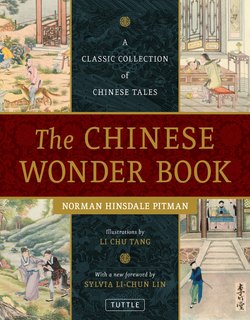

Читать книгу The Chinese Wonder Book - Norman Hinsdale Pitman - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

BY SYLVIA LI-CHUN LIN

My mother was a wonderful storyteller. On summer evenings, when it was too hot to stay indoors, my sisters and I would hose down our cement front yard with cool water. Then, after dinner, we would spread straw mats on the ground, bring out a chair for our mother and a tin of coiled mosquito incense, and lie on the mats, looking at the twinkling stars as my mother told us many of her stories. One of her favorite stories was called The Gentleman Snake, a Chinese version of the Beauty and the Beast. Whenever we asked her to tell this story, she would first say that we’d heard it so many times that our ears were probably filled up with it. But then she would slowly wave her palm leaf fan and begin the story, complete with interruptions—silly questions and comments—from us:

“A long, long time ago, there was a merchant who had three daughters. One day he was going on a business trip and asked what they wanted him to bring back. The first two wanted beautiful clothes and fancy jewelry, while the youngest one asked for nothing but the first pretty flower he saw on his way home.

[“Mom, why does the youngest daughter want only a flower?” I asked.

“Because she likes flowers.”]

“The merchant finished his business in the city and found the gifts for his first two daughters before setting out for home. But he did not see any flowers, let alone a pretty one. Just when he was despairing over the likelihood that he would have to disappoint his favorite daughter, he saw a great mansion encircled by a high, red-brick wall, over which the most beautiful flower he’d ever seen was hanging.

[“Mom, what kind of flower was it?” I asked.

“I don’t know.”

“Was it a rose?”

“I don’t know.”

“What does it matter? Why can’t you just listen to the story?” one of my sisters said.]

“He ran over and picked the flower, and lo and behold, a thunderous voice boomed from behind the wall, as a man’s face appeared.

‘Who are you? How dare you pluck my only flower?’ the man said.

‘I… I… am so sorry. I saw this beautiful flower and could not help myself,’ the merchant replied in a terrified voice, for what came after the face was not a human body but a gigantic, coiling snake.

[“How big was the snake?”

“Very big—so big it could survey his whole house without moving at all.”

“How did it do that?”

“He sat in his living room and stuck parts of his body out so his head could move around the yard.”

“Wow, I wish I could do that—then I wouldn’t have to go to school!”

“You want to become a snake? Ugh!”]

“‘So, you thought that since the flower was pretty you could just pick it for yourself?’

‘No, sir, I… I…’

‘You what? If you don’t give me a good reason, I’m going to devour you, and believe me, I can do that very easily.’

[“If he had a knife with him, he could cut his way out of the snake’s belly and kill it too,” I said.

“Why do you have to interrupt all the time?” asked my second sister.]

“The frightened merchant told the snake about the promise he’d made to his daughter.

‘Hmm, you sound like a good father. I will spare your life if one of your daughters is willing to take your place,’ the snake said with an unfathomable glint in his eyes.

‘I’d rather be devoured by you than have you harm my daughters!’

‘I won’t eat your daughter—I just want her company. I live alone in this big house and I’m very lonely. No girl wants to marry me, because I’m a snake.’ The snake was looking quite sad.

[“Do snakes get lonely too?”

“How would I know? Go ask a snake.”]

“‘I don’t know about that. I don’t want my daughters to marry a snake either,’ the merchant said to himself, clearly not daring to reveal his thoughts.

‘It’s up to you. Either I swallow you or you give me your daughter.’

‘I have to talk to them,’ the merchant said meekly.

‘Sure, go talk to them. You’ll know which is the filial one—whichever one is willing to sacrifice her happiness for her father. Especially after you’ve bought them beautiful clothes and fancy jewelry.’ The snake smiled.

The merchant was speechless. How could the snake have known what he’d bought for his daughters? But saving his own life was a more pressing matter, so he hurried home.

‘Remember, I know where you live. So if one of your daughters doesn’t come on your behalf in three days, I’m going to look you up and devour you!’ the snake shouted at his retreating back before recoiling inside the mansion—a sight that the merchant was fortunate to miss.

[“How did the snake know everything?” I asked.

“He was a snake demon,” my mother said.

“Where does a snake demon come from?” I asked.

“If a snake tries to be good and study the Tao, it will gradually take on human form. This snake hadn’t being studying very long because only his head was like a human’s,” my mother said.

“What is Tao?” I continued.

“Tao is to become human. Don’t you know anything?” my second sister answered impatiently.

“How would I know? We don’t learn things like that at school.”]

“when he arrived home, the merchant gave the presents to his daughters, who received them with shrieks of delight. Except for the youngest one; she could tell that something was wrong and pressed her father persistently until he told them the truth behind the flower. The first two daughters said they wouldn’t go to live with the snake, since they were not the ones who had asked for the flower. The youngest, also the prettiest, said she would go.

[“Ha! Seventh can go live with the snake,” my second sister said.

“Seventh” was my nickname, for I was the seventh child.

“I don’t want to. I don’t want to live with a snake. Mom, please don’t let them make me go live with a snake.”

“They’re only teasing you.”

“Yes, Seventh can go.” It was my third sister.

“I’m not the prettiest one, so I don’t have to go. Second Sister will go; she’s prettier than me and Third Sister.”]

“The youngest daughter was terrified of the snake in the beginning, but he turned out to be a real gentleman who treated her tenderly. They were very happy together. And his house was filled with wonderful things.

[“What kind of wonderful things, Mom?” I asked.

“A big, nice Simmons? ”

“What’s a Simmons?”

“A bed with spring coils. It’s so soft, you sink into it as soon as you lie down.”

“Sixth, let Mom finish,” my second sister said.]

“After a year, the youngest daughter was no longer afraid, but she was very sad, because her father had passed away. Then, one day, her sisters came to visit her. They were completely taken by the riches of the mansion and could barely conceal their envy. So they offered to stick around to help the younger sister take care of the big house while plotting to kill her.

[“Don’t worry, Seventh, we won’t kill you...”

“Shush!”]

“They tricked her into coming to the edge of the well one day and pushed her in when she wasn’t paying attention. Then the oldest one put on her youngest sister’s clothes. when the snake came in from outside, he was puzzled by the changes.

‘Why do you look so different today, my dear?’

‘I… I fell and hurt myself.’

‘Where’s your other sister?’

‘She had to return to take care of the empty house.’

So the snake did not suspect anything. But later, when they sat down to eat, suddenly from outside flew a pretty little bird with a beautiful voice. The bird circled above the oldest sister’s head and sang:

‘Shame, shame, shame! Eat my food and wear my clothes! Shame, shame, shame on you!’

The two older sisters were afraid that their scheme would be exposed, so they quickly grabbed the bird and killed it. They then cooked the bird and shared its meat. But the second sister choked to death on a bone. Enraged, the remaining sister ate the rest of the bird and buried the bones she’d spat out in the yard.

The next morning, a bamboo grove shot up in the yard. whenever the wind blew over the towering green grove, the bamboo would sing:

‘Shame, shame, shame! Eat my food and wear my clothes! Shame, shame, shame on you!’

The sister was both angry and afraid at the same time, so she cut down the bamboo and made it into a chair. when the snake sat on it, nothing happened. But as soon as the sister sat on it, it collapsed, and she fell and died.”

There was always a momentary silence when my mother finished the story; then we all went to bed anxiously awaiting the next time she would retell the story. It was a story with a sad ending, because the youngest daughter died, so why did we want to hear it over and over again? Looking back now, I realize that it was not just because of the moral lesson that evildoers will be punished, but also because of the power of fairytales to transport us to a world of wonders.

Like the stories my mother told us, the wondrous tales collected in this volume have delighted generations of Chinese children, who have heard them from their parents, their grandparents, older siblings, or a particularly good storyteller. They could live in a spacious family compound in a big city or in a hovel at the edge of a remote village. There could be mosquito coils and palm fans, or perhaps air-conditioning and ice-cream to accompany the age-old tradition of whiling away a lazy summer evening with a story; the eager audience might be huddled around a fire or gathered on a heated brick bed on a cold winter night. These tales can serve to teach a moral lesson, like my mother’s The Gentleman Snake, or they may simply satisfy the needs of audiences and storytellers to let their imaginations run wild. we like them no matter what, as children and as adults, as listeners and—why not?—as storytellers ourselves.