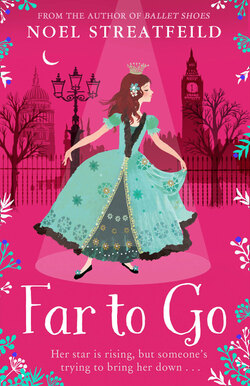

Читать книгу Far To Go - Noel Streatfeild - Страница 9

Chapter Three THE RED DRESS

ОглавлениеSir John and Lady Teaser and their daughter lived in spacious apartments over The Dolphin Theatre. It was, Sir John found, infinitely less tiring to live where he worked than have to drive to and fro to somewhere more fashionable, which was what Lady Teaser would have liked.

That Tuesday morning Sir John was enjoying a late breakfast when Lady Teaser swept into the room. She gave him a kiss.

Lady Teaser – her name was Ada – was an imposing-looking woman of a statuesque type. She had been an actress and had made a name for herself in a small way. But when she married Sir John Teaser she had given up her career for she was sure, if they both put their minds to it, that John would rise to be head of his profession. Because she had stopped acting that did not mean she had lost all ambition: she was very, very conscious that if she had gone on, she too might have reached the heights. Anyone who knew her and forgot this was making a very great mistake.

Now, as she had come in and because the day was beautiful and Ada, judging by the kiss, in a good temper, Sir John turned the conversation to his new play.

‘I’ve left the sorting-out of possible little girls to Tommy. He won’t let any of promise pass by him, but it is proving difficult to find exactly the child I want. He has had no luck so far; I gather they are all curls and dimples.’

There was a pause, which Sir John prayed Ada would fill, but when she spoke it was not to say what he wished to hear.

‘If you are still hoping I will allow Katie to play the part, you are wasting your time. Our little girl is being brought up to be a fashionable young lady. When she is old enough she will be presented at Court, and later she will marry a suitable husband, preferably a member of the peerage …’

Sir John laid a hand on Ada’s shoulder. ‘I know, dear, that is what you hope, but think back to the old days when you were an ambitious child, imagine what you would have felt if you had been given the chance to play the leading part in a beautiful play.’

Ada shook his hand off her shoulder. ‘When I was a child the question did not arise, and if it had, my father would not even have considered it.’

Sir John tactfully did not point out that Ada’s father, a poor man, would probably have jumped at the offer. ‘I shall not override your wishes, Ada, you know that, but I do beseech you to think of Katie. She is an exceptionally gifted child and, though she has heard nothing from either of us about the part of Anastasia, there must be talk, you know what servants are.’

Ada nodded.

‘If necessary I will tell Katie the whole truth. She will be angry with me for she believes herself to be an actress, but I do not want Katie to lead the life we led. You may have forgotten but I have not, those dreadful theatrical lodgings in which we stayed when we were first married. The mice and the rats,’ she shuddered, ‘the vermin in the beds where we lodged. By the time Katie was born, things had improved a little and, although when small she travelled with us, I suspect she has forgotten the discomforts and the smells. I have only one daughter. Is it not natural I should wish to keep her away from those sordid things that you and I remember?’

Sir John knew he was beaten. He took his watch out of his pocket. ‘I’m going down to see what news Tommy has. I believe he’s seeing another child this morning.’

Lou had only one room. She shared the kitchen and lavatory with the fourteen other tenants. Fortunately her bed was big so Sarah squeezed in with her. Margaret slept on a borrowed mattress on the floor.

Because the sisters were both members of the profession, as they grandly described being actresses, the next morning belonged to Margaret. Seeing a manager about a part was important, and everything else had to be put on one side for it.

First there was a discussion about Margaret’s hair. For Fauntleroy it had been dyed with peroxide but now the dye was growing out and Margaret’s original chestnut hair was showing at the roots. Lou ran her fingers through Margaret’s curls.

‘Lovely hair it is.’

‘If I slip out quick,’ said Sarah, ‘I could get more peroxide. Wouldn’t take long to do.’

Lou thought about that. ‘Very high class The Dolphin is, I wouldn’t think that Sir John would fancy dyed hair, not on a child.’

Sarah gave in. ‘After all, this Mr Smith who is seeing her will be used to hair dyes and that, seeing it’s a theatre, so he’ll know it could be fixed whatever colour was wanted.’

Next came the problem of what Margaret was to wear. The choice was small. She owned one blue pleated skirt worn with a darker blue knitted jersey. Both were the worse for wear. She had two cotton frocks made for her by Sarah. They were of the cheapest cotton but more or less in the fashion, for they came well below the knees and both had a little frill round the bottom, but it was too late in the year for cotton frocks. There were also two pinafores beautifully made by Sarah from some odds and ends of muslin and lace left over from stage dresses.

‘The cotton frocks are out,’ said Sarah, ‘for she hasn’t got a coat.’

Lou was not a person who gave in easily. After all, was she not second to the wardrobe mistress at the London Hippodrome, where could be seen the most lavish production of Cinderella ever staged? Now, easing herself into the only chair big enough for her, she gave herself to deep thought.

‘She’s a rare one for seein’ the way out of blind alleys is Lou,’ Sarah whispered, ‘which of course she often has to do in her position.’

Suddenly Lou, who had for a few minutes appeared to be asleep, jerked upright.

‘I have it. There’s me crimson. I don’t know when I last wore it.’

She forced herself out of the chair, went to her cupboard and, after some fumbling, produced an armload of dress. It was made of material called bombazine and was the same red as a pillar-box. She had worn it in the days of bustles so there was a quantity of material in it.

‘There!’ she said. ‘Isn’t that striking?’ It was indeed striking, perhaps too striking, for she added: ‘She could wear one of her pinnies over, that would tone it down.’

‘Can we make it in the time?’ Sarah asked doubtfully.

Lou looked despisingly at her sister. ‘Time! I could make four in the time if I had to. Now, clear the table …’

They pulled the table out from the wall and pushed aside the remains of breakfast. Then Lou lifted the dress on to the table.

‘I’ll cut it out, then you tack it together, Sarah, then I can run it round to the theatre to finish it on one of their sewing machines. You have an iron ready to press it and it will all be Sir Garnet.’

And, as far as Sarah was concerned, it was all Sir Garnet when at 11.25 a.m. she and Margaret arrived at the stage door of The Dolphin Theatre. Margaret was less happy. She was not herself in the scarlet frock, which was somehow stuffy and clung to her in the wrong places.

‘Cheer up, dear,’ said Sarah, ‘you look ever so nice. I’m sure they’ll take you.’ Then she opened the stage door and said to the doorkeeper: ‘Miss Thursday with an appointment to see Mr Smith.’