Читать книгу Domestic Arrangements - Norma Klein - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Six

Daddy’s birthday is on Saturday, October 27. I made him a collage calendar just like I used to. I love making collages. What I do is trim things out of magazines and move them around till I get an idea. Then I paste them on and draw connections with black India ink, figures that hold the design together. I like using 11-by-14 smooth white heavy paper; it has a good feeling to it. On the corner of each page, I paste a little month from a calendar.

Daddy used to want me to be an artist. I guess it was because when I was little I loved to draw. He’d take me around to art galleries and say to the owners, “Someday my daughter’s work will hang here.” I guess he was half joking, but it made me uncomfortable, even then.

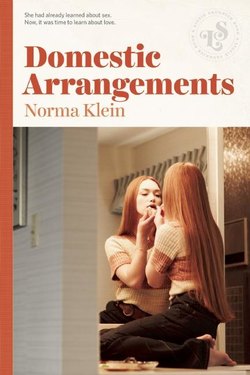

I like it that Daddy is so proud of me and thinks I’m so terrific, but sometimes I think he overdoes it. I feel that with my acting too. Daddy used to act some in college and summer stock, and when I first got the part in Domestic Arrangements, he was ecstatic. But then he wanted to go over my lines with me every night and tell me how he thought I should say them. The thing is, he wasn’t the director and I didn’t want two people telling me what to do. But also, I wanted to figure it out myself. Mom says it bugs her when Daddy lectures at her. She says he doesn’t even realize he’s doing it; he just likes to tell people what to do . . . that’s why he became a director. I think it hurt Daddy’s feelings when I told him I didn’t want to go over my lines with him. I told him Charlie had said I shouldn’t, but I think he knew it was partly me.

Daddy’s first wife, Dora, was ten years younger than him, just like Mom is. Mom says Daddy has a Pygmalion thing with women. He wants to take them as shapeless lumps of clay and mold them into some ideal image. I think he wants to do that with me too, a little. But I don’t want him to. I want to figure out how I want to be myself.

Deel said she’d make the Dobos Torte if I made the praline cheesecake. We both worked in the kitchen all Friday afternoon the day before the party. Luckily we have a big kitchen. The praline cheesecake recipe is from Mom. It’s an old southern recipe. What’s good about it is it has brown sugar, and anything with brown sugar is good. Plus it has pecans chopped up into it. When it’s done you rub maple sugar over the top, sort of massage it lightly. Everybody always loves it, Daddy especially.

Mom fixed up our terrace with balloons that had “50” printed on them. She tied them to the railing, but one got loose and floated away. We don’t have a great view from our terrace since we’re on 87th and Riverside, but it’s nice being up high. In the summer we eat out there and Daddy plants tomatoes.

Mom told Daddy about the party Saturday morning because she didn’t think he’d like it if it was a total surprise.

“Happy birthday, Daddy,” Deel said. We both came into their bedroom. Deel gave him her present first. It was a new book of Cartier Bresson’s photos.

“This is really lovely, Delia,” Daddy said. He was sitting up in bed, his hair a little rumpled. “It must have cost a fortune.”

Delia smiled. She’s very good about money. She saves a lot. Over the summer she worked at Fortunay’s, a soda fountain near our house, and earned over four hundred dollars.

Then I gave him the calendar I’d made. Daddy looked at each page carefully. He smiled at a lot of them. “I love it, Tat,” he said, hugging me. “It’s wonderful.”

I was glad Daddy didn’t get more excited about my present than Delia’s because I knew she’d be jealous then.

Mom gave Daddy a work shirt to wear on the terrace while he’s gardening. It’s navy-and-white striped and ties in front. Daddy tried it on. It looked funny, sort of like he was a nurse; it had big pockets. “I’ll feel very Tolstoyan,” he said. He kissed Mom. Mom always says she wants to zap up Daddy’s wardrobe. She gives him violet turtlenecks and funny ties with eyes on them; he doesn’t always wear them.

After breakfast Mom told Daddy about the party. She’d been afraid he might not like the idea. He’s not so much the party type. He doesn’t mind small parties with people he really likes, but he doesn’t like big parties with swarms of strangers, the way Mom does. Mom says she always thinks she might meet someone who’ll change her whole life. Daddy says but has she ever met such a person, and Mom says no, but that doesn’t mean it’ll never happen. Anyway, for Daddy’s party Mom invited fifty people since that’s how old he was, but they were mostly people they’d known a really long time.

Charlie sent Daddy a telegram, which arrived at noon. It said: “Come on in, the water’s fine.” Daddy said what he meant by that was that Charlie was fifty already and it wasn’t so bad.

“You don’t look fifty, Daddy,” Deel said.

“Not a day over forty-nine, huh?” Daddy said, crunching on a stalk of celery.

“I think you look forty,” she said.

“Forty?”

“Yeah, really . . . Lucia’s father is forty-two and his hair is all gray, all of it.”

Daddy’s hair is only a little gray. “Well, that’s hereditary.”

“It’s your personality that counts,” she said. “You act young.”

“I do?” Daddy said, surprised.

“I don’t mean in a bad way,” Deel said. “But you have a playful spirit.”

“That’s true, I do, don’t I?” Daddy said. “Why are you smiling, Tatiana, sweets? You don’t think I have a playful personality. You think I’m dour and mean.”

“No,” I said, laughing.

“She thinks I’m an ogre,” he said. He made this sad face he used to make when we were little and he used to entertain us telling us stories.

I went over and kissed him. “I don’t, Daddy, really.”

Mom and I decided to wear our Laura Ashleys. Mom’s is made of a material called lawn, which is a very fine cotton. It has a high neck and long sleeves ending in lace. Mine is dotted Swiss with puffed sleeves and a sash that ties in the back. Deel would never in nine million years wear a dress like that. Even on fancy occasions, like this, she just wears a newish pair of jeans and maybe her Indian silk shirt. That’s as fancy as she ever wants to be.

When Mom and I came into the living room, Charlie had arrived. He’s Irish and he dresses in a funny way—bright green ties and tweed slacks with lots of colors in them. “Visions of loveliness, coming at me from all directions!” he said, staggering backward. “I’m in a dream . . . is this West 87th Street?”

“Let me get you a drink, Charles,” Mom said.

Charlie followed Mom into the kitchen. “She can talk, she can walk . . .” He winked at Daddy, who was wearing his Tolstoyan work shirt with a navy turtleneck underneath. “Cheer up, kid, fifty is young.”

“That’s what I’ve been telling him,” Mom said.

“Life begins at whatever age you are . . . till you’re dead,” Charlie said. He grabbed me by the waist. “What do you do to this girl?” he said. “Look at her! She gets more radiant every second! It’s not possible. You’re giving her too many vitamins . . . Tatiana, stop taking those vitamins!”

Mom came in with the punch bowl. Deel and I had cut up strawberries all morning to float on top. Daddy and Charlie clinked glasses.

“To you, Lionel,” Charlie said.

They drank and then Mom raised her glass. “To us,” she said.

Daddy looked at her, puzzled.

“It’s our anniversary,” Mom said.

“What?” Daddy frowned. “But our anniversary is in—”

“The anniversary of when we first slept together, to use the euphemism of that bygone age.”

“It was on my birthday?” Daddy said, still looking surprised.

Mom nodded and sipped her punch. “You see what a big impression it made on him,” she said to Charlie.

“How old was I?” Daddy said.

“Thirty-three.”

Daddy groaned. “Was I ever that young?”

“Where was it?” Deel asked. She loves to hear stuff like that.

“In Lionel’s office.”

“Did I have a couch in my office?” Daddy said. “I thought it was a kind of—”

“No couch,” Mom said.

“God, I must have been young.”

“Daddy, how come you don’t even remember?” Deel said.

“Well, I . . . What were the circumstances?” Daddy said. “Refresh my memory.”

Mom was smiling. “I was interviewing you . . . for the school paper.”

“Oh God, yes . . . of course.”

“Why’d you want to interview him?” Charlie asked.

“Oh, I didn’t . . . but I thought it would be a good ploy, you know, drawing him out, asking breathy questions.”

“It worked, of course?” Charlie said, glancing at Daddy.

“Like a charm.”

“Wait a minute,” Daddy said. “My memory of this is totally different.”

“What do you remember, Daddy?” Deel asked.

“Well, I remember Amanda in my class . . . she was an excellent student,” he said to Charlie.

“I can imagine,” Charlie said, smiling at Mom.

“She was quiet, slightly demure, even . . . asked provocative, intelligent questions, wrote excellent papers. You got an A, didn’t you?”

“B,” Mom said. “You were afraid if you gave me an A, people would think it was because we were—”

“You deserved an A,” Daddy said. To Charlie he said, “She definitely deserved an A.”

“I’m sure she did . . . A plus, if it were up to me.”

“I thought you were married to Dora then, Daddy,” Deel said.

Daddy looked uncomfortable. “Well, it was unraveling . . .”

“What was Dora like?” Deel persisted.

Daddy gazed off in the distance. “Beautiful . . . in the beginning.” He looked at Charlie. “Didn’t you think?”

Charlie cleared his throat. “Beautiful? No,” he said flatly.

Daddy squinted. “Fragile, dreamy, delicate . . . a porcelain figurine.”

“Maybe,” Charlie said. “I see what you’re getting at. A few cracks by the time I met her.”

“Lionel idealizes women,” Mom said.

“He does, doesn’t he?” Charlie said. “Bless his heart.”

“So, did Mom, like, seduce you when you were married to Dora?” Deel said. I could tell she was getting all excited, hearing all these details of their private life.

“Well, kind of, I guess,” Mom said.

“I always thought I seduced you,” Daddy said.

Mom smiled. “Men like to think that.”

“When really,” Charlie said, “they’re just leading us docilely along, tugging gently at the rings in our noses.”

“I love that image,” Daddy said, wryly.

“Did Dora mind?” Deel persisted. “I mean was it like in The Way We Are Now with Dr. Morrison and Myra?”

Daddy choked on his punch. “Well, I’d hate to think of my life being like a third-rate soap opera,” he said.

“Lionel!” Mom stared at him.

“What?”

“A third-rate soap opera?” Mom’s cheeks were all pink. She really looked mad.

Daddy looked like he knew he’d said something dumb. “No, third-rate was . . . I just meant—”

Mom wheeled away. “We know what you mean. Just like you think Domestic Arrangements is a third-rate film. Everything is third-rate to you.”

“Darling, no.” He tried to sound soothing.

“Well, tell Charlie,” Mom said, still mad. “Tell him all you were saying about how Tat is going to be exploited. Tell him!”

“Exploited?” Charlie said, looking at Daddy. “In what sense?”

Daddy really looked embarrassed. “No, it’s just . . . that scene, you know, the hair-dryer scene. I just thought—”

“Lionel,” Charlie said. “That scene is devoid of even the vaguest trace of sensationalism. I’d bring my Aunt Minnie in from Iowa City to see it. That scene will make people weep.”

“Weep?” Daddy said.

“Yes, weep,” said Charlie. “That expression with which Tatiana looks up at Winston, that wide-eyed, soft, radiant expression . . . there’s no dirt there. Anyone who can find anything salacious in that scene is a dirty old man.”

“See!” Mom said triumphantly to Daddy. To Charlie she said, “He just thinks if it’s not Chekhov, it’s third-rate.”

“Look, you have two choices in life,” Charlie said. “You can spend a vast amount of time and energy inveighing against the way things are, or you can learn to live in the real world and make the best of it. I’m of the latter school.”

“Me too,” Mom said. “Sure, I could have spent the last decade auditioning for wretched little earnest off-off-Broadway plays which would run three seconds, and get wonderful reviews in the Voice, but so what? What would that prove?”

“Of course,” Charlie said. “Instead you’ve used your skills, you’ve kept them alive.”

“Exactly,” Mom said.

Daddy looked sheepish. “People, please! I am being falsely maligned. Of course one compromises, I’m not saying that. I’m only saying it’s important to keep the flame burning.”

“What flame?” Mom said.

“The flame of idealism, of art, of something wonderful.” He gestured vaguely.

“Listen,” Charlie said. “This movie is wonderful. This is a wonderful movie, and your daughter is a wonderful actress. Okay? This is fact. I don’t say it because I made it, I don’t say it because Tatiana is your daughter. I say that because I came out of that screening shaking.”

“Okay,” Daddy said. “No, we’re eager to see it, Charlie.”

“I am,” Mom said. “I’m eager.”

I looked around the room. Deel wasn’t there anymore. I went to look for her. The front bell had started to ring and a whole lot of people poured in. Deel was in her room, sitting on the edge of her bed, smoking a joint.

“How come you’re in here?” I asked.

“You want me to get stoned in front of Daddy?”

“No, I just meant . . . how come for the party?”

“I hate parties!” Deel said. “I hate all their phony, dumb friends.”

“Simon’s coming,” I said. “You like him.” Simon always plays Scrabble with Deel. They’re both very good. They play in French, even.

“He’ll be busy. He won’t want to talk to me if he can talk to someone his own age. Anyway, Mom’ll probably be flirting with him like a maniac all afternoon.” She handed me the joint. “Want some?”

“Okay.” I inhaled a little. I’m very suggestible when it comes to pot. A few puffs and I’m off.

“That is so sick about Mom and Daddy,” Deel said.

“What?”

“She took him away from his wife. What a seedy thing to do!”

“Well, but he said their marriage wasn’t that good . . .”

“Yeah, sure . . . they fucked in his office! You heard her.”

“Well, I guess she liked him a lot,” I said mildly. It’s hard to argue with Deel when she’s in that kind of mood.

“Yeah? She probably just wanted to get his scalp for her belt,” Deel said, puffing ferociously.