Читать книгу Taduno's Song - Odafe Atogun - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOUR

The following morning they took a yellow taxi to the police station. The taxi had been recently repainted, and it wasn’t until they got into the back seat that they realised that the taxi was repainted to attract passengers. It looked very clean on the outside, but on the inside it was battered and smelled of damp.

It was too late for them to climb out by the time they discovered the ruse, so they made themselves as comfortable as possible on the torn leather seat which Taduno suspected was lice-infested. And as the taxi drove them to the police station, he filled Aroli in about his encounter the previous day with Sergeant Bello.

‘He could be the key to finding Lela,’ he concluded. ‘He knows something, but I doubt if he would want to share what he knows with us at the police station. He was not comfortable talking to me yesterday.’

‘What do you suggest?’

‘I suggest we meet him on neutral ground.’

‘Makes sense to me,’ Aroli agreed.

‘But we must be careful the way we approach him. Policemen can be very difficult people.’

‘I get you.’

They made the rest of the journey in silence.

Luck was on their side. They found Sergeant Bello alone in the office, dozing; a man with nothing meaningful to do, with no time for anything meaningful. The sound of approaching footsteps woke him out of his reverie, and he put on a smile and his worn beret, which he hurriedly picked up from his battered desk.

‘Good afternoon, Sarge,’ Taduno greeted. ‘Remember me?’

‘Ah, good afternoon! Of course, I remember you! How can I forget my friend?’ The Sergeant smiled expansively.

Taduno smiled back. ‘Friends are meant to remember friends, not forget them. I’m glad you remember me!’

For a moment the Sergeant’s face hardened. ‘Who’s this?’ he asked, pointing at Aroli.

‘Oh, this is my very good friend, Aroli. Together we want to help you to help us. You know it’s better for two to help one than for one to help one.’ Taduno laughed merrily to dispel the Sergeant’s fear.

‘I see what you mean!’ The Sergeant laughed too.

Aroli joined in the laughter. And together they all laughed merrily, like three idiots.

‘So?’ Sergeant Bello asked, when their laughter had died down.

‘Yeah, we’re thinking . . . we’re thinking you should have dinner with us tonight somewhere nice.’

‘Oh no, no, no!’ Sergeant Bello shook his head. ‘Dinner sounds okay to me, but not anywhere nice. I’m not used to nice. Nice is a mere waste of money.’

‘In that case we could go somewhere not so nice and not so bad.’ Taduno demonstrated with his hands, that smile of an idiot still on his face. ‘How about that?’

Sergeant Bello nodded with satisfaction. ‘That sounds better. I’ll be off duty by six. Just remember, nowhere nice. I don’t like nice. I don’t like nice at all!’

The three of them laughed loudly. And as Taduno and Aroli made to leave, Sergeant Bello stretched out his hand. ‘You are forgetting something,’ he said, in a frosty voice.

Taduno slipped a 500-naira note into his hand.

The Sergeant kept his hand outstretched. ‘“It’s better for two to help one.” Those were your words.’

Taduno shrugged and added another 500-naira note.

*

Their rendezvous was an open-air restaurant situated along a canal that carried half the city’s dirt. The restaurant was poorly lit, and it was certainly not nice, but not so bad by Sergeant Bello’s standard.

Their orders arrived promptly, and they ate quietly – Taduno and Aroli with relaxed looks on their faces; Sergeant Bello with a sombre look on his.

Under the poor light, Taduno had the opportunity to study Sergeant Bello away from the police station. And he was surprised to see the face of the city – a city battered by a regime that used hopeless people like Bello to perpetuate itself.

They finished eating and moved to an open-air bar, still along the canal, where people were drinking and murmuring, drinking and murmuring against the government, and their anger kept rising with their drunkenness. And their voices became so loud nothing they said made sense any more. And all that filled the air in that garden of drinking people was bitter anger against the government. And Sergeant Bello could take it no more – knowing he was against the people, and on the side of evil. And he felt sad knowing that the same people he was against murmur not for their own good, but for his as well.

Taduno sensed Sergeant Bello’s state of mind. He cleared his throat. ‘When the people murmur like this, it means there is hope for the future,’ he said, trying to sound cheerful.

‘Maybe. But what hope is there for someone like me?’ Sergeant Bello was forlorn. He drank some beer.

‘The same hope there is for us all,’ Aroli explained. ‘The same hope we share as a society.’

Sergeant Bello gave a small bitter laugh. ‘How can I share the same hope with these people when I’m a part of what they murmur against?’

‘Regardless of which side we are on, hope is universal. When you begin to hope, you begin to murmur against that which hinders you. And when you murmur, change is bound to come.’ Aroli shook his head. ‘I wish I could explain it better.’

‘You’ve explained it well enough.’ There was a distant look on Sergeant Bello’s face. ‘I have enough education to understand your words. And you know what?’

‘What?’ Taduno and Aroli asked as one.

‘I’m beginning to think there’s hope for me after all.’ A weak smile spread across the Sergeant’s face.

Taduno and Aroli exchanged looks.

‘Why did you suggest dinner?’ Sergeant Bello asked.

Taduno went to the point. ‘I need more information about Lela. Why was she kidnapped?’

Sergeant Bello looked thoughtful.

‘Why was she kidnapped?’ Taduno persisted.

‘Government is looking for her boyfriend. He is a musician who used his music to cause trouble for government. They can’t find her boyfriend, so they kidnapped her – as a ransom.’

‘So it’s her boyfriend the government is really after?’

‘Yes. If they find him and get him to sing favourably about government, she will be released. Otherwise, she will be killed. They are afraid that his music could start a revolution and topple the government.’

‘But she is innocent.’

Sergeant Bello laughed quietly.

‘Government does not believe in innocence.’

They drank in silence for a while. And then Taduno asked: ‘What’s the name of the man the government is looking for?’

‘They don’t know his name, and the girl would not tell. They only know him as a great musician with a magnetic voice.’

‘Have they got a picture of this man?’

‘No, they don’t. They used to know his name; they used to have his picture. But then something happened, something strange nobody can remember, and he became a man with no name and no face. They think he is at the heart of a sinister conspiracy to topple the government.’

‘So the government is looking for a man they don’t know, a man with no name and no face?’ Taduno wore a bewildered look.

‘Yes, but the girl Lela knows, and they are trying to make her reveal his identity.’

‘And the boyfriend must become a praise-singer for the government if they are to release her?’

‘Yes.’

‘Where are they holding her?’

‘CID headquarters. But I don’t advise you to go there! You’ll only get yourselves arrested and tortured.’

‘By the way,’ Aroli spoke slowly, ‘how would the government identify the man they are looking for if he has no name and no face?’

‘By his voice,’ Sergeant Bello replied. ‘His voice is his identity. He has the most wonderful voice in the world. No other human being sings like him . . .’

A slight pause.

‘Look, by telling you all these things, I’m simply joining my voice to those of the people, hoping that my little contribution will make a difference.’ The Sergeant shifted uncomfortably in his seat. ‘As I said before, government does not believe in innocence. If they ever get to know all that I have told you, my life would be worth nothing. So as far as I’m concerned, I never met you two and I don’t know you as friends of Lela’s.’

They finished their beer. Taduno settled the bill. And they stood up to go. To both Taduno and Aroli’s surprise, Sergeant Bello refused to take money in exchange for the information he had given them. ‘Take it as my contribution to the murmurings of the people,’ he said.

*

It was easy for Taduno to tell Aroli his story after that.

‘I used to live a simple life at first. I used to be a musician and all I sang was love songs – songs that encouraged people to live as one, to love without asking for love in return, to give without thinking of receiving,’ he explained, pacing the small living room of Aroli’s apartment.

It was his first time in the apartment since returning from exile, and everything was just the way he used to know it. The fake Mona Lisa still hung on the wall above the Sony television. The sofas were still the same, the ceiling fan still had the same hum, and the walls of the living room were still as bright as ever – a bright yellow that always reminded him of a nursery.

He continued.

‘And then everything changed, and I began to sing against injustice and oppression. Everything changed when the June 12th presidential election was annulled and the legitimate winner was thrown in jail. Through my music I became a force, a fierce enemy of the government.’

‘But your name’s not on the wanted list published by the government some time ago,’ Aroli interrupted.

‘That’s because you all forgot me – my family, friends, neighbours, the government – the entire country forgot me.’

A short silence.

‘So you started using your music to attack government,’ Aroli prodded, eager for him to continue his story.

Taduno stopped pacing and dropped into a chair.

‘Yes, I became an activist, a thorn in the flesh of government. The President’s soldiers beat me up on many occasions, sometimes leaving me for dead. They burned my car and closed my bank accounts. I remained unyielding. On many occasions the President tried to persuade me to give up, promising to make me very rich. But I turned him down, and I continued to fight him with my music. And then his soldiers threatened to kill me.’

‘So you went into exile?’

‘No, I continued to be a very vocal critic of the regime through my songs. Then they murdered the winner of the June 12th election in detention. The whole country erupted; the regime used the army and the police to subdue the protests. I realised that it was possible to depose the regime with music, so I continued to fight them with my songs.

‘And then they banned all record shops from selling my music. The army invaded the shops and confiscated all my records. They invaded my house, any house where my records could be found, and they seized every copy of my records. And they burned them all so that not a single copy of any of my records can be found anywhere today. I guess that was when every record of me was erased from all your memories. I no longer existed because there was no way I could continue to exist without my music. My music was me, and they took it away from me. That was when I gave up the struggle and went into exile.’ A deep sigh escaped him.

‘Yes, I know it now. The government took my identity away from me and destroyed it. They mutilated me and turned everyone against me – my family, my friends, my neighbours, the entire country. They ground me into the dust. And now even they can no longer recognise me because they destroyed every bit of me.’

‘What happened to your band members?’

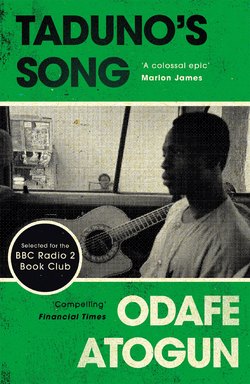

‘I didn’t need a band for my kind of music. My music compares to storytelling – it is best sung by one person. Two people cannot weave an enchanting story. I told stories with my music and the only musical instrument I used was the guitar. I had over thirty guitars. The President’s soldiers destroyed them all. I was to discover later that the many beatings I received affected my vocal cords. My voice has never been the same.’

‘So you are actually the man the government is looking for, Lela’s boyfriend,’ Aroli spoke, thoughtfully.

‘Yes, and I must convince the government that I’m their man if they are to release her. Sadly, nobody remembers me and I no longer have the voice to prove I am the musician they are looking for.’

He dropped his head in dismay, remaining like that for several minutes. And then he looked up with a glimmer of hope in his eyes. ‘I think I should just turn myself in and tell them I’m Lela’s boyfriend.’

‘No,’ Aroli said, shaking his head. ‘As you have said, nobody remembers you. Without your voice government will only see you as an imposter, and that could get you into serious trouble.’

Taduno saw Aroli’s point and nodded.

They talked a bit more without agreeing on what to do. The street was asleep when he left Aroli’s place. He went straight to bed. For a long time he lay fidgeting in the darkness, thinking of Lela and of himself, and he wondered what would happen to both of them if, in the end, nobody remembered him.