doors, the paint flaking off the walls, the chunks of roof that collapsed with each rain. Once she had to stop for a legless woman in a wheelchair. Twice she slammed her brakes to avoid a loose dog. There were kids everywhere—youths circling on bikes, toddlers sitting on stoops with their mothers or grandmothers, a group of middle school kids throwing around a football. A dozen little ones waited in line for the single swing on an otherwise broken play set.

Gwen wove her way through the development, looking but not stopping when she passed the row where Robert had lived. Once he had been one of those kids, sitting on his stoop. Now he was gone, and she couldn’t bear to look for very long at the place where he should have been, but wasn’t.

Gwen loved her job, but lately she’d been feeling overwhelmed. It seemed like no matter what they did, no matter how many kids they helped, there were always others, so many others, who couldn’t be reached. It was like trying to rescue people from a flood or tsunami—you might be able to pluck one or two out of the swirling waters, but hundreds more got swept away right in front of you.

And the neighborhood itself didn’t help. In this community, it was hard for Gwen and her colleagues to preach about the promised land of college and a well-paying career, to instill that kind of faith, when no one in most of these kids’ everyday experience had ever laid eyes on it or breathed its different air. There was no way a kid could walk into that school, or through Gwen’s office building, or down these streets, and feel anything but second-rate. Now Gwen was starting to feel that way too.

Just as she turned into her parking lot, her cell phone rang. She picked it up and saw the caller ID—Alene Richardson—and let it ring one more time before she answered.

“Hi, Mom.”

“Oh, hello, Gwen,” her mother said, sounding distracted, as if Gwen had been the one to call her. “Are you at work?”

“Yes.” Where else would she be?

“Good, good. I was just calling to remind you that Dana’s birthday is on Friday.”

“Yes, Mom, I know. I sent her a card today.”

“Oh, wonderful! Thank you. You know how lonely your sister gets up there at school. It’s good for her to hear from her family.”

Gwen tried to quell her irritation. Her sister, she knew, was just fine. Twelve years younger than Gwen, she was now a first-year student at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. Dana had been raised in a totally different era of their mother’s life. She’d grown up in the house in Ladera Heights that had just been a stopping point for Gwen; had been lavished with clothes and trips and extracurricular activities; had been part of Jack & Jill, a young women’s leadership group at church, the AKAs at Berkeley. Now, at twenty-four, Dana’s birthday was still celebrated with as much fanfare as if she were a child. Yet there had been years in Gwen’s own childhood, when she lived with her great-aunt, that Alene had forgotten Gwen’s birthday altogether.

“I’m not going to be able to call her on Friday, though, Mom,” Gwen said. “But I mentioned that in the card.”

“Why not?”

“I’m going on my backpacking trip this weekend. Remember?”

A tense silence. Then a sigh. “Yes, now I recall. You’re really going to do that, Gwendolyn?”

“Yes, Mother, I’m really going to do that.”

“It just sounds so . . . uncivilized. I mean, how will you bathe? How will you . . . use the restroom? Where will you sleep—on the ground?”

Gwen didn’t answer, partly because she wondered these things herself. She stared out past the fence that enclosed the property and over toward the railroad tracks, where a mangy brown dog picked hungrily through a mountain of trash.

“I just don’t know how you got this idea in the first place,” Alene continued. “It’s not the kind of thing we’ve ever done.”

Gwen thought wryly that her mother had little idea of what she’d done, but she kept this observation to herself. “Chris and Terry Nelson went on backpacking trips every summer,” she said, remembering her mother’s neighbors.

“Yes, but they’re boys,” Alene replied. She didn’t add—although Gwen knew she thought—and white. “And speaking of boys, are there any men going with you?”

“Yes, three men.”

“Couldn’t one of them carry your things?”

“No, Mom. They’ll have their own backpacks.”

“Well I don’t know what kind of man would let a woman carry so much weight.”

She stayed silent, waiting for her mother to launch into a lecture about Gwen’s nonexistent love life, but she didn’t.

“And is a hotel too expensive?” Alene asked. “Is that why you’re sleeping outside?”

“It’s not that. We want to be outdoors.”

“I really wish you’d do something that would pay you a decent salary.”

And here we go, Gwen thought. Out of nowhere. “I like my job, Mom.”

“You’ve done your part giving back, don’t you think? I just worry about you in that dangerous area, with all those desperate people. You could always go to business school at night, you know. Or even law school. Stuart and I could help you.”

“Thanks. Listen, I have to go. I’ll give you a call before I leave.” Gwen hung up, took a deep breath, and got out of the car.

She never failed to rile her, Gwen’s mother. In the space of five minutes, Alene had managed to denigrate both the white people whose unclean habits Gwen appeared to be emulating, and the black and Latino kids with whom she worked.

Gwen was born when her mother was seventeen. Although no one ever talked about it, it was believed that her father had been the vice-principal at Alene’s school. Alene had dropped out, fallen into the grip of alcohol and God knew what else, and eventually disappeared, so from the time Gwen was three until just after she turned twelve, she had lived with her great-aunt Emmaline in Inglewood. It was Emmaline, a retired mail carrier, who’d come up with Gwen’s name, in honor of the famous poet. And it was Emmaline who’d passed on family stories—of Gwen’s great-grandfather who’d left Alabama for Chicago in the early 1900s; of her ancestor Phillis, who’d escaped from slavery in Tennessee and fled up to Ohio, where she’d given birth to Emmaline’s grandmother. For much of her childhood Gwen only saw her mother two or three times a year, and sometimes not at all.

When Emmaline passed away, Gwen lived with two foster families—first the Grandersons, a black family in Culver City, and then the Weisses, a Jewish family in the Valley. Both families had been kind to her, but by the time Gwen was fifteen, all she wanted was to live with someone who wasn’t paid to take care of her.

And then, almost miraculously, Alene reappeared. She’d sobered up, earned her GED, gone to college. She’d eventually gotten a master’s degree and started a job with a food company. She’d married Stuart Robinson, whom she’d met at their church, and given birth to another child. When Gwen went to live with them soon after her fifteenth birthday, the Alene she met was so different from the one who had left her that it was almost like she’d been placed with another foster family. Her own experience had made Gwen shy away from the idea of having children. There were enough kids in the world already, she thought, too many of them unwanted.

* * *

After telling the receptionist that the girls from Lincoln might drop by, Gwen made her way back to her office. She called up the image of the lake on her computer again and tried to recapture her sense of calm. But the scene was flat now; it had lost all its power. Damn her mother, she thought. Damn her for so swiftly poisoning even this.

She brought her mind back to where she was, the office where she spent so much time that she sometimes inadvertently called it “home.” On the walls there were pictures of her colleagues at various work events, a certificate naming her employee of the year, a framed commendation from the city councilman for her outstanding work with youth. On her bulletin board, there were photos of kids who’d been in her groups, and school portraits of some of her colleagues’ children.

At the corner of the board, closest to her, was a picture of Robert. He was posing on a rock high up on a hiking trail with all of LA spread out behind him. His hands were on his hips and his chin was raised at a jaunty angle, as if he were a conquering hero. He looked beautiful and ridiculous, pleased with himself and with the world. Gwen had taken this picture two weeks before he died.

Robert had been in seventh grade when Gwen first met him; he’d been referred by a therapist at his school. A tall, gangly kid, he’d shown up for group sessions in threadbare clothes, with holes in his worn-out sneakers. But he was unfailingly polite, and he always seemed to speak in complete paragraphs, using words—sustainable, honor-bound, erudite, Darwinian—that were almost comically formal. When Gwen finally asked him what had brought him to group, he answered only, “I was suspended for fighting.”

She couldn’t fathom the idea that this gentle kid was a fighter, and so she tracked down the school therapist. That was how she learned that Robert and his little brother Isaac had bounced around to several homes as their mother fled an abusive relationship. Robert had seen the man hold a gun to his mother’s head; he’d watched him break her arm. He’d gotten into several fights at his new school, the therapist said, while standing up for girls when boys harassed them.

Robert had always been a good student, so he didn’t need help with academics. But he was awkward and shy and down on himself, so Gwen connected him with other activities—Devon’s job prep group, a digital media class, and a group that went on outings, like that hike in the local mountains. He stayed in her youth leadership group through middle school and high school, where he got mostly As and a couple of Bs. In his senior year he applied to UCLA, and when his acceptance letter arrived, there’d been an impromptu celebration at her office—cupcakes and soda and teary speeches from the staff, Robert grinning and embarrassed at the attention. He seemed like the ultimate success story—a black boy from Watts who’d grown up in extreme poverty, and who had made it to a top-notch university.

Then Robert showed up to group one day with a fresh black eye. He wouldn’t talk about what happened. But Trey, another student, told her that some boys had started bugging him again, a couple of the same ones from back in seventh grade. Robert was skinny and nerdy, too into his books—he thought he was something special. He didn’t try to get with girls; there must have been something wrong with him. Gwen went to talk to the principal but he just smiled and nodded absently; he was new to the area, from Maine or Maryland, and he said the boys should “work it out themselves.”

A few days later the boys cornered Robert in the locker room. They stripped off his clothes, knocked him around, and left him there, naked. There was speculation that more might have happened but no one knew for sure. When the school staff questioned Robert, he just shook his head, refusing to talk.

Gwen tried to get him to open up, to no avail. He’ll tell us when he’s ready, she’d thought. He was subdued for several weeks, but then he seemed to turn a corner, and everyone was cautiously relieved. This was a terrible thing, but he’d been through worse, and he’d get past it; he always did. As the school year wound down he grew more cheerful again; he almost seemed at peace. He was talking about plans for the summer, and they’d even gone on that wonderful hike. That was why everyone had been so stunned when Robert hanged himself.

It had happened a little more than a year ago, the second week of June, and Gwen still felt completely undone. All these months later, she still asked that question that people ask and never get an answer to: Why? And even more, particular to her: How could I not have known? It was easy to say in retrospect that she had always sensed Robert’s sadness; that there was a stillness in him that she couldn’t touch or understand. And maybe, with his recent troubles, that sadness had tipped over into despair. But mostly what she remembered was his hopefulness. She couldn’t believe that he was not coming back; she kept expecting him to walk through the door of her office.

But then she did believe it, and she believed it still. Robert was gone and he wasn’t returning; he’d chosen to take his life. And besides the feeling of loss that still threatened to swallow her whole, Gwen couldn’t get over the fact that she hadn’t done more to help. She should have made him tell her what had happened; she should have forced that principal to do his job. She should have told Robert that no matter how bad things seemed now, they’d get better; the trouble would pass.

Gwen looked back at the picture and her eyes filled with tears. Robert had overcome so much, and he had everything going for him—good grades, the toughness to survive a difficult home life, a future that was bright and limitless. If he couldn’t find a reason to keep going, what hope was there for the other kids she worked with? Why did she even bother? Why risk her own safety every day for the sake of kids and families who were so deeply mired in problems that they were never going to get better? She didn’t know what to do anymore with her helplessness, her grief. Now her eyes returned to the picture of the lake. Yes, she thought as she looked at it. Yes, she needed to get away from all this.