Читать книгу Things Korean - O-Young Lee - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

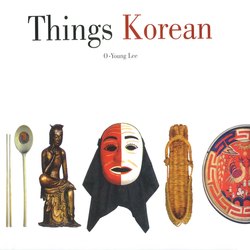

ОглавлениеForeword

The people of ancient times did not see the stars as scattered individual entities but as elements linked together in constellations. Heaven made the individual stars, but the mind of man made constellations out of these stars. And so the individual stars of heaven are the same stars, no matter where on earth we see them, but the peoples and nations of the world have given them different names and different stories. Where the Greeks saw Altair and Vega, for example, the Koreans saw Kyonu and Jiknyo.

If our ancestors made stories about these stars thousands of light years away, would they have ignored, as we do today, the utensils they lived so closely with in their everyday lives? In the tools and clothing and household items with which they lived for hundreds, thousands of years, it is unlikely that they would see, as we do today, no significance other than their utility.

The chopsticks they used for eating, the sashes they used to fasten their clothes, the ceiling rafters they gazed at as they reclined on the cool floor in the summer—all of these creations together formed a constellation in their minds. The nature of this constellation, in turn, reflected their mind. The things they lived with, more than being objects of simple utility, were the expression of what they saw in life and what they felt about life.

Is it just that the rays of stars come from so far away that the stars have now lost their luster? Is this why we in modern times are unable to hear what they are telling us? The things we use every day, too—even when we do regard one of them as more than a mere tool, it is because we see it not for what it is, but for what we can get from it. We regard it as a quaint or cute piece of handicraft, or we admire it for its value as an antique. We have lost the poetics of seeing the object as part of a constellation with many stories to tell, of seeing these objects together as a book with so much to tell us.

The book which you are holding in your hands now was born of the desire to conjure again those constellations. From this we want to form anew for ourselves an image of Korea, an understanding of the Korean mind, and to regain our sense of identity with our ancestors. The dabbler in folk arts and ways and the one who is looking for something to satisfy his interest in antiques will have no use for this book.

The one who may find something in this book is the one who knows the freedom and joy to be found in reflection on the nature of things, the one willing to devote the entire self to the adventure involved in deciphering that cryptic code which a culture builds from its objects to tell of itself, the one who has the eyes to distinguish, through the poetics of objects, the minds of Koreans in the images of the objects they use.

This book is not one man's work. The author deciphered the code in these objects; the editors compiled all this in their original approach.

As you will see when you thumb through these pages, this book itself is one object in that constellation. In this way it helps us understand the entire constellation. The unique Korean mulberry paper used in the original edition of this book has inherent in it something of what the book is trying to say. The Korean script used to write the original is not just the traces of words; each letter is itself a poetic symbol of graphics with independent existence, each having meaning in itself.

This book eschews the usual systematic order of beginning and end. Because each section is an entity in itself the reader is not required to begin on page one and proceed page by page through to the end. Each section is independent, so that you can begin reading wherever you open it. You might open at the end of the book, where you will find an appendix which offers more information on the topics in the main text. After finishing with the material in the appendix you can jump back to the main text, and then jump back again to the appendix at the end for further reference on another topic you may have come upon in the main text. This book can, then, be read in a continuous cycle. In a word, this is a format which has no beginning and no end.

We have often seen displayed in museums the earthenware crock, or a pair of shears, inherent parts of the Korean's everyday life. The crock, the shears, and every other item we see in the museum are individual symbols of an inclusive code which defines culture in one way. Through that thick glass, though, we can only look at these objects. We cannot stick out our hands and touch them. Those shears, alone there on the other side of that glass, can not cut even the softest fabric, just as we, on this side of the glass, cannot come close to scratching the surface of the cultural code which they hold inside.

This book, yet another star in the constellation of earthen crocks and shears—and kites and coins and all those other objects which fill our daily lives—is a decoded conversation with the co-inhabitants of its constellation.

Lee O-Young