Читать книгу Collecting Modern Japanese Prints - Norman Tolman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

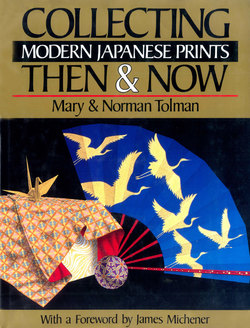

ОглавлениеForeword

by James A. Michener

One of the most rewarding adventures I've had in the world of art occurred when I was a correspondent in the Korean War. On frequent leaves for R & R, rest and recuperation, I scurried over to Japan, where I met an extraordinary young man. Oliver Statler, from a suburb of Chicago, had remained in Tokyo after World War II as a member of General Douglas MacArthur's Occupation team. With both skill and an aptitude for making friends among the Japanese, he accumulated the rich materials he would later use in writing his international bestseller Japanese Inn.

In the course of his researches, which reached back to 1945 when he landed in Japan along with MacArthur, Statler, who had wide experience in the arts, had become acquainted with a group of Japanese woodblock artists who were remaking the traditions of that ingratiating art form, the ukiyo-e print. Those prints dealt with the "floating" or underground world of geishas, samurais, and sumo wrestlers and was made famous by world-class artists like Masanobu, Harunobu, Kiyonaga, Utamaro, Sharaku, and especially Hokusai and Hiroshige. Their prints won worldwide approval, with major collections assembled in Paris, in London, and notably in Boston.

But the classic ukiyo-e print, of which I would collect some six thousand, had become typecast, offering mainly scenes of Japanese life, portraits of famous geishas, and landscapes of Mount Fuji. The younger artists of Statler's day longed to become not Japanese artists bound by the old cliches but artists in the worldwide sense, free to use any subject matter that inspired fellow artists in Paris, New York, or Vienna. They rejected the designation ukiyo-e artists, preferring the term hang a artists, and this handsome book portrays their art and the revolution they engineered.

Statler was so impressed with their work that by the time I reached him he had already assembled a huge collection of their best work, and in time he would have one of the world's best collections of the Modern Japanese print. He was so excited by his discoveries that he launched me on an exploration of the field, and this present volume reproduces work by some three dozen artists I collected at that time. Before long I became an aficionado, and even formed fast friendships with several of the artists and carvers whose work I admired.

In those exciting days, when each visit to Tokyo brought new discoveries, the field was dominated by four artists, three of whom are not represented in this publication because their work antedated the time period covered by this book. Hashiguchi Goyo had produced ravishingly beautiful portraits of women from everyday Japanese life, but he had little effect on the larger movement. Munakata Shiko composed wonderful designs in bold black and white, while Onchi Koshiro, with a European taste welded to a strong Japanese tradition, did captivating prints that could have been done by Klee, Miro, or Schwitters, had they been Japanese. He would exert a powerful force on the printmaking of his day.

The fourth dominant figure in this early postwar period was Saito Kiyoshi, who is handsomely represented here (plates 2, 58). Many American and European collectors started their gathering with two or three Saitos, and his works still command attention.

My affection goes to the work of two men I knew well. Azechi Umetaro (plate 14) was a rugged little fellow who excelled in mountaineering and whose prints reflected that obsession. Hiratsuka Un'ichi (plates 5, 76) was a handsome old man when I knew him as a family friend, and I marvel at his continued productivity as he nears the age of one hundred. I love his bold use of black and the effectiveness of his depiction of Japanese architecture.

Since this excellent book is divided into three parts— "Then," "Between Then and Now," "Now"—it is obvious that most of the artists whose work I knew well and collected will fall in the first segment, and seeing them again gladdens my heart. How bold are the two Sasajima Kiheis (plates 4,91), how delightful to see again an architectural print by Hashimoto Okiie (plate 6). I once bought several strong ones from him as we talked in his studio.

I break into laughter when I see Mori Yoshitoshi's three wild rickshaw pullers (plate 8), and Inagaki Tomoo's Long Tail Cat (plate 11) demonstrates how the artist can utilize traditional line to depict a radically new type of subject matter.

I recommend enthusiastically the final portion of the Tolmans' book, for it gives affectionate accounts of experiences the couple has had as collectors. Each story is different, each is instructive as to how amateur aficionados matured into sophisticated operators of a Modern-print gallery that often commissions specific artists to produce prints typical of their best work. This means that this book is in some ways an advertisement for the prints they have on sale, but this emphasis can be forgiven because of the very high quality of the work they sponsor.

Were I still on the scene and collecting—the collection my wife and I did make has been given to the Honolulu Academy of Arts—I am sure I would want to add the following prints: Iwami Reika's elegant Silver Waterfall (plate 27) because of its imaginative use of texture; Kinoshita Tomio's delightful Gray-Colored People (plate 51) because of its amazing sense of being an actual woodblock; Mori Yoshitoshi's warmhearted Tsukiji Fish Market (plate 50) because it recalls old-style works that featured many human beings; and Nakayama Tadashi's Running Horses (plate 44) because it represents the joyous freedom with which these newer artists work.

There remains one other print whose artist I had not heard of, and a special case he is. Clifton Karhu is an American of Finnish ancestry and is thus a prominent example of the recent phenomenon in which foreign artists have come to Japan to learn the business of making prints and have succeeded. But I would want this print (plate 52) for another reason. It depicts the kind of Japanese house with which I was familiar in the postwar days. In the inland town of Morioka, north of Tokyo, I lived in such a house during my earliest days in Japan, and seeing this print evokes a world of nostalgia.

I believe that anyone with a love of art and the mysterious miracles it can perform would find in postwar prints one or two examples of this exquisite art that would give her or him great pleasure and understanding. How about six that came to me as a complete surprise: plate 55 (Watanabe Sadao) because of its use of Western legend; plate 56 (Takahashi Hiromitsu) because of its use of very old Japanese legend; plate 59 (Sekino Jun'ichiro) because it exhibits the marvelous accuracy of Japanese carving; plate 60 (Maki Haku) because of its stark Japanese simplicity and design; plate 65 (Miyashita Tokio) because of its Klee-like exuberance; and plate 79 (Shinoda Toko), the mistress of the lot for two strong reasons: it was done by a woman artist, a rarity, and it bespeaks the soaring simplicity of much of the best postwar work.

Austin, Texas